Josh Hicks — writer and artist of the new tokusatsu satire Hotelitor — waxes rhapsodic about rubbery monsters and robots that beat on each other…

By JOSH HICKS

Some of my earliest memories have to do with an action figure. Here in the UK, the summer of 1995 saw each box of Kellogg’s Frosties packaged with a tiny plastic Power Ranger – the result of a temporary cross-promotional alliance intended to sell cereal and advertise the Rangers’ upcoming movie. When my family opened up our box of Frosties, it was the White Ranger who fell out.

Not Josh’s

The term ‘action figure’ is stretching it. He was a few centimetres of solid plastic, permanently posed with hands on his hips – an expression of heroism or disapproval, depending on the light. I took him everywhere. The only way my parents could get me to school was to let me take the White Ranger with me. I wanted to sit at home, watching him and his friends fight evil on TV, while I played out a world of imagined further adventures on the living room floor. In the strange new world of the classroom, the only further adventures I imagined were ones in which I was back home. This little White Ranger basically represented the sum total of my five-year-old passions and interests, condensed down into a few grams of plastic and paint for easy transport in a lunchbox. There’s also a ton of VHS footage of me running around family gatherings in a full Power Ranger outfit, but luckily this getup never made it to the schoolyard.

My heroes gang up on a plant.

At the time, I had no idea that Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers was an American repackaging of Japan’s Kyōryū Sentai Zyuranger, with the Fox Kids show marking another step in the long and storied history of the Western repurposing of Japanese tokusatsu media. Translated literally as “special photography,” tokusatsu is a strain of specifically Japanese live-action film and television that prizes practical special effects. Export and cultural exchange has been a key part of tokusatsu media since its golden age in the 1960s and ’70s: toku pioneers Ultraman and Giant Robo made their way to American TV screens via crude dubs, while British national treasure Thunderbirds became a hit in Japan, partly owing, I imagine, to its own, puppet-themed brand of wirework, scale models and commitment to blowing things up.

Ultraman and Giant Robo (Johnny Sokko and his Giant Robot in the US)

It wasn’t til the ’90s, however, that the process of toku Westernisation was perfected for Saturday morning TV. Instead of a straight dub, Power Rangers took a similar approach to the American localisation of 1954’s Godzilla, with new scenes being shot with American actors to fit around imported Japanese action footage. When Power Rangers was a hit, a rehash of the formula with other Super Sentai shows followed, as did a bunch of copycat shows based on other tokusatsu properties. These Westernised shows are almost all reviled by purists in the cold light of 2024, but I was there for all of them the minute they hit Welsh shores.

Why did all this stuff hold such allure? Sure, some of it has to do with the basic, superhero setup of it all – teens with masked identities, monstrous villains, at least one big punch-up every episode – and on the surface, these shows were similar to the American comics and cartoons I also loved. But even without any inkling of their geographical origins, the specific brand of joy these shows offered felt different. With their focus on practical effects (again: scale miniatures, in-camera explosions, wilful ignorance of health & safety protocol) and often-unhinged rubber monster designs, the tokusatsu shows oozed creativity. A sense of handicraft permeated every frame. Giant robots, polystyrene cities… these were real things that real artists built, tangible objects that you felt you could touch – just like the plethora of licensed toys I feverishly hoarded. Somewhere, there were people – adults – whose job it was to imagine this stuff, the more bizarre or outlandish the better, and then painstakingly bring it into the realm of the real.

Men dressed as robots prepare to do battle; my childhood heart skips a beat.

Tokusatsu’s influence on American mass media in the ’90s didn’t stop at these retrofitted imports. The aforementioned Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: The Movie was produced entirely in the West, as was Roland Emmerich’s New York-set 1998 Godzilla. It’s probably no coincidence that both these productions largely eschewed the charming suitmation and ambitious in-camera effects of their Japanese counterparts in favour of high-budget CGI sequences that have, at this point, aged like a latex monster suit left out in the rain. Emmerich’s Godzilla especially is a practically joyless rewatch, but at the time this didn’t matter to a child without the function for critical analysis: I loved it all the same.

I aged up and left my Power Rangers and Godzilla figures behind at some point, but tokusatsu would continue to bleed into my childhood and adolescence, in ways both clear and opaque. Finished with Cartoon Network’s airings of Dragon Ball Z and Gundam Wing and looking for something stronger? VHS tapes of the Ultraman-influenced Neon Genesis Evangelion are the perfect find for any 13-year-old in need of gentle psychological scarring and a complete rewriting of their understanding of reality. Dipping your toes into midnight movies? Your local Blockbuster has a spotty collection of Godzilla movies dating back to the ’60s, as well as adult-focused modern stuff like your Cassherns or your Machine Gun Girls or your Cutie Honeys. Gripped by a compulsive teenage need to make movies with your friends and don’t know where to shoot? There’s a giant abandoned ditch near your house, and you’re suddenly struck by the ancient, long-forgotten knowledge that hills and dirt equal the perfect setting for any action sequence, whether it makes sense to the plot or not. Thanks, tokusatsu.

Ultraseven. Definitive proof that tokusatsu is high art.

When the pandemic hit, I found myself watching entire seasons of Ultraman and Ultraseven online, and not really knowing why. In hindsight, part of it was escapism. Part of it, I’m sure, was nostalgia for the shows’ 1990s equivalents. Part of it, though, was just the opportunity to revel in pure creativity – the behind-the-camera subtext of every single episode being that real people got together, aimed beyond their means and often risked third-degree burns to bring this all to our screens. In my idealised fantasy version of ’60s tokusatsu working conditions – encouraged by behind-the-scenes hagiographies like 1989’s made-for-TV movie The Men Who Made Ultraman – these creators were a tight-knit team, working shoulder-to-shoulder to make magic. Something about basking in the fruits of their combined labours felt especially soothing amid worldwide isolation.

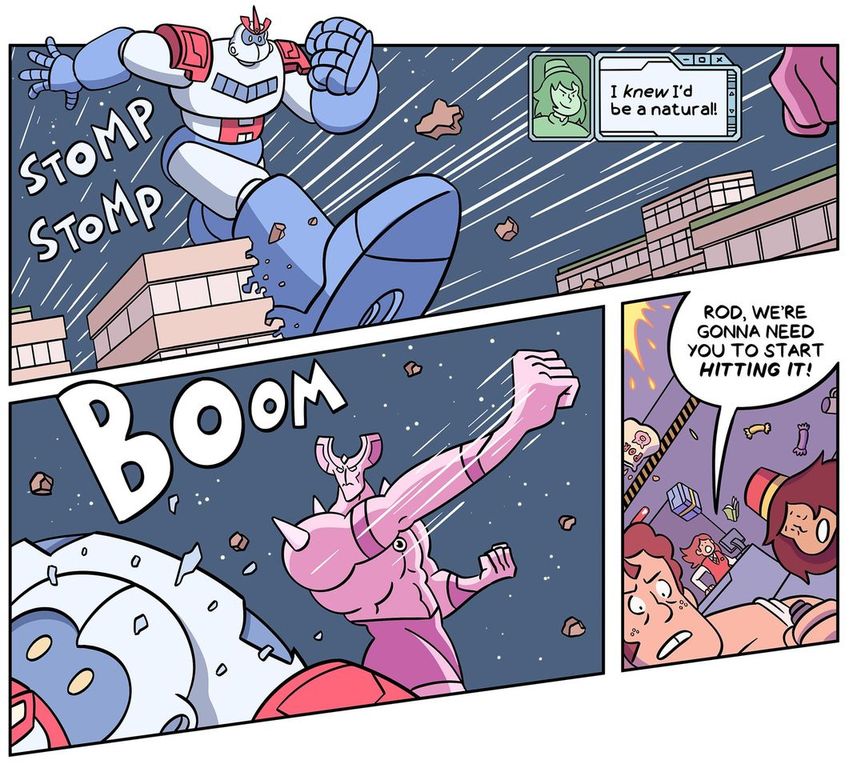

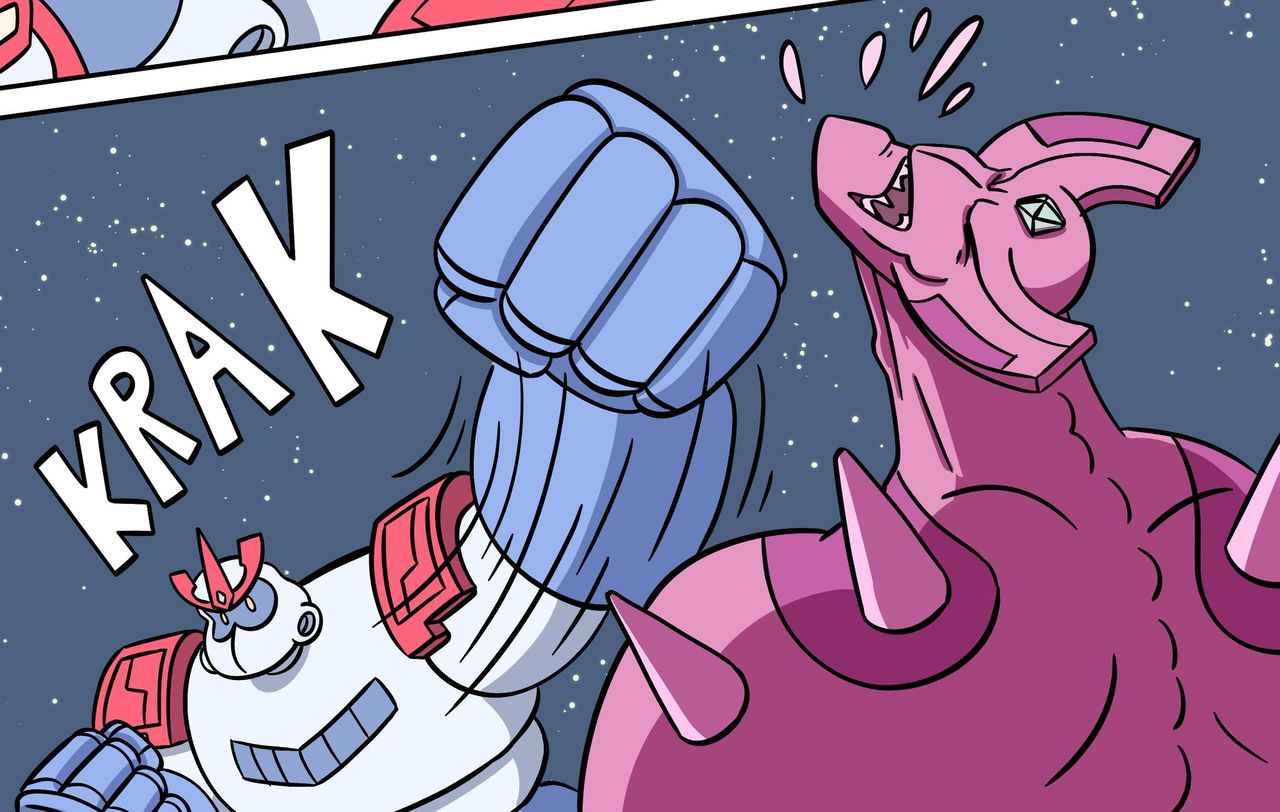

It was around this time that I started work on my latest comic, Hotelitor. It’s a comedy that deals with work and capitalism– as well as being about a giant robot that is also a hotel – and through some unexplainable internal logic, tokusatsu felt like the logical convergence point of those disparate strands. There’s also the chance I was just watching way too much of this stuff when I wrote it. I wanted to steer clear of the troubling exoticism that can infuse Western art born from Eastern points of influence, with my main tokusatsu takeaway being the one-hundred-percent commitment to the bit: a silly idea taken to its logical endpoint through sheer time, energy and effort – three things drawing a graphic novel requires in spades. My medium, luckily, did not require me to handle explosives.

The giant robot fight I’ve waited my whole life to draw.

If I had slightly more in the way of delusions of grandeur, I’d possibly reckon Hotelitor to be a small part of some odd new wave of Western tokusatsu-inspired art that’s cropped up in the last few years. Arthouse movies like Terry Chiu’s Open Doom Crescendo and Quentin Dupieux’s Smoking Causes Coughing are similarly toku-infused, and Netflix’s Ultraman: Rising – an American-produced family animation loosely based on the ’60s show – is set for 2024. Even the real article is getting a Western resurgence, with Shin Kamen Rider getting a wide Amazon release and Godzilla Minus-One winning an Oscar for best VFX despite – or, more likely, because of – its abandoning of the series’ signature suitmation effects. (It still cost a lot less than its competitors.)

Hideaki Anno’s Shin Kamen Rider

I’m proud of Hotelitor, and still feel lucky that I got to channel my teenage work experiences through the prism of giant robots punching each other. It’s definitely the most ambitious thing I’ve ever done. My proudest creative moment, though? A few weeks ago, I finally made a bunch of figures based on the wrestling comic I put out a few years ago. I’d wanted to make these figures for years, but only now did the stars of advances in 3D printing technology, sudden free time and a friend buying a bunch of hardware align. They’re only a few centimetres tall, stuck in a single pose – a homage/rip-off of old M.U.S.C.L.E figures from the ’80s. Finally holding one of these things in my hand was insane: the ultimate testament to the power of dumb ideas and force of will made flesh(-coloured resin). You could even transport one in a lunchbox, though I can’t vouch for the food-safety of the materials.

That’s one childhood bucket list item ticked off, then. Maybe one day I’ll mentally weaken to the point where I plough any savings I have into a live-action Hotelitor movie. And if I do, I’ll make sure I get to wear the suit.

—

Josh Hicks is a cartoonist, author and filmmaker working out of Cardiff, Wales.

—

MORE

— ULTRAMAN: The TOP 13 Grooviest Episodes of the Original Series. Click here.

— THE JOY OF KAIJU: A Kaleidoscope of Mutant Inspiration. Click here.