BATMAN ’89 ANNIVERSARY: The screenwriter reveals the fate of the Boy Wonder…

—

UPDATED 2/17/21: With the Batman ’89 comic coming in July from DC — click here for all the details — it seemed like the perfect time to re-present this piece from 2019. Dig it. — Dan

—

It’s BATMAN ’89 WEEK! Tim Burton’s groundbreaking Batman was released June 23, 1989. All this week, we’re publishing a series of retrospectives and celebrations spotlighting various aspects of a movie that was less a film and more a pop-culture phenomenon. Click here for the complete index of features.

—

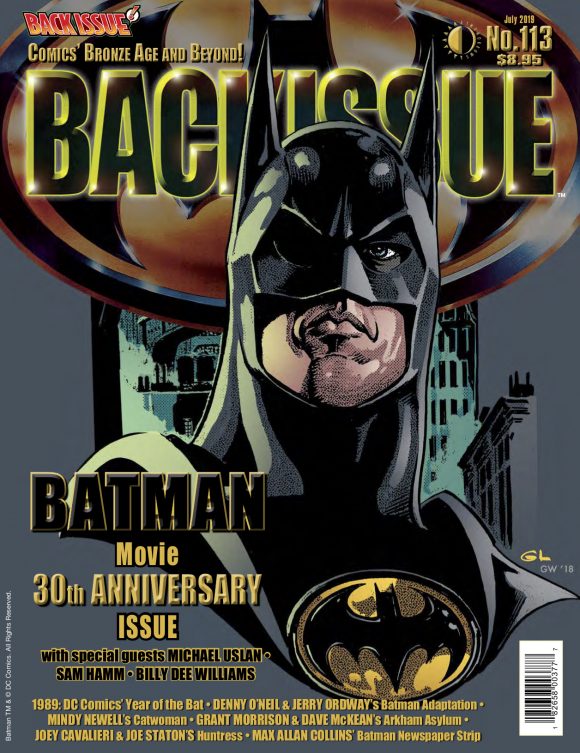

If you want to check out a really terrific new resource on Batman ’89, pick up Back Issue #113, out now from TwoMorrows.

A few weeks back, in fact, we ran an excerpt from Michael Kronenberg’s interview with Sam Hamm in which the Batman co-screenwriter cited the comics he says inspired his script.

So now, for BATMAN ’89 WEEK, we’re back with another slice – a look at why Robin didn’t make the final cut.

Again, this is just a tiny bit of what’s in the entire issue, so by all means pick it up at your local comics shop or directly through TwoMorrows. (Click here.)

—

By MICHAEL KRONENBERG

Michael Kronenberg: The biggest differences between your script and the finished film: Jack Napier is not the Waynes’ killer, Alfred does not betray Batman’s secret identity, there’s a much higher body count in your script, Alexander Knox dies, and Dick Grayson is introduced and becomes a key part of the story. Too bad the final film did not follow your script when it came to Batman’s origin and Vicki Vale discovering Batman’s identity. What did you think of these changes?

Sam Hamm: One of my mentors in the film business warned me not to argue with success, and so I guess it’s bad form to agree with you, but I do: The script was reworked by Diverse Hands, and it shows. In the finished film there are a lot of setups without punchlines, and punchlines without setups. Most of the problems derive from the decision to pin the murder of Bruce’s parents on the Joker—it changes the whole emotional dynamic between Bruce and Vicki.

The Case of the Disappearing Robin is high comedy. Tim (Burton) and I had worked out a plotline that did not include the Boy Wonder, whom we both regarded as an unnecessary intrusion. Really: Our hero was crazy to begin with. Did he have to prove it by enlisting a pimply adolescent to help him fight crime? Was Bat-Baby unavailable?

But the studio was insistent: There was no such thing as solo Batman, there was only Batman and Robin. So, after holding off the executives for as long as we could, Tim and I realized we had better try to accommodate them. He flew up to my house in San Francisco and we walked around in circles for two days, finally deciding that there was no way to shoehorn Robin into our story.

On Sunday morning at 11 a.m. we were supposed to call the studio and check in with the bad news. Fifteen minutes before that call, at the apex of our misery, we decided to try one last circuit of the carpet as a gesture of good faith. And presto! With a gun to our heads we improvised a pretty good intro for Robin. It was a self-contained sequence, building on plot elements we had already introduced, and it allowed us to shove the kid off to one side in short order. We figured that if we managed to squeeze him in, the lame hacks who were making the sequel could worry about what to do with him next.

The sequence we invented was big and expensive and, if I do say so, highly amusing. Bruce visits Vicki in her apartment to discuss his double life; the Joker shows up uninvited and abducts Vicki. Bruce, sans costume, pulls a ski mask out of a dresser drawer and follows the Joker’s van by jumping from roof to roof. He eventually horse-jacks a mounted policeman’s ride and arranges a rendezvous with Alfred, who speeds up a side street in his yellow Volkswagen to deliver the Batsuit.

A few moments later, the Joker looks in his rearview mirror and sees, of all things, Batman charging toward him on horseback. So he panics. He swerves into Gotham Park and, in the course of making his escape, accidentally kills the Flying Graysons, a husband-and-wife high-wire act performing as part of the Gotham Bicentennial. But… their kid survives. And he’s mad. You can fill in the rest.

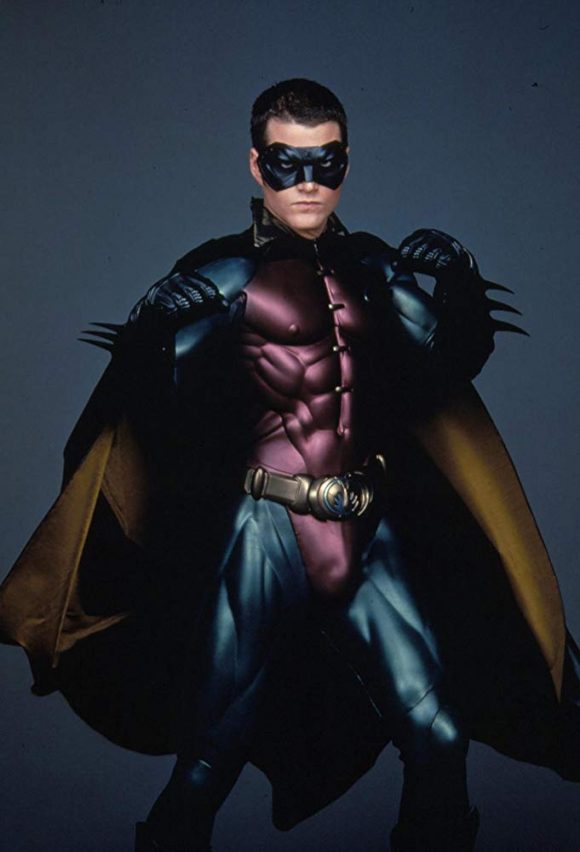

Chris O’Donnell as Robin in a publicity still for Batman Forever.

When the film went into production in London, and ran seriously over budget, WB started looking for a sequence that could be cut to save money. And there was one obvious candidate: Intro Robin!

So Robin was cut from the movie and shoved back to Batman Returns— from which he was cut yet again and shoved back to Batman Forever.

The Knox character was supposed to get killed inventing the Batsignal, which is one of the scenes I really miss. You may recall that there is a completely extraneous scene at the end of the finished film, in which the grateful police introduce the Batsignal as a means of summoning the extra-legal badass who has made them look like a bunch of feckless incompetents. Really?

—

MORE

— The Complete BATMAN ’89 WEEK Index. Click here.

— SAM HAMM: The Comic Books That Inspired BATMAN ’89. Click here.

June 26, 2019

Was Knox’s Batsignal-related demise the visual inspiration for the Carmine Falcone Batsignal in Batman Begins?

June 26, 2019

Funny interview.

I personally love Robin as a comic book character and, as the first sidekick, he is one of the most important characters in comic book history. And his character works just fine in an animated universe or in a Batman 66 universe. But, I have a hard time figuring out how the character would work in a “realistic” Batman. If you make him a kid, it’s child endangerment. If you make him an adult, you lose the innocence of the character. Chris O’Donnell’s Robin was ridiculous.

June 29, 2019

i agree and Chris O’Donnell ruins everything

June 26, 2019

As I understand it, Robin was originally created to make Batman…”softer” or more human and to give young male readers of the comic a hero they could relate to. As a preteen to teen in the 60s and 70s, I had no problem with Robin

as either a role model, sidekick, etc. But as an adult I grew to appreciate the loner Batman without Robin even more.

I began to see Robin as the goofy sidekick that Batman always had to keep an eye on, to keep safe, and therefore a dangerous distraction no matter how well trained Robin was. So when Batman 89 came out, I may have noticed that there was no Robin, but I didn’t really care. After all, the comic and this movie both had an origin that ONLY had the Batman, no Robin.

June 26, 2019

I can understand why Robin never made the cut in the ’89 film.

June 23, 2020

I always assumed it was because they didn’t really want the movie to have three origins. Batman, Robin and Joker. It’s too bad they couldn’t have the New Teen Titans era Robin and turn him into Nightwing in the sequels.

February 21, 2021

Robin can work, but only if you establish that he’s going to go after his parents’ killer on his own. Then Bruce taking him on becomes his way of protecting Dick, not endangering him. And you have to establish his athletic talent is what makes him able to not be killed. Damian makes much more sense, having been trained as an assassin. But Dick has a special place in my heart as the first sidekick.