THE JOY OF KAIJU: In the final segment of our three-part series, David Hyde takes you back to the beginning…

—

With Godzilla vs. Kong out this week, comics PR maven and writer David Hyde of Superfan Promotions provides you with a three-part look at THE JOY OF KAIJU — various aspects of the ever-entertaining grandiosity of Godzilla and his fellow monsters, featuring a litany of A-List comics creators like Mike Mignola, Scott Snyder, Geof Darrow, Eric Powell and many, many more. For Part 1 — about how the King of the Monsters inspires immense creativity — click here. For Part 2 — about discovering Godzilla at any age, click here. — Dan

—

By DAVID HYDE

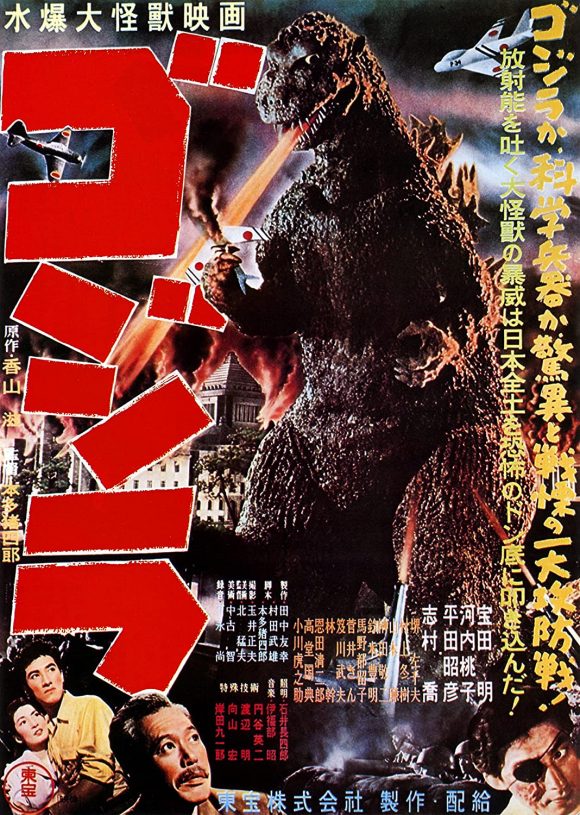

Ishirō Honda directed the very first Godzilla movie, which was released in Japan on Nov. 3, 1954. Suffice it to say: If you’ve never watched a Godzilla movie, this is where you should start. It’s a thrilling, moving look at postwar Japan, albeit one about a monster who emerges from the depths of Tokyo Bay and demolishes buildings with aplomb.

I should note that there are, technically, two versions of the movie: Honda’s harrowing Godzilla and Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, a film that was dubbed and re-edited for American audiences and released in the US in 1956, with new footage shot with American actors, including Raymond Burr (of Perry Mason and Rear Window fame). There is really no stand-in for Honda’s original.

“I grew up enjoying dubbed Godzilla movies as fun, if disposable, Saturday afternoon television fare. It wasn’t until I saw the original Japanese cut of Godzilla (1954) in a theater that it hit me how deeply felt and powerful the oft-mentioned monster-as atomic-bomb metaphor really is. The knock on kaiju films is always that the humans are superfluous, filling screen time until the ultimate monster fight. But director Ishirō Honda brilliantly used one of the great screen actors, Takashi Shimura, as the scientist, to reflect the bigger ideas of human culpability in their own destruction. Honda was not some purveyor of schlock, he was a filmmaker in the league of his friend and contemporary Akira Kurosawa. And the Godzilla series is the work of passionate and dedicated craftspeople who had something to say and said it well.”—Gabriel Hardman (Invisible Republic, Kinski)

Gabriel Hardman

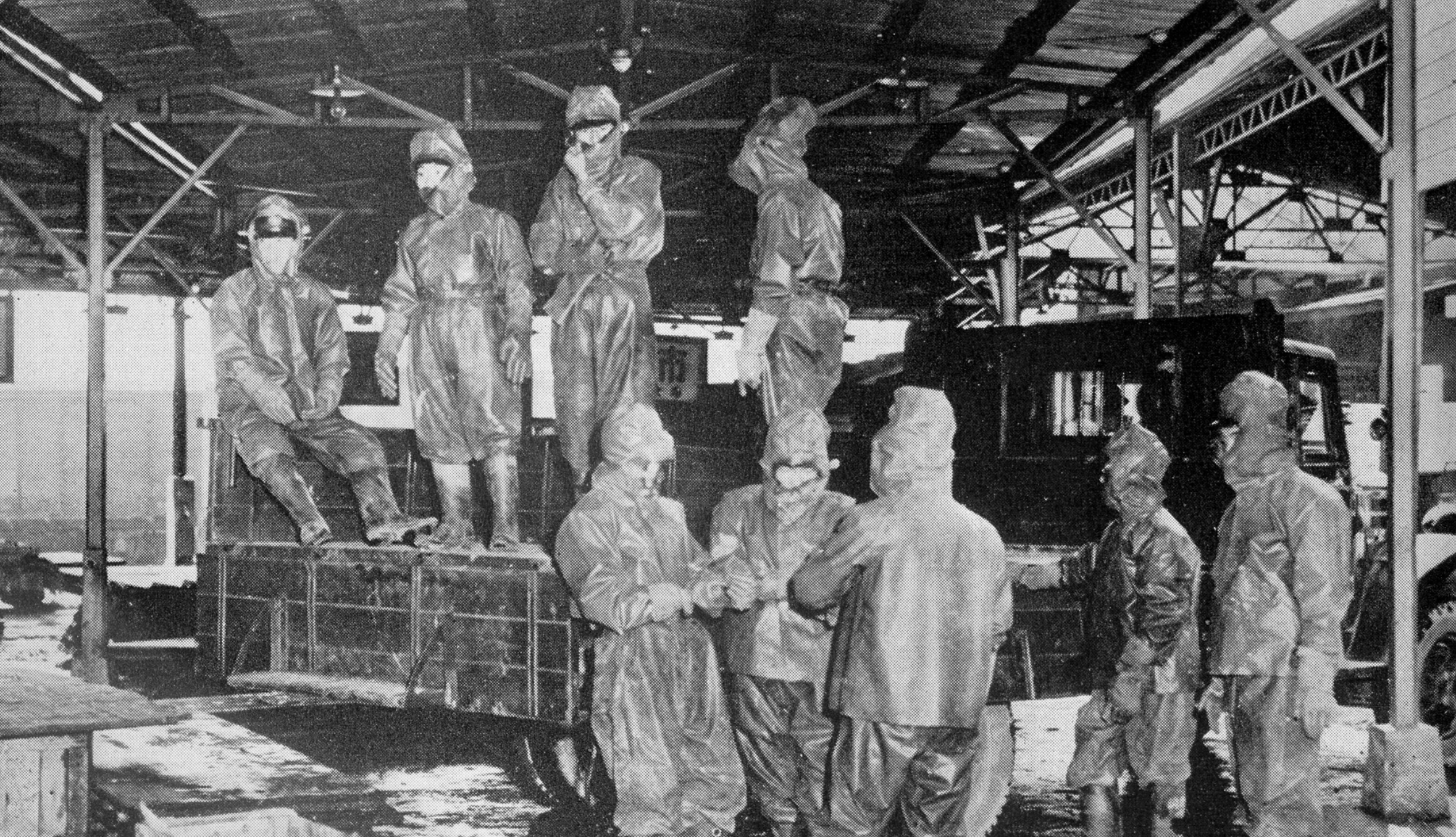

Godzilla was famously inspired, in part, by the Daigo Fukuryū Maru boat incident. On March 1, 1954, the 23-man crew of the Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) fishing boat was contaminated by radioactive dust from the United States’ Castle Bravo thermonuclear weapon test. The incident raised both awareness and anxiety about living in the atomic age.

The fear of nuclear Armageddon underscores nearly every scene in Godzilla. The film opens with a boat’s crew relaxing, as they play music. Their tranquil sea voyage is short lived. There’s a flash of light. Disaster! As the freighter sinks into the sea, a distress signal is sent out.

From the real-life incident

The parallels to the Daigo Fukuryū Maru incident would have been top of mind to a Japanese movie-going audience at the time. Honda had directed war films and documentaries for Toho’s Educational Films Division and he brings some of that sensibility here, balancing Eiji Tsuburaya’s innovative practical effects with a filmmaking aesthetic that feels — if not realistic — then, at the very least grounded by, and informed by the reality of war.

In Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski’s amazing biography Ishirō Honda: A Life in Film, From Godzilla to Kurosawa, the authors devote several chapters to detailing Honda’s time as a reluctant soldier and a prisoner of war. During the war, somewhere near Hankou, an enemy shell landed in front of him. He assumed his life was over. But the bomb never detonated. It misfired. He was saved.

Honda later went back to the scene and retrieved the 20-pound shell. He kept that shell in his study until he died Feb. 28, 1993, at the age of 81.

Hardman

“Godzilla employs my favorite storytelling trick. It uses pulp genre as a metaphor. It’s both entertaining and… if you dig a little deeper… a haunting reflection of history. It’s a brilliant bitter pill of a message put in an amazing candy coating. The best kind of art.”—Matt Kindt (Mind MGMT, BRZRKR)

In Honda’s film, Godzilla is awakened by underwater hydrogen bomb testing. The monster emerges from the Pacific and wreaks havoc on the streets of Tokyo. The city burns. Families run for their lives. Babies scream. In one particularly memorable and moving scene, a mother strives to save her children from Godzilla. Knowing full well that they’re going to die, she tells them that they will be reunited with their father, who, it is inferred, had died in the war.

The chaos and carnage in Godzilla are a far cry from the often cartoonish violence that will follow in later films, where giant kaiju will throw each other through urban areas, destroying buildings left and right, with only a modicum of consequence.

The film’s most recognizable actor is the iconic and seemingly ever present Takashi Shimura, who appeared in more than 200 films and who is cast here as Professor Kyohei Yamane. Earlier that year, in the spring of 1954, Shimura had appeared in Akira Kurosawa’s seminal Seven Samurai, as Kambei, the leader of the samurai.

Together Shimura and Kurosawa would make 21 films, including Drunken Angel (1948), Rashomon (1950) and Ikiru (1952). Shimura’s performance in Godzilla is stoic yet warm, providing a dose of gravitas and credibility to the film.

Shimura was 49 years old when the film was released. According to Ryfle and Godziszewski’s biography, Shimura took it upon himself to mentor some of the younger actors and actresses on the set, many of whom had little moviemaking experience.

“I imagine people being crushed like bugs by a huge monster who is unaware of their existence must have been the perfect Freudian dream image for the way Japanese people felt after WWII. A great film, like all great art, is a dream we share together.”—Aron Wiesenfeld (Deathblow/Wolverine, Travelers)

The monster in Godzilla is famously both awesome and sympathetic. Much of that is due to the score by the great composer Akira Ifukube.

Godzilla has one of the greatest soundtracks of all time. Ifukube was a classically trained composer and his Godzilla scores bring a melancholy and elegiac feel to the proceedings—that is when he’s not delivering the kind of searing, straight up action and adventure scores that would influence John Williams and a generation of Hollywood composers and be sampled by the likes of Pharoahe Monch and Big Sean.

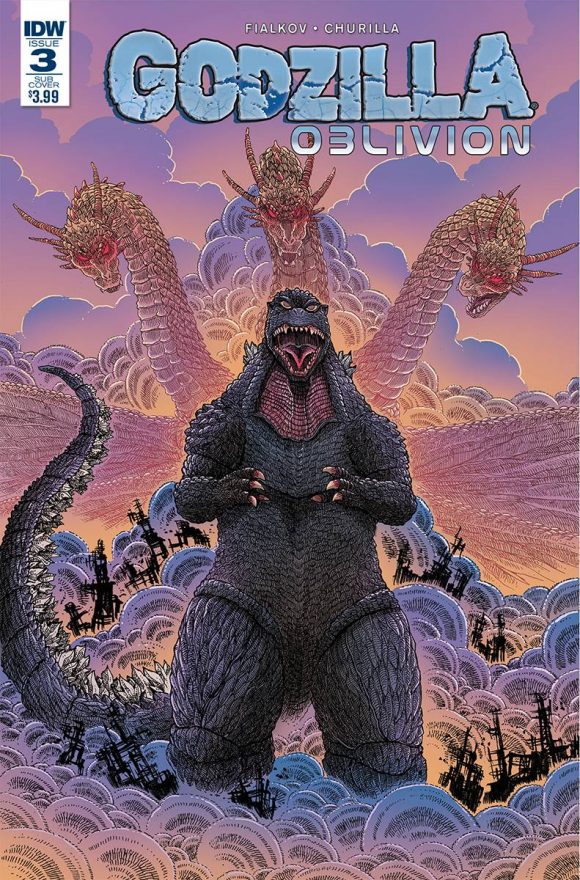

“Godzilla is the rarest of things. It’s for adults and for kids, silly and serious, suspenseful but playful. It can bend to psychedelia just as well as it can to satire. The Big G has spoken for the Trees, the People of Japan, and everything in between. Best of all, there’s a Godzilla for everyone, no matter their taste and proclivities. The character bends because of the strength of the legs underneath it. The movies have always been like looking in a funhouse mirror– except you’re almost always guaranteed to like what you see.”—Joshua Hale Fialkov (The Life After, The Bunker)

James Stokoe

Godzilla is bookended by meditative shots of the ocean’s surface, a motif Honda repeats later in 1975’s Terror of Mechagodzilla, his seventh Godzilla movie and the final film he directed. It’s a nice metaphor for the film’s environmental message and a heart-on-the-sleeve moment by the director.

Honda did not love what happened to Godzilla in subsequent films, as Toho Studios began to franchise the character. He was particularly nonplussed when, in 1965’s Invasion of Astro Monster, Godzilla struck the “shê” gag pose, which had been created and made widely popular by Fujio Akatsuka’s series Osomatsu-kun.

“Ishirō Honda, director of the first Godzilla film and seven others, said it all: ‘Monsters are tragic beings; they are born too tall, too strong, too heavy. They are not evil by choice. That is their tragedy.’”—Tom Peyer (The Wrong Earth, High Heaven)

Honda was also a lifelong friend and collaborator of Kurosawa’s, dating back to the days when Honda worked on Kurosawa’s Stray Dog, with Takashi Shimura and Toshiro Mifune. He worked with Kurosawa frequently during the 1980s and 1990s, including Kagemusha, which turned out to be the last film that Shimura acted in.

Honda was said to have turned down the title of Assistant Director on Kagemusha, in deference to Kurosawa. The two filmmakers made decidedly different styles of films, but their bodies of work nonetheless share a certain underlying empathy and a fundamental belief in the human spirit.

There are so many reasons to watch (or re-watch) Ishirō Honda’s Godzilla. The monster with his distinctive, earth-rattling roar! The groundbreaking and charming practical effects! The film’s iconic, moving score!

Godzilla is relevant today, first and foremost, because it remains a compulsively watchable movie. Honda smuggles so much of himself and his experience into the film’s genre trappings. It’s his documentary of a sci-fi dream, a nuclear nightmare that teases the possibility of a better tomorrow.

—

Many of the Shōwa Era Godzilla films are currently streaming on HBO Max. A number of Akira Ifukube’s Godzilla soundtracks are available on Spotify.

—

MORE

— THE JOY OF KAIJU, Part 1: A Kaleidoscope of Mutant Inspiration. Click here.

— THE JOY OF KAIJU: You’re Never Too Old for GODZILLA. Click here.

April 2, 2021

Great read. Thanks. I’m going to re-watch the original tonight.

April 2, 2021

I almost did last night after Godzilla vs. Kong!

April 2, 2021

Godzilla is a pretty fascinating character overall, so I appreciate you writing down this article.

April 3, 2021

I grew up on the Perry Mason version. I was a big fan of Burr.