GODZILLA vs. KONG opens this week and we take a loving INSIDE LOOK at the world of huge creatures that live to pound each other into submission…

Superfan Promotions’ David Hyde is one of comics’ top PR reps and a longtime friend. (He’s the first person I met in the biz more than a decade ago.) Obviously, we share a lot of the same loves – including Godzilla.

Both of us – separately, with our sons — recently plowed through the Criterion Collection’s spectacular Showa Era Godzilla boxed set and so when David pitched a short series on THE JOY OF KAIJU, I couldn’t contain myself.

So here’s the first in a three-part series running this week, timed to the release of Godzilla vs. Kong – featuring a litany of A-List comics creators like Mike Mignola, Scott Snyder, Geof Darrow and many, many more.

Dig it.

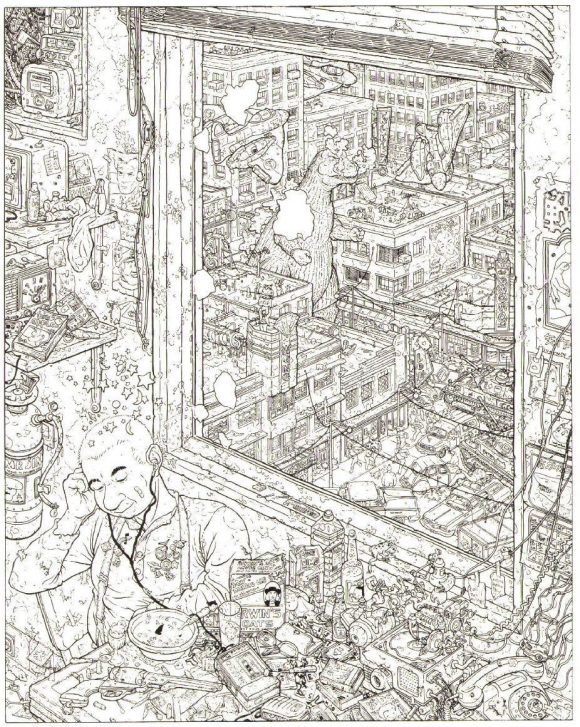

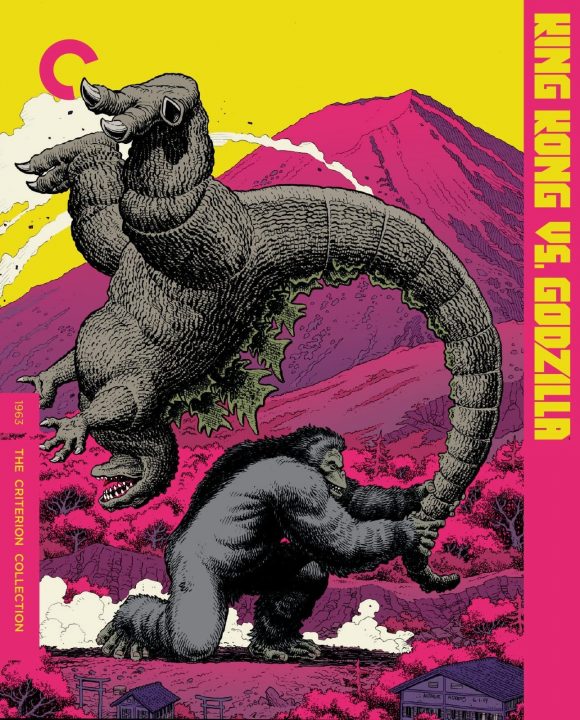

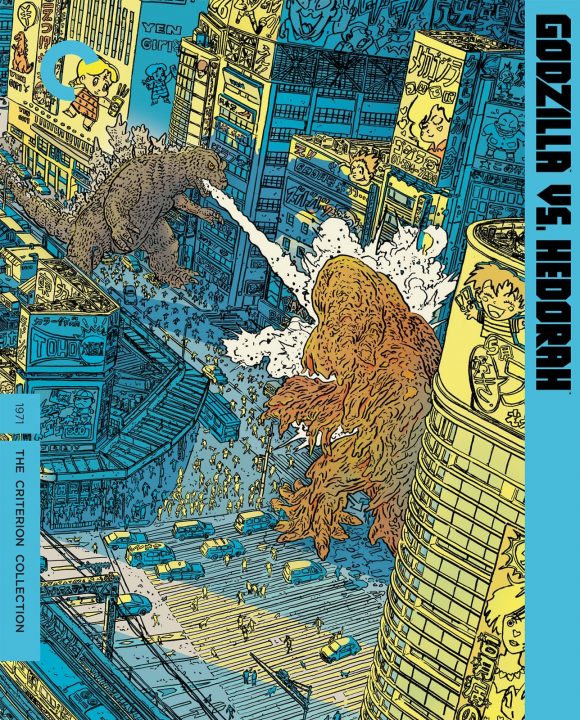

Yuko Shimizu, from the Criterion Collection boxed set

—

By DAVID HYDE

Ishirō Honda’s original Godzilla film spoke to his country’s collective anxiety about nuclear Armageddon. Many of the films that followed — while often still addressing environmental and global concerns — had an entirely different paranoia that sparked their creation: film executives’ fear of the power of television and diminishing box office returns.

As Tōhō Studios produced more and more Godzilla films for their growing fanbase of latchkey kids and rebellious teenagers, the kaiju got stronger and stranger.

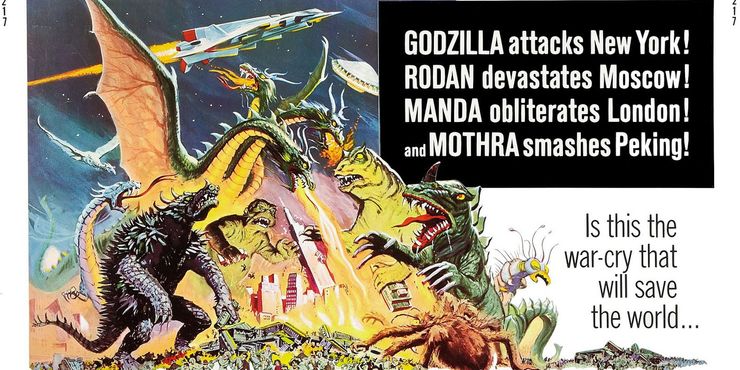

What’s better than two kaiju battling? Three kaiju wreaking havoc on the big screen! Anguirus! Mothra! Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster! Rodan! Ebirah! Kumonga! Gabara! Hedorah! Gigan! Megalon! Titanosaurus! The kaiju that Godzilla battled in the Shōwa Era films provided a kaleidoscope of colorful mutant menace for our protagonist.

And Kaiju were just the beginning of this insane worldbuilding.

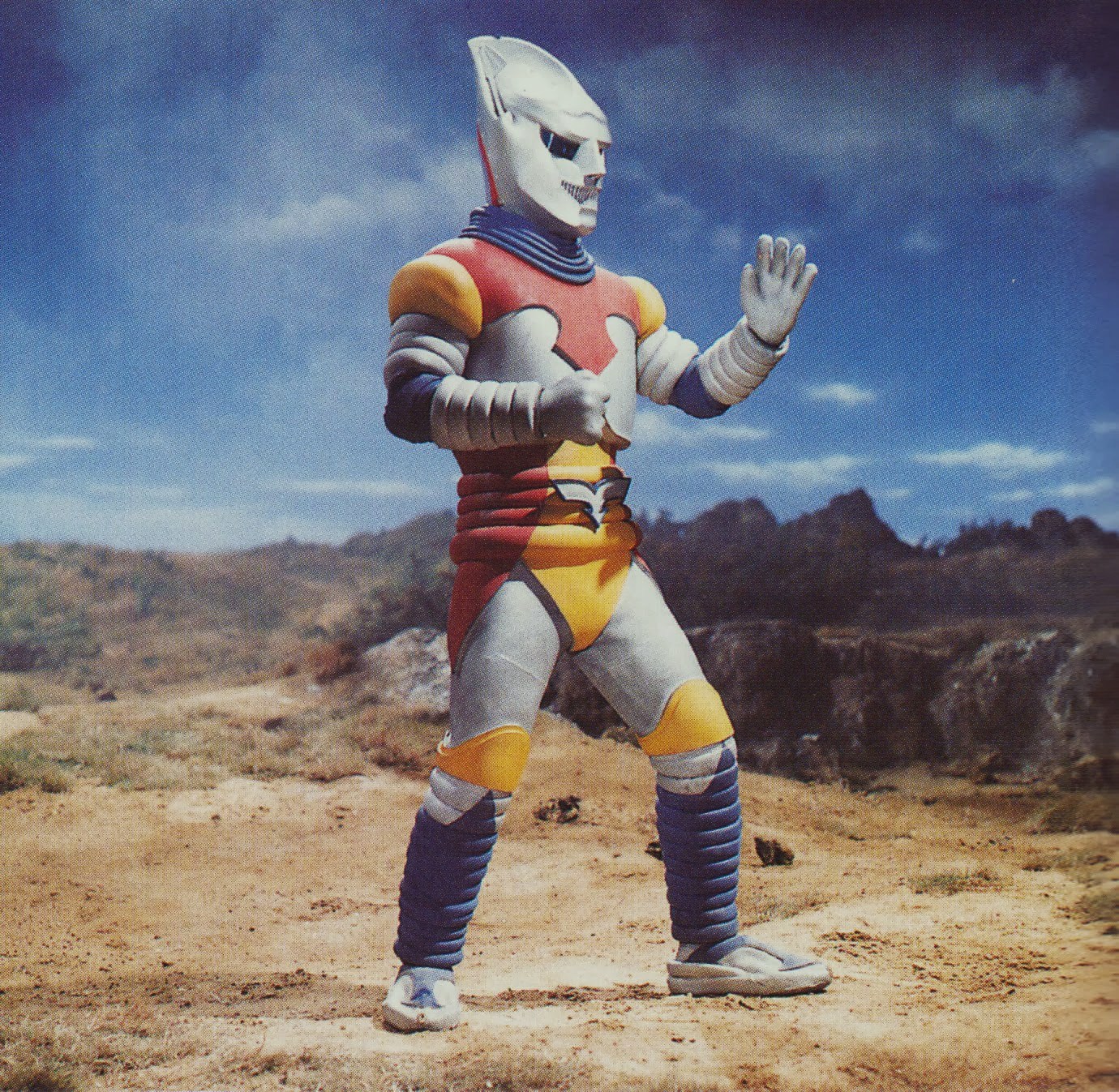

Meet Mechagodzilla!

Here’s Jet Jaguar!

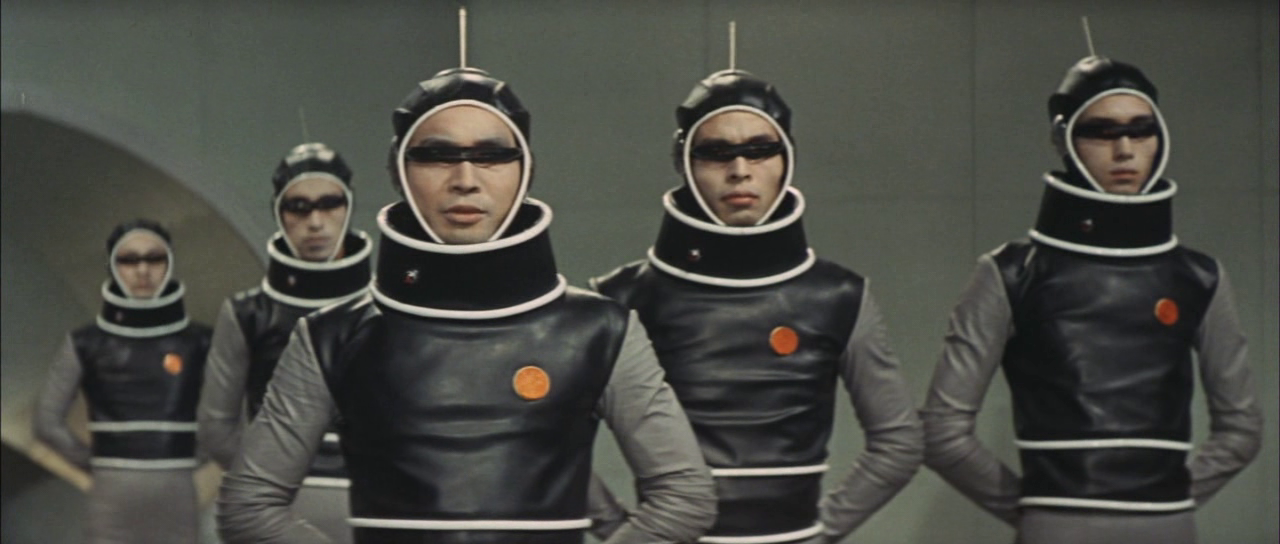

Welcome to Black Hole Planet 3! This is Planet X!

Godzilla’s rogue’s gallery — with their increasingly bizarre names and surreal powers — feels like they could have originated in the pages of manga or American comics. Perhaps that’s why there’s so many comic book adaptations of Godzilla’s adventures…. (And also, maybe, why the art director for the Criterion Collection commissioned comic book artists to create art for their amazing, oversized, deluxe boxed set of the Shōwa Era films.)

And yet, as I have discovered, comic book writers and artists tend to fall into one of two camps. There are Godzilla superfans, who can recall, with precise detail, the mythology of kaiju. And then there are others who might distantly recall watching a Godzilla movie or two as a child, but have, at best, a passive interest in the King of the Monsters. Sometimes the possibility of the monster is more interesting than the monster itself.

Mike Mignola

“I’ve actually never cared at all about Godzilla. Or any of that kind of stuff. I love the IDEA of Godzilla and what I REALLY like is listening to Geof Darrow and Art Adams talk about Godzilla.” — Mike Mignola (Hellboy, Mike Mignola: The Quarantine Sketchbook)

Geof Darrow

“Godzilla came out of Tokyo Bay the same year I came out of Agnes Darrow, both of us with differing results and career choices. One of my favorite Godzilla memories is living in Tokyo and watching a Godzilla nightly film festival and seeing him tromp around places I had been to that very same day. Once again with differing results.” — Geof Darrow (Shaolin Cowboy, Lead Poisoning: The Pencil Art of Geof Darrow)

Darrow

“Although I have never been a diehard Godzilla fan (I don’t know who the creator was, who wore the suit or who made the sandwiches at the craft service table) the big lizard is part of some of my fondest childhood memories, laying on the floor in our small apartment and watching Tom Hatten on KTLA’s family film festival. Mr. Hatten was my internet in the pre-internet days. He would bring me entertainment from places and eras that a poor latchkey kid from Southern California would never have known about on his own. Godzilla, like comics, was a springboard to adventures that continued in my mind long after the movie ended; in my imagination Godzilla battled Transformers while Spider-Man looked on. Godzilla and its creators encouraged me to make stories for the sheer joy that came in make believe.” — Marco Finnegan (Lizard in a Zoot Suit; Last Fair Deal Gone Down)

***

1962 was the 30th anniversary of Tōhō. The studio planned to celebrate this milestone with a slew of high-profile releases, including Sanjuro (the sequel to Kurosawa’s smash hit from 1961, Yojimbo), director Hiroshi Inagaki’s seminal 47 Samurai, a biopic about the novelist and poet Fumiko Hayashi titled Lonely Lane, and the third Godzilla film: King Kong vs Godzilla.

King Kong vs Godzilla was made possible after Tōhō secured permission from RKO to use Kong and the film marked the first time that both creatures appeared on film in color and widescreen. An Americanized version of the film would debut in the States the following year. Godzilla was a global star.

Arthur Adams

It had been eight years since Ishirō Honda had directed Godzilla. (The director had not returned for the subpar and entirely skippable sequel Godzilla Raids Again.)

It was a new era in Japan, modern and fast. In the film, the head of Pacific Pharmaceuticals is eager to find a gimmick to boost the sagging television ratings of the shows that his company sponsors. The company comes up with an ingenious solution: they will travel to the remote Faro Island to locate and exploit a mysterious monster, who turns out to be King Kong, in order to drum up publicity and ratings. Kong is drugged, captured, and transported by boat to Japan. Meanwhile, Godzilla is unleashed and, as the title suggests, hijinks quickly ensue.

In 1962, wrestling was all the craze in Japan. And what’s not to love about two giant monsters battling? Eiji Tsuburaya was encouraged by Tōhō executives to bring a lighter, more comedic tone to the staging of the violence and special effects. Honda did not agree. He preferred the film’s humor to be contained to the satire of the television and entertainment industry.

But King Kong vs. Godzilla was, forgive me, a monster success. More people watched the movie in theaters in Japan than any other Godzilla film to date. And, in future installments, Tōhō and Tsuburaya would only further dial up the humor and madcap antics.

The movie ends with both monsters tumbling off a cliff, falling into the Pacific Ocean. This non-ending would soon become a recurring motif. Why crown a definitive champion, when it might limit profits from a potential sequel?

Godzilla movies, not to mention Ultraman and tokusatsu superheroes, had an unmistakable impact on a generation of comic book creators. Acclaimed writers and artists, including Arthur Adams, Geof Darrow, Joshua Hale Fialkov, Phil Hester, John Layman, Alberto Ponticelli, Eric Powell, Ansis Puriņš, James Stokoe and Duane Swierczynski, have all contributed to Godzilla’s comic book adventures. (Let’s also not forget Marvel’s popular series back in the Bronze Age.)

Ansis Puriņš

“I was able to present to Haruo Nakajima and his daughter a bio comic I had drawn about his life at a special (Godzilla collectors) dinner that was arranged for us. I had previously prepared a formal intro letter in Japanese explaining this comic and its creation. Nakajima-San and his daughter sat and slowly read my story while I nervously watched, sitting across a banquet table. (This was at a Japanese bar on Newbury Street the night before a comic con in Boston.) He suddenly stood up, walked over to me and bowed deeply to me. It was an unforgettable moment. This was all happening while I sat next to movie star Akira Takarada. He kept pouring shots of pink wine as he told me tales of TV star Nick “The Rebel” Adams and how he was ‘a horny guy!’ Best night ever.”—Ansis Puriņš (Super Magic Forest)

The Shōwa era films zigzag from satire, to psychedelic experimentation, to pulp, to camp, and back again. As the spectacle and the storytelling became more over the top, it seemed like there were no limits.

Then, in 1970, Godzilla special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya died at the age of 68. Later that year, Honda’s employment contract with Tōhō expired. The director was offered a television contract, but he decided it was time to move on.

Darrow

New blood was needed. Enter Yoshimitsu Banno. Inspired by the desire to clean up the pollution he had seen in Yokkaichi’s industrial district, Banno utilized his Godzilla film — 1971’s Godzilla vs. Hedorah — as a vehicle to spread environmental awareness, much as Honda had utilized the original film to address nuclear Armageddon years ago.

Banno had worked as assistant director on a number of Kurosawa’s classic films, including both The Hidden Fortress (1958) and Throne of Blood (1957), but there’s nothing in those films that can prepare you for the psychedelic and experimental storytelling on display in Godzilla vs. Hedorah.

Godzilla vs. Hedorah

A conventional summary of Godzilla vs. Hedorah would suggest that it’s a creature feature in which Godzilla battles his newest nemesis, a smog monster. But that would leave out all the wonderfully strange, subversive and psychedelic-fueled details that make the movie so memorable, if wildly, willfully uneven, and uncategorizable in its tone.

The film includes charming animation sequences; a trippy hilltop dance party; genuine horrific imagery of wholesale slaughter; and also one of the most silly (and controversial) sequences in Godzilla‘s history, in which he slides on his tail to fly. Some (including my family) consider Godzilla vs. Hedorah essential viewing, but the Godzilla fandom is deeply divided about the film’s merits.

Godzilla vs. Hedorah’s go-for-broke sensibility, which predates the full throttle, bizarre storytelling of Nobuhiko Obayashi’s horror comedy House (1977), is arguably best summed up by this dialogue from the film’s party sequence: “There’s no place else to go and pretty soon we’ll all be dead, so forget it! Enjoy yourself! Let’s sing and dance while we can! Come on, blow your mind!”

Godzilla vs. Hedorah

“What I love about Godzilla is the world of stories surrounding him. Goofy, complex, harrowing, somewhere in between or outside all three, what’s really important is the why. Sure, there’s the rush of excitement that comes from watching the King of the Monsters be conquered by human ingenuity (or help humans defeat another monster, depending on the film), but no matter what, Godzilla stories are brilliant expressions of what people do when they’re tested in the face of disaster. With all of their ostentatiousness and occasional camp, Godzilla is not just a metaphor for the horrors humanity has wrought, but for the ancient uncanniness of our world, and our tenuous place in it. Are we really the masters of this planet? Or are we one disaster away from becoming fossils of the past?”—Samuel Sattin (Bezkamp, Glint)

Mignola

Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975) was the final Godzilla film of the Shōwa era and the last film that Ishirō Honda directed. It was also, notably, the first and only Godzilla script written by a woman. The film was the least financially successful Godzilla film, but don’t let that fool you. It’s both a ton of fun and a worthy send-off for Honda and the Shōwa Era.

Terror of Mechagodzilla brings together so many of the best aspects of kaiju moviemaking: memorable monsters, evil aliens, a terrific score, mad scientists, and melodramatic, memorable dialogue. Witness:

Tsuda: Your heart is frozen and dry. Who’d love a cyborg, a person who is not a person? So remember, forget about Earthlings. They’re no concern of yours. There’s only one emotion that controls your mind. What emotion is that? What controls you?

Katsura Mafune: [listlessly] Vengeance and hate. Revenge.

Tsuda: Quite right. That’s good.

Terror of Mechagodzilla feels like a mashup of a classic era Bond film and a first-rate kaiju story. Watching it now, years after its release, the film makes me feel deeply nostalgic, not for the film or even for the characters, but for the retro future of the 1970s: with its metallic bodysuits; (largely tame) blasters; giant, super smart (and super slow) blinking computers; and the implicit promise that our future will improve upon our present circumstances.

Terror of Mechagodzilla ends with the King of the Monsters returning, once more, to the Pacific Ocean. Akira Ifube’s score sounds a little melancholy as the film wraps. It’s an elegiac goodbye to an era of widespread weirdness and kaiju attacks, one that continues to inspire to this day.

“Two things stick in my head about Godzilla. The first is Godzilla the metaphor, the way that we saw the horrors of red tape and war. The other is how, the other day, I gave the little kid next door one of my Godzilla toys and he lit up. For Godzilla to be a lasting metaphor for the horrors inflicted on the Japanese and also a creature that ignites the imagination of children is something most of us creators could only dream of producing.”—Danny Lore (Quarter Killer, James Bond)

—

Many of the Shōwa Era Godzilla films are currently streaming on HBO Max and ComiXology is currently having a sale on IDW’s Godzilla comics.

References: The Criterion boxed set liner notes; Ishirō Honda: A Life in Film, From Godzilla to Kurosawa by Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski; the Secret Movie Club.

—

NEXT: You’re Never Too Old for GODZILLA. Click here.

—

MORE

— The Ultimate Battle! GODZILLA VS. THE MARVEL UNIVERSE. Click here.

— INSIDE LOOK: GODZILLA’s 1970s Monster Merchandise Bonanza. Click here.