It’s Seventh Day of Myth-mas, and Si Spurrier continues his look at his favorite myths and monsters from across the world, many of which will be found in his new series from Image Comics in January, Cry Havoc.

Click links for previous Days of Myth-mas:

On the First Day of Myth-mas, Si Spurrier gave to us… THE ZOMBIE.

On the Second Day of Myth-mas, Si Spurrier gave to us … THE HORRIFYING PENANGGALAN.

On the Third Day of Myth-mas, Si Spurrier gave to us … THE SLEIPNIR.

On the Fourth Day of Myth-mas, Si Spurrier gave to us … THE LITTLE PEOPLE.

On the Fifth Day of Myth-mas, Si Spurrier gave to us … THE YARA-MA-YHA-WHO.

On the Sixth Day of Myth-mas, Si Spurrier gave to us … THE BLACK HOUND.

—

Now, on the Seventh Day of Myth-mas, Si Spurrier gives to us … THE ANGELS OF MONS…

By SI SPURRIER

A lovely little example now of the untameability of folklore, and the capacity for a good story to blow raspberries at trivial obstacles like, oh, Being Demonstrably Fake.

In August 1914 the British Expeditionary Force undertook its first serious encounter with the German foe of the Great War (or “WWI”, for those of you don’t realise the extent of the Napoleonic wars a century earlier). At Mons the Brits, horribly outnumbered, managed to push back the German advance – briefly, and at great cost – before hurriedly withdrawing the next day.

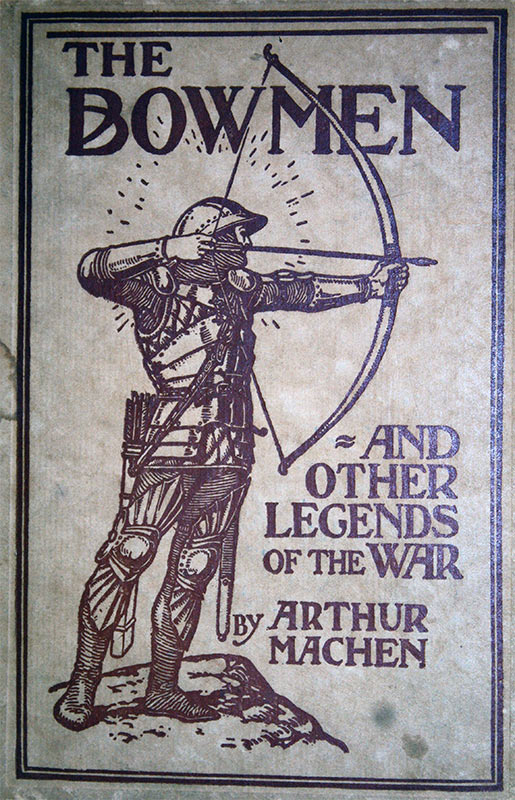

A month later a short story appeared in The Evening News, which made no claims whatsoever to be factual, written by Arthur Machen. Yes, the same Arthur Machen I mentioned back on Day 4: an absolutely bloody wonderful writer, spiritualist and all-round great guy, whose star has been unforgivably eclipsed by numberless inferior wordists who came later, and who pretty openly nicked his ideas, his style and his tone. *cough* Lovecraft *cough*

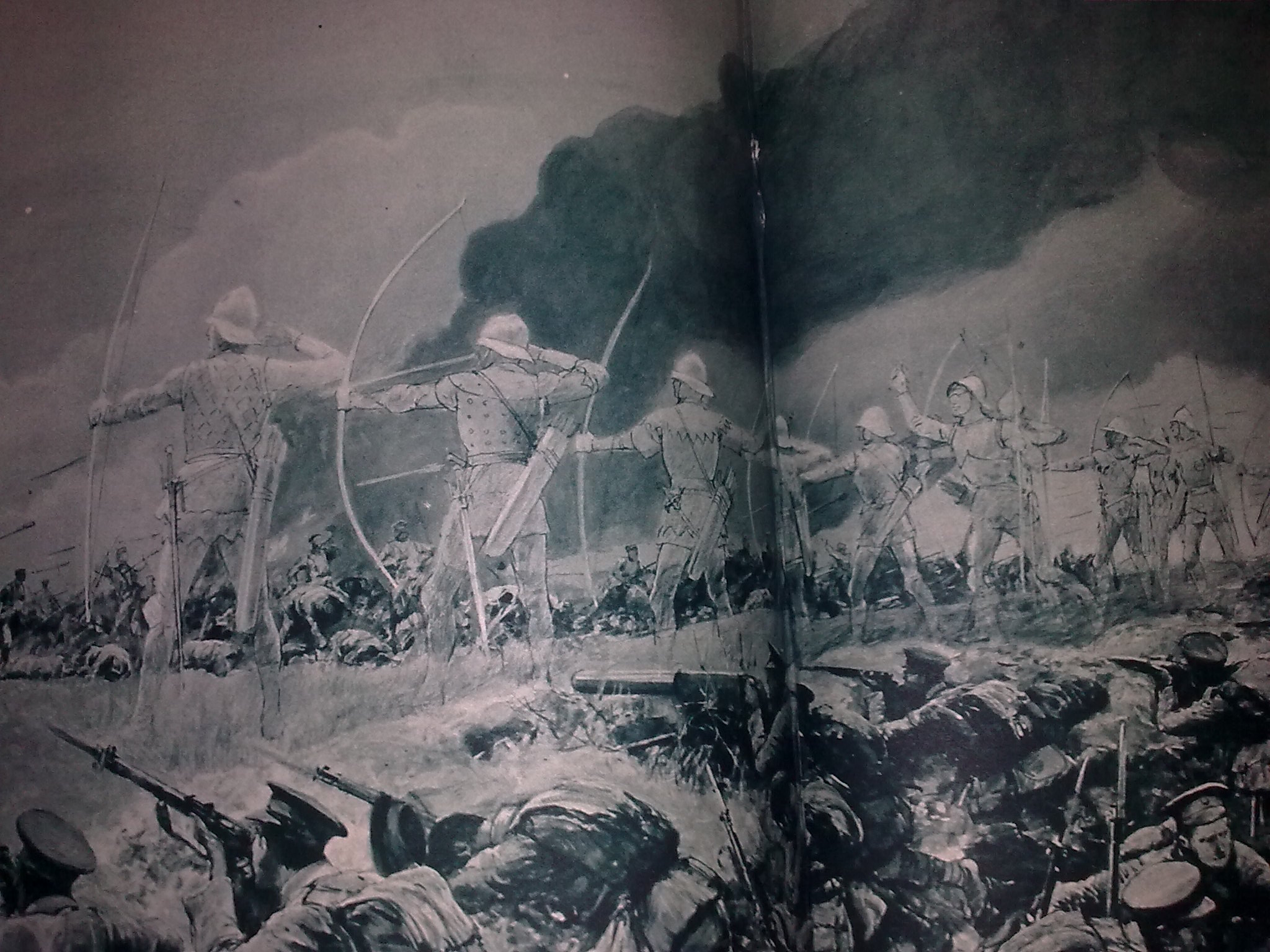

Anyway, Machen’s short story, The Bowmen, was a grim and gritty little tale about the battle of Mons, during which one despairing Englishman cries out to Saint George for deliverance. Whereupon a horde of shimmering, ghostly bowmen, understood to be the spirits of the English archers who died at Agincourt, appears in the midst of the battlefield and sends the German troops packing. Short, sweet, silly, patriotic fun. Machen thought it was one of his worst stories.

But within two months he was getting earnest requests from church organisations and parish magazines all over the country to reprint the tale. It quickly became clear priests were presenting the account to their congregations as fact: cold, unbiased reportage of a true miracle. Machen tried his best to stem the tide, insisting again and again that he’d invented the whole thing, but found to his horror that people believed so fervently (or, perhaps, wanted to believe so fervently) that they either begged him to stick to his guns, or simply dismissed his retractions as lies.

Within a year the story had spread across Britain and Europe, mutating as it went, to the extent that the “shining bowmen” had become a horde of luminous angels, demonstrating once and for all that God was on the allies’ side.

In the end poor old Machen – who gives himself a really hard time about all this in his biographies, and flatly states that he’d not only failed in the art of fiction but had accidentally succeeded in the art of deceit – realised that the propaganda-value inherent in the gossip was so great that any attempt to turn back the tide would be regarded as treason. He spent the rest of his life bitterly ashamed of the whole business, and gave as his final word on the subject this beautifully distilled nugget of wisdom on the nature of myth:

“No tale is too idle to be believed.”

—

NEXT: THE KAPPA.