BATMAN ’66 WEEK: An anniversary dive into the show’s impact…

—

UPDATED 1/14/25: It’s BATMAN ’66 WEEK — celebrating the anniversary of the show’s debut Jan. 12, 1966! This piece first ran during our 2019 BATMAN ’66 WEEK. For the complete 2025 index of features, click here.

—

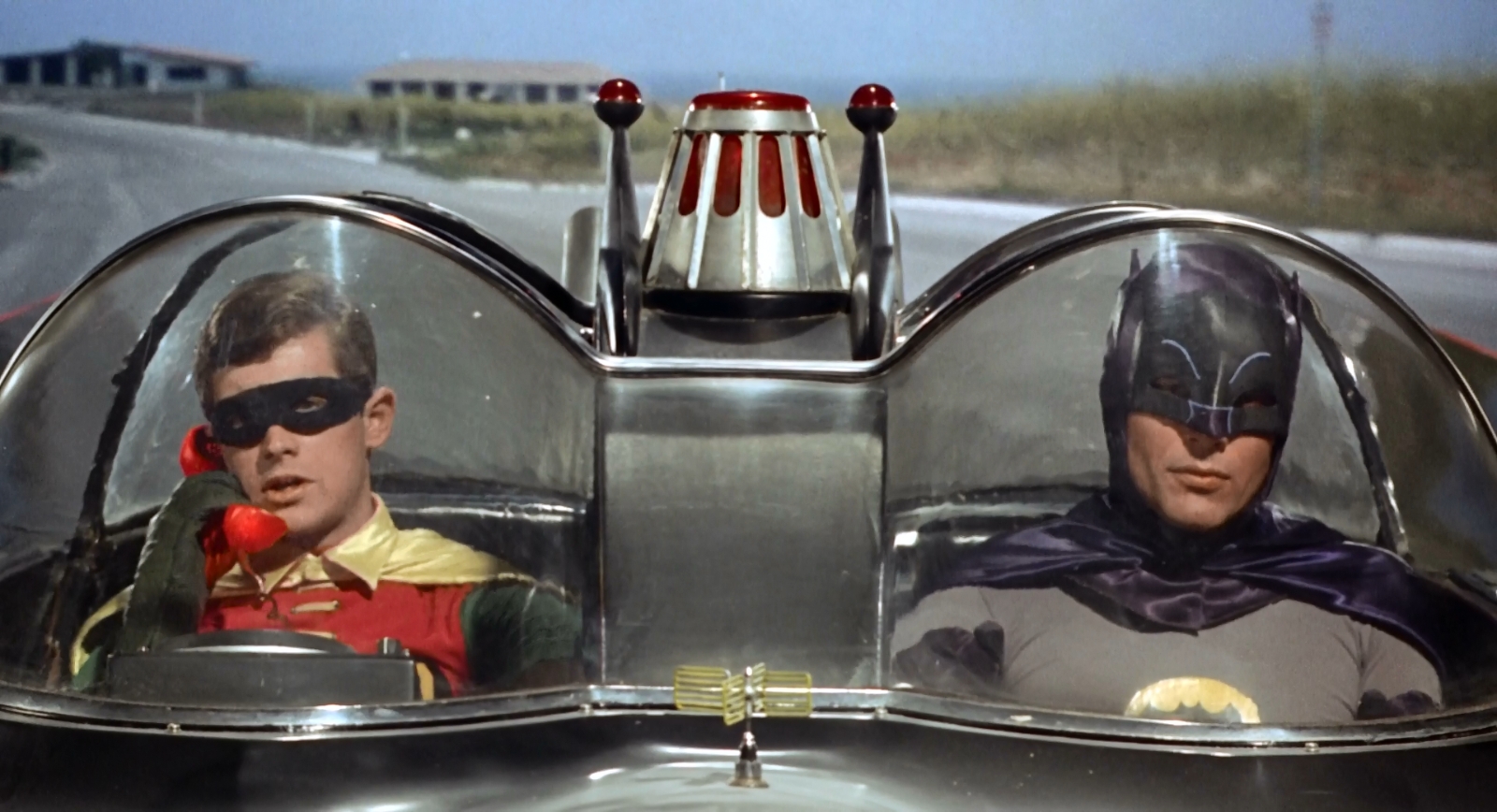

It’s an old saw among fans that the immense success of the 1966 Batman show led DC’s editors to match the program’s campy tone in the Caped Crusader’s comic books. And it’s true — though not to the degree you might think.

Mostly, it was in the trappings.

Yes, sales went up. Yes, Batman was featured more prominently on covers for books like Justice League of America. Yes, the Detective Comics logo was altered to more prominently feature Batman. Yes, Batman was made the headliner in The Brave and the Bold. Yes, Robin’s role in Teen Titans was played up. And, yes, Batman was given top billing over (GASP!) Superman in World’s Finest.

But inside the pages of Batman and Detective themselves, substantive tonal changes were more gradual and somewhat subtle. In fact, many issues that modern readers would consider campy actually predated the show. (Time’s a flat circle, folks: The show itself drew inspiration from them.)

Anyway, a quick bit of background: By the early ’60s, the Caped Crusader’s mags were deemed out of date and creatively moribund. (They were.) Enter editor Julius Schwartz and artist Carmine Infantino, who launched Batman’s “New Look” in 1964: Schwartz dispensed with the books’ technicolor aliens and absurd villains like Mr. Polka Dot and Planet Master…

… and introduced a more grounded approach to the storytelling. (They even killed off Alfred — though they later brought him back to line up with the show.) Infantino modernized Batman’s look and surroundings, and perhaps just as importantly, took over cover duties while periodically producing interior art.

But it wasn’t exactly a return to the character’s pulp roots. Major villains like the Joker and Penguin were still candy-colored thieves and plots often centered around misguided inventors or gangsters who happened upon supposedly science-based machinery that aided them in their bizarre crime sprees. Further, most of the interior art was still pencilled by Sheldon Moldoff, who adhered to Infantino’s newly installed house style but whose work remained generally wooden and rudimentary when compared to many of his contemporaries.

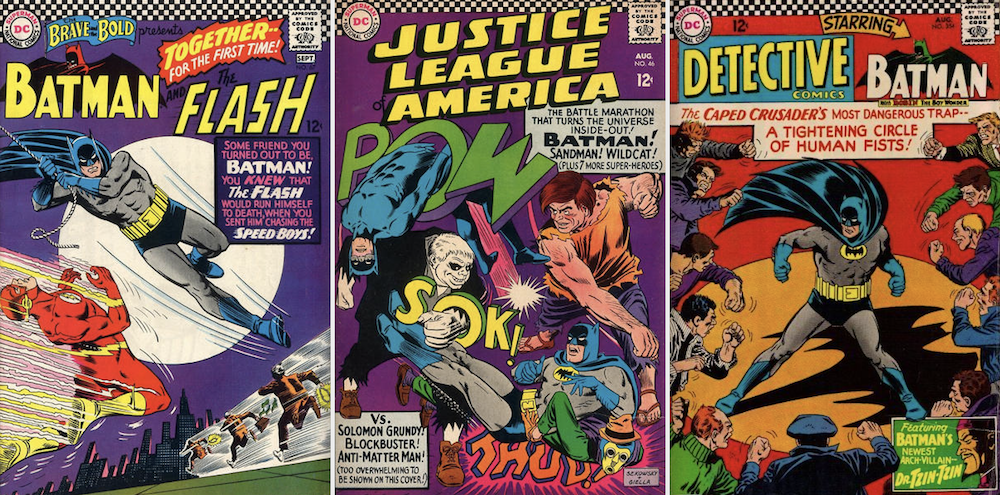

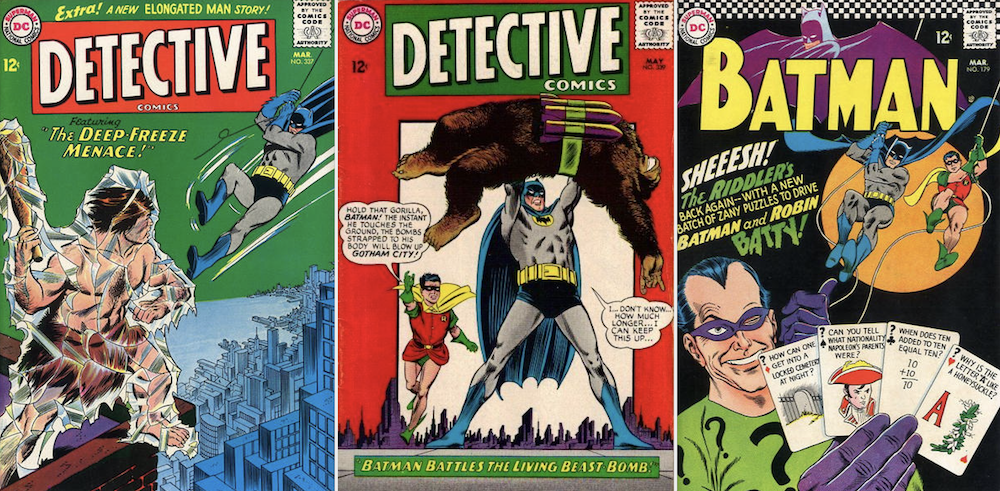

Just look at these issues released from 1964 to mid-1965, well before the show debuted Jan. 12, 1966:

Left and center: Carmine Infantino pencils and Giella. Right: Infantino pencils and Murphy Anderson inks.

Great fun, sure, but not exactly sober storytelling.

Still, after the show’s premiere — and amid the attendant Batmania — changes began making their way into Batman and Detective by the middle of 1966: Robin started spouting “Holy” this and “Holy” that and visual “sound effects” in fight scenes were made more prominent, for just two examples. (At the same time, The Brave and the Bold, edited in a different office and written by “Zany” Bob Haney, adopted a wacky tone but that was how Haney rolled anyway.)

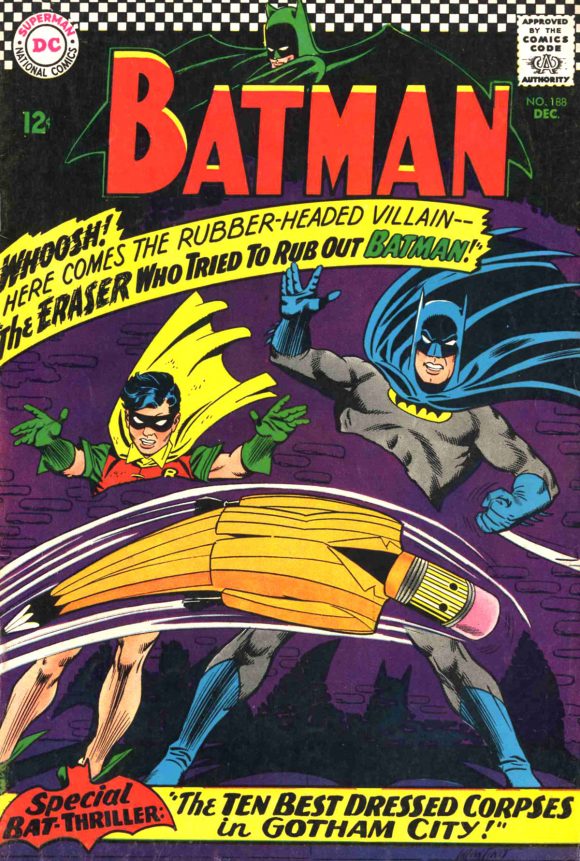

It all came to a head, however, in Batman #188 — the precise issue where the sensibility of the TV show was stamped over the Dynamic Duo’s comic-book world:

Pencils by Carmine Infantino, inks by Joe Giella

The cover itself is a camp classic, and one often cited by fans as emblematic of this very period. But the devil’s in the details, as they say, and you can’t appreciate just how much Batman producer William Dozier’s vision had infiltrated the DC offices until you look inside the issue, which is cover-dated Dec. 1966 but was on sale in October of that year, according to the Grand Comics Database.

The lead story — The Eraser Who Tried to Rub Out Batman!, written by Robert Kanigher, pencilled by Moldoff and inked by Joe Giella — reads simultaneously like a half-hearted attempt to emulate the show and a listless parody of it. It can be charitably described as “not good.”

In a nutshell, a mistake-prone friend of young Bruce Wayne named Lennie Fiasco (!) grows up to become a would-be supercriminal, the Eraser — decked out like your favorite Ticonderoga or Eberhard Faber pencil:

That would have been enough but the overcooked story — replete with silly dialogue — goes on to include a scene where Batman is besieged by adoring women, much to Robin’s chagrin…

… a Batclimb…

… and the issue’s legitimately exciting highlight, a full-page Batfight:

This last one is particularly notable: Sure, you have your oversize, over-the-top “sound effects.” But what’s really significant is that it’s a splash page — an exceptionally rare occurrence in Batman’s Silver Age comics. Clearly, the creators were mimicking the way the Batfights were the action centerpieces of the show.

There’s even a second one later in the story — again, a la the show — and Batman hums while he fights!

It was a far cry from the muted way DC announced the show to fans months earlier (Click here for much more on that.)

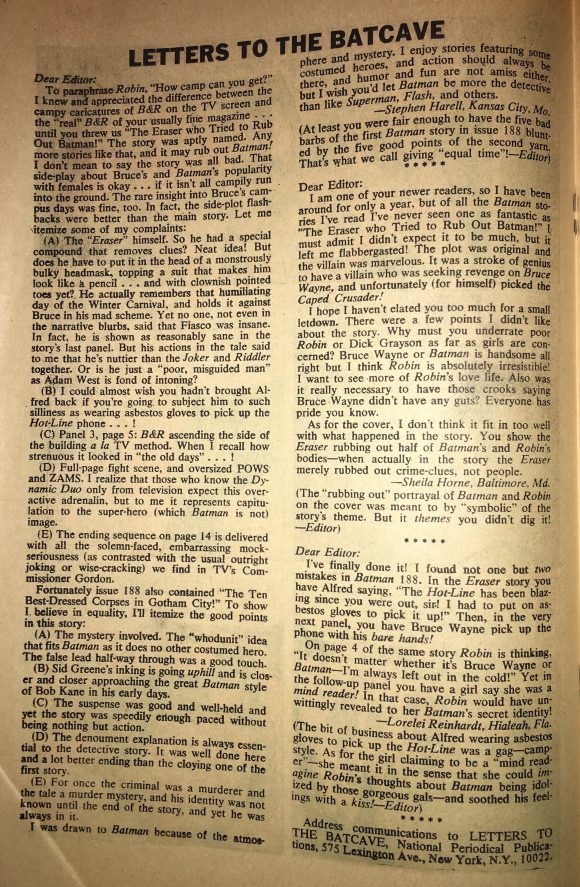

The show’s impact on the issue was noticed by fans, too. Several months later, in Batman #191, DC published a letter by reader Stephen Harell, who’d put together a list delineating the show’s effect on Batman #188:

The program’s influence would continue to be felt for some time and a major milestone was around the corner too: A month after Issue #188 was released, Batgirl — conceived in concert with the show’s producers — made her debut in Detective Comics #359 in November 1966.

But the issues that followed Batman #188 weren’t quite as arch, which is just as well.

Because if Batman #188 proves anything, it’s that writing clever camp is a lot harder than it looks.

—

MORE

— BATMAN ’66 WEEK Index of Features. Click here.

— Check Out DC’s Strange Announcement of the BATMAN ’66 TV Series. Click here.

January 12, 2019

I grew up with the Batman TV series and I loved the camp humour and capers as did my Dad who got me into Batman……..Holy TV Batman!

January 12, 2019

This post is pretty great.

January 12, 2019

The “sound effects” words in comic books or on TV, actually have a name : onomatopoeia. You can look it up.

January 13, 2019

OK

January 13, 2019

For a more in depth look at this subject I highly recommend Will Brooker’s “Batman Unmasked”. In the chapter entitled “1961-1969 Pop and Camp” the author shows that:

The Batman comics were pretty dang campy long before the show aired.

The show did have an influence on the comics, but DC had certain rules they made Dozier follow and weren’t afraid to make corrections to scripts prior to shooting.

The urban legend that the show saved the comics was in fact the truth.

Basically, there was a symbiotic relationship between Schwartz and Dozier and both influenced the other with their individual properties. I would say the comics had the largest influence when you consider how many episodes were adaptations of DC comic books. To learn more on that read “Batman – The TV Stories”.

Bottom line for me is that Dozier was attempting to bring the comic book to a live action production. On that he certainly succeeded.

January 13, 2019

“The character’s pulp roots.” Nope. Batman doesn’t have “pulp roots.” His roots are being the opposite of Superman (even down to his costume colors). He can’t fly, he swings. He can’t throw a car, he drives one.

January 13, 2019

It is well documented that one of the many inspirations for Batman’s creation were the characters found in the pulp publications such as The Shadow.

http://www.thegeekedgods.com/batman-his-surprising-link-to-classic-pulp-comics/

January 14, 2019

Agreed. It’s been established for decades. Not a controversy.

January 15, 2019

Slight correction, Dan == Batman #179 was cover-dated March, 1966, and would have come out in January, around the time of the TV show’s premiere.

January 15, 2019

You are correct! Very good point. That said, it was still too early for the show’s impact to be reflected in the comics.

August 31, 2019

I have always believed that Batman #179 was deliberately timed to be on the newsstands when the TV show premiered. Although the stories may not yet be “camp,” the cover design and Riddler appearance certainly evokes the TV show.

January 16, 2019

I like the EASER. Wish he made more appearances.

Easer did have a cameo in the LEGO BATMAN MOVIE. YAY!

January 16, 2019

Yes he did! I was hoping he was gonna be the main villain!

January 14, 2025

The letters column reveals another effect of the show on the comics: new readers, as evinced by the second, and possibly third, letter.

January 14, 2025

I hope that lady who kisses Robin isn’t *really* a mind-reader, considering his thoughts gave away Batman’s secret identity!