A story obscured by the mists of time…

The early days of comics are often murky, with claims and counterclaims of who created what and whom. The whole issue of Batman, Bob Kane, Bill Finger and Jerry Robinson, for just one prominent example, took decades to sort out and even now there are still some lingering questions.

Enter the late artist Frank Foster and a claim that he created Batman — or at least a version of him — a full seven years before Bruce Wayne entered the collective consciousness in 1939.

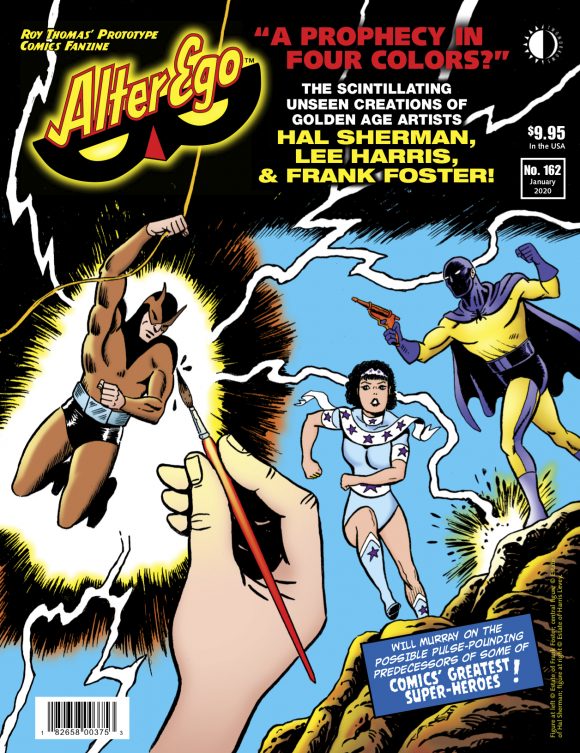

The story is included in Roy Thomas’ new Alter Ego #162, which, among other things, looks at superheroes who were created well before their better-known versions saw print.

Was it bad timing? Was there chicanery? It’s hard to say, but in the issue, historian Will Murray tries to make sense of it all — and we’ve got an EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT below focusing on Foster’s earlier, noncaped crusader.

But first check out the issue’s table of contents, which shows what other historical goodies are in store for you:

—

So let’s get to the mystery of the first (?) Batman — and a stunningly early use of the term “Night-wing.”

This is actually a fairly brief (and somewhat edited) excerpt, so by all means, pick up the issue, which is already available at some comics shops and can also be ordered directly through publisher TwoMorrows (click here):

—

By WILL MURRAY

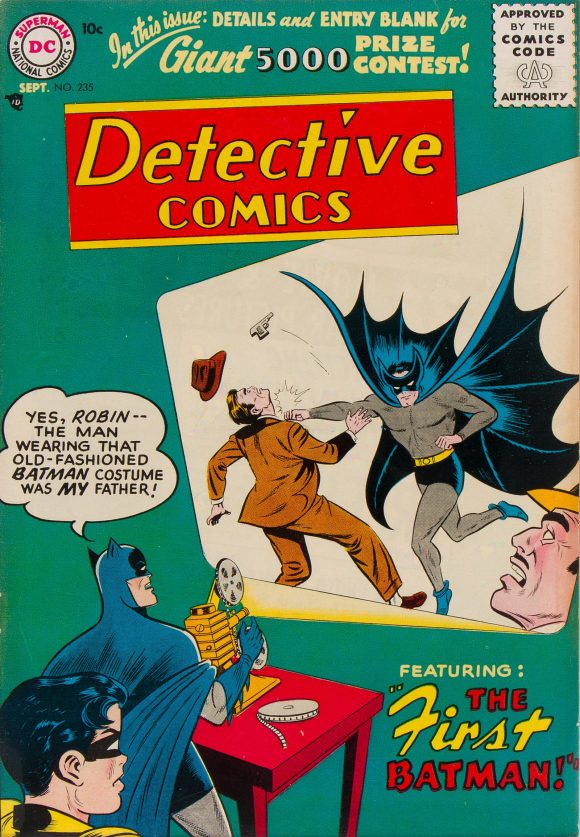

One of the most famous Batman stories, The First Batman (Detective Comics #235, Sept. 1956), related the tale of Bruce Wayne’s astonishing discovery that his father had once worn a bat-costume similar to his own to a masquerade ball. It was an electrifying moment in the life of the Caped Crusader—the revelation that he was not the first Batman.

Frank Foster Jr. knows how Bruce Wayne must have felt.

ImgIsCanon:UserID=joseh:Machine=2UA3390QWS:APP=ISAS_Acquire:Version=1.4.0.0

His own father, he believes, created the original Batman—10 years before Bob Kane’s version debuted in Detective Comics #27. Interviewed in the cool comfort of his Cape Cod basement home office, surrounded by his father’s nautical watercolors, Foster, a retired commercial photographer, recalls first hearing about the prototypal Batman when he was 4 years old in 1940.

“I remember my parents telling me about it before I ever saw the Batman comic. My father said he drew the Batman and showed me the drawings. He said he showed it to people in New York, and they stole his ideas and he never got a penny.”

It’s an amazing, even stunning claim, that contradicts the admittedly murky lore surrounding the origin of the Caped Crusader, who debuted in early 1939.

“A father does not tell his 4-year-old child that he’s been cheated!” Foster says firmly. “It was a curious thing for me when I was a kid. Not of any great significance, particularly. When I was of comicbook age, I’d say, ‘My father invented Batman.’ The kids would say, ‘Oh, sure.’ The drawings were always around.”

Foster’s Batman

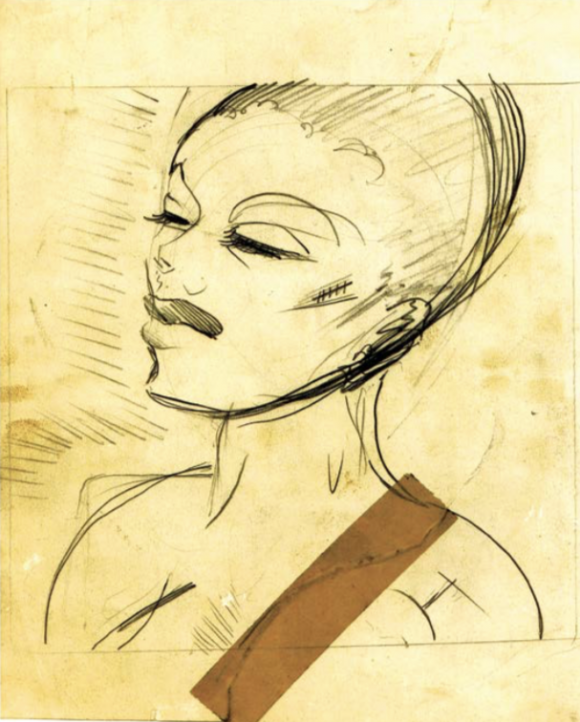

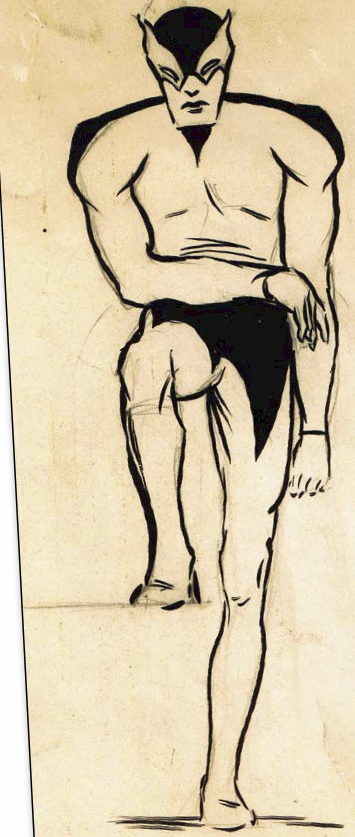

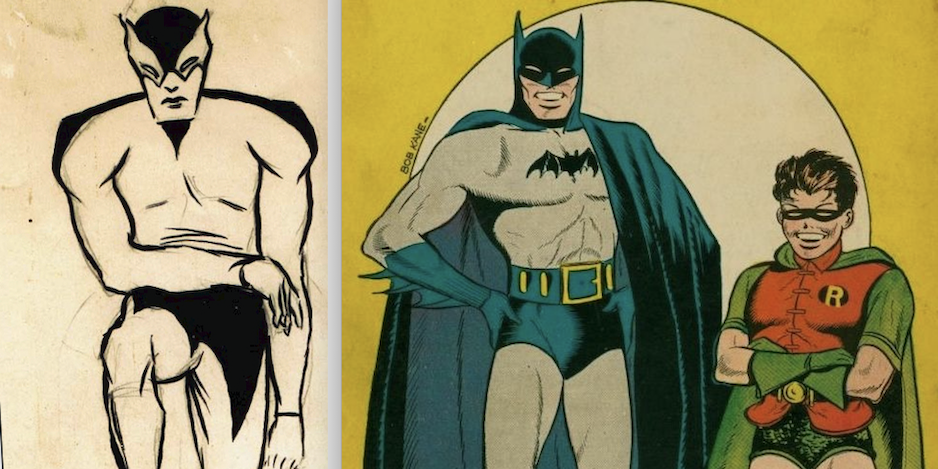

From a long architectural file drawer, he pulls out the original concept drawings to what his family has always believed is the one, true, original Batman. The ancient piece of Strathmore board is yellowed, its edges chipped by time.

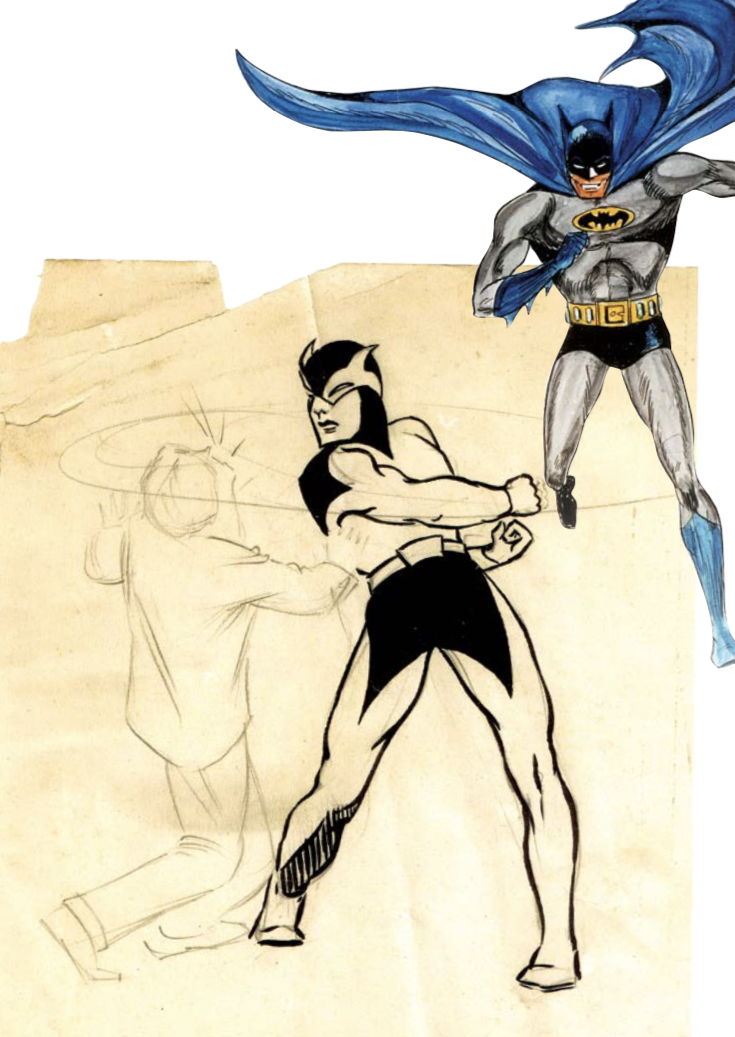

Across the front are three India ink shots of a character caparisoned in a strikingly stylized super-hero costume: in action, decking a lightly penciled figure with a roundhouse right cross; standing in a nonchalant pose with one arm resting on a casually lifted leg; and climbing in through a window in classic super-hero style.

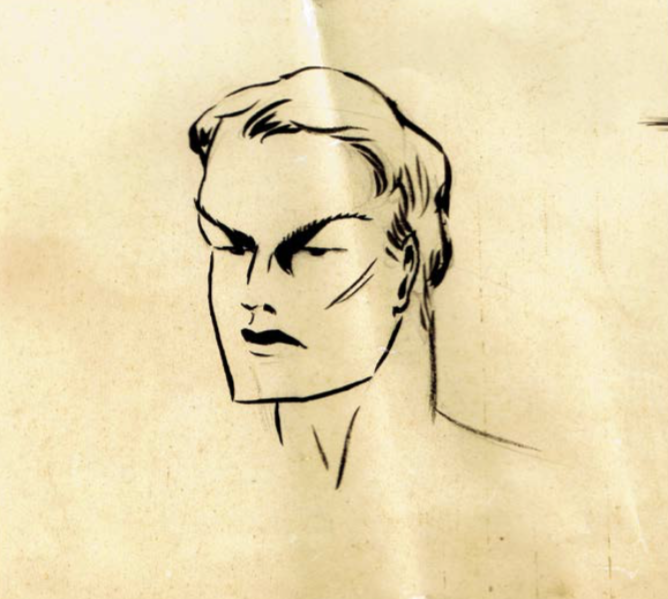

And below that, a three-quarters-view head shot of the unmasked mystery-man with a strangely batlike left ear and a sharp jawline that smacks of both the Golden Age Batman and Dick Tracy!

Foster flips the board to the other side to reveal a pencil sketch of an exotic-featured woman. The words “1932 Village” are visible and below that, two startling names in bold script:

Batman

Night-wing

Asked about the significance of these names, Foster digs out a deposition his father gave in 1975 and indicates the explanation Frank Foster Sr. offered at that time:

“Oh, I guess that was a night wing, or something like that…. That’s just some sort of alternate thought I had at the moment, and then I checked off Batman because I thought that was a better name.”

Foster, Jr., seemed oblivious to the electrifying significance of the second name. Nightwing was the name a grown-up Robin would take in 1984 for his adult crime-fighting alter ego during his stint with The New Teen Titans. Twenty years before that, it had been Clark Kent’s secret identity in the bottle city of Kandor.

According to Martin Cruz Smith’s 1977 novel Nightwing, it’s a translation of the Navajo word for “bat.”

At first glance, it might seem the notation “1932 Village” refers to this drawing, as if she were some unusual woman Foster sketched from life in Greenwich Village in New York City. Frank Foster’s deposition is silent on her significance. But Frank Jr., recalls this: “My father told me that was Batman’s girlfriend.” Pressed for more details, he admits not being sure his father meant girlfriend in the literal sense. “I know it was related to Batman,” he says. “She was an exotic character in his life.”

The art is unmistakably faithful to the period, and the Strathmore board and ink have been authenticated as pre-World War II. The Batman drawings are rendered on the “tooth” side of the board, indicating the art dates back to at least 1932, if not before.

Could this be true? Could an obscure aspiring cartoonist have created a comics-style Batman before Bob Kane and Bill Finger conceived the Caped Crusader in 1939, and prefigured even the name of Nightwing?

The story of Frank Dinsmore Foster Sr.—who died in 1995— and his Batman is a fascinating and intriguing one. It might have been lost forever except for his son’s determination. In 1975, inspired by a newspaper story about longtime Batman artist Lew Sayre Schwartz, he persuaded a reluctant Frank Sr., to see a Boston law firm in an effort to explore possible legal remedies.

“I didn’t push him,” the son recalls. “We made him come rup to deal with my company attorney at Shapiro & Israel. I said, ‘Everyone’s fascinated when you tell them the story—at first.’ But when they say, ‘Well, what are we going to do with this?’ They agreed to give it a little bit of a run. And so my father came up—at my insistence. It wasn’t that he didn’t want to do it. My parents gave up on this many, many years ago. They were too busy trying to put food on the table. But then they had the Batman television series, and all that stuff.”

Foster’s Batman, along with a latter-day illustration by Bob Kane

The elder Foster’s saga begins in the late 1920s when he was an aspiring young musician attending the Designer’s Art School in Boston.

“And at that school I became very friendly with Al Capp,” Foster Sr., told his lawyers in 1975. “We went to school together and were quite close. I was studying fine arts—I was only interested in fine arts, and Al has always been interested in comics, and he asked me at one point during our school days if I would be the artist for a strip if he sold it. And I had no interest in it. But he talked me into a partial interest.”

Foster recalled coming to New York circa 1931 after going to art school with Capp. Capp dropped out of art school and went to New York, where he started Mr. Gilfeather, a daily panel for The Associated Press, in 1932. Before long, he was assisting Ham Fischer on Joe Palooka, then jumped ship to create Li’l Abner in 1934.

It was during this period that Foster remembered conceiving his Batman—and another super-heroic character, the Raven.

“He got me interested enough to make some ideas up. And it seems to me that in those days, and even now, that most of the strips were heroes of the day—such as flying through the sky during the day and doing good deeds and so forth and so on—and I thought, well, why couldn’t that be done at night?”

Foster’s Batman — unmasked

—

According to a statement by Foster’s wife, Ruth, “I met Frank in 1927 while he was studying art at Designer’s Art School in Boston. We were married on July 15, 1932, the year after finishing his studies. It was most likely that the original drawings of ‘BATMAN’ were executed during the latter part of his attendance at Art School (1930-31), as I know they were done before our marriage.”

According to Frank Foster’s own recollection, he traveled from Boston to the Greenwich Village section of New York City in 1931 or ’32, and showed his ideas around with no result.

Ruth Foster adds: “All of his drawings were put aside from 1932 to September 1937, during which time all of his efforts were made in trying to support me and our son, who was born on December 25, 1935. His business failed, and in September 1937 we moved to New York City, where he had some periodical work in his brother’s painting and decorating business. The following three years from September 1937 to October 1940 were financially grim years. (The Depression at its worst—particularly for an unknown freelance artist). From October 1938 to October 1940 we lived in Christopher Street in Greenwich Village.”

It was during this period that Frank Foster Sr. tried to sell his services—and Batman and his other hero, the Raven—in earnest.

—

(NOTE from Dan: Again, to no avail. Foster’s attempts took a circuitous route through the world of New York publishers.)

One of the problems was that Frank Foster remembered showing his portfolio all over New York, but except for (an experience with the Frank A. Munsey company), couldn’t specifically recall which companies he had visited. His son, who researched the period, points out that in 1937, his parents lived on East 52nd Street in Manhattan — only five or six blocks away from the DC Comics offices on Lexington Avenue, between East 46th and East 47th Streets.

“In my opinion,” he says, “if he went to New York to sell his art, he wouldn’t have missed them. He was right next door to them. I think the chance that he overlooked them is nil. Considering that’s what he went for, and there were so few places to go anyway.”

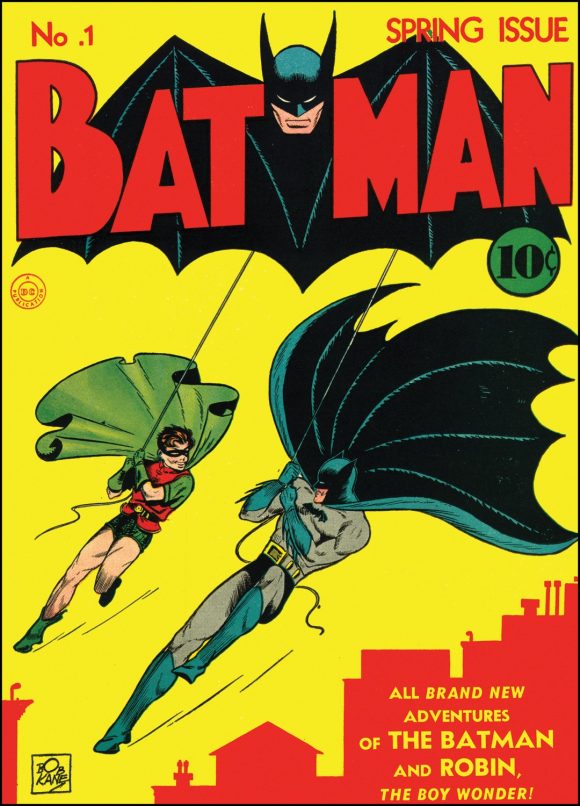

(Frank Foster recalled) discovering Batman comics in Washington in 1940. Not being a comics reader, he could have walked past Detective Comics without noticing a vaguely familiar creature of the night all through 1939. But the logo on the eponymous Batman comic would have shouted out to him from any newsstand. Batman #1 debuted with a Spring 1940 cover date.

As far as the son knows, there are no scripts or notes or other art to shed any more light on the Batman of 1932. So we will never know who the rock-jawed face beneath the cowl really was, or how he came to be.

—

Alter Ego #162 is already available at some comics shops. It can also be ordered directly through publisher TwoMorrows. Click here.

—

MORE

— The TOP 13 GREATEST BATMAN STORIES EVER — RANKED. Click here.

— Why the BATMAN #1 TREASURY Is an Enduring Classic. Click here.

November 30, 2019

It’s a lot to swallow. First we have to believe that Foster came up with the *entire concept* of the masked hero wearing a tight-fitting circus costume in 1932 — BEFORE Lee Falk’s Phantom, before The Shadow, before Flash Gordon. And he thought the company that later became DC Comics stole his idea? When the predecessor to that company didn’t even exist as a glimmer in the eye of Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson in 1932? No, I don’t think so. Even IF the drawings could be positively validated in terms of dating, they were never published. You think editors or publishers remember every single submission that they ever saw?

Better to focus on the connection between Whitney Ellsworth, DC editor at the time Detective Comics #27 was published, and his former employer, Better/Standard Publications, who published the pulp magazine Black Book Detective, which featured the Black Bat, a month or so after Batman premiered, but had published a different Black Bat character (back when Ellsworth still worked for them) a few years earlier.

December 3, 2019

1. The Shadow debuted on radio in 1930, and 1931 in print, so Foster’s Batman didn’t precede him. 2. Why don’t you say, “Did Lee Falk steal his idea for the Phantom? before him, there weren’t any!” 3. The date of the art has been authenticated. The thornier issue is one of theft. I don’t believe the idea was stolen. He wasn’t shopping it around in the late ’30s, and the length of time passed was too long. Vampires were in a big thing in the early ’30s, so such a character shouldn’t be a surprise. There are a few bat characters in the pulps, too.

November 30, 2019

Knowing what we have known for a few decades now about Bob Kane and Bill Finger, does it really surprise anyone that Kane may have copied “his idea” from someone else? I will still give Kane a little praise for bring the concept to life with a LOT of help from the more talented Finger, but my skepticism over Kane’s creativity will always remain.

December 1, 2019

Well, there’s a lot of years (seven to be exact) between Foster’s 1932 Batman and Kane’s 1939 Batman. So how do you figure it, Foster was schlepping those drawings around from publisher to publisher for 7 years, or that Kane deemed 7 years a reasonable amount of time to wait before swiping someone else’s idea? Given some reasonable cause to believe that Kane had some contact (directly or through Ellsworth) with Foster prior to 1939, I wouldn’t doubt he’d borrow whatever he saw fit to, but it’s more a question of opportunity than motive.