A BIRTHDAY SALUTE to one of comics’ most beloved creators…

By SCOTT TIPTON

—

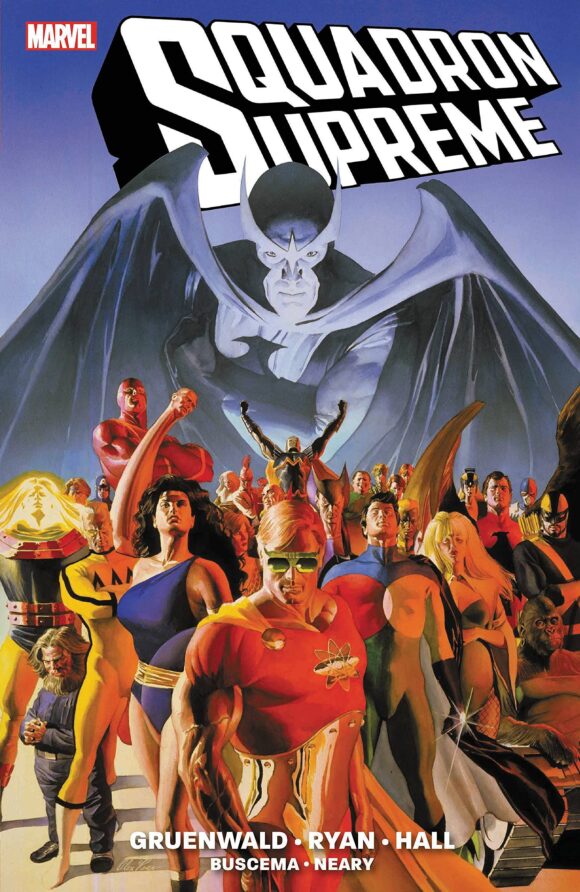

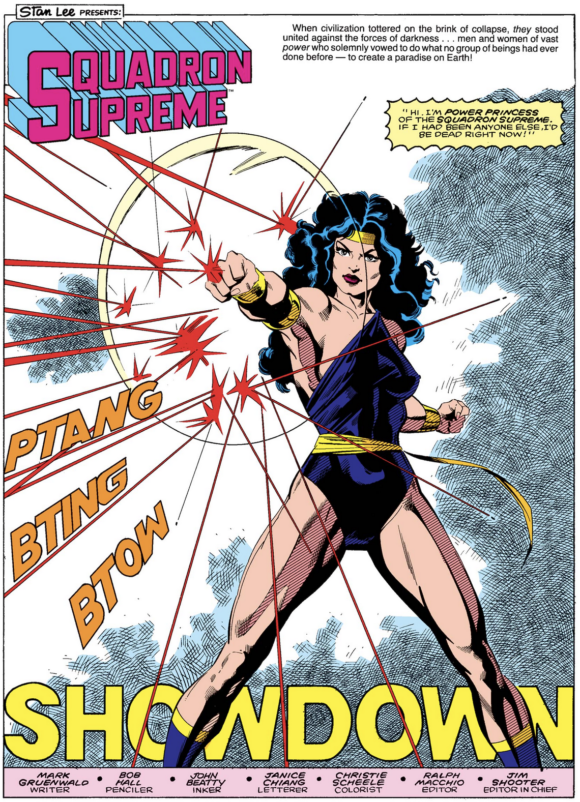

Late Marvel Comics editor Mark Gruenwald was born 69 years ago on June 18, 1953. With Da Gru’s induction into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame rapidly approaching, it seemed like the perfect time to take a close look at the work he was proudest of: Squadron Supreme.

SPOILERS BELOW!

—

In 1985, longtime Justice League of America fan Mark Gruenwald finally got to write the characters he’d been wanting to write his entire professional life.

Sort of.

You see, while Gruenwald still worked for Marvel, and therefore didn’t have access to the JLA, Marvel did have the Squadron Supreme, which was for all intents and purposes the next best thing. Back in 1971, then-Avengers writer Roy Thomas had created the Squadron Supreme as a kind of tongue-in-cheek “tribute” to the Justice League, having them brought from their own parallel Earth by the cosmic gamesman the Grandmaster to battle the Avengers. (All this took place in Avengers #85, for those of you who want to look this up in your Epic Collection books. (And if you don’t have the Epic Collection volumes yet, why don’t you?)

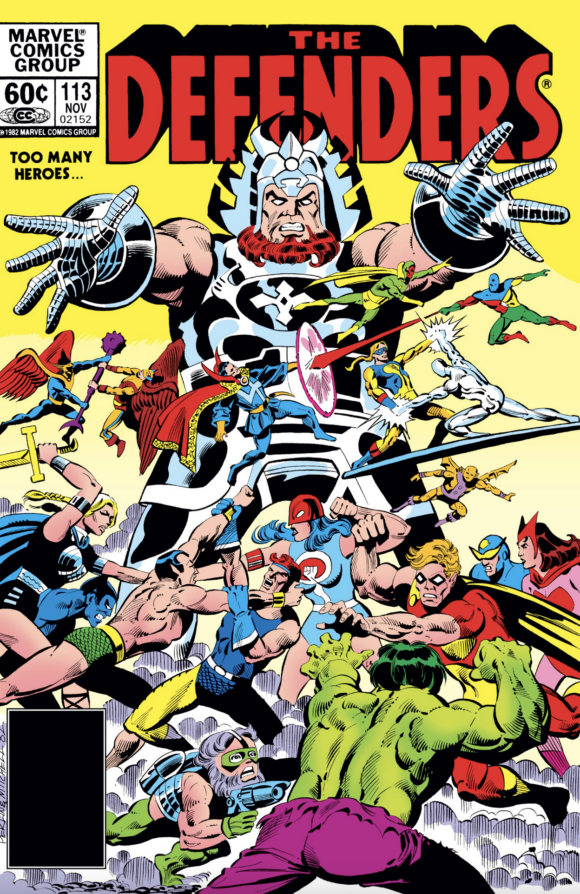

The Squadron Supreme made several appearances over the next few years in Avengers and other books, until, in their 1982 appearance in Defenders #112-115 (by writer J. M. DeMatteis and artist Don Perlin, an underrated team if there ever were one), their ranks had swelled to 12, an almost note-perfect reflection of DC’s JLA.

To be precise, Hyperion, Nighthawk, Dr. Spectrum and the Whizzer stood in for Superman, Batman, Green Lantern and the Flash, while Power Princess, Amphibian, Golden Archer and Tom Thumb were the Squadron’s versions of Wonder Woman, Aquaman, Green Arrow and the Atom. Blue Eagle, Lady Lark, Arcanna and Nuke were the analogues to Hawkman, Black Canary, Zatanna and Firestorm.

The Defenders story featured Nighthawk bringing the Defenders to his parallel Earth to help fight his teammates in the Squadron, who had been mentally controlled by an alien creature known as the Overmind. The villain used the Squadron’s muscle and his own mental powers to take control of the world.

The Defenders (at one of their most formidable moments, with a power-heavy roster that included Dr. Strange, Sub-Mariner, the Hulk, the Silver Surfer, the Vision, the Scarlet Witch and the Beast, as well as the usual Defenders hangers-on Valkyrie, the Gargoyle and Daimon “the Son of Satan” Hellstrom) managed to free the Squadron from the Overmind’s control, and the two teams vanquished the bad guy. The Squadron’s Earth was free again. However, it was also a shambles, with its resources depleted, its people confused, and under no real leadership.

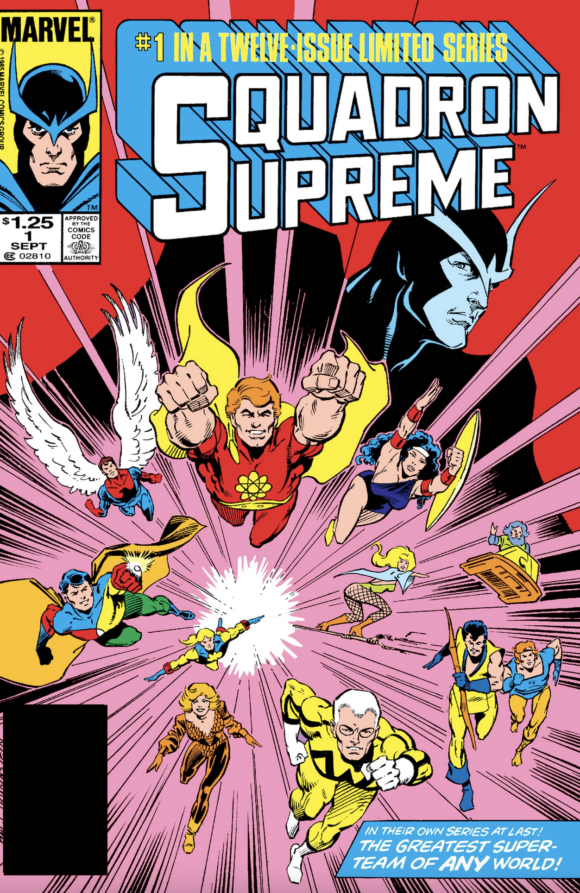

This was where Gruenwald came in, with the first issue of his 1985 12-issue maxiseries Squadron Supreme.

The series (with art by Bob Hall and Paul Ryan) opens with the Squadron struggling just to keep their world together, working to stem looting, crowd control and riots in the wake of the Overmind’s departure. In the face of global anarchy, the Squadron’s leader, Hyperion, proposes the team take a far more active role in the world, to “abolish war and crime, eliminate poverty and hunger, establish equality among all peoples, clean up the environment, cure disease and even cure death itself.”

Nighthawk objects to the plan, believing the Squadron’s decision to take control of the world is no better than the Overmind’s and still amounts to the elimination of man’s free will. The team puts it to a vote, with only Nighthawk and Amphibian voting against Hyperion’s “Utopia Project.”

In response, Nighthawk resigns from the Squadron, and even considers assassinating Hyperion to prevent his plans from coming to fruition. Nighthawk is unable to bring himself to murder his closest friend, and stands aside while the Squadron announces its decision to assume global authority; if the plan doesn’t work within one year, they would give up their power. As a gesture of good will, the Squadron Supreme unmasks on worldwide television, ushering in a new age of Earth under control of the superman.

With this first issue, Gruenwald put readers on notice that this would be a series unlike anything else Marvel or DC was publishing. No longer just costumed superheroes slugging it out with the bad guys, this book would show the Squadron struggling with new conflicts, like feeding and protecting an entire world. Do the best of intentions justify an immoral act? The series would look at this question over and over again, on the largest and smallest of scales.

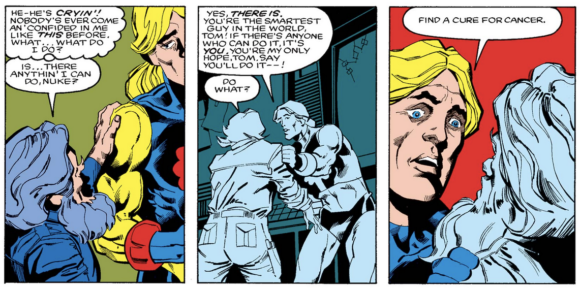

The very next issue showed just a hint of the moral ambiguity to come, with the dilemma of Nuke, the Squadron’s nuclear-powered young member, whose parents are dying of cancer. A consultation with Tom Thumb, the Squadron’s resident genius scientist and inventor, reveals that Nuke’s powers have increased so much that he had been unknowingly putting off radiation constantly, as a result poisoning his parents.

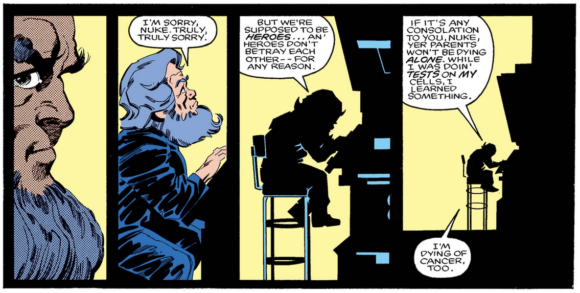

The desperate Nuke begs Tom Thumb to find a cure for cancer, and when he fails to do so, Tom considers making a deal with the Squadron’s time-travelling enemy the Scarlet Centurion, who offers a cancer cure from the far future in exchange for Tom’s poisoning of Hyperion, but Tom refuses, unwilling to betray his friends for what the Centurion taunts as “the greater good.” Tom breaks the news to Nuke that he was unable to find a cure, and when a furious Nuke flies out, blaming Tom for his parents’ imminent death, Tom mumbles his own startling revelation:

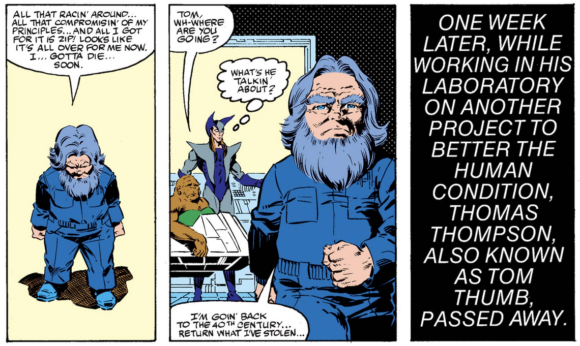

Eventually, Tom’s ethical rigidity will fail him, and he’ll return to the Scarlet Centurion’s future, this time to steal the cancer cure, only to discover that the “Panacea Potion” is little more than penicillin and vitamins – centuries of eugenics had bolstered the immune systems of future humans, so little more was needed to keep disease away. Resigned to his fate, Tom returns what he’s stolen to the future, and the issue ends with a spare but chilling coda, far more powerful and affecting than if Gruenwald and Ryan had provided a maudlin death scene.

Although standing by one’s moral code is tough, as the death of Tom Thumb illustrates, those who violate it gain little in doing so.

One of the Squadron’s first moves is to replace all guns in police departments and the military with non-lethal substitutes, and to strongly encourage gun control among the citizenry, to the point of shutting down all gun manufacture in the U.S. While the Squadron deals with the uproar from the population, they dispatch Dr. Spectrum to track down the absent Nuke, who’s been missing since his argument with Tom Thumb.

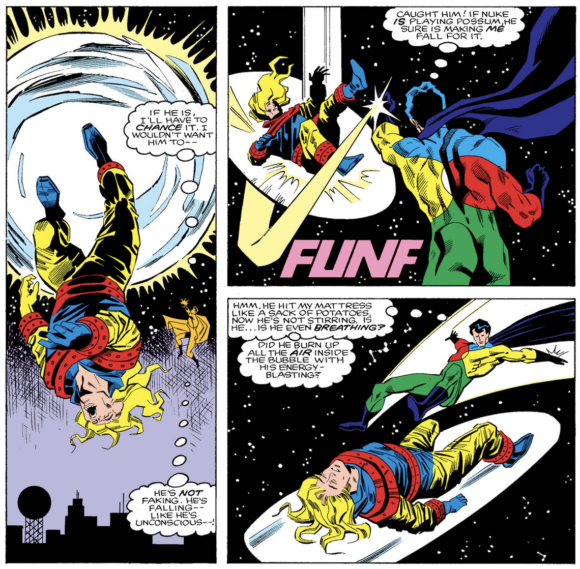

Spectrum tracks him down at his parents’ graveside, and the inconsolable Nuke lashes out, blasting the grounds and threatening to return to the Squadron’s HQ and murder Tom Thumb before anyone can stop him. Nuke and Doc Spectrum engage in a heated airborne battle, and when Spectrum traps Nuke in an energy bubble in the hopes containing the radiation, he soon discovers that Nuke quickly burned up all the oxygen inside while trying to escape, and died of asphyxiation.

The guilt-ridden Spectrum refuses to use his powers against anyone following the accidental death, despite the Squadron absolving him of any wrongdoing. Do the best of intentions justify an immoral act? Even as early as Issue #3, Gruenwald begins subtly reinforcing his overall theme.

The point is brought into even sharper relief with the unveiling of Tom Thumb’s latest invention: the Behavior Modification Program, which can change brain cells to replace negative tendencies with positive ones, in essence reprogramming the personalities of criminals and transforming them into law-abiding citizens. Again, this causes some friction within the Squadron, as Amphibian and Arcanna object to the use of the device as an assault on free will. After another vote, the two are overruled, and plans begin to use the machine on the prison population.

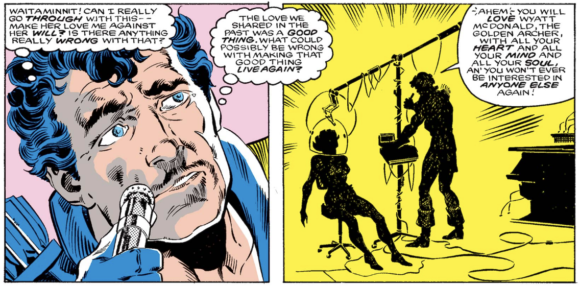

Unfortunately, the first subject of the machine is one of their own. When Lady Lark turns down the Golden Archer’s proposal of marriage, and instead ends the relationship, the Archer secretly uses the machine on her, making her fall in love with him again, this time permanently.

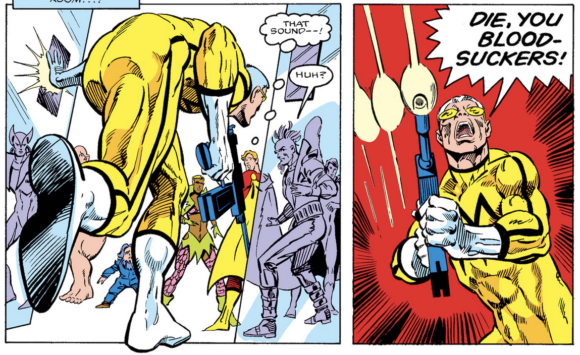

Not long after, the Archer is kidnapped by the Squadron’s longtime enemies, the Institute of Evil, and tortured into revealing all he knows about the Behavior-Mod device. The Institute kidnaps the families of the Squadron members in order to force them to submit to reprogramming, but the Whizzer escapes, and in a note of bitter irony, runs right to where all the guns were confiscated for dismantling, grabs the most lethal assault weapon he can find, and heads back to kill his families’ kidnappers.

Luckily, the Squadron was unable to be reprogrammed thanks to Tom Thumb altering the machine (due to his own suspicions about the Golden Archer), and they stop the Whizzer from murdering the supervillains, but it illustrates how much easier it is to make a moral stand when you personally have nothing on the line. When push came to shove, the Whizzer’s moral authority vanished right down the barrel of a gun.

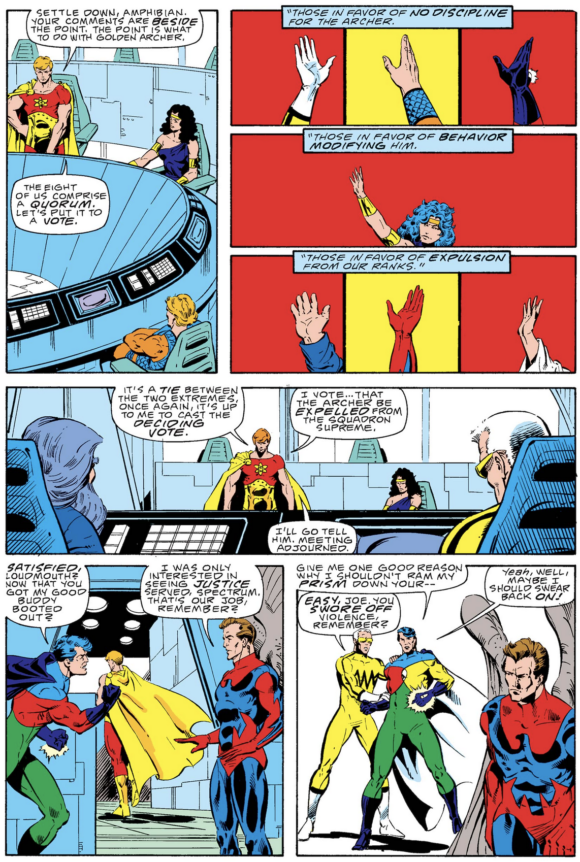

The Institute of Evil are themselves reprogrammed and made members of the Squadron Supreme, to help sustain their dwindling ranks, just before the loss of three more members, when the Blue Eagle accuses the Archer of using the Behavior-Mod device on Lady Lark. When confronted, the Archer confesses, and the Squadron debates what to do about it, finally deciding to expel him from the team.

The now brain-addled Lady Lark quits the team to be with the Archer, while the completely disillusioned Amphibian, furious that his unheeded warnings about the immorality of the Behavior-Mod device has led to this, destroys all the Behavior-Mod machines and erases all of the plans before abandoning the team, returning to the ocean permanently. Again, the moral ambiguity of the Squadron’s crusade is brought to the forefront.

To digress for a moment, another interesting facet of the book is how Gruenwald takes details about the JLA characters that have gone unnoticed for years and carries them to a logical if unexpected conclusion. We’ve already seen an earlier example, in the Whizzer’s choice to protect his family over loyalty to the team, a choice that JLA writers never forced the Flash to make.

For another example, consider the Squadron’s Power Princess. Much like Wonder Woman, Power Princess is an immortal “Amazonesque” warrior queen, who came to America in the 1940s and fell in love with a handsome American soldier. The difference here, though, is that while the soldier aged, Power Princess did not, and so the young, vital gorgeous superheroine remains married to an 80-year-old man, putting a harsh, realistic spin on the Wonder Woman/Steve Trevor relationship.

The Squadron’s “Utopia Project” continues, issuing all citizens personal force-field belts of the late Tom Thumb’s invention, allowing all to live free from fear of crime, while using Tom’s death to publicize his final creation, the Hibernaculum, which will hold the dead or near-dead in a state of suspended animation until a cure is found for whatever disease struck its occupant.

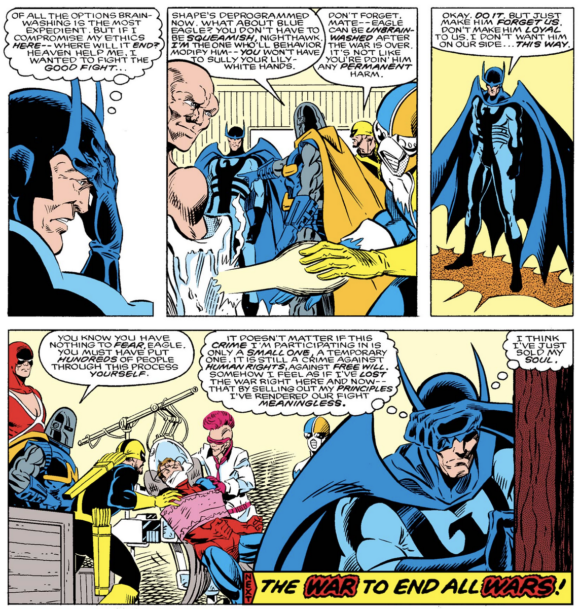

While the Squadron has been working on its crusade, ex-member Nighthawk has been scheming to bring the Squadron down from within, recruiting previously unknown superhumans to his cause and planting them as the Squadron’s newest members. (Luckily for Nighthawk, the Squadron hasn’t completely abandoned its sense of right and wrong, as a motion to preemptively reprogram the new recruits is outvoted.) Once the new members are in place, Nighthawk has them steal the plans to the Behavior-Mod device, which he hands over to Master Menace, the Squadron’s greatest foe (think Lex Luthor).

Menace then creates a machine to undo the Behavior Modification, which Nighthawk uses to restore the former Institute members-turned-Squadron recruits to their old, criminal selves. Unfortunately, in the process, Nighthawk’s base is discovered by Squadron member Blue Eagle, and Nighthawk has to make a choice: Let the Eagle go and risk losing his war with the Squadron before it’s begun, or use the Behavior-Mod device on him, and become the very thing he’s fighting against. Nighthawk makes his choice:

Do the best of intentions justify an immoral act?

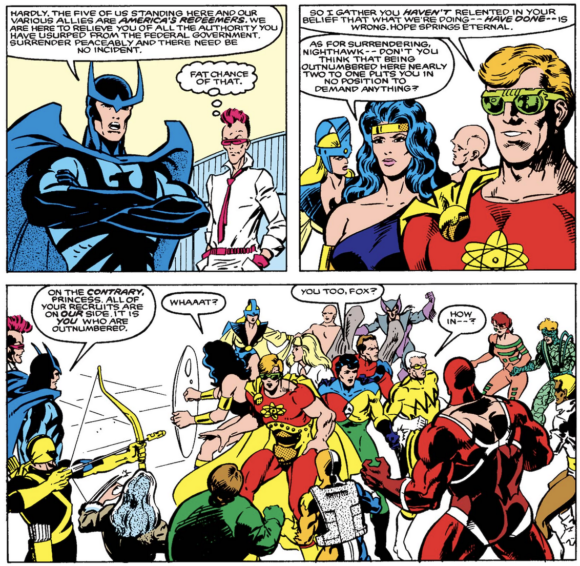

Nighthawk and his “redeemers” confront the Squadron on their own turf, reveal that all their new recruits are in fact working for him, and demand that the Squadron relinquish all authority over the world.

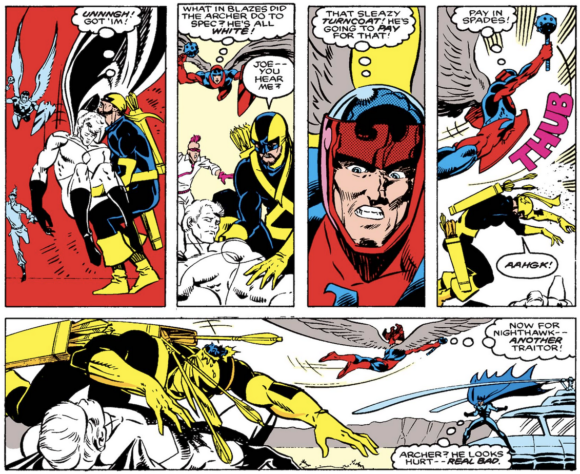

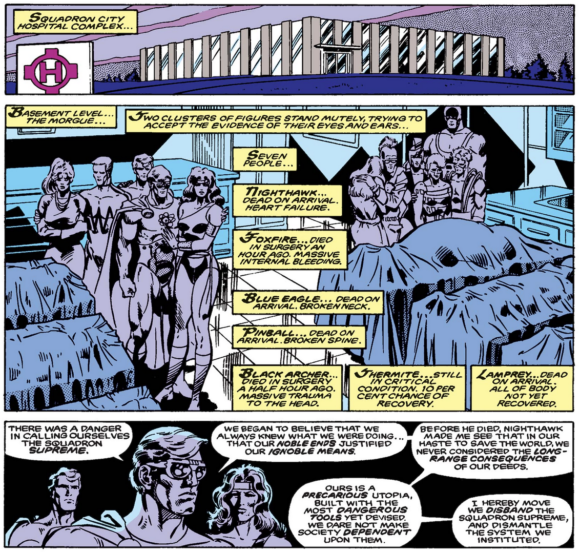

The Squadron, now reduced to its remaining original members and vastly outnumbered, still refuses, and what follows is one of the more brutal and unforgiving fight sequences that Marvel had published up to that time. Unlike the usual superhero fight where no one really gets hurt, here the consequences are startlingly real. For instance, one shot from the Blue Eagle’s mace, and his former friend the Golden Archer is dead from massive head trauma (an ugly reference to the always heated feud between Hawkman and Green Arrow in JLA).

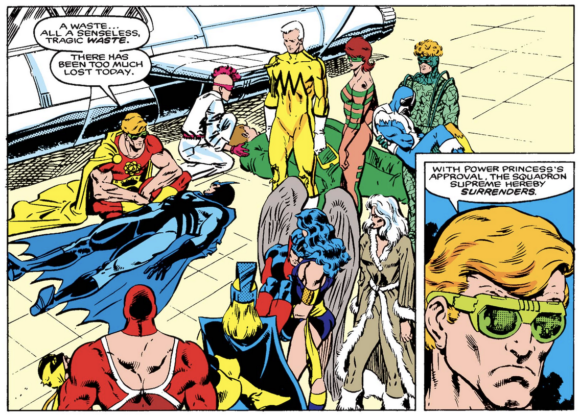

The Eagle himself is dead from a broken neck while trying to cushion his fall by landing on Pinball, a Plastic Man-type Redeemer, who also dies from a crushed spine. When the smoke has cleared, Nighthawk’s Redeemers have won, and Nighthawk explains to the downed Hyperion how he plans to return society to the imperfect but free status it held before the Squadron took control. As Nighthawk and Hyperion talk, one of Nighthawk’s Redeemers (who had fallen in love with Doc Spectrum) switches sides yet again, using her powers to induce a massive heart attack in Nighthawk, killing him instantly. This sets off another series of homicidal attacks between the teams, until a recovered Hyperion surrenders.

In his last moments, Nighthawk had convinced Hyperion that they hadn’t looked at the long-range picture, that even if they succeeded in bringing about Utopia, there was no guarantee that future generations wouldn’t subvert it to tyranny.

Standing amid the corpses of their fellows, Hyperion has finally realized what Nighthawk had warned him of 12 months before: that the noblest of intentions can’t justify immorality. Accordingly, the team resolves to disband and dismantle the Utopia Project.

While Squadron Supreme was in many ways years ahead of its time in its more serious tone and in some of the issues it raised, it was also a throwback to an earlier time in comics, with its firm stance that heroes should stand for something. This was a book that was about something, that wasn’t afraid to talk about issues of morality and personal ethics for fear of being considered “preachy.”

It’s probably Gruenwald’s best single work, and according to his widow Catherine Schuller, it’s the work he was most proud of. Go pick it up.

—

MORE

— MARK GRUENWALD, His Ashes and Me, by CATHERINE SCHULLER. Click here.

— COMIC BOOK DEATH MATCH: Watchmen vs. Squadron Supreme. Click here.

—

Scott Tipton is a regular 13th Dimension contributor and comics writer, best known for his work on IDW’s Star Trek series.

June 21, 2022

12 year old me loved this series. I agree it was Gruenwald’s best work. Sounds like it’s time to give it a re-read. I’ll probably appreciate it even more now.