PAUL KUPPERBERG salutes a hero who haunts us still…

From the Season 4 episode, “The Big Freeze”

By PAUL KUPPERBERG

Faster than a speeding bullet! More powerful than a locomotive! Able to leap tall buildings at a single bound!

“Look! Up in the sky!” “It’s a bird!” “It’s a plane!”

“It’s Superman!”

Yes, it’s Superman, strange visitor from another planet who came to Earth with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men!

Superman…who can change the course of mighty rivers, bend steel in his bare hands, and who, disguised as Clark Kent, mild-mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper, fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice, and the American way!”

—Opening narration of The Adventures of Superman TV program (1952-1958)

According to legend, the house at 1579 Benedict Canyon Drive in Los Angeles where actor George Reeves (born January 5, 1914) died of a gunshot wound to the head early in the morning of June 16, 1959, is haunted. The coroner had ruled the 45-year-old actor’s death a suicide, brought about by despondency over a failing career and too much alcohol. Reeves (born George Keefer Brewer, later Bessolo, after his mother’s remarriage) had some early success as a film actor beginning in 1939 when he was cast as one of the Tarleton Twins in the epic Gone With the Wind.

Reeves would eventually find himself starring with Claudette Colbert (the Sandra Bullock of her day) in Paramount’s So Proudly We Hail (1942), a war film made shortly before he was drafted into the real U.S. Army Air Force in 1943. The actor remained stateside, with duties that included appearing in both the Broadway and Hollywood film versions of Winged Victory, a USAAF production, and making training films.

The Hollywood he returned to after his discharge in 1945 was an industry town in transition, with fewer production companies making fewer films. Instead of appearing opposite such stars as Jimmy Cagney, Ronald Reagan, and Merle Oberon as he once had, George was now starring in Saturday morning costumed serials, Westerns, TV anthology programs, and on radio.

Fred Crane, Vivien Leigh and George Reeves in Gone With the Wind

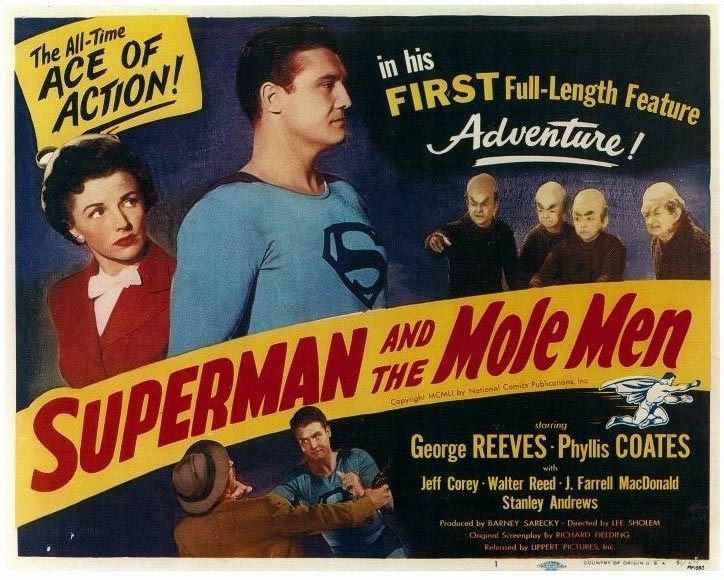

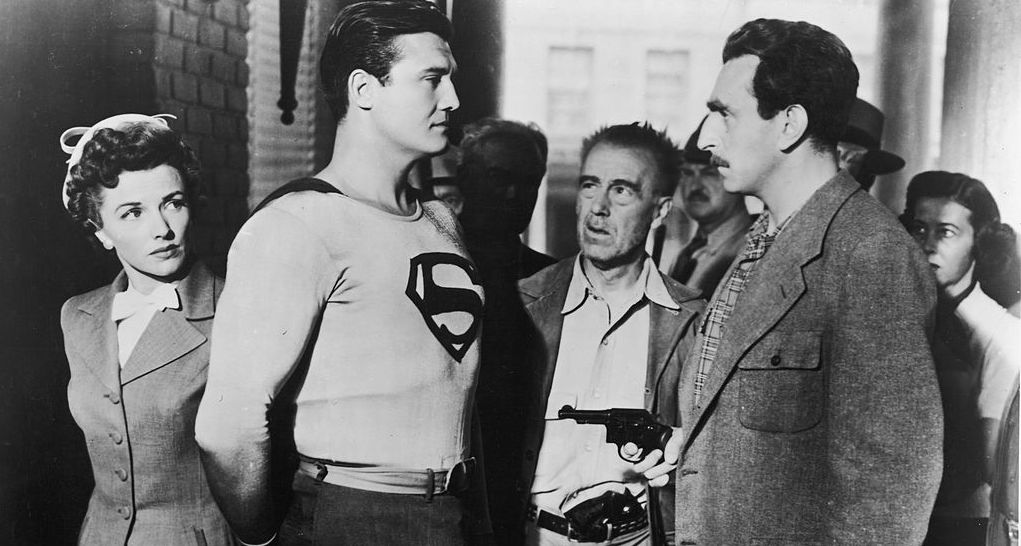

He also signed to play the lead in a syndicated weekly kid half-hour adventure program, The Adventures of Superman. Reeves took the role of Clark Kent/Superman—based on the DC comic book character as well as its predecessor radio program, which aired from 1940 to 1951—in the low-budget show for the paycheck, confident the pilot would never be sold. But in 1952, ABC picked up the show (shot as the theatrically released Superman and the Mole Men in 1951 and carved up into two half-hour episodes) and he would spend the next six years, for 104 episodes (plus a guest shot as himself in the costume on I Love Lucy and countless personal appearances at everything from Wild West shows to supermarket openings) as Superman.

The last few years of George Reeves’ life, some of which was dramatized (in fictionalized form) in the 2006 film, Hollywoodland starring Ben Affleck as the actor, seemed somewhat sad and desperate. In 1953, already identified with the costume, he was cast in a minor role in From Here to Eternity, a big budget film highly anticipated for, among other things, a performance by crooner and actor Frank Sinatra who was also hoping for a comeback after his own career had hit the skids. Sinatra won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. (Apocryphally, Reeves barely made it into the film when most of his part was excised after preview audiences began to excitedly whisper “Look, it’s Superman!” when he appeared on screen. But he had been typecast out of serious acting.)

A lot of people think weariness with his iconic but unfulfilling image as a kid show superhero and lack of work since the TV series had wrapped up production led to Reeves putting a gun to his head and pulling the trigger that night of June 16. Others claim Reeves was anything but despondent, that his death was a homicide, likely accidental, possibly deliberate. They claimed he had everything to live for. He was engaged to be married and was in pre-production for a new season of 29 episodes of Superman, several of which Reeves was scheduled to direct.

Whatever his state of mind, whoever pulled the trigger, the actor George Reeves died that night in the upstairs bedroom. The newspapers trumpeted headlines like “TV Superman Kills Himself With Gun,” the irony of an actor playing a character billed as being “faster than a speeding bullet” dying by a gunshot wound lost on no one. But even in death “Superman” grabbed the headlines, relegating George to the small print beneath it, like Clark Kent’s byline on a Daily Planet story about Superman’s heroic deeds. Reeves was still being typecast, postmortem.

Still, the headlines didn’t get it right. Superman couldn’t die, and George Reeves hasn’t been allowed to.

The whispers of conspiracy and cover-up began circulating almost immediately. Despite being only a player in the television ghetto, Reeves traveled in the loftier and often literally cutthroat circles of old Hollywood studio politics. His ex-girlfriend, the one he dumped for the socialite he was engaged to marry, was herself married to a powerful studio executive with connections to organized crime and a corrupt police department. The romantic entanglements and subsequent intrigues and forensics are easy enough to look up yourself but don’t, in the long run, matter. It was an unhappy end to a seemingly unfulfilled life. If 1579 Benedict Canyon Drive is haunted, it’s no wonder his spirit can’t rest.

His ex-lover inherited the house after George’s death, but she had trouble keeping it rented. Tenants reported hearing strange noises from the late actor’s bedroom, including that of a single gunshot. The room would be found in unexplainable disarray, with pillows, sheets, and clothing strewn about or furniture moved. George himself would appear in the house or on the front lawn, sometimes in costume as Superman.

If his iconic role hadn’t been enough, the mystery surrounding his death and afterlife served to cement his place in American pop culture. Too bad he had to land in the part of it that worshipped the Hollywood necrocracy, that pantheon of the emotionally and physically wounded and the tragically dead or terribly mutilated. The ghost of George Reeves was condemned to drift alongside those of Jayne Mansfield, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Bruce Lee, Elvis, and the rest of the tabloid spirits.

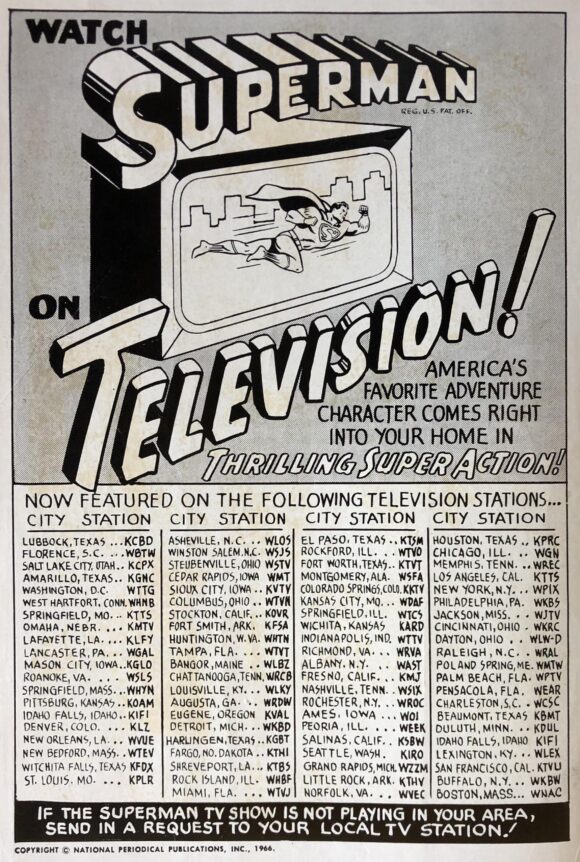

The Adventures of Superman lived on in syndication, five days a week, its 104 episodes cycling endlessly in front of kids across America. Six or seven years after the last first-run episode aired in 1958, I was one of those kids who raced home from school so I could be in front of the TV for the opening glissando of the theme song, repeating those time-tested words along with the announcer. “Faster than a speeding bullet…!”

I knew that most of what I saw on television was a lie. No one I knew lived lives that came even close to those I saw on Father Knows Best, Leave it to Beaver, The Donna Reed Show, and the rest. Real kids weren’t that stupid, real moms that clueless, or real dads that goofy. And real families, if mine and those of my friends were any indication, never that happy.

But Superman wasn’t about squabbling siblings or kids trying to hide a broken vase from their folks. He was up to the serious business of fighting a never-ending battle for truth, justice, and the American way. Of course, I knew Superman himself didn’t exist. He was just a character on a television show and in the comic books, but what he stood for was real enough. It was a message that resonated in the 1950s and early 1960s, when patriotism was in full bloom, when a kids’ pride in being an American was bolstered by the real-world superheroics of the NASA astronauts, even then riding rockets into outer space, where Superman himself had come from.

The message struck home with me. I was an unhappy kid in a dysfunctional home, but Superman gave me something to believe in, something to cling to. Truth, justice, and the American way.

I didn’t know at the time that the America Superman stood for was a white America. Not that Superman himself was prejudiced. In fact, he urged his young readers to remember “People are People,” the title of a one-page public service ad from the 1953 comic books. Superman admonishes a man who assumes that it was the white kid who had performed a heroic act. “Wait a minute!” Superman exclaims, “How do you know it wasn’t the other lad?” The man stammers helplessly, “Why–er…why–er…,” until Superman sets him straight: “Because of his color? As a matter of fact, he was the one! You just jumped to the conclusion because of a common prejudice!” The Man of Steel reminds us of an elementary truth, “That people are people, and should be judged as such, regardless of color or beliefs!”

The ad was for “Brotherhood Week, February 15-22… But the ideas behind it should be observed all year.”

Except, apparently, in the Metropolis of the television show and the comic books. Superman said in the ad that Black lives mattered, but if you looked at the world around him, Black lives were virtually non-existent, and those who did occasionally appear were usually played as stereotypes. I grew up in predominantly white neighborhoods in Brooklyn, but the schools I went to and the kids I played and mingled with were mixed. Still, I was a lower middle-class white kid, and my experiences, most of my friends, and my consciousness were shaped by that.

I was one of the lucky unhappy kids. Thanks to Superman, I found escape with a community of likeminded friends. The show intensified my interest in comic books, leading me to make friends with other readers and discovering, through them, the wider world of comic book fandom. There were few Black comic book fans in organized fandom, at least that we encountered. The medium didn’t necessarily speak to their experiences as kids of color. Comic books didn’t have any role models for them, no characters who looked like them that they could aspire to. And their experience of justice and the American way was vastly different from mine.

I was 9 or 10 years old, too young to know about or understand the equal rights movement exploding around me while I was watching The Adventures of Superman. I didn’t wake up to reality until I was 12 years old, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed in Memphis, Tennessee. There was no Superman to stop the bullet that took his life, no champion for truth, justice, and the American way to quell the violence or mend the destruction it left behind. And there was no denying that things changed that day.

I couldn’t understand why I was suddenly a bad guy just because I was white. I was powerless to change things. I was an overweight, victimized schlemiel. I couldn’t stand up for myself, much less anybody else. I didn’t wish anybody harm and all I wanted was for the rest of the world to respond to me in kind.

An acquaintance who worked in a store across from a low income housing project in Detroit that sold comic books in the early-1970s once told me that customers of all colors routinely picked up a fairly wide range of titles, but that a majority of his black customers also picked up The Incredible Hulk and Richie Rich, characters who are green or about as lily white as they come, but who, he surmised, represented power and wealth, which is, I suppose, just another shade of green, no matter your race. Comic books were struggling with offering Black readers characters they could relate and aspire to. Of those introduced in the 1960s and 1970s, the white creators and publishers of some even felt it necessary to label them: Black Lightning. Black Panther. Black Goliath.

It came as a surprise to me one evening in July when I heard the opening narration from Adventures of Superman coming out of my TV, then tuned to MSNBC, and in a voice other than that of announcer Jackson Beck, who had recorded the 1950s original.

The speaker was Dallas police Chief David Brown, speaking in the aftermath of the July 7, 2016, ambush shootings of 14 of his police officers during a peaceful Black Lives Matter rally, resulting in the death of five of them. Chief Brown was credited with heading up one of the most progressive police departments in the country, much less the South, a proponent of community policing and a champion of tolerance and human rights for victims and victimizers alike.

Chief Brown opened his comments with the words that can still give me goose bumps: “‘Faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound. Look, it’s a train, it’s a plane…it’s Superman.’”

Chief Brown, whose life includes a son lost to mental illness and violence and a younger brother killed in the line of duty as a cop said, “As a young child I ran home from school to hear that. So that I could see the reruns of the television series, Superman. I love superheroes because they are what I aspired to be when I grew up. They’re like cops. They’re like police officers. Superheroes. And cops are mission focused. Give us a job to do, we’ll focus on accomplishing the mission.”

Chief Brown, born in July of 1961, who watched the same ghost of George Reeves flicker across his TV a few years after I had, said, “We want to be Superman—we are the last to ask for help.”

David O’Neal Brown, the respected Black police chief of a major Southern city, ended his emotional remarks by reprising those famous words, changing out a fictional hero for the names of a quintet of real world fallen:

“Faster than a speeding bullet. More powerful than a locomotive. Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound. Look it’s a train, it’s a plane, no, it’s Patricio Zamarripa. Look, it’s Brent Thompson. Look, it’s Michael Krol. Look, it’s Lorne Ahrens. Look, it’s Michael Smith.”

When Chief Brown and I were growing up, there was only one Superman. Kirk Alyn had played the role in a pair of movie serials (1948’s Superman and 1950’s Atom Man vs. Superman), but those never showed up on TV and therefore didn’t exist as far as we were concerned. In the decades since, more than half a dozen actors have played the Man of Steel on TV and in movies, among which only the late Christopher Reeve stands among serious fans as a possible contender for the title of definitive Man of Steel. Reeve was great in the part, a steely blue-eyed Boy Scout who made the Spandex work, but for Chief Brown and the rest of my generation, there can be only one.

The episodes of The Adventures of Superman we watched those countless afternoons, me in Brooklyn, he in Dallas, more widely separated by our backgrounds than distance, inspired us both, me to flights of fancy as a writer, Chief Brown to become a cop, a real-life superhero.

But looking back on it, almost half a century later, I no longer believe we were running home to see Superman as much as we were to watch George Reeves as Superman. It’s impossible to envision another actor under that cape. Whether he hated the role or loved it, Reeves brought an idealistic, big brother warmth to Superman. Christopher Reeve may have made us believe a man could fly, but George Reeves made us believe a man could be a superman who could be trusted with all those powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men. His calm, self-effacing heroic demeanor and his reassuring smile brought a decade of kids through Cold War fears, and he left behind a 104-episode legacy for frightened, abused kids like me, and for kids who didn’t seem to be afraid of anything.

It’s Superman we wanted to be, but it was George Reeves who made us want to be him. I can’t say what goes on at 1579 Benedict Canyon Drive, whether George haunts the premises rearranging furniture and scaring away tenants, but I have lived with his gently smiling specter looking over my shoulder almost my entire life and he’s brought me nothing but comfort and hope.

Superman can change the course of mighty rivers but it’s beyond even his powers to change the ways of closed minds and hateful hearts. To those open to his message and example, however, there was nothing we couldn’t do, whether it was for a bullied white kid from Brooklyn to grow up to himself one day write the adventures of Superman, or a determined black kid from Dallas to follow Superman’s lead to a decorated 30-plus year career in law enforcement.

The comic book and film personas of Superman have changed countless times over the years, evolving with social mores and levels of audience sophistication, but George Reeves’ Superman remains frozen in its time and place. He was the last Superman to both play directly to the young and naïve and to cut to the heart of “truth, justice, and the American way.”

And that’s how, more than 65 years after kids first heard those words used to introduce a low-budget, syndicated children’s TV program, the country heard them being invoked by a Black chief of police to honor five of his murdered officers, Patricio Zamarripa, Brent Thompson, Michael Krol, Lorne Ahrens, and Michael Smith. I don’t know the race or religion of any of them, only that they all wore blue.

Just like Superman.

So maybe his ghost isn’t the only thing George Reeves left behind. I can’t speak to what it was in his Superman that appealed to Chief Brown. Call it hope. Call it inspiration or aspiration. For myself, whatever it is, I hope that part of George Reeves haunts me forever.

—

“The Ghost of George Reeves” was written in 2016 for an anthology about American heroes that never appeared and was subsequently published online in slightly altered form in 2018.

—

MORE

— GEORGE REEVES’ SUPERMAN: It Took Decades But I Finally Get What Made Him Great. Click here.

— Here’s the SUPERMAN ’55 Comic That DC Needs to Publish. Click here.

—

PAUL KUPPERBERG was a Silver Age fan who grew up to become a Bronze Age comic book creator, writer of Superman, the Doom Patrol, and Green Lantern, creator of Arion Lord of Atlantis, Checkmate, and Takion, and slayer of Aquababy, Archie, and Vigilante. He is the Harvey and Eisner Award nominated writer of Archie Comics’ Life with Archie, and his YA novel Kevin was nominated for a GLAAD media award and won a Scribe Award from the IAMTW. Now, as a Post-Modern Age gray eminence, Paul spends a lot of time looking back in his columns for 13th Dimension and in books such as Direct Conversations: Talks with Fellow DC Comics Bronze Age Creators and Direct Comments: Comic Book Creators in Their own Words, available, along with a whole bunch of other books he’s written, by clicking the links below.

Website: https://www.paulkupperberg.net/

Shop: https://www.paulkupperberg.net/shop-1

January 5, 2024

George was one of the greatest. After his passing, they tried The Adventures of Superboy. It wasn’t too bad. [only] The pilot episode still floats on YouTube. I often wonder about the young actor that portrayed him and his whereabouts.

January 5, 2024

They also made an “Adventures of Superpup” pilot with dwarves wearing dog costumes and using the “Adventures of Superman” sets. It’s probably on YouTube as well, but also in the Superman anthology DVD and Blu-Ray collections (but not in the 4K collection).

January 5, 2024

This article brings this song to mind: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1h_VnuzcttM

January 5, 2024

Nice piece, Paul. Fact check: Willard “Bill” Kennedy (June 27, 1908 – January 27, 1997) was an American actor, voice artist … began his career as a staff announcer in radio; Kennedy’s voice narrates the opening of the television series Adventures of Superman. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Kennedy_(actor). (Main Wikipedia article on the TV show says the same, and I’ve read that before, maybe in Gary Grossman’s book? I remembered his last name because … well, you know.) From what I’ve read elsewhere, the recording session for that opening ran into the wee hours of the morning. For my comments on the sudden realization I had about how that handgun in the opening sequence was filmed, see my response to your previous article here: https://13thdimension.com/paul-kupperberg-my-13-favorite-things-about-the-adventures-of-superman-ranked/

January 5, 2024

Very well done, Paul. I worked as a journalist in a variety of capacities for 41 years, and this is one of the most thoughtful and insightful pieces I’ve seen. I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to read it.

January 5, 2024

Wonderful, Paul! Thank you for this! I’m glad you found inspiration in that show!

January 6, 2024

Jim Beaver, who is writing a George Reeves biography, talked to both the director and screenwriter of FROM HERE TO ETERNITY before they passed. Both have stated that none of George’s scenes were cut, and there was no additional scenes with his character in the script.

January 6, 2024

Great piece Paul. We were lucky to have Chief Brown here in Dallas to led the DPD through that terrible evening. I appreciate the link you made for you and him through Superman.

January 7, 2024

Beautiful essay. George was my first Superman, too (mid-1970s syndication), though it was only a couple of years later that Chris’s Superman came out. I find Reeve astounding for the kindness and emotional strength he portrayed, but Reeves was tougher. In a fight, I pick George.