Five decades of Sweet Christmas…

TwoMorrows’ American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1970s — by Jason Sacks and a crew of historians, including our pal and columnist Jim Beard — is back in print April 20 after eight years. Hooray! Gotta dig an in-depth, illustrated hardcover that explores the richness of the Bronze Age (or, as I like to call it, the True Golden Age.)

Anyway, we’ve got an EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT for you — the behind-the-scenes story of the creation of Luke Cage, who debuted 50 years ago in 1972.

Dig it.

—

By JASON SACKS

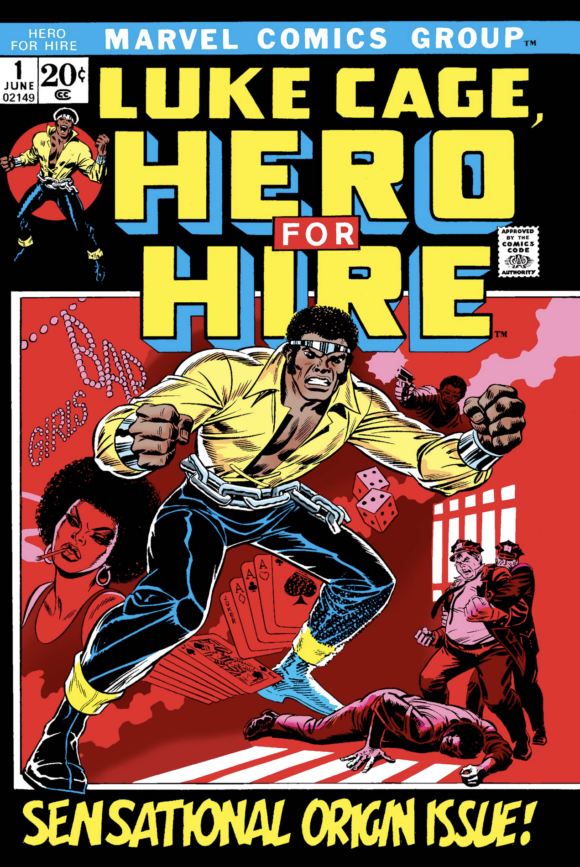

Marvel attempted to jump into another market in 1972 with the premiere of its own “Blaxploitation” character, Luke Cage, Hero For Hire. It was described at the 1971 Creation Con as “a combination of Superman and Shaft.”

The 1971 low-budget film Shaft, starring an African-American antihero, was extremely popular and influential, especially in urban centers like New York City. The movie ultimately earned $13 million against a $500,000 budget, saving MGM Studios from bankruptcy. The film triggered a boom in the genre that would soon be dubbed “Blaxploitation” by NAACP President Junius Griffin as a clever derivation of the then-popular term “sexploitation.” The Blaxploitation films were characterized by specific genre tropes: strong male or female leads, an intense metropolitan environment, and a concentration on law and order along with a contemporary funk soundtrack.

Before the Blaxploitation genre swept movie theaters nationwide, spawning black gangster films (Hit Man), black horror films (Blacula) and even direct imitations of Shaft (Super Fly), Stan Lee decided it was finally the right time for Marvel to release a comic he had long hoped to publish, one that featured a black superhero as its main character. The prospect of a comic starring the Black Panther, an African king, had previously been dismissed for a number of reasons, including the unfortunate similarity in names that the Panther had with a radical political group that had gained notoriety in the late 1960s.

But with the success of Shaft, Lee plunged ahead with the idea for a new Black superhero, consulting with Roy Thomas. Journeyman Archie Goodwin was brought onboard to write the series. Though white himself, Goodwin had written a number of comics that featured African-American lead characters for Warren Magazines and other publishers. In addition, Goodwin brought an attitude to the book that was different from many of Marvel’s other writers.

John Romita

As the man known only as Lucas is introduced in Luke Cage, Hero for Hire #1 (publication date June 1972), he is a prisoner in corrupt Seagate Prison, sometimes called “Little Alcatraz” by its inmates. Continually condemned to solitary confinement because of his attitude and refusal to get along with either the vicious guards or venal prisoners, Lucas is an outsider in a place that doesn’t tolerate outsiders. Led by the sadistic Rakham, the guards beat Lucas in an attempt to get him to get along with others, but the beatings only make Lucas more defiant.

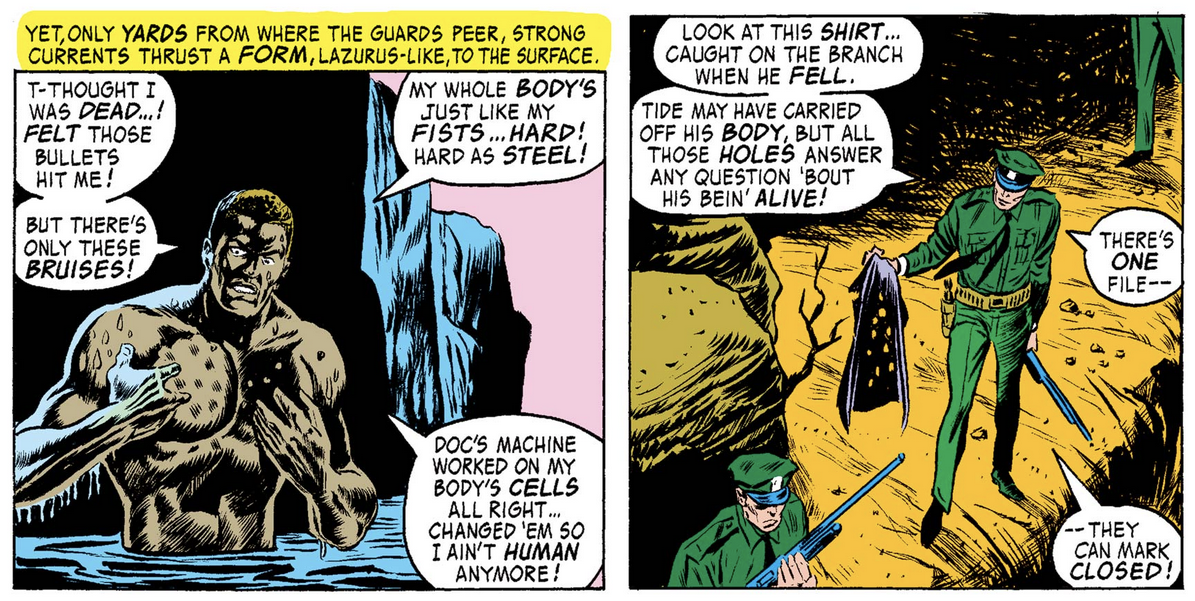

As the story unfolds, readers discover that Lucas has been framed by a childhood friend for the crime that sent him to prison. Lucas has created his own share of trouble, but he’s innocent of the charges for which his old friend Willis set him up. As a result, Lucas is desperate to get out and clear his name, so he volunteers for a risky medical experiment that will cure major diseases.

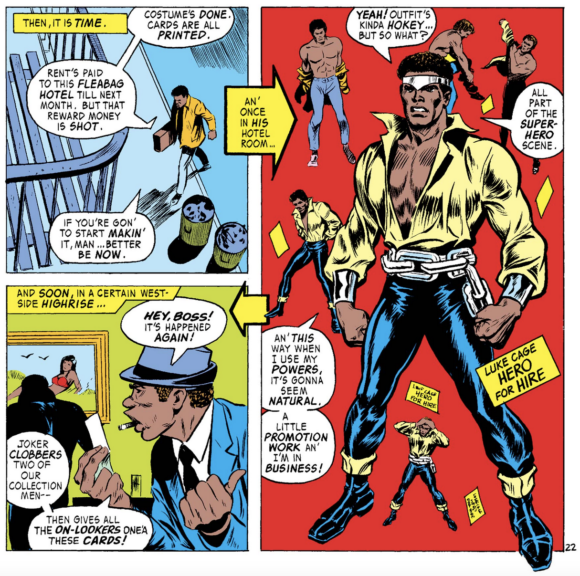

If Lucas participates in the experiment, it may result in his parole. However, the experiment backfires, thanks to Rackham’s sabotage. Lucas gets a super-dose of the drugs, which give him tremendous strength and offers him the possibility to escape prison. Breaking down a prison wall and jumping into the surrounding river as bullets litter the water, Lucas swims away from Seagate and eventually finds himself back in Harlem. There he dons a blue and gold costume with a belt made out of chains, takes the name Luke Cage, and sets himself up as a freelance “Hero for Hire” who can redeem his name at the same time he earns an honest buck.

It was Roy Thomas who contributed the name “Cage” and the title Hero for Hire. In an interview for American Comic Book Chronicles, Thomas reports:

“Stan didn’t want a typical superhero name for the comic, but wanted him to want to make a pay-ing career of crime-busting, and was looking for a title. I had some months ago written an Avengers issue called “Heroes for Hire,” so I suggested Hero for Hire. Stan also wanted a good one-word name for him that was atypical, and I suggested “Cage.” It was only later… when it was too late to rescind… that I realized I had subconsciously taken that name from a list of hero names that Gil Kane had shown me some time before (the name “Chane,” which he later used for a sword-and-sorcery hero, was also on that list). I apologized to Gil for that, but he said not to worry about it… there were plenty more names out there.”

As far as the level of Cage’s powers, Thomas based them on Philip Wylie’s classic novel Gladiator. While Cage couldn’t perform superhuman leaps like Gladiator’s main character, he could withstand bullets. In order to fit his ground-level purview, Cage would be powerful but not too powerful. Larger weapons, for instance, could hurt him. Cage was strong but not nearly as mighty as the Thing or the Hulk.

John Romita designed Luke Cage’s costume, with a bit of supervision from Lee and Thomas. One of Romita’s flourishes was Cage’s chain belt, which was meant to be a reflection of his origin story. Thomas assigned the pencil chores for the book to longtime cartoonist George Tuska (who had drawn street-crime stories in the 1940s and ’50s Crime Does Not Pay) while adding African-American Billy Graham as inker.

As Thomas reflects, “Billy Graham was brought in to ink, and was instructed to make certain that George’s African-American characters looked African-American; I think there was always the idea in my mind, probably Archie’s and John’s as well, that Billy, a talented artist who was still developing, might take over the penciling at some later stage when George was moved on to other things.”

Though the series was never a huge hit, Hero for Hire was strategically significant to the Marvel line; in a 1972 internal company memo listing Marvel’s most important characters, Luke Cage received the highest rating for marketing potential, along with Spider-Man, the Hulk, Conan, Ka-Zar, Dr. Strange and the Silver Surfer.

—

American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1970s, a 288-page, full-color hardcover, is due April 20 and lists for $48.95. It will be available at comics shops and booksellers but you can also order it directly from TwoMorrows. (Click here.)

—

MORE

— From GOLIATH TO LUKE CAGE: Classic Black Superheroes Get Much Deserved Spotlight. Click here.

— LUKE CAGE to Get First Solo EPIC COLLECTION. Click here.

April 15, 2022

Happy 50th anniversary to the Luke Cage character.

April 15, 2022

I loved that series! More realistic and gritty than traditional superhero fare. I could see him running with DD, up against the crime bosses, etc.

April 15, 2022

Very cool column. I’ve always loved “Power Man”, which is what I initially knew him as in the early 80s.