Yesterday, I put up a column about how frustrating it is that one of the greatest Batman stories ever – the late ‘70s Detective Comics run from writer Steve Englehart and artist Marshall Rogers – is no longer in print in its entirety. I spoke to Englehart about the genesis of the run and today, he discusses its legacy and how it became one of the blueprints of the modern Batman.

The story, once collected in paperback under the forgettable title “Strange Apparitions,” is not only a tremendous Batman tale, it was extremely influential. Its DNA can be found in today’s comics, in both the Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan films, in the classic “Batman: The Animated Series,” and in even the “Arkham” series of video games.

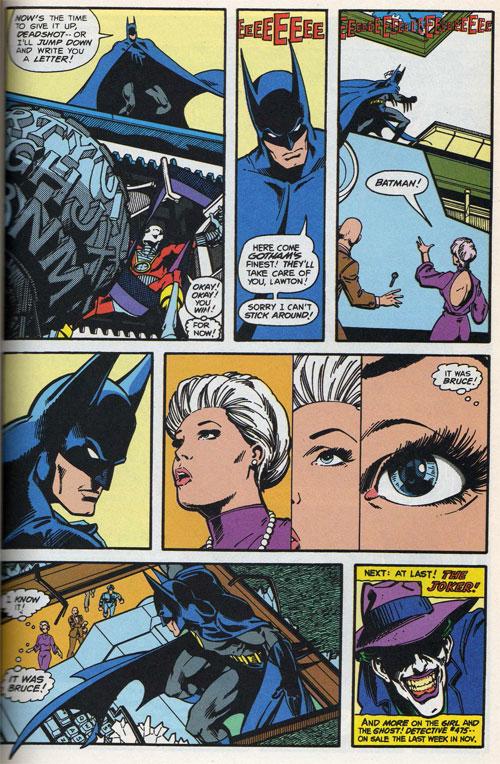

In the years after the publication of the story — an arching tale of romance and adventure featuring an array of characters new and old such as Hugo Strange, Deadshot, Rupert Thorne, Silver St. Cloud and the Joker – DC and Warner Brothers finally began seriously planning a Batman film.

The film, Englehart said, was to be based on the Detective run.

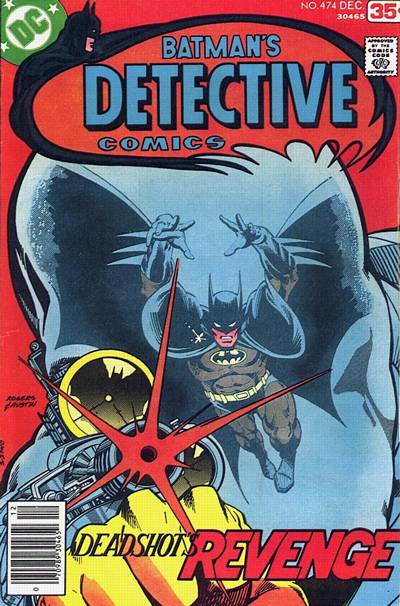

Englehart and Rogers revamped Deadshot and it was AWESOME!

“They had a series of scripts about Batman and the Joker and Boss Thorne and Silver St. Cloud,” he recalled. “But they weren’t happy with what the Hollywood pros gave them, so they eventually asked me to write treatments they could work from (under comic book standards, not guild rules).

“Finally, they made the movie, and just before filming, they changed Silver’s name, and Thorne’s name. Ever since then, it was as if Marshall and (inker) Terry (Austin) and (letterer) John (Workman) and I never existed. We never got offered anything as the films and then the animated series proliferated. The collection of our run was published under the title ‘Strange Apparitions,’ which made it a little hard to find. They never asked us to do any more Batman comics.

“So the vast majority of my time with Marshall was spent not doing Batman and feeling hard done-by — and he had actually stayed on the book after I left, and had done the newspaper strip, so he was particularly unhappy about being made a non-person,” he said.

Fast forward about 15 years.

“When ‘Batman Begins,’ was on its way, DC decided to flood the market with Bat-material, and out of the 30-year blue, we get asked to do a sequel,” he said. “And since Marshall had moved to California in the intervening years, this time we worked as a team. We lived about 40 minutes apart, so every week we’d meet at a coffee shop somewhere between and spend three to four hours swilling caffeine and talking Batman.

“I’d tell him where the story was headed and he’d critique it. He’d show me his art for the week and I’d critique it. There were two parts to that: one, we were playing directly off each other for the first time, and two, we were doing Batman, which we both loved to do. There was absolutely no sense that it was 30 years since our first outing; we knew our characters like the backs of our hands. It made us wonder what “thirty years” actually means, since it was an undeniable fact and yet didn’t have any effect at all. Seriously, if we were musicians, tapes of those meetings would be out on bootlegs.”

The six-issue miniseries they produced was published in 2005 as “Dark Detective” and was later collected in its own paperback. It was successful enough and Englehart and Rogers were working on a third installment when Rogers died suddenly in 2007.

The original story ran in Detective Comics #469-#479, with the first two issues drawn by Walt Simonson. The last three issues included a reprint of a Denny O’Neil-Neal Adams story and a two-issue coda drawn by Rogers but written by Len Wein.

Englehart recalled that he had wide latitude to use the characters he wanted.

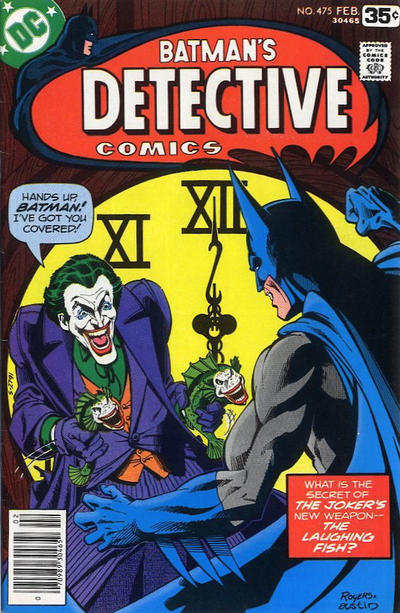

“If I was going to get a shot at one of my favorite characters, I wanted the Joker and I wanted the Penguin,” he said.

“I had seen reprints of the very early Batman, and had loved the darkness of it: lots of blacks in the art, and lots of pulp in the stories. As the guy charged with reviving him, I wanted to get that darkness back in there, so I had DC make Xeroxes of the first year of Detective from their library – there were no Archive Editions yet – and among those stories was Hugo Strange. He was the best of the pulp villains.

“But whoever I used, I had to have a contemporary story to jumpstart the book,” he explained. “So I hit upon the idea of giving Bruce Wayne a sex life. Comics in those days were done under the Comics Code, so a hero with a sex life had not only never been done before, it had never even been considered. That was the clear break between the old and the new in comic history, when I put Silver St. Cloud in bed, and had her recognize Bruce Wayne’s chin because she’d seen it up close. We still were under the Code, but I was as clear as I was allowed. The thing was, Bruce Wayne wouldn’t sleep with a bimbo, so Silver had to be his equal in many ways — a strong businesswoman, intelligent and decisive. That, too, was something new.

“So you had pulp and an insane Joker on the one hand, and Silver on the other. It illuminated the entirety of the Batman’s world, and the man inside the suit in the middle of it,” he said.

The template of the story – big, overall plot broken up into smaller, contained conflicts – has been used many times since in Batman’s world, most notably in

“The Long Halloween” and “Hush.”

“Well, Marshall and I used to joke that for a series that DC disdained, we didn’t know anybody who didn’t have copies,” Englehart said. “It was called the ‘definitive Batman’ right from the start.

“It was only later, primarily through the films, that I realized that, in making the Batman an adult, I’d solved comics’ age-old problem of selling the characters to adults. I don’t have a problem with other comics being inspired by that; that’s how comics works, and I’m honored when that happens. Good on all those guys. But if you take my formula, make a bazillion dollars off of it in film and animation, and simultaneously pretend I, and Marshall, and Terry never existed, then I do have a problem. So the thoughts on my legacy are conflicted.”

—

Truth be told, when youngster Dan discovered the story, it was Marshall Rogers’ art that was the draw. I was still learning to understand how comics worked, so it wasn’t until a bit later that I recognized the strength of the script.

But, oh, that art.

I have wistful feelings about Marshall Rogers’ career. It seems like he should have been the kind of artist mentioned in the same breath as Walt Simonson, the man he replaced in the run.

Simonson went on to a legendary career. Rogers, in my mind, never maintained the promise of those Detective issues. And he died young, at 57.

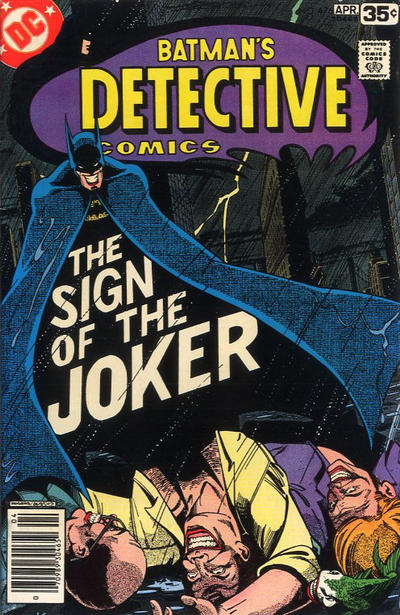

He had a wonderfully evocative style and I could go on about his storytelling techniques, the acting, the use of focus and shadows. I LOVED the way he drew Batman’s cape, with its sharp angles and points.

Yet it was his Gotham that was so extraordinary. Few if any artists have ever given me the sense of place that Rogers did.

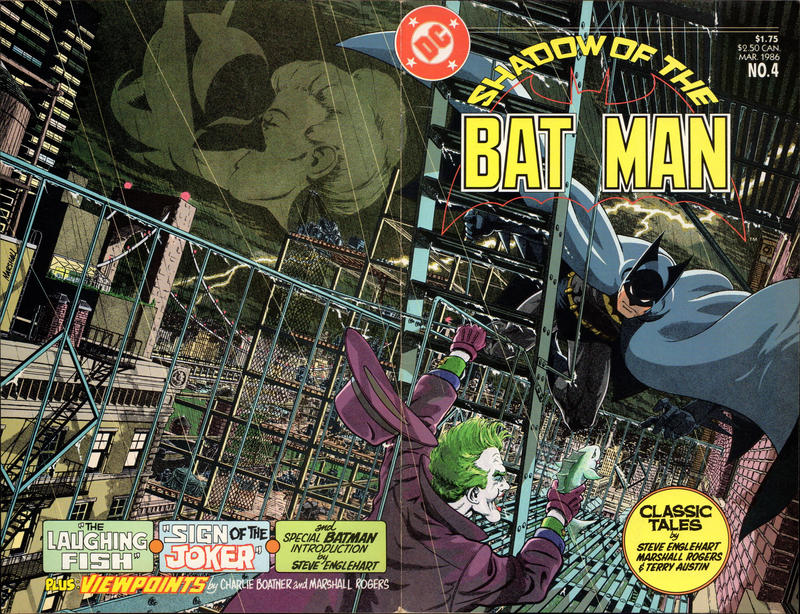

The story was reprinted in 1986 as a miniseries, Shadow of the Batman. Look at this wraparound cover from #5. Look at that detail! LOOK AT IT!

“Marshall had studied architecture on his way to being a comics artist, so you could really feel his Gotham City as a real place,” Englehart said. “Other artists could draw as realistic a city as they wanted, but Marshall really understood how cities fit together, piece by piece, so his Gotham was another character in the stories. It had real weight to it. And then he put the people high up on its rooftops.

“But you can’t laud him without adding Terry, whose line work was dark (which I wanted) and solid (which Marshall wanted). He bridged the gap between the pulp and the realism perfectly, so the finished product was as good as it could possibly be.

“As for Walt,” he added. “I can only assume that (editor) Julie Schwartz saw the talent in Marshall and Terry that others at DC did not, and figured Walt had plenty of other things to do. In those days, the editor made all the decisions along those lines. I was never consulted, and wouldn’t have expected to be; the days of asking for specific collaborators were still in the future.

“I just wrote my scripts and handed them in, so I never asked Julie, and now of course you can’t,” he said, referring to Schwartz’s death in 2004. “Naturally, I’d have been happy to work with Walt all the way through — who wouldn’t? — but Julie was the top editor at DC for a reason and not shy about running his shop his way.”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks