Rich Handley looks at the Caesar-Thade smackdown that might have been!You can find earlier installments on Marvel here, Malibu here and Dark Horse (and Spanish-language comics) here.

By RICH HANDLEY

MR. COMICS

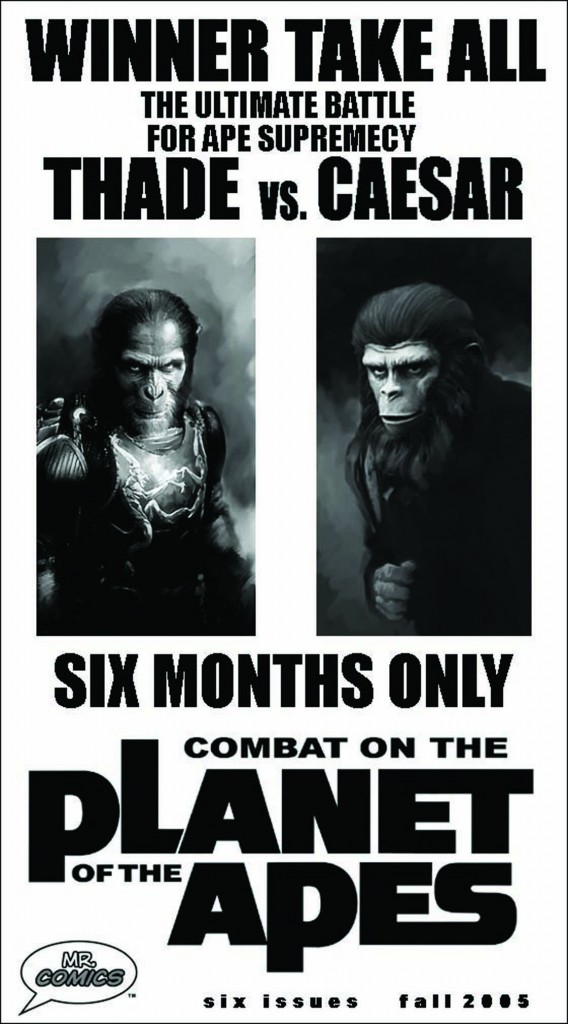

Combat on the Planet of the Apes

Metallic Rose (Mr. Comics) raised the bar on “Planet of the Apes” comics when it published its highly lauded miniseries Revolution on the Planet of the Apes, written by Ty Templeton and Joe O’Brien. However, Templeton’s original script, titled Combat on the Planet of the Apes (alternate title: War on the Planet of the Apes), was quite different.

In his script for Combat, Templeton says, Thade and Caesar would have co-existed on the same Earth. “There’s nothing in the Burton movie,” he maintains, “that rules out the original films, since all of his movie takes place on another planet that is not Earth, until the very end when we discover Earth has been taken over by Thade’s followers, years in the past, because of a time loop.” (It should be noted that the opening scenes would seem to negate the original films, since Earth is not yet ape-dominated, even though the film opens in 2029, almost 40 years after Caesar’s 1991 revolution.)

Had Combat seen print, Templeton would have revealed Thade’s apes to have been an offshot of Aldo’s genetically enhanced ape pilots. “There was nothing that said the Earth that Thade went back to couldn’t have been the very same Earth that Milo, Cornelius and Zira went back to,” he explains. “And, in fact, they arrived at similar times. So in our original script, the ape revolution on the West Coast, with Caesar, was going to create a small Ape Nation, leaving the rest of America ruled by humans—no nukes, no big fight for America.” In fact, Templeton says, Caesar’s apes would have attempted to live in peace with humans, as he’d promised at the end of Conquest of the Planet of the Apes.

A decade later, Templeton says, Thade would have arrived on Earth with a squad of soldiers, to discover a world with both human and ape governments, living side by side. “Thade originally lands on the East Coast,” he states, “and is taken in to see the human government, as Zira and Cornelius originally were. He eventually tires of the humans prodding him, asking questions about his ship and his story, so Thade [escapes] and makes his way to California, to meet up with Caesar, proposing to create a vast ape army and take over the world for apekind.”

Caesar would have been intrigued by Thade, Templeton says — “a creature from the future, like his parents, but from a colony world instead of Earth itself” — but would have declined the offer, preferring to keep the peace. “Thade won’t hear of it, and starts preaching violence and human hatred to the inhabitants of Ape City, eventually causing a schism of the population (mostly amongst the gorillas) who form an army and head out from the valleys into the hills of California.”

Thade’s splinter group, Templeton says, would have secured all of the state’s military installations, seizing jets, tanks, ships and other vehicles to defeat the humans still running America. “A few of the ideas made it into the miniseries anyway, with Aldo stepping into the role of Thade for the whole subplot involving the attack on the East Coast. Taking over the White House, for instance, was a scene almost intact from the original script, where Thade lights a cigar sitting in the oval office, rather than Aldo.”

The apes’ reverence for Thade would have grown with each victory against humanity, culminating in a civil war between Thade and Caesar for leadership of apekind. Caesar would have won, killing Thade but giving him a special place in history to heal the rift caused by the conflict — and, thus, explaining his statue replacing the Lincoln Memorial.

Ultimately, Templeton reveals, Thade would have become the original Lawgiver who wrote the scroll warning against “the beast, man” — a passage previously attributed to an orangutan during the Adventure Comics run, and more recently to another simian in BOOM!’s recent Apes run — and an offshoot of apekind would thereafter have revered him as the true spirit of apedom, rather than Caesar. “The legacies of Thade and Caesar become intertwined,” he says, “as the spirit of peace and war that permeate the ape adventures.”

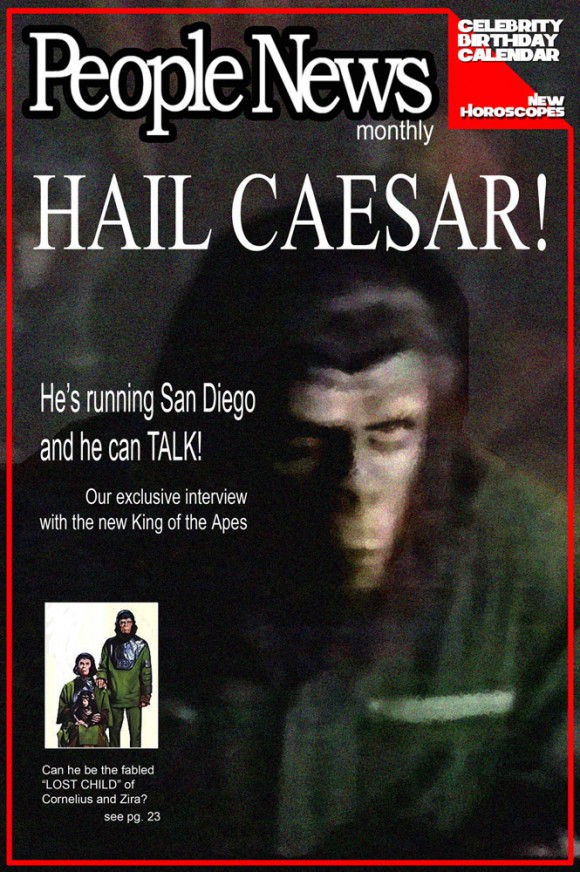

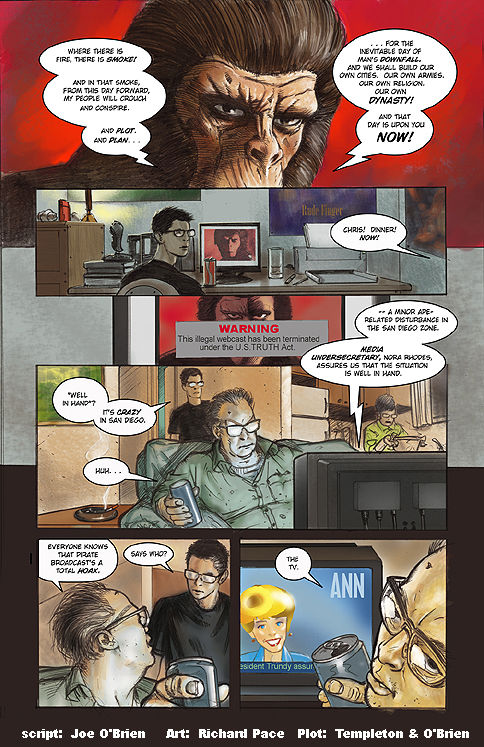

Artist Richard Pace had created a promotional poster, cover art and several interior pages for the Thade-Caesar version. In the end, however, Fox nixed such a crossover, and Templeton altered Revolution to focus on Aldo rather than Thade. “When we moved to a new storyline,” Templeton says, “Richard was too busy to work on the book, and we, sadly, had to go with other creators.” Pace’s artwork was later slated to appear in a trade-paperback compilation of the final miniseries, but Mr. Comics never released that promised collection, and so Pace’s work remains unavailable.

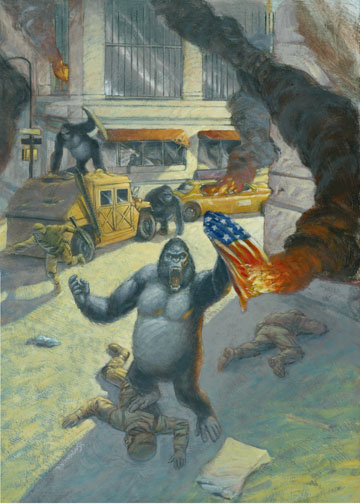

Also altered was artist Dennis Rodier’s original painted cover for Revolution #1, which 20th Century Fox rejected out of concern over its depiction of a burning U.S. flag. Templeton eventually posted the original version at his blog.

“The Believer”

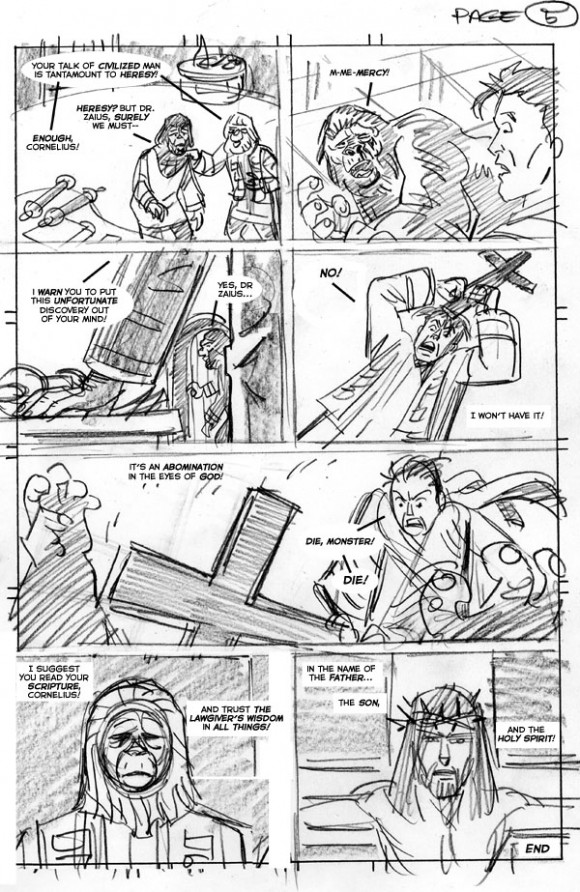

One major loss to fans due to Mr. Comics’ failure to release the trade paperback was a five-page story written and illustrated by Sam Agro, originally slated to appear as a back-up tale in Revolution issue #4. This story, titled “The Believer,” would have tied into both the miniseries and the first Apes film, featuring parallel storylines set during Caesar’s 1991 rebellion and Zaius’ revocation of Cornelius’ travel permit in 3977.

In one timeframe, while watching footage of Caesar’s revolution on the Internet, a priest prayed before his altar, stunned that any animal but man could have “the divine spark” of intelligence. The clergyman sought Christ’s guidance, wondering if he should accept speaking apes as his brothers. As he did so, a gorilla crashed into the room, but rather than embrace peace, the priest beat the beast to death with a large crucifix, ignoring its utterance of a single plea, “mercy.”

Meanwhile, in the other setting some 2,000 years later, Cornelius met with Zaius to ask why his permit had been canceled after finding a cave of artifacts. The orangutan told him he’d hoped to spare Cornelius “an exercise in futility,” for science must never supplant the Sacred Scrolls and their warnings of mankind’s danger. To that end, he urged Cornelius to put aside his discovery, re-read his scriptures and trust the Lawgiver’s wisdom.

Agro submitted fully penciled and lettered artwork to Ty Templeton for his consideration. “I did think the story was a strong one,” Agro says, “and very much in keeping with the fundamental themes of the original series of films: religion, repression, prejudice, ignorance and violence.” The use of a Catholic setting, he notes, was intentional. “I felt the Catholic religion, which leans somewhat more toward the Old Testament than some other Christian faiths, helped to set up the priest’s final choice to go all medieval on the gorilla’s ass. And, the priest is bludgeoning the ape into submission literally, whereas Zaius is pummeling Cornelius into submission verbally, with well-chosen quotations and threats of heresy.”

Templeton, however, foresaw a backlash over the religious overtones of the story—particularly the final panels, which juxtaposed the Christian and simian saviors. “In the final two panels,” Agro recalls, “I drew a direct visual comparison between the Lawgiver and Jesus. Ty felt this was a bit too ‘hot’ for our publisher, Steve Ballantyne, and probably for Fox as well. And he also felt, perhaps rightly so, that some readers might find it offensive. I think he said something along the lines of: ‘People don’t want to see their God compared to a monkey.'”

What’s more, Agro says, there was also a disagreement about the use of parallel panels, as well as the lack of action in the Zaius/Cornelius scenes. “I felt that the use of coloring — sepia tones for Zaius, and full-color for the priest section — would clarify the two continuities sufficiently to avoid confusion, and that for a five-page story, there was plenty of action in the main sequence. Plus, I liked the idea that the story could be read three ways—from beginning to end, or either continuity alone. Considering those points of contention, and the fact that I felt the story would lose about 50 percent of its punch without the direct comparison of the final two panels, I ultimately decided to pursue another idea I’d come up with earlier.” That idea was “Paternal Instinct,” which appeared in its place as a back-up tale in Revolution issue #4.

Despite his reservations at the time, Templeton highly praises the story and its author. “Planet of the Apes succeeds when it pushes the envelope,” he says, “and this is a strong story. I think it absolutely deserves to be seen by people.” In 2010, the story finally saw limited distribution in issue #16 of Simian Scrolls, a POTA fan magazine.

Empire on the Planet of the Apes

Following the first miniseries’ critical success, Templeton and O’Brien began discussing a proposed sequel, titled “Empire on the Planet of the Apes.” However, that follow-up title never came to pass for reasons unknown even to Templeton.

Had Empire been published, Templeton says, he and O’Brien intended to chronicle the building of Ape City (as seen in Battle for the Planet of the Apes), explaining how the gorillas and chimpanzees came to lead separate lives following that film, with different civilizations and separate Lawgivers — a topic briefly explored in “Ape Shall Not Kill Ape,” a backup story in Revolution issue #5. Their goal, he says, would have been to fix the “continuity glitches” they saw between the first three films.

Although Templeton kept no detailed notes outlining his plans for Empire, he does recall some of what he and O’Brien had in mind. “The schism between chimps and gorillas came from the gorillas’ wish to see all humans killed,” he says, “and the chimps wished to live with us lowly people. This was mostly because of the terrible treatment gorillas suffered before the ‘Night of the Fires.’ Chimps, bonobos and orangs were usually domestic servants, gorillas were laborers, and the memory never went away.”

Following the break-up of apes into two camps, Templeton says, orangutans and bonobos lived in both nations, as “the smart apes in society, taking over the sciences and schooling.” Sadly, he adds, “the bonobos die out in a few generations and do not survive into the 30th century — too small and gentle a race, even for the ape civilization.” (The bonobo species, though not appearing on film, was featured in “Ape Shall Not Kill Ape,” as well as in the “Burtonverse” novels “The Fall” and “Rule.”)

One of Templeton’s goals in conceiving Empire was to reconcile Aldo’s role as a hero of ape history in “Escape” with his nature as a “monstrous villain” in “Battle.” The groundwork for this reconciliation, he says, was laid with “Ape Shall Not Kill Ape,” in which an army of apes — descendants of those who left Ape City 300 years earlier to protest humanity’s place in society — returned to rewrite history. “There’s more than one history of this civilization,” he says. “It splits up at some point, to come together again. Anthropology is full of that stuff — Phoenician/Egyptian/Nubian cultures all have the same root languages and religious icons, but they clearly become different cultures at some point.”

Templeton says he might also have explored an aspect of the first two films that had always puzzled him: “I had always wondered about the lack of non-whites in Zaius’ time,” he explains. “There is something fascinating there, but it would have to be a hideous period of history that one would cringe in the reading of it. I assume they [non-whites] were hunted to extinction five hundred years back, no?”

In fact, it was the idea of non-Caucasians not living in North America that interested him most. “I always had it, in the back of my head, that there were many human colonies—survivors, mutant, semi-mutant, all sorts of different kinds of versions of ape-like creatures living on this planet. Maybe there’s a baboon colony in Spain, and who knows how the monkeys fared in South America. The brief snapshot of civilization that Taylor and Brent get is so myopic that you could play in this world forever and still stay true to Boulle’s and Serling’s and Dehn’s land.”

What’s more, Empire would have been the first spinoff since Marvel’s “Quest for the Planet of the Apes” to feature Mandemus, Caesar’s “conscience” in “Battle.” In a posting at the POTA Yahoo Group, Templeton said he saw the elder orangutan as having been a performer in Armando’s circus who acquired the power of speech from being in Caesar’s proximity (according to Revolution, the apes learned to speak so quickly because Caesar mentally willed them to do so).

Untitled Stories

While conceiving Revolution, Templeton decided to plant seeds for a future storyline based on a startling idea presented in the original film but never explained—that Earth had no moon in 3978. Thus, in the miniseries, Caesar experienced visions of his grandchildren involved in a global war with humans, destroying the moon in “an orgy of violence and madness.” Caesar wrote about this and other visions in a series of journals in Revolution, presented as backup features to the main story, but no further details were provided.

The moon-destructing conflict, Templeton says, would have occurred about a century or so after “Conquest of the Planet of the Apes.” Though he never worked out the specifics for such a war, his notes included the detonation of an Alpha-Omega bomb on a lunar colony. “I wanted to plant the idea in Caesar’s journal,” he says, “simply as a nod to what was one of my original thoughts about storylines.” According to Templeton, this story would have been a separate tale, not part of Empire on the Planet of the Apes, which would have occurred about 100 years before that event.

“The first, first, first thing I wrote down for the briefest notes about storylines was the destruction of the moon,” Templeton recalls. “It’s the biggest aspect of history that’s never touched upon in any of the subsequent movies, and probably a forgotten, throwaway line to future writers. But it’s stuck in my head for decades that something destroyed the moon, and we’re never told what.” A similar explanation for the Moon’s destruction, also involving the Alpha-Omega bomb, was recently rolled out in BOOM!’s “Planet of the Apes: Cataclysm” miniseries, by Gabriel Hardman and Corinna Bechko.

Moreover, Templeton says he considered writing a story about a “very small colony of apes, living in Australia, who survive the Earth’s destruction at the end of ‘Beneath,'” which he describes as “sort of an Omega Man with apes (to keep it all in the Heston zone).” This story, Templeton notes, would have suggested that ape civilization did not actually end with the bomb’s detonation in “Beneath,” but rather changed as a result.

NEXT: Boom! Studios

Rich Handley is the co-founder of Hasslein Books (hassleinbooks.com) and the author or co-author of six books: “Timeline of the Planet of the Apes,” “Lexicon of the Planet of the Apes,” “The Back to the Future Lexicon,” “The Back to the Future Chronology” (with Greg Mitchell) and two upcoming official Continuum episode guides (with Ed Gross). He has written numerous articles and short stories for the licensed Star Wars universe, helped edit Realm Press’ Battlestar Galactica comics and currently writes for starwars.com and Bleeding Cool Magazine. A former reporter for Star Trek Communicator, Rich helped GIT Corp. compile its Star Trek comic book DVD-ROM sets, wrote the introductions to IDW’s Star Trek newspaper strip reprint books and contributed to Sequart’s “New Life and New Civilizations: Exploring Star Trek Comics anthology.” In addition, Rich helped revise Ed Gross’s “Planet of the Apes Revisited” and has contributed to the POTA fanzine Simian Scrolls, in which an earlier version of this article appeared.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks