From Kirby & Lee to Pekar …

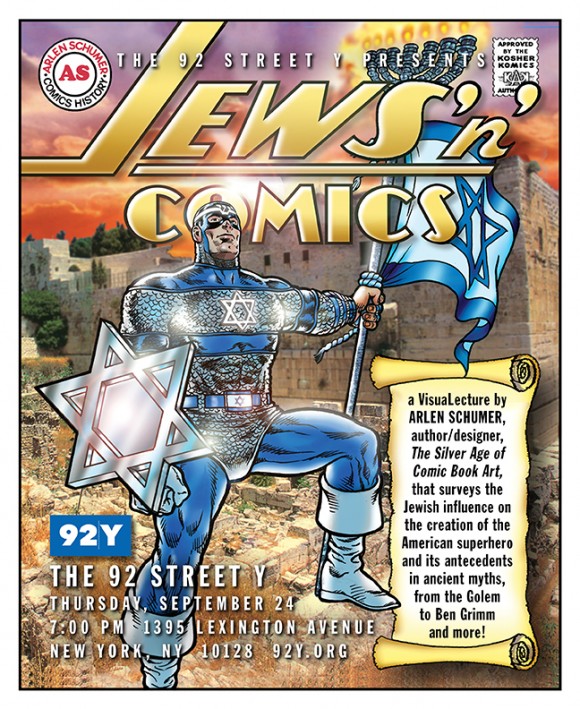

The Jewish High Holy Days are upon us, so we’ve invited Arlen Schumer — whose lecture Jews ‘N’ Comics is 9/24 in NYC (more details here and here) — to discuss the people who formed the backbone of the American comic book.

This series is running in four parts, listing the 13 Most Influential in chronological order. (And yes, the 13 is a bit of a misnomer because in some cases, an entry is for a creative team.)

Part 1. From Gaines to Siegel and Shuster. Click here.

Part 2. From Kane & Finger to Will Eisner. Click here.

Part 3. From Bill Gaines to Julius Schwartz. Click here.

—

By ARLEN SCHUMER

Jack Kirby, Stan Lee (nee Stanley Martin Lieber) & Martin (nee Moe) Goodman

The prime architects of the Marvel Comics revolution in the 1960s—the Silver Age of comics—were artist/writer Jack Kirby, editor/writer Stan Lee and publisher Martin Goodman (Lee’s uncle), and all were sons of immigrant Jews: Kirby’s from Austria, Lee’s from Romania, and Goodman’s from Lithuania.

Together, they turned Atlas Comics, a tiny comic-book company drying up at the end of the ’50s, into the game-changing, trend-setting, underdog-turned-top dog Marvel Comics of the 1960s.

Kirby was the consummate comic-book creator and storyteller. The stories he told at Marvel Comics during the Silver Age, arguably Kirby’s greatest and most influential body of work, were a wellspring of invention the likes of which had never been seen in the comic-book medium—and has never since been duplicated.

The Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Thor, Captain America, the X-Men, the Silver Surfer, the Black Panther, the Inhumans—the “blitz” of timeless Marvel characters Kirby helped bring to life is almost endless.

Kirby would draw his stories out like silent movies on paper, with margin notes for Lee to follow, to dialogue Kirby’s stories. This became known as the Marvel Method, where the artist was also the “writer” and the writer only wrote the dialogue and captions. This freed up Lee the writer to do what

Lee the editor did best: sell the Marvel line editorially to his growing fan base of Baby Boomers weaned on the more staid, conventional, conservative DC line.

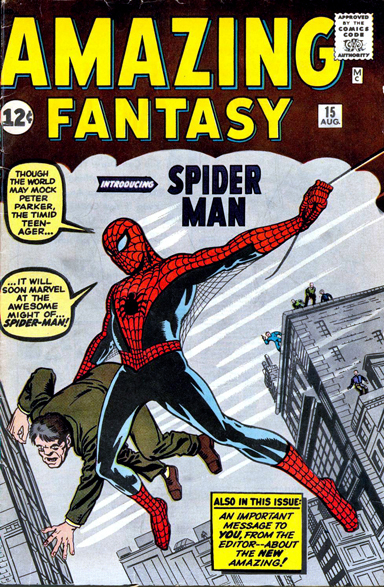

Lee’s dialogue was snappy and alive, characters like the Fantastic Four argued and fought amongst themselves, Spider-Man was only it in for the money, the rampaging Hulk was just misunderstood: The postwar zeitgeist of the antihero was seized upon by Lee and turned into the super-antihero, or “Super Heroes with Super Problems” (the title of the first major media coverage of Marvel Comics, the lead story of the January 9, 1966 New York Herald Tribune Sunday magazine).

If the super-neuroses of a character like Spider-Man’s Peter Parker were only thinly disguised nebbishy Jewish stereotypes, they were ameliorated by Lee’s avuncular, first-person presence in the letters columns, and in proto-Andy Rooney-type forums like “Stan’s Soapbox,” which created an us-against-the-world (i.e., DC Comics) bond with his readers not seen between a comic company and its audience since the halcyon days of EC Comics a decade earlier.

And Lee’s uncle, publisher Martin Goodman, who had been around since the dawn of the Golden Age of comics—when Marvel was known as Timely Comics—helped make it all possible, for better and for worse. For all of his behind-the-scenes chicanery and underhanded business practices—too many to enumerate here—Goodman nevertheless oversaw and made crucial creative and business decisions about the Marvel Comics line that shepherded it from out of nowhere to overtake lumbering industry giant DC Comics within a decade, the comic book history equivalent of the moon landing.

—

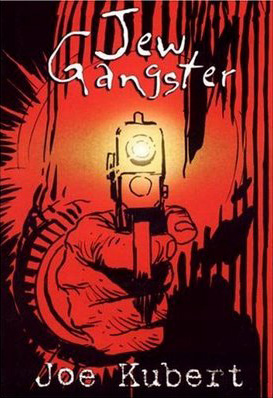

Joe Kubert

Joe Kubert (1926-2012) was born in a shtetl in Poland; two months later his family emigrated to Brooklyn. Kubert entered the comic-book field in the 1940s as a teenager drawing for DC Comics, then went on, in the ’60s, to become one of the giants of the medium, an artist whose style was unmistakable—and unforgettable. He was the most expressive pen-and-brush comic-book artist of his generation.

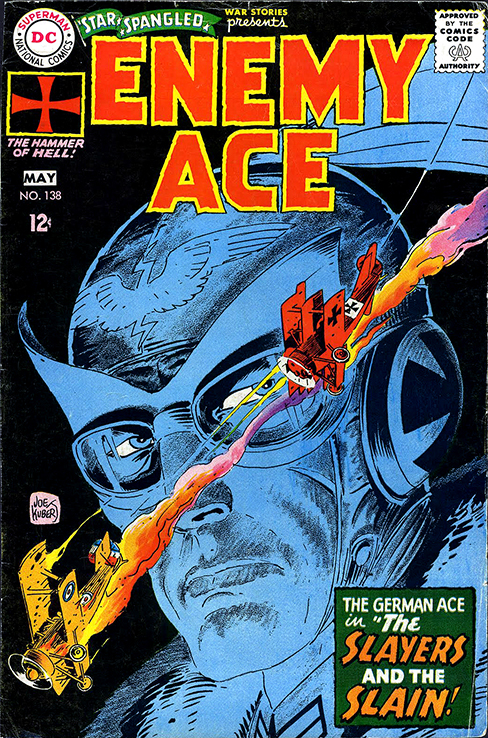

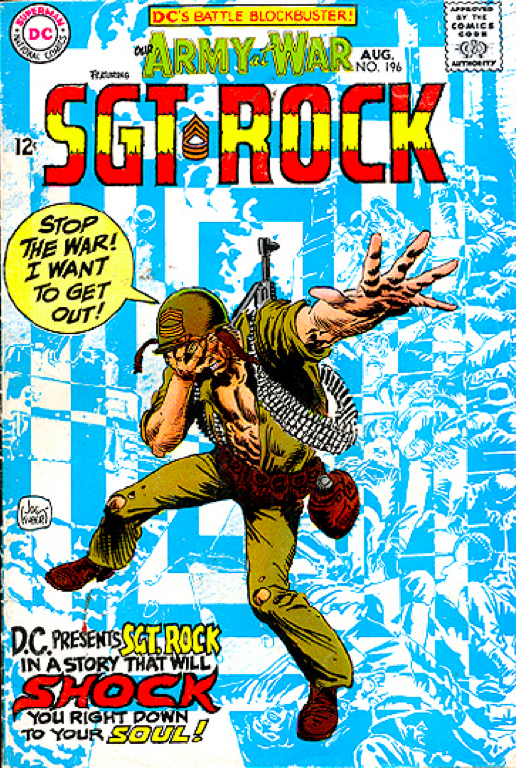

His renditions of so many DC characters have become icons that no other subsequent artist has bettered: Viking Prince, Sgt. Rock, Hawkman, Enemy Ace and Ragman. And his Tarzan is arguably the greatest rendition of the character in ANY medium.

He maintained a connection with his Jewish heritage throughout his long and illustrious career. His Sgt. Rock stories, done in collaboration with his professional soulmate, writer/editor Bob Kanigher (also Jewish), had a heightened dramatic realism, a fatalistic, moralistic Jewish attitude that rendered them, if not quite anti-war, certainly “War is Hell” or “Make War No More” (the adage they closed their Vietnam-era stories with). Their 1964 creation, Enemy Ace, dared to look at war through the enemy’s eyes, expressing a very politically left-wing, Jewish sensibility. And Ragman was an overtly Jewish superhero, born out of the rag (schmatte in Yiddish) trade in New York City’s garment center that Kubert and Kanigher were familiar with growing up.

But it was in many of Kubert’s solo works in the last stage of his career that his Jewishness took center stage: the graphic novels Yossel (2003), about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising told from the perspective of a Joe Kubert who had not emigrated to America; Jew Gangster (2005), reflecting Kubert’s experiences with the seedy underbelly of the Brooklyn he grew up in; and a comic strip, “The Adventures of Yaakov and Yosef,” for The Moshiach Times, a children’s magazine published by the Chabad Lubavitch Hasidic movement.

In 1976, Kubert founded, with his wife, Muriel, The Kubert School, an art school in Dover, N.J., that has turned out a new generation of artists that now reads like a Who’s Who of the comic book industry—including two of Kubert’s own sons, Andy and Adam. What more could you want from a Jewish patriarch?

—

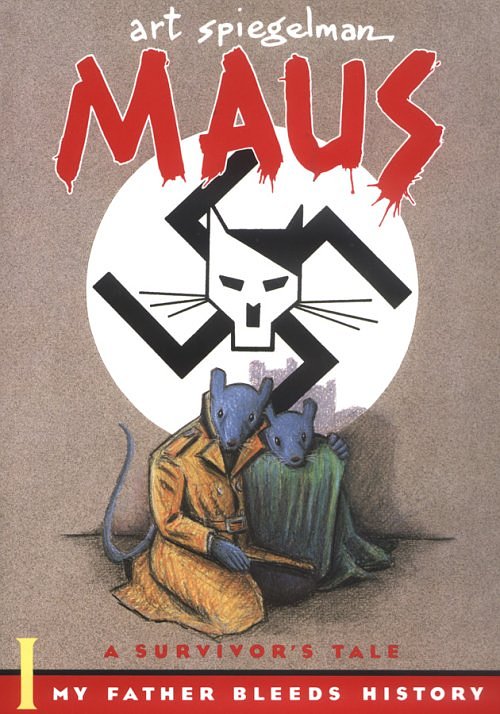

Art Spiegelman (nee Itzhak Avraham ben Zeev)

(Born in Sweden,1948.) If all Art Spiegelman ever did in his under-and-above-ground comics career was the groundbreaking graphic novel Maus (1986, ‘92), his place in the comic-book book Hall of Fame would still be assured.

Equally steeped in high and low cultural traditions, from Orwell’s Animal Farm to Disney and Fleischer Studio cartoons, as well as the ’60s San Francisco underground comix school that Spiegelman came out of, Maus brilliantly transmogrified the European Jews of the Holocaust into mice, and the Nazis into the cats that preyed on them.

Wrapping the graphic novel around first-person recollections from Spiegelman’s Holocaust survivor father added a whole other rich layer to the dense work, deserving of the special Pulitzer Prize it won in 1992. Maus has assumed its place as one of the most inspiring and influential graphic novels of the 20th century.

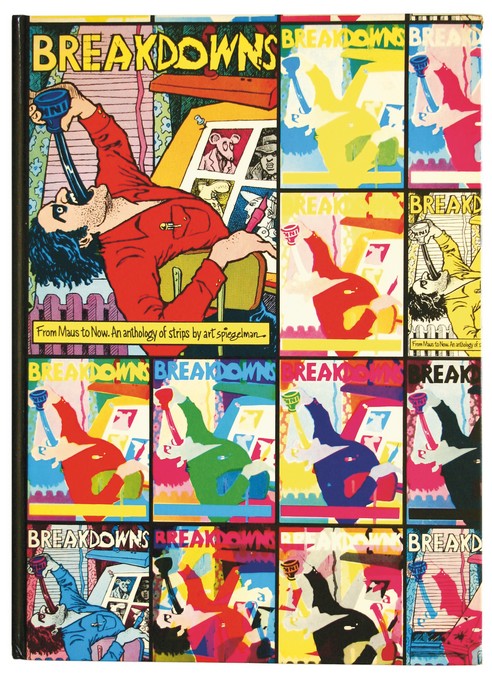

But Spiegelman did indeed do other great comics works, both before, in underground comix, and after Maus, in various books, magazines and multimedia exhibits and presentations, that are worthy of study and acclaim. Many of the best “before” works are collected in the beautifully printed and designed hardcover collection Breakdowns (1977).

—

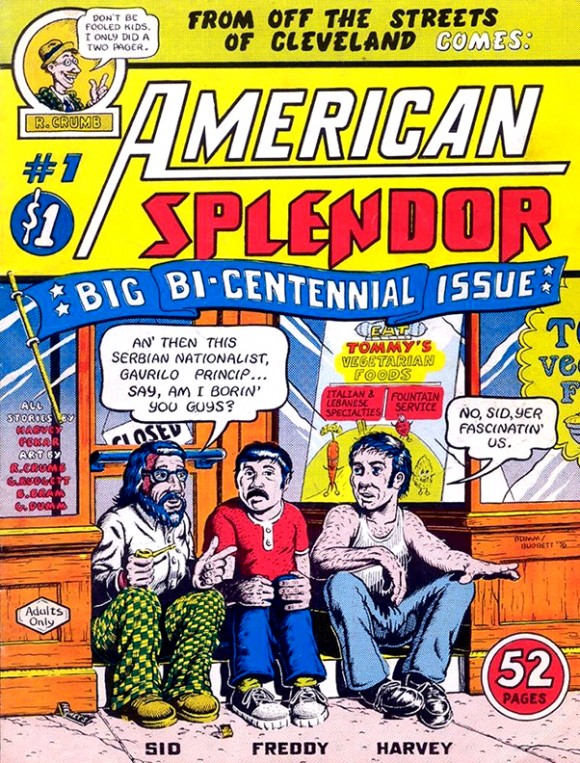

Harvey Pekar

Harvey Pekar (1939-2010) was born in Cleveland, the son of immigrant Jewish parents from Bialystock, Poland; his father Saul was a Talmudic scholar, who owned a grocery store in Cleveland that they iived above.

As a child, Pekar’s first language was Yiddish, and he learned to read and appreciate novels in the language—a background that would serve him well later in life, when he became a kind of Jewish proletariat poet/storyteller for the common, American man (who read comics).

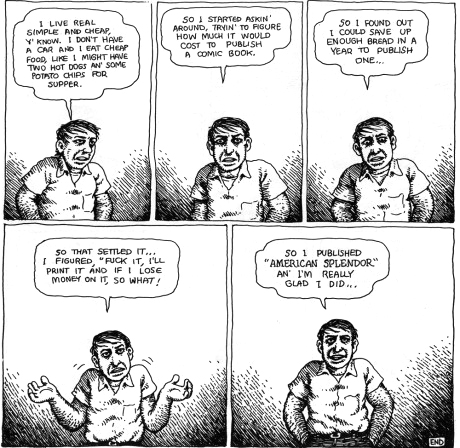

Pekar’s first-person stories were first published in the bicentennial year of 1976, and appropriately titled American Splendor, a riff on the deterioration he saw in society’s morals and lifestyle, through the prism of his Cleveland surroundings, at work and at home.

Pekar utilized a variety of artists every issue to illustrate his stories, including the great Robert Crumb, whose early participation in Pekar’s publishing foray put Splendor, and Pekar himself, on the pop cultural map. Crumb would contribute covers and interiors throughout the title’s run.

Pekar parlayed the early success of Splendor into appearances on the David Letterman show in the 1980s, and eventually a 2003 American Splendor film based on his work and life that appeared to great critical and popular acclaim.

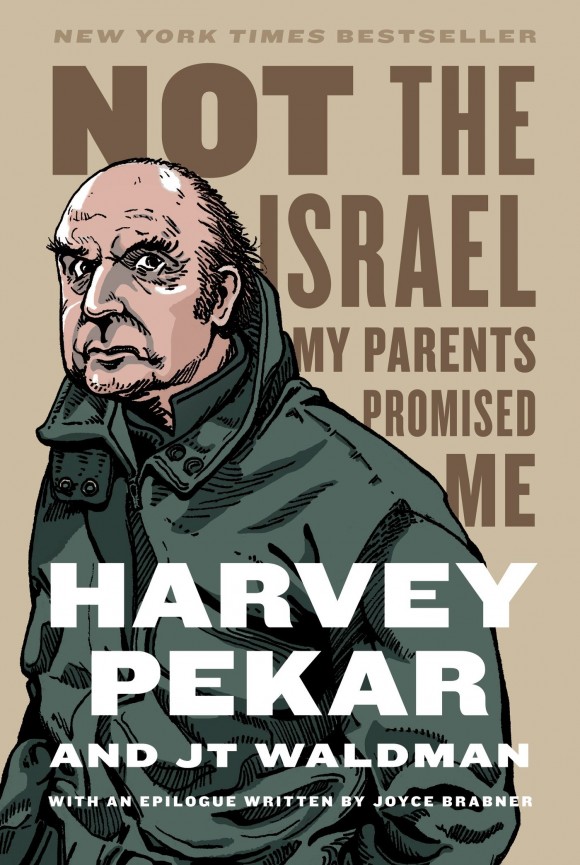

Pekar’s published comic works and graphic novels are wide and varied, from non-fiction histories like 2009’s The Beats to Jewish-centric works like 2011’s

Yiddishkeit, which depicted many aspects of Yiddish language and culture, to one of his last graphic novels, published posthumously in 2014, Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, illustrated by the Jewish artist JT Waldman (Megillat Esther, 2005).

October 18, 2023

Wow! Thank you for this! I am just discovering this in October of 2023, as war is erupting in Israel. Hate never seems to end, does it?