BATMAN WEEK: The former DC head explains why some stories made the cut in the Folio Society’s 85th anniversary collection DC: Batman — and others didn’t…

—

Welcome to BATMAN WEEK 2024 — celebrating the 85th anniversary of the release of Detective Comics #27, on March 30, 1939. Over seven days, you can look forward to all sorts of groovy and offbeat columns, features and cartoons that pay tribute to the greatest comics character in the history of mankind. The article below is former DC Comics President and Publisher Jenette Kahn’s introduction to the just-published anniversary collection DC: Batman, from the Folio Society. Click here for the rest of the BATMAN WEEK features. You’ll be glad you did! — Dan

—

By JENETTE KAHN

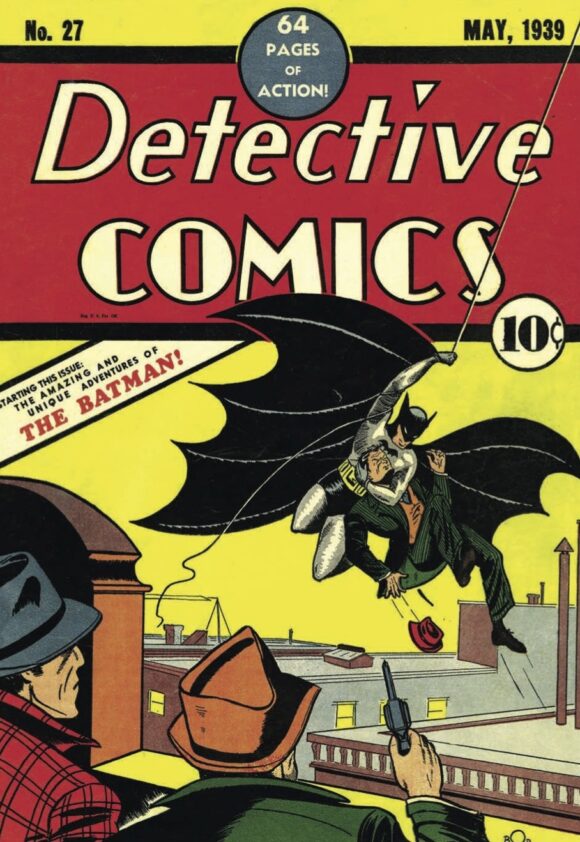

Is there a character more layered, more complex, more compelling, or more divisive than Batman? Amazingly, the template for all these responses can be traced to two comics published in 1939, the year of Batman’s debut. One is Detective Comics #27, which shows Batman in action for the very first time. The second is Detective Comics #33, where a two-page origin story (later repeated in Batman #1) establishes the trauma that turned Batman into an obsessive dark avenger.

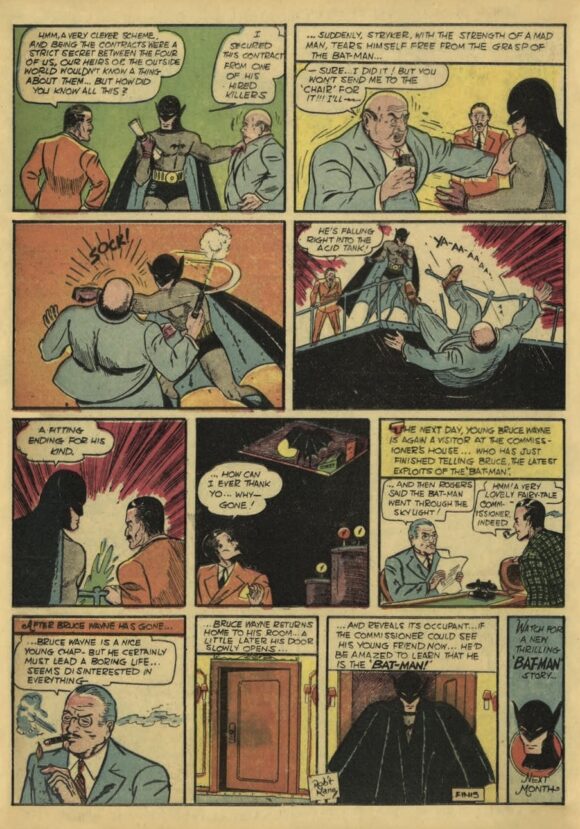

Detective Comics #27’s The Case of the Chemical Syndicate lacks the polish of later iterations, but there is rawness in the telling and a brutality that will be expunged from later comics when the industry adopts the Comics Code in 1954. But here, in 1939, Batman has no compunctions about tossing a murderer to certain death or punching a villain so hard that he falls through a barrier into a vat of acid.

“A fitting death,” Batman declares.

Forty-seven years later, when pundits in Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns defend Batman’s tactics while others proclaim him a fascist, the duality can be traced back to Detective Comics #27.

Themes of duality, of dark and light, of twin identities, of good and evil, of law and lawlessness, and of sanity and madness, thread their way through every decade of Batman comics. As the years have gone by, artists and writers have leaned more and more heavily into the darker aspects of Batman’s persona, but there was also a lighter side in the earlier comics, a world of giant props, banter, and puns that made Batman and Robin beloved by their readers. Even in the later stories, whether through Alfred’s dry wit or the Joker’s twisted humor, we get a glimpse of this too.

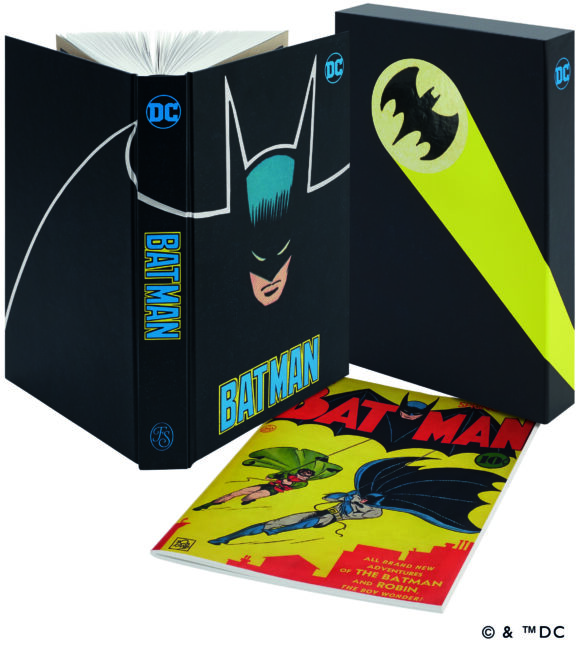

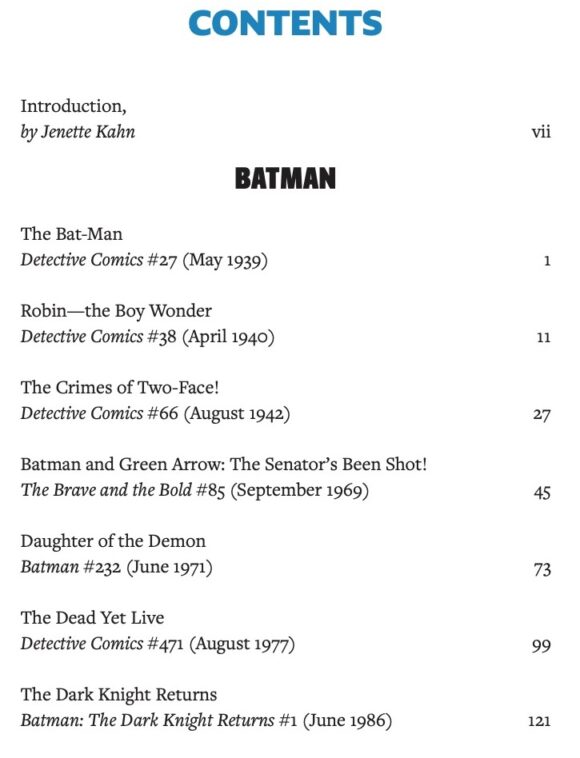

The Folio Society collection includes a facsimile of 1940’s Batman #1

My brother Si and I read all manner of comics, but we had our favorites. Mine without question was Batman. I loved the ingenious plots and his brainy, gaudy villains. But most of all, I loved that he forged his own identity, that he became the Batman through his own relentless efforts. I may have only been seven, but Batman made me believe that I could determine my own path too.

With my lifelong love of Batman, it was easy to say yes when the Folio Society asked if I would curate a deluxe edition of the Caped Crusader’s adventures. But with decades of invention and thousands of stories, how could I ever choose what to include—or even more challenging, what to leave out? Since his debut in 1939, Batman has attracted the very best artists and writers, each one bringing something distinct to deepen the Dark Knight oeuvre. In the end, I opted to include at least one pivotal story from each decade of the 20th century, but there remains a brilliant Batman saga in the outtakes.

Of all the exceptional comics I had to forego because of size constraints, nothing stands out more than Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth. The fusion of Grant’s writing and Dave’s art created one of the greatest Batman stories of all time and plumbed powerful psychological and horror dimensions for all future comics to come.

On the lighter and wonderfully inventive side, I would have loved to include The Joker’s Journal from Detective Comics #193. It’s only in recent years that “meta” has come into use as an adjective, but that would have been the perfect descriptive for this inspired 1953 comic. Still behind bars, the Joker is tasked with running the prison’s newspaper. It’s a galling assignment since he has to print endless stories of triumphant cops. When the Joker escapes, he starts his own newspaper, a veritable Craigslist of crimes that crooks can invest in. But the paper contains more than classifieds. There’s an ongoing comic strip, “Batman the Sapman.” In the Joker’s Journal, Batman gets his very own comic within a comic book about him. It doesn’t get much more meta than that.

There’s another comic I wish there had been space for, The Rainbow Batman from Detective Comics #241. To solve a crime, Batman keeps changing into colorful, eye-catching costumes until we finally see him sporting a rainbow-colored uniform in the last panels of the story. The Rainbow Batman dates from 1957, twenty-one years before the rainbow flag was launched as a symbol of LGBTQ pride, but the gay community has dug into the archives and given an old-fashioned comic contemporary meaning. It’s a fitting tribute not just to this Batman tale but to the ever-changing relationship between reader and story.

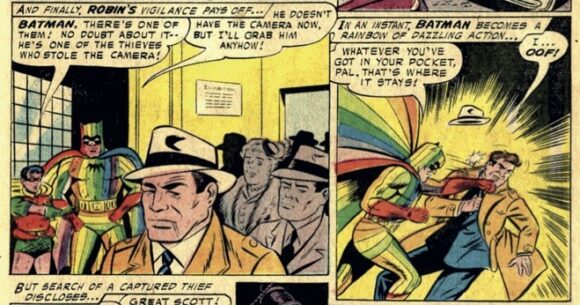

There is one more comic I want to mention, Superman #76 from 1952, the very first meeting of the Caped Crusader and the Man of Steel. Living in separate cities and unbeknownst to one another, Bruce Wayne and Clark Kent decide to take a break and book passage on the cruise ship Varania. Not wanting to miss out, Lois has booked passage too. The two men quickly discover each other’s secret identities and then spend the rest of the voyage battling crime and convincing Lois that neither has anything to hide.

Even as they showcase their different abilities, Batman and Superman feel almost interchangeable. They’re pals, and they continue to be, as they team up over the decades in World’s Finest Comics. But an inevitable fissure is coming. By the time of The Dark Knight Returns, the men are polar opposites. Superman, positive, law-abiding, and shaped by the loving Kents, belongs to the day. Batman, grim, obsessive, and filled with rage, belongs to the night.

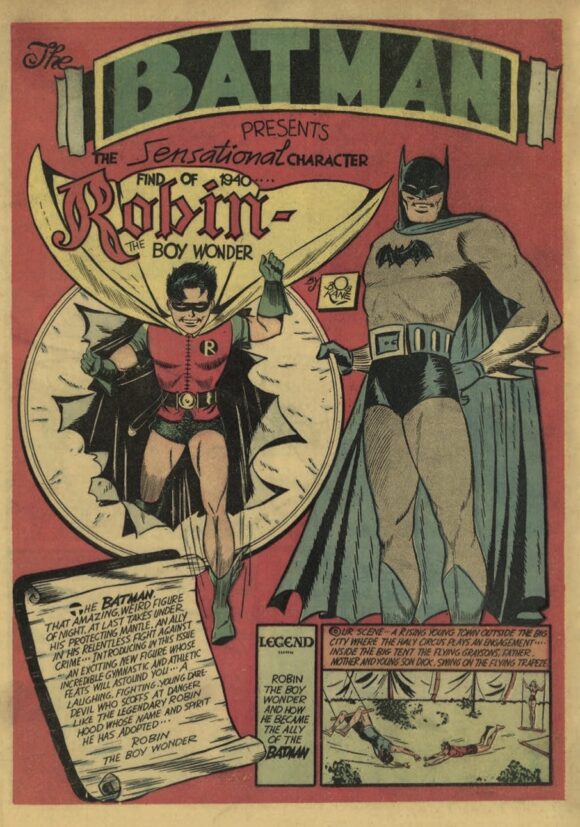

Bob Kane, Bill Finger, and Jerry Robinson, the great Batman triumvirate, immediately saw the need to lighten the dark tenor of Batman’s world, and they did so just one year later by introducing Robin, or Dick Grayson, in Detective Comics #38. Along with his youth and youthful appeal, Robin was an invigorating counterpoint to Batman, and gave Batman someone to talk to. Like Bruce, a horrified Dick watched as his parents were cut down, but in Bruce he had a caring guardian, and that made all the difference. Where Bruce’s Batman is somber, single-minded, and driven, Dick’s Robin is ebullient, freewheeling, and eager for adventure.

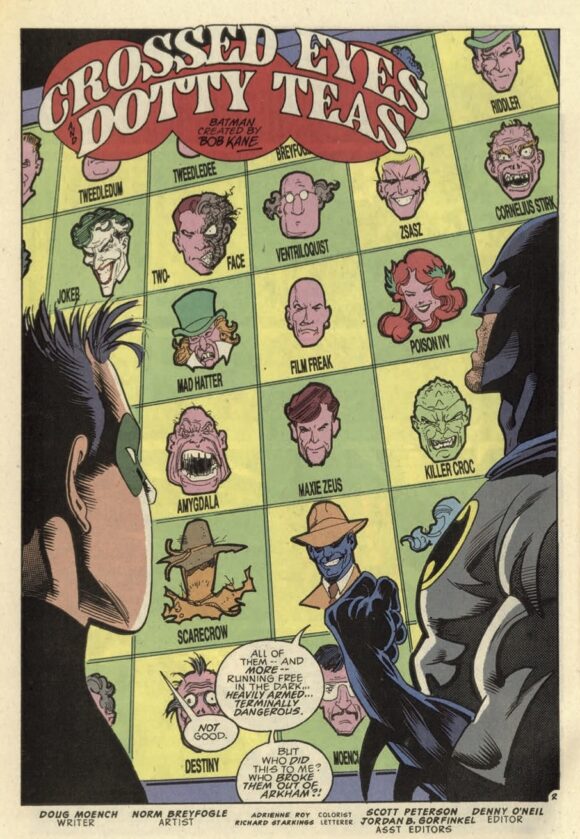

As compelling as Batman might have been even with the addition of Robin, it’s his panoply of villains that has cemented the devotion of his readers. In all of comics, there is no rogue’s gallery more garish, more inspired, or more maniacal than the Joker, Two-Face, the Penguin, and the Scarecrow. Their sanity is always in question and brings into question Batman’s own. Forged by trauma, Batman is just steps away from madness. He has gazed into the abyss and the abyss has looked back into him.

Trauma is a through-line in the Batman mythology. It has made psychopaths of Batman’s foes and brought him to the edge of madness himself. Batman’s battle is not just against criminals and crime. He fears the day he’ll look into a mirror and see, not Bruce Wayne’s face, but the Joker’s.

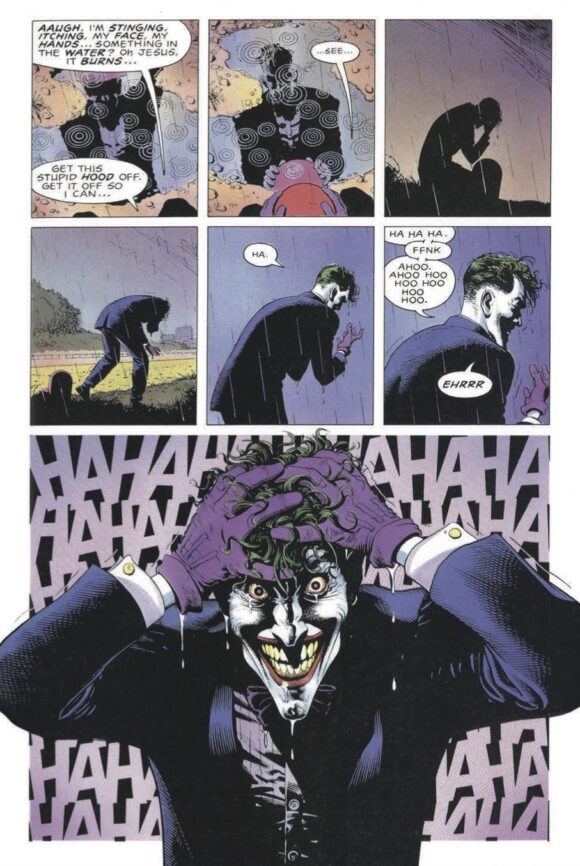

From the earliest issues, Bob Kane, Bill Finger, and Jerry Robinson understood that Batman’s villains had to inhabit the same dark, surreal world that he did. They began by introducing the Joker in 1940 in Batman #1. Although we’re not yet privy to his origin, a story that will be told in 1951 in Detective Comics #168 and mined years later in Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s incomparable The Killing Joke, the Joker’s freakishness is immediately established by his chalk-white face and the rictus grins of his victims that reflect his own distorted visage. The Joker will soon become a lighter character, more prankster than killer, but it’s his earliest incarnation that will inspire artists and writers as the Batman stories take a dystopian turn.

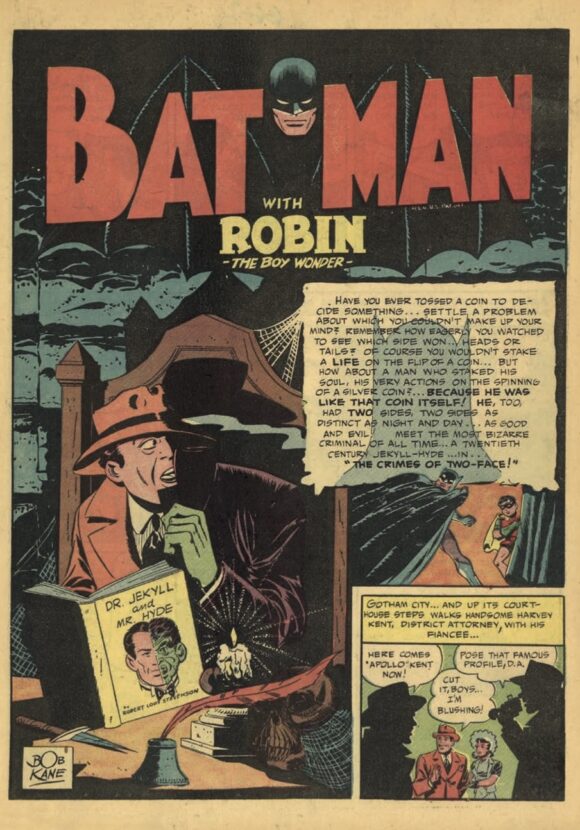

Just as trauma weaves through every decade of Batman comics, so does the theme of duality. One of the most powerful examples can be found in Detective Comics #66, the 1942 comic in which Two-Face is introduced. Bob Kane and Bill Finger weren’t shy about their inspiration. On the very first page of the story, we see a fearful Harvey Dent reading Robert Louis Stevenson’s horror classic, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. But Bob and Bill went further. They divided Harvey’s person in half, one side the handsome district attorney, the other a grotesque parody. And then, with a stroke of genius, they added a coin where one side is unblemished, the other defaced. No matter how large or consequential, the actions Harvey takes rest on the mere flip of the coin. Here, and throughout the Batman oeuvre, there’s a line as thin as a coin between good and evil, between sanity and madness.

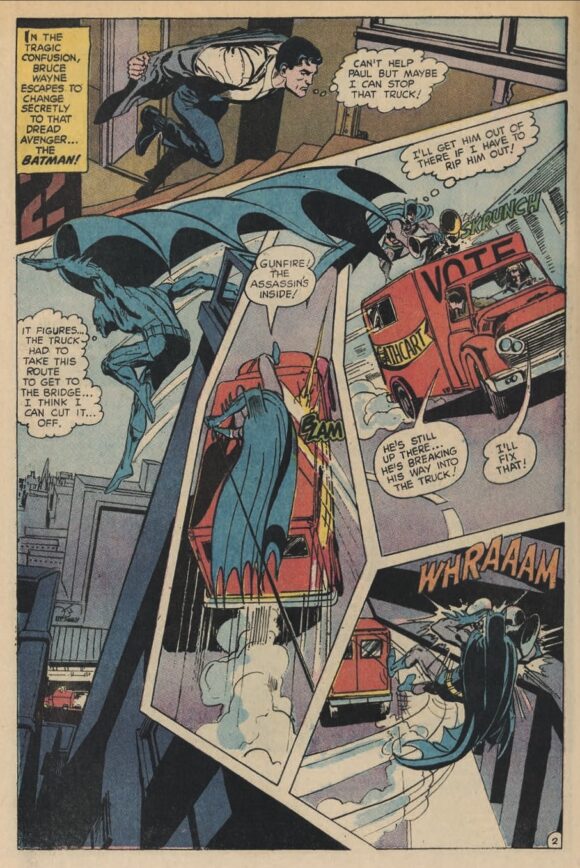

All comics are a synthesis of story and art, and the very best art heightens a story well beyond its words. When Neal Adams burst onto the scene, he broke with the traditional panel structure and sliced the page to create the kind of movement and dynamism one might see in movies. He also brought more realism and expression to his characters, and this, combined with his filmic sensibility, set a standard that other artists imitated, riffed on, and made their own.

One of Neal’s first depictions of Batman appears in The Brave and the Bold #85 in 1969. He’s flexing his new artistic muscles, and his storytelling doesn’t yet exhibit the control that he’ll demonstrate in the classic Ra’s al Ghul saga, but there’s no doubting the thrill of his approach. It ripples through the industry, lays the foundation for Neal’s iconic status, and ushers in an exciting new era in the art of comics.

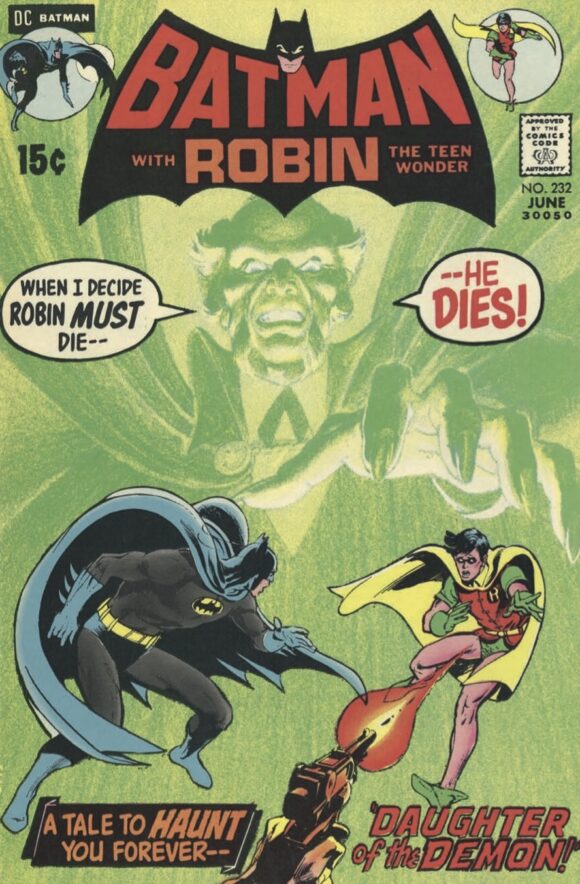

The perfect fusion of writer and artist, of story and art, occurs just two years later when Neal teams up with Denny O’Neil on a series of hugely influential comics. In Batman #232, Denny and Neal, along with editor Julius Schwartz, introduced Ra’s al Ghul, a supervillain whose brilliance, power, and reach make him a formidable opponent who will sorely test Batman throughout the years. In the same comic, Neal also established the definitive depiction of Ra’s’ daughter Talia whom Denny created with artist Bob Brown for Detective Comics #411. An alluring outlaw like Catwoman before her, she will engage Batman in a seductive dance that underscores his ambivalent attraction to crime.

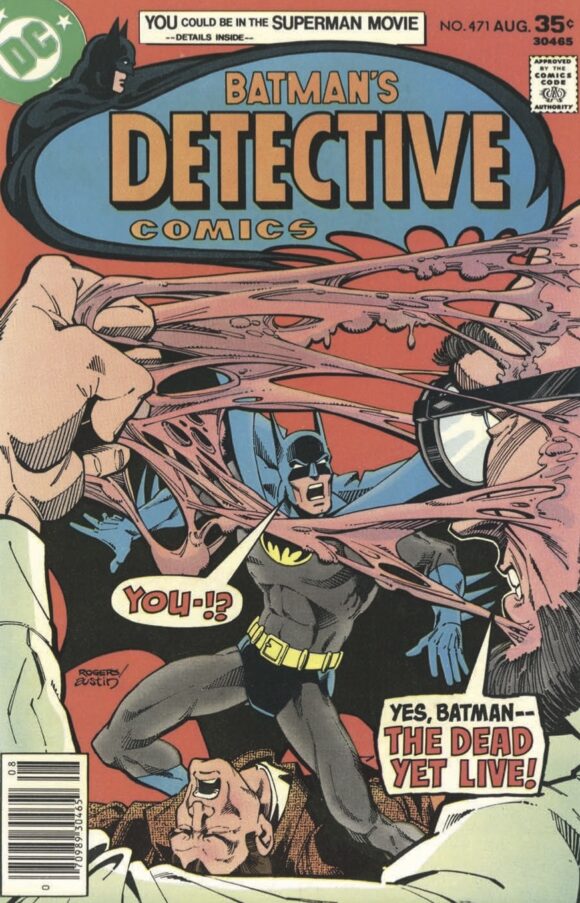

As thrilling as Neal’s art was and as heavily as it influenced countless other artists who drew on his techniques, there was a countermovement that can first be seen in Marshall Rogers’ work with Steve Englehart in their classic 1977 Detective Comics collaboration. There are many reasons the series stood out: It had a pulpy sensibility that paid homage to Batman’s dark roots; it introduced Silver St Cloud, a beautiful, intelligent socialite who grounded Bruce in a real relationship; it created a sustained narrative arc over its eight-issue run, an approach quite novel at the time; and it played with ideas of sanity and madness, ideas that would gain even more traction in later Batman issues.

While Marshall’s art enhances every aspect of the story, it breaks from Neal’s acclaimed illusions of deep, dimensional space and splashy page configurations. Instead, Marshall flattens the space and returns to the discipline of a panel structure, but with a keen understanding of how to use the restrictions of the panels’ frames for maximum power and effect. It feels tremendously modern.

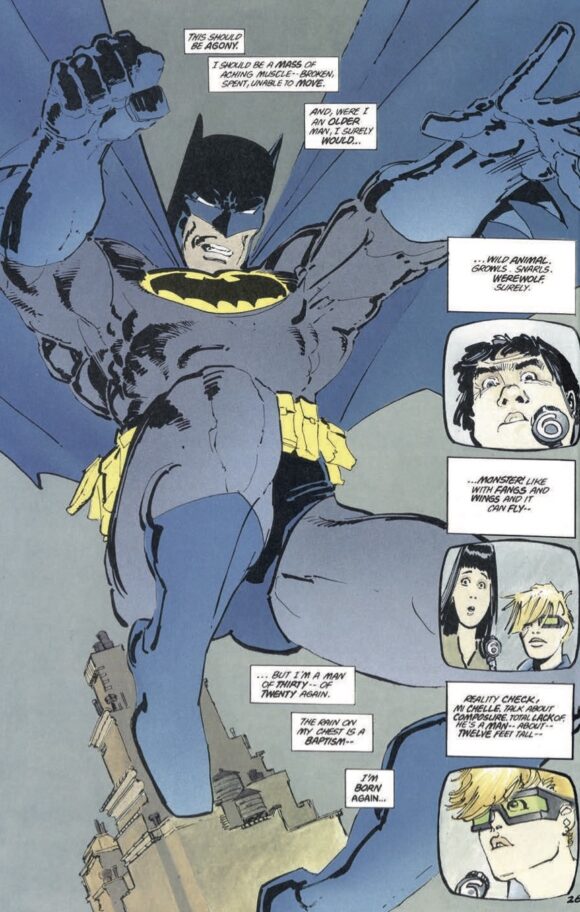

Steve and Marshall’s depiction of the Caped Crusader ushered in a new era of Batman stories and was a dark harbinger of what was to come. Nine years later, Frank Miller turned the Batman world on its head in a comic that shattered all norms, The Dark Knight Returns. Devastated by the death of Jason Todd who had replaced Dick Grayson as Robin, Bruce had given up crime-fighting and retreated into seclusion. But watching the murderous Mutants rampage through Gotham, he can no longer nurse his self-imposed isolation. Ten years after Jason’s death, a fifty-five-year-old Bruce dons the cowl of the Batman again.

The Dark Knight Returns is considered one of the greatest and most influential comics ever published. And no wonder. It brings Batman’s foes to the fore in new and terrifying iterations; it introduces a canny, courageous Robin who refreshingly is a girl; it explores the diminution that inevitably comes with age; and it pits two of the greatest heroes against one another, Batman, a raging vigilante, Superman, a government tool. Frank’s art is as thrilling as his story, and Lynn Varley’s paints create an emotionally nuanced palette only seen once before, in her collaboration with Frank on Ronin.

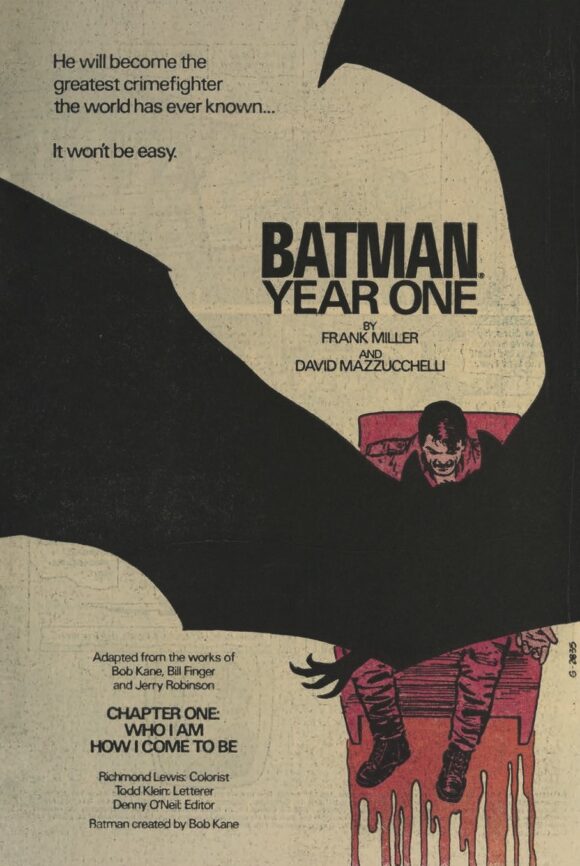

In The Dark Knight Returns, Frank cast a light on a middle-aged Batman where age has taken a toll. Just one year later, in Batman: Year One, Frank looked back thirty years at a youthful Bruce Wayne as he struggles to find his calling. The trauma that sent him searching eighteen years before gets a heartbreaking rendition in David Mazzucchelli’s art. And with that same bleak, evocative art, Frank and Dave establish a harrowing, crime-ridden Gotham that will be the template for decades to come.

A young Jim Gordon is a key player in Batman: Year One, an incorruptible cop in a cesspool of corruption. A much older Jim Gordon on the verge of retirement is also a key figure in Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s brilliant The Killing Joke. Like The Dark Knight Returns, it’s considered one of the greatest comics of all time, with a telling of the Joker’s origins that is as empathetic as it is dreadful.

A ghastly day of appalling events has cost the Joker his sanity, and in The Killing Joke, the Joker is determined to prove that anyone who suffers a similar set of traumas will lose his sanity too. But after the Joker shoots Barbara Gordon and shows Jim Gordon naked pictures of his daughter paralyzed and in excruciating pain, and after he, too, is stripped naked, paraded through fairgrounds, tortured with terrifying images in a carnival ride, and thrust into a cage to be gawked at, Jim Gordon doesn’t crack. In a story as dark and desperate as The Killing Joke, Jim Gordon’s steadfastness delivers a message of hope.

1986 gave us The Dark Knight Returns, 1987 Batman: Year One, 1988 The Killing Joke, and 1989 Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth. Pinnacles of story and art, these revered comics continue to shape all Batman stories to come.

Batman: Shadow of the Bat #1 launched a 94-issue saga that fittingly followed Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum with another exploration of sanity and madness. In a four-part arc written by Alan Grant and drawn by Norm Breyfogle, Jeremiah Arkham, the nephew of the asylum’s founder Amadeus Arkham, has taken over. Jeremiah destroys the old psychiatric institution in a conflagration and builds it anew, basing the floor plan on a classical labyrinth structure.

A guard observes that Jeremiah will end up like his uncle who descended into madness, and noting how tightly wound Jeremiah is and how brutally he treats his patients, we share the guard’s assessment. So does Batman. In an effort to get inside and expose the institution’s horrors, Batman has to pretend to be mad. But once admitted as a patient, he too becomes a prisoner of this hellhole, where a ruthless Jeremiah vows to cure his “insanity.”

There are so many other great Batman storylines from the 1990s — Venom, Gothic, The Long Halloween, Prey, Birth of the Demon, No Man’s Land — to name just some of the standouts. With apologies to all the ones I’ve left out, I’ve chosen Knightfall to close out this volume because of its grand scale and because it puts Bane front and center, raising him to supervillain status.

Over the years, newly introduced Batman villains have come and gone, with only a few, like Ra’s al Ghul, ascending to Pantheon status. But Bane, created by Chuck Dixon, Graham Nolan, Breyfogle and Doug Moench is another rare exception. Given free rein in Knightfall, he runs roughshod over Batman, ultimately breaking Batman’s back and his spirit along with it. The road to recovery will be long and painful as Gotham reels from Batman’s absence.

But Gotham is Batman’s city, and he will return, bringing with him all the themes of duality, of dark and light, of twin identities, of good and evil, of law and lawlessness, and of sanity and madness that are at the very heart of his character.

—

The stories in DC: Batman were scanned from original copies in the DC archives and have been reproduced in 10” x 7” format. It is available for $100 exclusively from the Folio Society. This introduction ran in slightly different form in the book.

—

MORE

— The BATMAN WEEK 2024 INDEX! Click here.

— JERRY ROBINSON: How a Tennis Match Led Me to the World of BATMAN. Click here.

March 25, 2024

I understand there’s a lot of chaff in the character’s publishing history, especially during the “fighting aliens” phase of the silver age, but a 27 year jump, right over most of the 40s and completely over the “ new look” run, is inexcusable for a book of this type.

March 25, 2024

Truth.

March 25, 2024

The folio book was unbalanced in its story selection. The 50’s are completely skipped over and so is the new look era of the 60’s. Also, this collection stops in early 1993.

I thought Kahn’s choice of Golden Age stories for the prior DC Folio collection was not ideal but her selection of stories for this new Batman volume is even more uneven and a disservice to fans, whether they be newer, casual readers or die hard fans of this character.

The Batman Folio book is 320 pages but one of the Marvel Folio editions have gone up to 368! That is 48 pages they could have used to include a story from the 50’s (A Dick Sprang World’s Finest Superman team up perhaps?), new look 60’s era (Barbara Gordon’s Batgirl debut perhaps?). Kahn has left a gaping hole in this retrospective anthology.

The 1988 Greatest Batman Stories Ever Told and Greatest Joker Stories Ever Told volumes also have a better balance of stories and time periods. You can find them in good condition for a good price on eBay. The Joker volume is especially well curated!

March 25, 2024

That’s an impossible task to cover 85 years of storytelling in 300-ish pages, but I will note there is a huge gap between 1942 and 1969, particularly since the 1969 entry B&B #85 belongs more to the 1970s aesthetic than to what came before. Jennette’s description of The Joker’s Journal sounds like fun, and from what I can tell has almost never been reprinted, apart from the comprehensive omnibus format. Would have been nice to include such a deep cut!

March 25, 2024

TRUTH!

March 26, 2024

Wow! I’m overwhelmed reading this! I read a lot of Batman-related comics starting in the 70s (and a bunch of back issues and reprints) and this is a blast down memory lane! Thank you!

March 27, 2024

Oh yes! Let’s once again show Barbara Gordon being shot and raped. It was sick then and sicker now.