MORRISON MONDAYS!

By BILL MORRISON

When people come to my table at comic book conventions across the country, the question they ask the most is “How are The Simpsons writers able to predict the future?” The second most-asked question is “Are you really the artist who painted a penis in The Little Mermaid video box art?” When I answer “Yes,” the follow-up query is always “Did you do it on purpose?”

It’s a great question. According to the urban legend that went around after the release of The Little Mermaid on home video, the anonymous Disney artist who painted the box art was fired while still working on the illustration, and as a final act of revenge, he hid a phallus amid the towers in King Triton’s castle. As urban legends are wont to do, the account got more and more salacious as time went on. It was like that game, “Telephone,” and it seemed that every time someone said to a friend, “Did you hear about the penis in The Little Mermaid video box art?” something new and more outrageous would be added to the story. But staying with that initial rumor for a bit, is any part of it true? And is that level of rebelliousness something that I’m even capable of?

Me, at the Reagan Library

To answer those questions, a little history on the origins and specifics of my career may be helpful. Before I started writing and drawing comics, I worked as an illustrator in Hollywood. My first job was doing movie poster art at B.D. Fox Advertising, a sort of boutique ad agency that specialized in film and TV campaigns. It was like the Sterling Cooper agency in Mad Men, but specifically for showbiz ad campaigns, and it occupied a cool 1920s building on Sunset Boulevard that was designed to look like an Art Deco ocean liner.

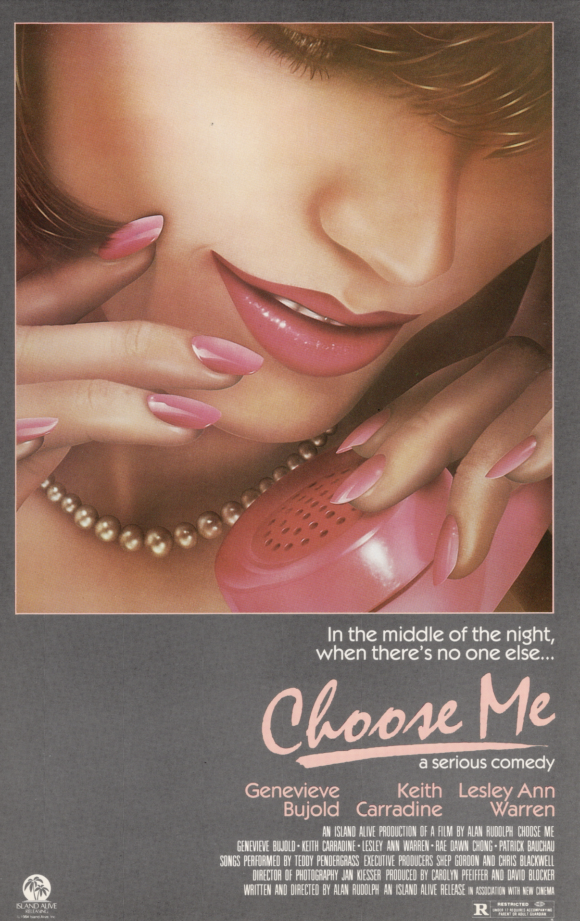

There, I illustrated posters for horror movies such as House and Blood Diner, art house and foreign films like Choose Me, and The Hit, and low-budget action films, most notably Cocaine Wars, and Roger Corman’s Wheels of Fire. But I was the in-house illustrator, so I did whatever needed to be done, art-wise. I drew a lot of rough sketches and painted a bunch of comps for ’80s classics like Return of the Living Dead, Fright Night, and Maximum Overdrive. I did a fair amount of old school pre-Photoshop retouching as well.

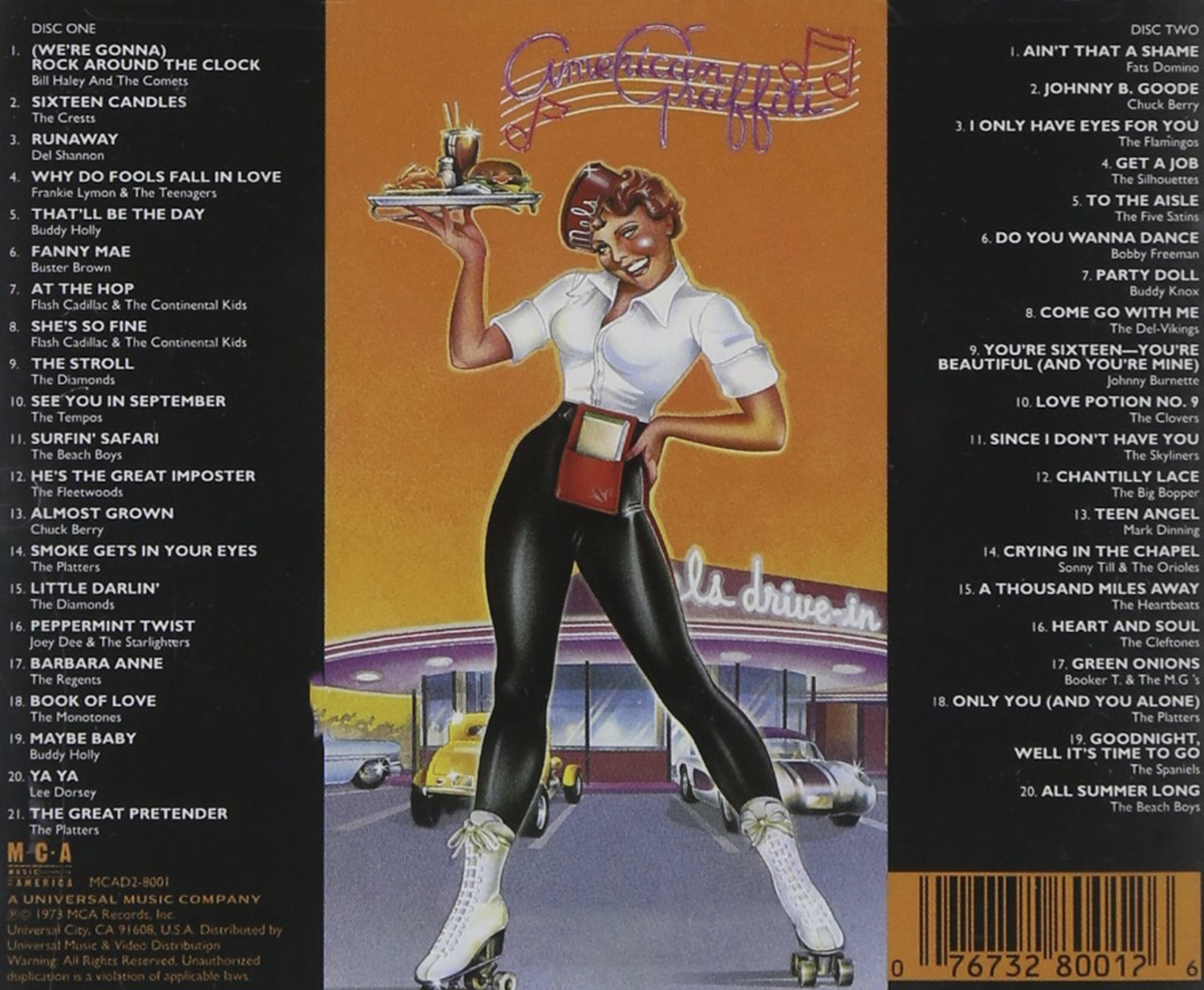

My boss was Brian Fox, and his wife, Kara, had a greeting card company in the same building. One day Kara phoned me to tell me she was not going to get back to the office in time for an appointment and asked if I could stand in for her. I was to simply meet with an illustrator and review his portfolio for possible freelance greeting card assignments. The illustrator, who I’d assumed would be a young, inexperienced artist like myself, turned out to be David Willardson, one of the kings of the California airbrush art movement, and at the top of my list of contemporary illustration heroes! For those who don’t recognize the name, you probably at least know one of his most famous paintings, the American Graffiti soundtrack album cover that features a car hop on roller skates holding a tray of burgers and fries with Mel’s Diner gleaming in the background. But Dave’s work was ubiquitous in the ’70s and ’80s, and I was one of his disciples.

While I tried to play it cool and act like I was remotely qualified to review Dave’s portfolio, he noticed one of my movie posters, framed on the wall in my work area. He was impressed by it and asked if I was able to take on occasional freelance jobs. I discovered that Dave wasn’t just a lone freelance illustrator, but owned and operated a small studio where he worked with another illustrator, Calvin Patton, and occasional freelancers. I told him that my employment with B.D. Fox didn’t preclude taking on outside jobs when work was slow, so he invited me to visit the studio, whereupon he gave me a freelance assignment. After a few such jobs, Dave invited me to work at his studio full-time, and I reluctantly left B.D. Fox because I knew that Dave was not just offering me a job, but also an education.

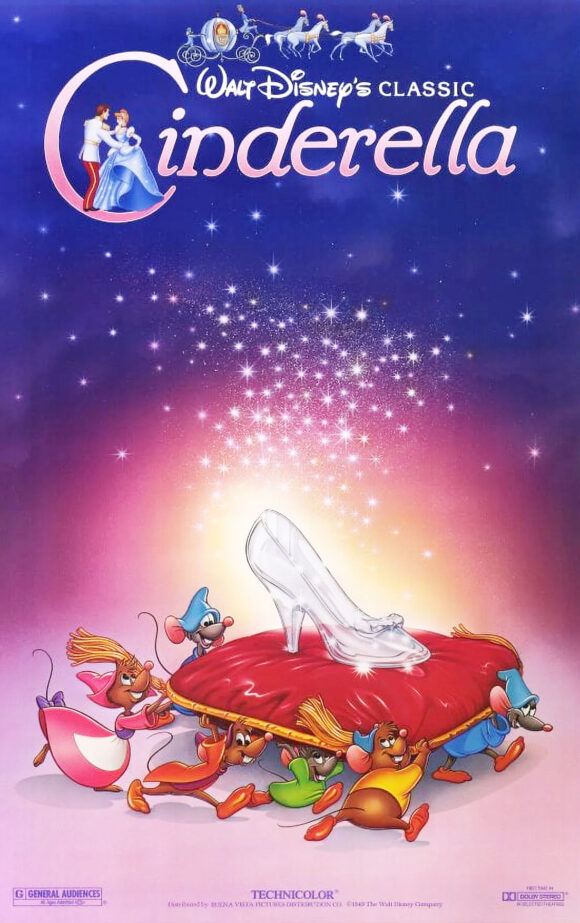

At the studio, Willardson Associates by name, we produced all sorts of illustrations for different products, mostly glorified photorealistic work for major clients such as Nestle, Maxell, and Curtis Mathes. But one day we got a commission from the feature film marketing department at Disney. They were going to give the 1950s animated feature Cinderella a theatrical re-release and needed a few one-sheet lobby poster illustrations. By then, Dave knew that I was into comics and animation, so the Cinderella job landed on my desk.

Under Dave’s direction, I did a teaser poster, which was rare for a re-release, followed by a main poster that featured most of the characters and the iconic castle. Disney loved the work, and began to give us one assignment after another. Back in the ’80s they would re-release a few of their classic animated films into theaters every year, along with a brand new one, before putting them out on video, and I became the “cartoon guy” in the studio. In addition to Cinderella, some of the posters I worked on were Oliver and Co., The Rescuers Down Under, Roller Coaster Rabbit, The Prince and the Pauper (a Mickey Mouse featurette), Peter Pan, The Jungle Book, Bambi, Lady and Tramp, etc.

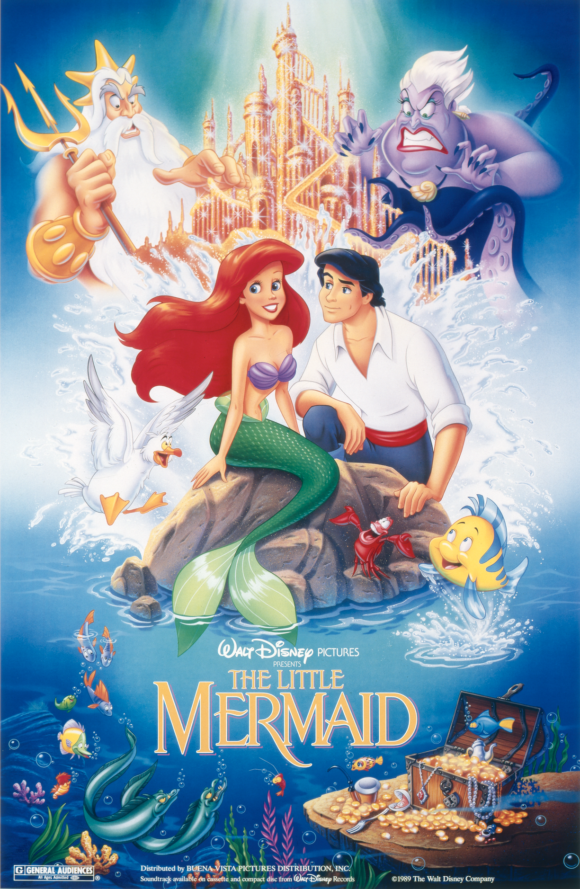

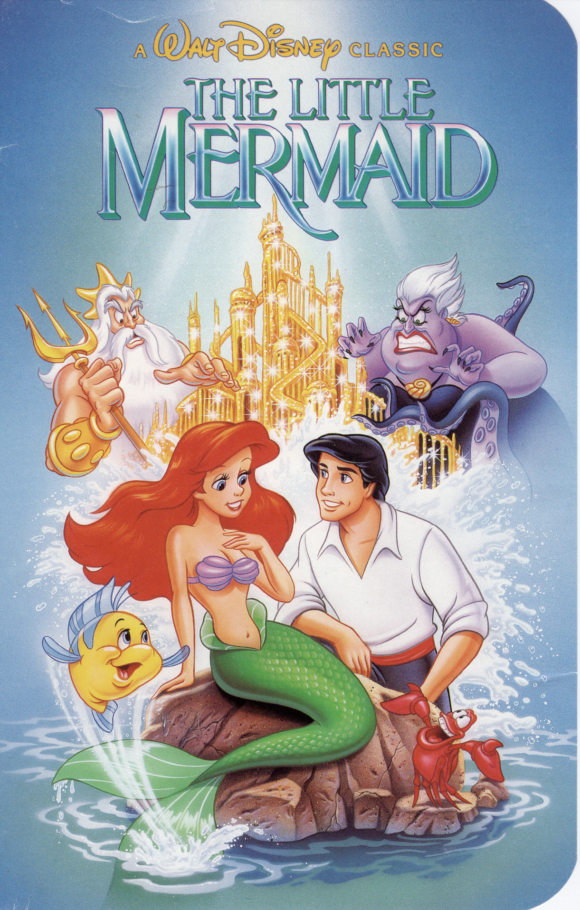

One poster assignment was for the upcoming feature, The Little Mermaid, and though some people think the scandal arose from that image, it’s not the case. The poster was a success and Disney loved it. But then a few months later, an art director from Disney Home Video called to make an appointment with Dave to discuss a new assignment, artwork for The Little Mermaid video release.

Dave met with the art director who brought with him a finished painting by another artist. It featured an underwater scene with Ariel and the fish musicians from the Under the Sea musical number. It was quite nice, but the art director explained to Dave that his boss really liked the movie poster that we did, and he was told to find the artist and get him to paint a similar image.

Understand that Disney Home Video was in a different building in another part of town from Disney Feature Film, which was housed on the studio lot. Let’s just say it’s a big company and the employees don’t all know each other or have any idea how to reach people in other departments. At least, they apparently didn’t then, because it took the art director some time to find out who did the poster art, and by then, they were very close to their print deadline with very little time to generate an entirely new piece of art.

So, Dave took me aside and asked if I would be willing to work over the weekend and maybe pull an all-nighter to get the art done. It would be a boon to the studio to start getting work from the home-video branch of Disney in addition to the theatrical work we were already getting. Of course, I agreed and got right to work with only a few days to complete the assignment. The art director sent over a layout and a sketch, and I worked from the sketch for the main characters. I used my drawings of Triton, Ursula, and the castle from the poster, since they were unchanged in the layout.

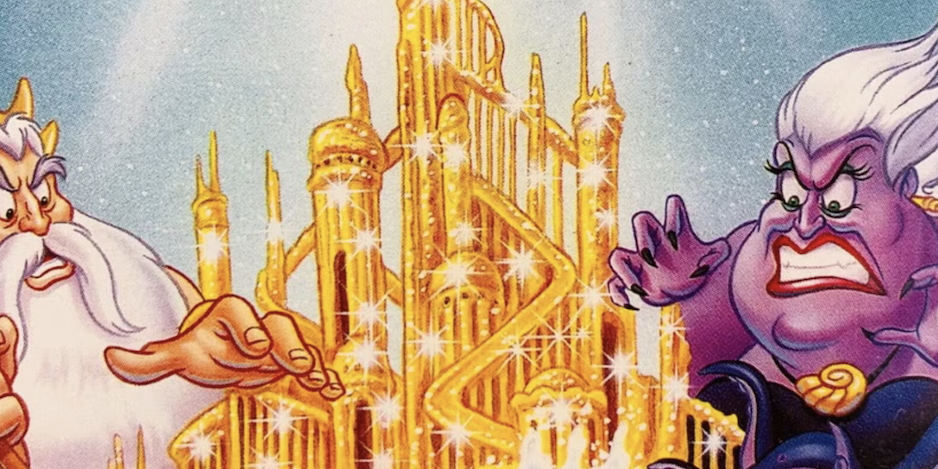

Having such an unusually short amount of time before the print deadline, I guess my pacing was a bit off, and I remember spending most of my time working on the characters before realizing I needed to focus on the background elements. I probably painted the castle at around 3 a.m. the day it was due, so although the drawing is the same as in the poster, the rendering is rushed and many fine details were left out.

But I finished the art by dawn and it went to Disney and then to the printer. Nobody noticed that one tower in the coral castle closely resembled male genitalia. Not, that is, until a man in Arizona brought a copy of the tape home from the video department of an Albertson’s supermarket, noticed the phallic image, and pointed it out to his wife.

She was not amused, and stormed off to the store to demand that they take the video off the shelves. Apparently, the store manager refused, but they did arrive at a compromise. I know this because Dave, Calvin, and I watched an ABC News report in the studio on the evening that the story of moral depravity broke, in which a pan shot showed a shelf full of video tapes clad in brown paper lunch bags with “Little Mermaid” scrawled on each one in magic marker. The scandal was off and running!

Around this time, I had completed the illustration for the Prince and the Pauper poster, and Dave took the art to Disney for review. He returned to the studio a bit shaken because while waiting to show the painting to the art director, he overheard him discussing the Mermaid scandal and saying to an associate, “If I ever find out who did it, I’ll make sure he never works for Disney again!”

At this point in time, I believe at least half of the work that came into the studio was from Disney, so the prospect of losing their account was a huge deal. Dave was faced with a dilemma; he could keep his mouth shut, in which case the art director might discover by other means that the art came from Dave’s studio and stop taking his calls, or he could admit that his studio created the art and have possibly his only opportunity then and there to defend it. He chose the latter, but told me that it took him 20 minutes of arguing his case before the art director finally relented and said he believed that the phallic tower was not painted on purpose.

As I previously mentioned, the initial rumor reported that a disgruntled Disney artist was the culprit, and it grew from there. I was in a comic shop one day and heard two people talking about the scandal. One told the other that the artist was fired because Disney discovered he was gay. The next version I heard was that he was fired because he had AIDS (remember, it was the ’80s.) And more followed. The final variant that I heard before the story settled into its status as a classic urban legend was that the Disney artist was fired for being a gay, AIDS-ridden Satan worshiper who was caught conducting demonic rituals in the office after hours.

I’m not kidding.

So, this brings us back to the question: Is any part of the urban legend true?

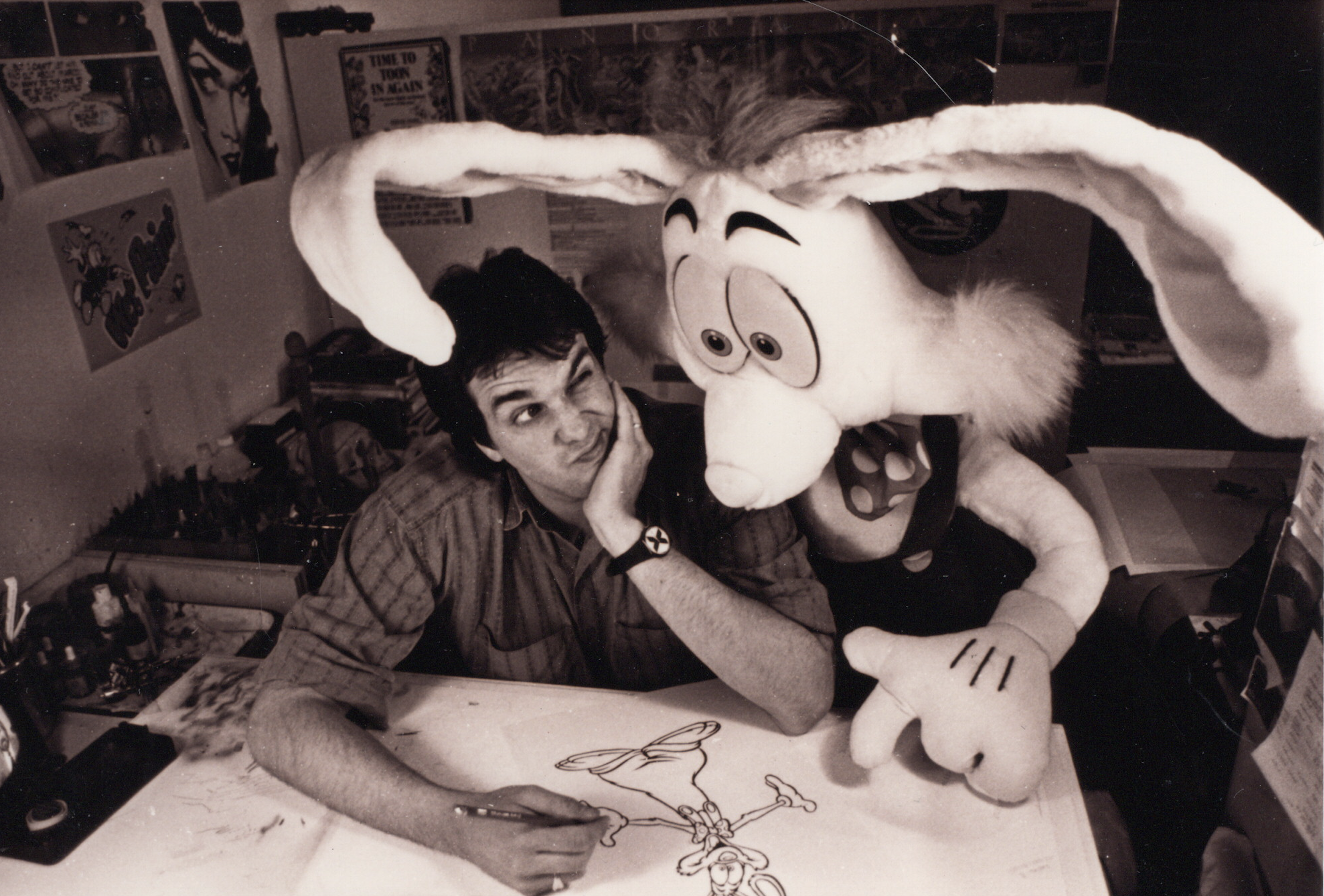

Roger Rabbit and me.

First of all, I was not a Disney employee, so it would have been impossible for them to fire me. No firing equals no disgruntlement. So even the initial story is totally false, and for the record I’m not gay, I never had AIDS, and am not now nor have I ever been a Satan worshiper.

But let’s say it was not an act of retribution but a simple prank. Given how much Disney work I was doing and how much of my livelihood came from the House of Mouse, why would I jeopardize my job for a practical joke? Obviously, I wouldn’t. In addition to those other things that I’m not, I am not stupid. Plus, there’s the fact that I’ve always loved drawing and painting Disney characters. It’s been one of the greatest joys of my career, so I definitely would not have risked putting an end to that for a joke.

The happily ever after ending to the story is that Willardson Associates continued to get work from Disney. They ultimately believed that we had no intention of putting the image of a penis in the box art of a family video. And I continued to paint Disney images until The Simpsons came calling and I reluctantly left Dave’s studio.

As for the legend, it lives on. As recently as last year during the excitement surrounding The Little Mermaid’s 35th anniversary, I read a social media post by a Disney animator who was still propagating the tale of a fired Disney employee who took vengeance on the Mouse and painted a penis into a children’s video package.

As with all urban legends, I’m sure the story will live on long after I’m dead, and then who will be here to tell the true story of the great Disney “Phallus in the Palace” scandal? Well, now that you’ve read it, I’m looking at you, dear reader!

—

Want more MORRISON MONDAYS? Come back next week! Want a commission? See below!

—

MORE

— THE RAMONES, FUTURAMA and a Classic Freaky 1950s Comic Book Ad. Click here.

— A FUTURAMA NEW YEAR: The Fine Art of Producing a Fab Calendar. Click here.

—

Eisner winner BILL MORRISON has been working in comics and publishing since 1993 when he co-founded Bongo Entertainment with Matt Groening, Cindy Vance and Steve Vance. At Bongo, and later as Executive Editor of Mad Magazine, he parodied the comics images he loved as a kid every chance he got. Not much has changed.

Bill is on Instagram (@atomicbattery) and Facebook (Bill Morrison/Atomic Battery Studios), and regularly takes commissions and sells published art through 4C Comics.

January 13, 2025

“Phallus in the Palace?!” Oh, LOL! Love it! I actually remember hearing a bit about this when it was happening way back when. Makes me think of 40 years ago when a college buddy of mine who was pre-med spent time in a psychology class discussing phallic symbols and he wouldn’t shut up about it!

January 13, 2025

Yeah, this was quite a, er, “piece” back in the day – how cool to know the truth, and the artist himself!

January 13, 2025

It also reminds me of the classic “C-3PO Dick Shot” by a “disgruntled” Topps bubblegum cards employee.

January 13, 2025

I don’t recall the C-3PO one but I do recall the Roger Rabbit topless shots on the laser disc version. So getting back to Disney, even if it wasn’t actually what a lot of folks were seeing, was the artwork changed going forward?

January 13, 2025

Look it up. It was, maybe, the fourth series of Topps’ Star Wars trading cards. Someone at the company airbrushed a phallus on C3PO for one card. That card was later changed back to the original photo. I actually have one of the original altered cards.

January 13, 2025

I of course heard the rumors about this, and I’m glad to know the truth, and know it was you Bill who did this amazing work during Disney’s second “Golden Age”. Beautiful stuff! Now, do you also happen to the be the disgruntled Disney animator who snuck some female genetalia into Who Framed Roger Rabbit? 😉

January 13, 2025

This is total BS they absolutely knew it.

I’m glad everyone is trying to save face over a failed production bonus.

January 13, 2025

Lot of good people fell on the airbrush sword for this I just wish all of the ones who lost their future didn’t have to read this!

January 13, 2025

As an illustration student in the 80s, and a budding illustrator in the early 90s, this was MUCH talked about in my circles… It is awesome to know the TRUE story, and how it was all just a tempest in a teacup. Thanks, news media! You never fail to disappoint.

January 13, 2025

Ok, I read the whole story but I’m still not sure of the reason. It was a prank? It didn’t really much go into why.

January 13, 2025

“Fletch”, I think Bill is saying he was the artist who painted the work in question and so would know the story behind it all. Not a prank or even on purpose. Basically folks saw what they wanted and from there it took on a life of its own and became an urban legend. That’s how I took the article.

January 13, 2025

I thought the story was laid out very clearly. I’m not sure what was confusing for you. I said it was definitely not a prank and not done on purpose and gave the reasons why for both.

March 18, 2025

The way this line reads:

“But let’s say it was not an act of retribution but a simple prank.”

It does kind of sound like you were saying it was a simple prank… Perhaps you meant to say:

“But let’s say it was not an act of retribution nor a simple prank.”

July 24, 2025

It’s really cool to know the real story now. I work in theater and have been told that many theater painters hide little details like this in their huge background paintings. Silly stuff – like penises. Really. Because no one’s ever gonna notice and because their line of work can get tedious. So I’ve always assumed it was kind of that.

But now after reading your story and comparing the movie and VHS paintings I can tell that it’s basically a “problem” of missing shadows combined with a little too strong outline. And I completely get how that can happen when you’re short on time. Thanks for sharing!

February 13, 2026

He was vague about whether he was the one who painted the castle. I’ve gone back to the one paragraph when he talks about the castle and re-read it several times. I can see why he’s reluctant to take credit for painting it. “It was 3 am. I left out some fine details.” Yeah, but did you know you were painting a penis?

December 25, 2025

No, he said he was just tired lol. Yeah right.

January 13, 2025

What a fun story that I am so happy to have read.

My grandmother’s nephew was an animator at the Simpsons back in the late 90s. I got to tour the Film Roman studio around that time. I wonder if you were there at that time.

January 13, 2025

I worked directly for Matt Groening, so though I know and have worked with several Film Roman artists, I didn’t actually work there.

January 13, 2025

I’m glad that I finally got to tell your story in print for the first time in my Little Mermaid Bookazine last year!

February 27, 2025

I’m glad to read this. And to know that the real story makes the kind of sense i had always supposed: why on earth would somebody do that on purpose? Nice conspiracy theory, but, really!

One question: Does the phallus in the palace hold the brew that is true?

January 14, 2025

Great story, Bill. I too work in a business where sometimes you are asked to work late on little sleep and sometimes things don’t end up done as well as you would like. This is what happens when you rush people!

January 15, 2025

At that time, I worked as a Disney staff artist in an office building in Burbank off Disney’s studio lot. The art director in my dept showed me a layout sketch he had drawn for that Little Mermaid video box cover. The palace in the background was amorphous, and he explained your story to me. I’ve stayed up many a night finishing drawings that had to rushed for a deadline, so I completely get it. Every time I hear this urban legend, I know the truth. Really enjoyed your post!

December 1, 2025

Thanks so much, Laureen! I had lunch with that art director (I’ll keep his name private as well) in recent years, and we had a good time, though he told me that he was in hot water because of me at the time of the scandal.

January 20, 2025

It’s wild that this story developed into a tale of a disgruntled employee sticking it to the man. I was seven years old and even then I was old enough to understand that of course nobody intentionally put a penis in the Little Mermaid box art, and if you see one there that says more about you than it does about the artist.

February 6, 2025

I think the artwork is beautiful and I never even saw it until someone told me out was done by a disgruntled employee of Disney because they didn’t pay the artists enough. The same went with “teenagers take off your clothes! In the Aladdin movie, balcony scene, which WAS there on the VHS until they wiped it off the DVD. I’m glad to know that my favourite animation, The little mermaid, did not in fact have a penis drawn into the castle and I will spread the truth. Thanks for your beautiful artwork of Ariel and friends. Any chance of seen autograph? I’m literally obsessed with The Little Mermaid animation. I think it’s the most beautiful fairy tale and I love Disney’s take on IT SO much.

December 1, 2025

Thanks, Steve! For an autograph, see me at a local comic convention. I do several per year around the country, and sometimes outside the US.