INSIDE LOOK: An interview with the screenwriter…

—

UPDATED 2/17/21: With the Batman ’89 comic coming in July from DC — click here for all the details — it seemed like the perfect time to re-present this piece from 2019. Dig it. — Dan

—

Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman movie is celebrating its 30th anniversary in June — and we’ve got some nifty coverage planned for you. More on that soon.

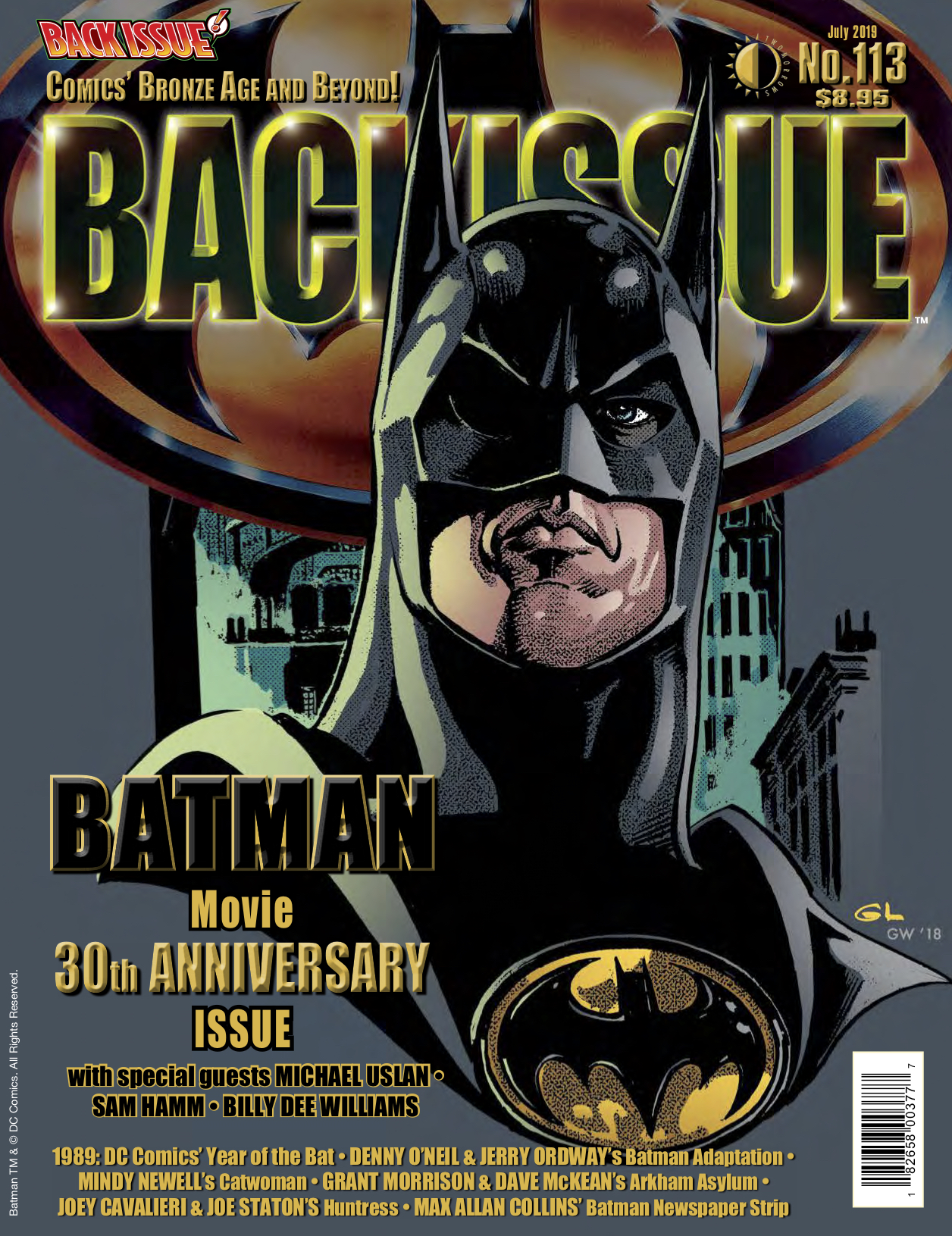

Meanwhile, Back Issue magazine is getting a jump start of the festivities – dedicating Issue #113 to the seminal flick. The issue was originally scheduled to be in comics shops May 29, but it made it out there early, so make sure you get your hands on it. It’s must reading.

Just dig the table of contents:

Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez

Man, so much great stuff in there.

In any event, below is our regular Back Issue EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT — in this case an entertaining segment from Michael Kronenberg’s interview with screenwriter Sam Hamm. They cover a lot of ground, but we’re zeroing in on what Hamm had to say about the comics that inspired his work.

As you’ll see, Hamm’s Bat-background is more colorful and varied than you might think. Let’s drop in to where he began discussing his vision with Burton…

—

By MICHAEL KRONENBERG

Sam Hamm: (Tim) asked me: “Would you have any interest in working on this Batman thing?”

“Sure,” I said, as nonchalantly as I could. I didn’t mention that I had spent the last six months crawling on my belly like a reptile to get the job. And as soon as we started talking about Batman, I could see we were going to get along. “The weird thing about Bruce Wayne is he’s this incredibly rich guy, but all he wants to do is put on a suit and beat up petty crooks,” Tim said. “Why is that?”

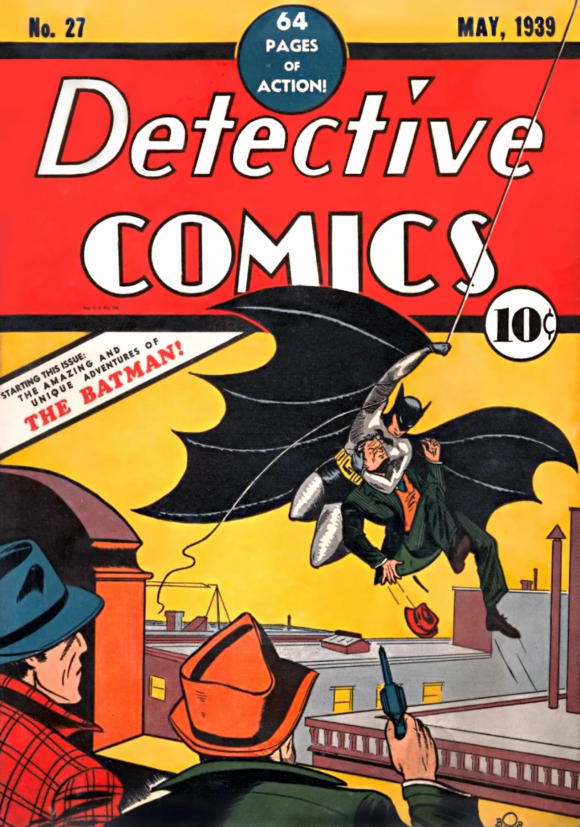

“That’s the picture,” I said. “That’s the mystery.” You don’t start with Batman’s origin. You start with the Joker’s origin. Batman is a mysterious vigilante: a shadow, a monster, a rumor. He may or may not exist, but he has the Gotham underworld in a panic. Which happens to be exactly the way he was introduced in Detective Comics #27.

Bob Kane

By the time I finally left the lot that day, we had our basic character arc worked out. Batman is a guy who has made an extremely questionable career choice. What happens if he starts to go… sane?

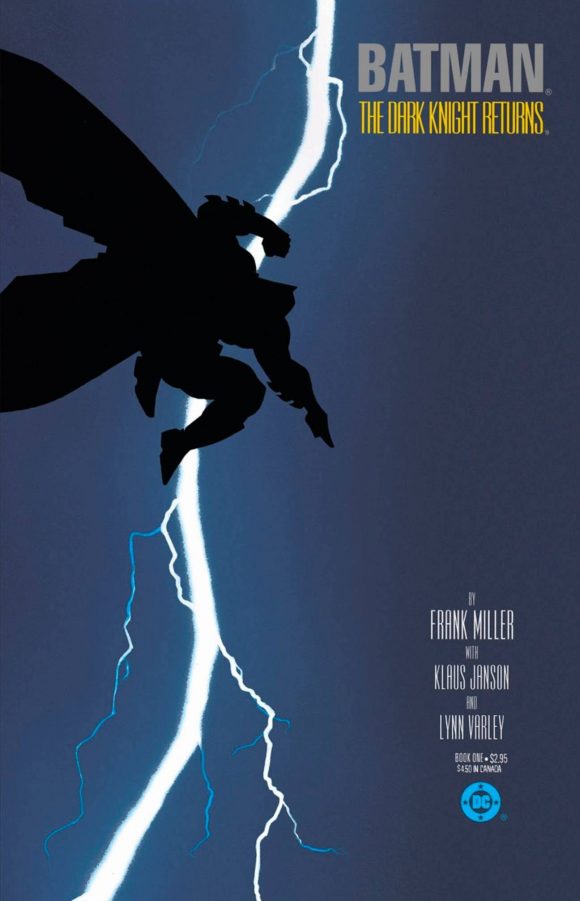

Michael Kronenberg: In 1988, even though Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns had been released and made an impact, there was great concern among comic-book fans that a potential Batman movie would be close to the TV series in tone. Your script was quite dark. Was this something you alone decided or did the producers also want a darker Batman?

Hamm: As a kid, I was a religious viewer of the Batman TV series. Like the other kids in my neighborhood (average age: nine), I had no problem taking it seriously. I remember widespread consternation among my peers when the show was nominated for an Emmy as “Best Comedy.” Batman? Comedy?!? All the magazines referred to the show as high camp, but we were not up to speed on our [camp essayist Susan] Sontag. We had no idea what they meant.

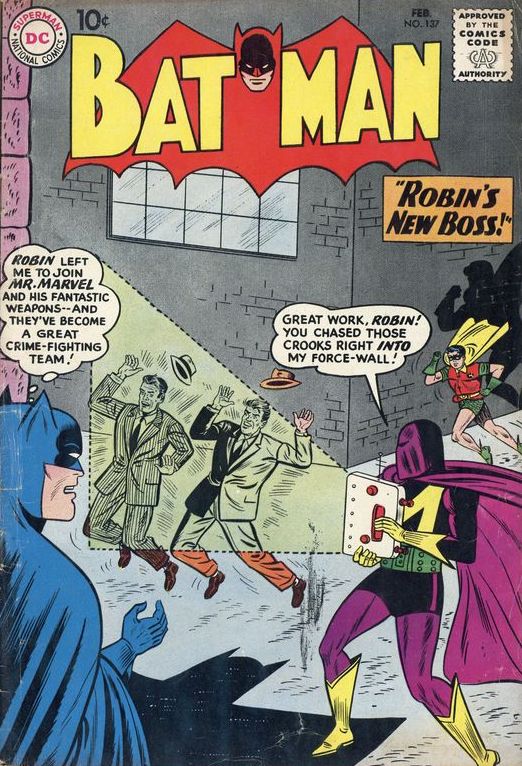

Of course, the show was downright dignified compared to the comics of the late ’50s and early ’60s. The first comic book I ever owned was a Mighty Mouse my uncle bought me when I was three, and the Batman stories I began reading a year or so later may have been a little “darker” than Mighty Mouse, but not by much. This, remember, was the era of Batwoman, Bat-Girl, Bat-Mite, and Ace the Bat-Hound. Typical plots? Bat-Girl steals Batman’s thunder, or Robin ditches Batman to team up with the ominously named “Mr. Marvel.”

Sheldon Moldoff

There were aliens and monsters everywhere. And weird transformations! In Batman #158, Ace becomes “The Super Bat-Hound!” (“Great Scott! Bat-Hound has acquired super-powers, and he’s using them against us!”), a mere eight months after Robin became “Robin, the Super Boy Wonder!” in Batman #150, with similar results. Batman himself metamorphoses into “The Bizarre Batman Genie!” [Detective #322] and “The Colossus of Gotham City!” [Detective #292] prior to the final indignity, which comes in “The Story of the Year!” from Batman #147: “Batman Becomes Bat-Baby!” And yes, in case you are wondering, he continues to terrorize the underworld—as a toddler.

In ’64, [editor] Julius Schwartz and [artist] Carmine Infantino took over the Batman titles and—largely, I imagine, as a reaction to what was happening over at Marvel— smartened them up considerably. But till then? Shit. Was. Ludicrous. Looking back, I have a sneaking hunch that hardcore Batfans have always resented the TV show not because it lampooned the comics, but because it captured their inanity so accurately.

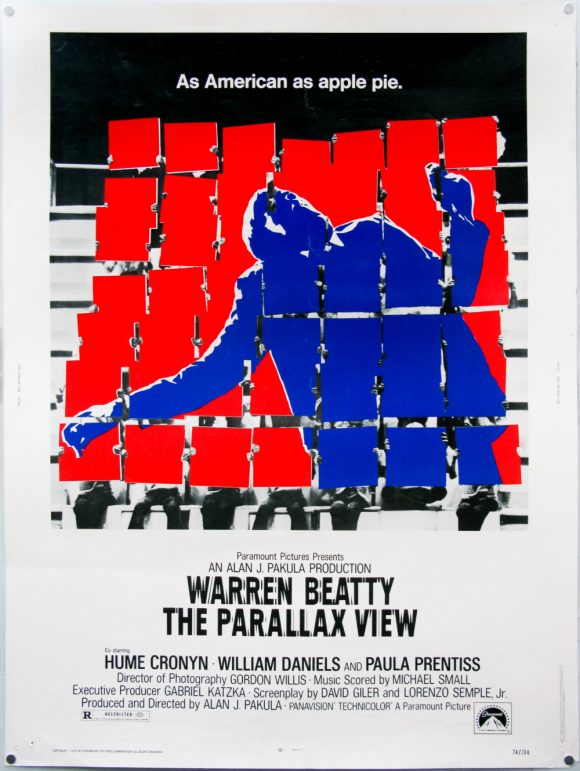

But I loved the series just as I loved those dumbass comics. I still love the late Lorenzo Semple, Jr., who (helped) create the series and who went on to write a handful of terrific screenplays, including Pretty Poison and The Parallax View. His “take” on Batman proved equally satisfying, albeit in different ways, to both kids and adults, and the result was a huge media phenomenon. He caught the Zeitgeist.

So: Getting back to your question, Tim and I had not been given any special instructions re darkness of tone. It evolved naturally. The comic- book Batman had been really cool when I was five; the TV Batman had been really cool when I was ten. Now I was 30 and Tim was almost 30, and the task we set ourselves was to figure out a version of Batman that would still be just as cool to us, as adults. That meant we had to take the character seriously. We had to imagine what it would be like to be a masked vigilante out in the real world. We thought it would be hard. We thought it would be dangerous. We thought it would mess up your social life. We wanted big stakes, and we wanted a genuinely nasty villain: no eccentric ninnies plotting thematically related bird crimes, or sending out riddles that would make them easier to catch.

When the script came in, the studio was very happy with the direction we had taken. Just before production started, there was a little front-office trepidation over the fact that our movie might be too violent for six-year-olds, or worse yet, their impressionable parents. But in the end, the studio gambled—wisely, as it turned out— that 12-and-overs would make up the difference.

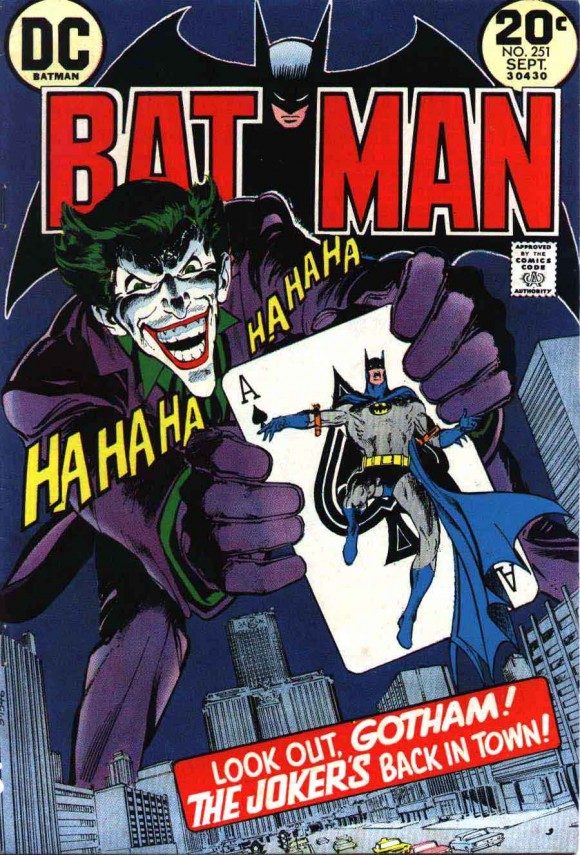

Neal Adams

Kronenberg: What kind of and how much research did you do before you wrote the script?

Hamm: I have a crusty B&W snapshot of myself at age four, in a cowboy hat, reading a copy of Batman #133, with “Batwoman’s Publicity Agent” on the cover. (Guest-stars: Bat-Mite, Ace the Bat-Hound.) I guess you could say that photo was taken in the early stages of my research.

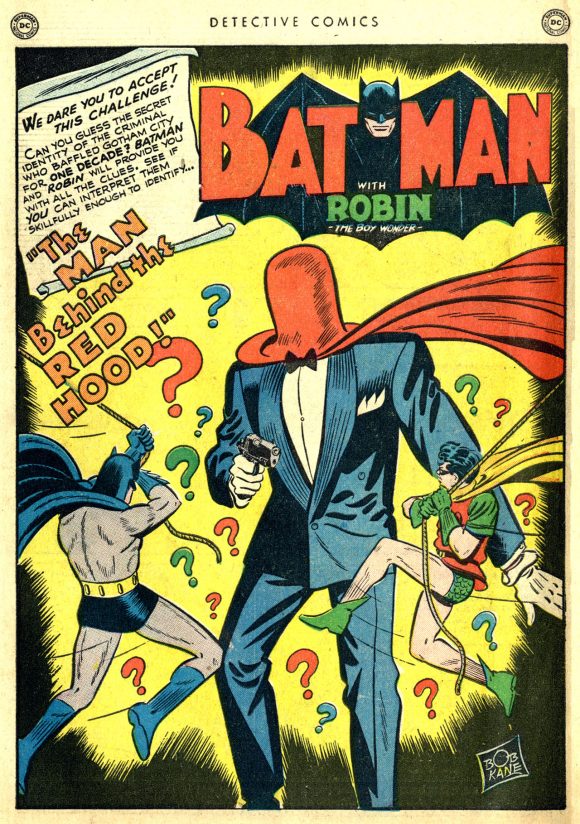

But seriously, folks: I’m pretty sure I reread the Joker origin story, “The Man Behind the Red Hood,” from the early ’50s [Detective Comics #168, Feb. 1951]. And I reread “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge” [Batman #251, Sept. 1973] by Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams, which is generally considered to be the story that reinvented the Joker as an unpredictable psychopath, a “wild card,” as opposed to a clown. Mostly I was drawing on happy, vivid memories from my squandered youth.

Splash from Detective Comics #168. Written by Bill Finger. Pencils by Lew Sayre Schwartz (except Robin by Win Mortimer). Inks by George Roussos.

Kronenberg: While reading your script, it seems that Batman #1, the Detective Comics run by Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers, Miller’s Dark Knight, and a little of Batman: Year One had some influence on you, primarily the integration of the Joker telecasting on TV, the symbol of Martha Wayne’s pearls, Batman on horseback, and Batman’s use of bats.

Hamm: Dark Knight was, I think, two issues in (or halfway through) when we started work, but [DC Comics’ then-publisher] Jenette Kahn and the nice folks at DC sent us B&W Xeroxes of the upcoming issues. I had gotten independently geeked up about [Dark Knight] thanks to a Rolling Stone article that had described the central conflict as a left-wing Batman versus a right-wing Superman, but, of course, the series ends disappointingly with Batman as a benevolent fascist. Still, there was a lot of beautiful stuff we wanted to appropriate, such as the visual of Batman on horseback (in the Robin intro I wrote that eventually got cut) and the notion that the Bat-insignia on our hero’s chest is a target designed to draw gunfire away from his head.

Frank Miller

DC also sent us the Englehart/Rogers run of Detective, which they were quite taken with, but I don’t think we borrowed much from it beyond the notion that Gotham City was run by the mob. Batman’s “use of bats” came about because with my impeccable logic I figured that, if the hero was named Batman, the climactic action sequence should take place in a belfry. As I wrote it, Batman has in essence decided that he will commit suicide if that’s what it takes to stop the Joker. His totemic winged mammal shows him a different way out of the jam.

Year One, which is, to my mind, one of the best comics ever, did not appear until we were a few drafts in, so we did not have much opportunity to pinch from it.

—

Back Issue #113 is on sale now. You can get it from your local comics shop or directly from TwoMorrows. Click here.

—

MORE

— 13 Things I Still Love About BATMAN ’89. Click here.

— Jack Nicholson’s 13 Best JOKER Quotes — RANKED. Click here.

May 25, 2019

Happy 30th anniversary to Tim Burton’s “Batman”!

June 8, 2019

Dokładnie TAK !