REEL RETRO CINEMA: Aa-hooo! Werewolves of Spain!

—

New looks at old flicks and their comic-book connections…

UPDATED 10/6/25: It’s a full moon! It’s even a supermoon! It’s October! Perfect time to reprint this column from February 2018! Dig it! — Dan

—

By ROB KELLY

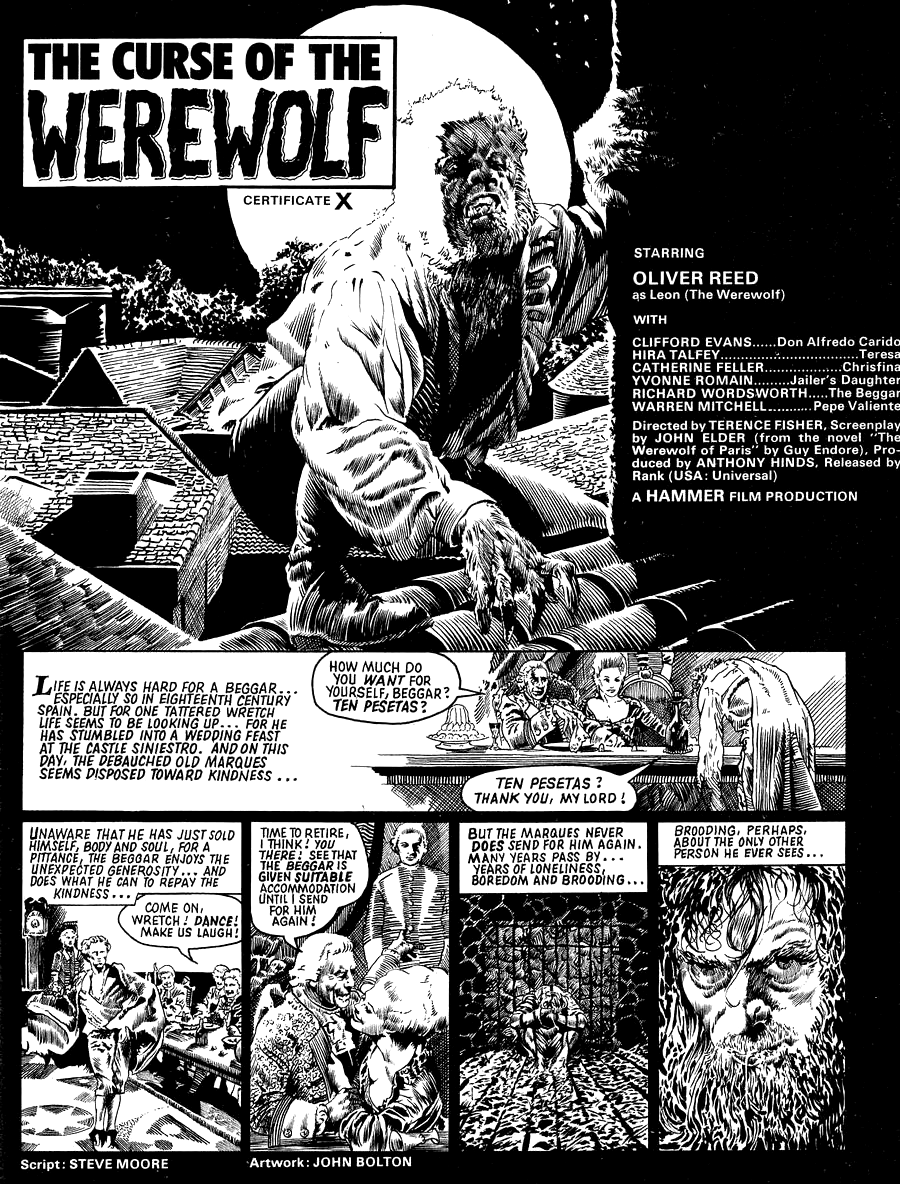

Can you make a werewolf movie without a werewolf? That was the question director Terence Fisher attempted to answer with 1961’s The Curse of the Werewolf, the only flick produced by the legendary Hammer Films to focus on this particular type of movie monster. Loosely based on the novel The Werewolf of Paris by Guy Endore, Curse features notorious wild man Oliver Reed in his first starring role as Leon, the poor soul afflicted by the titular curse.

Set in 18th century Spain, an old beggar (Richard Wodsworth) staggers into a wedding banquet thrown by the Marquis Siniestro (Anthony Dawson) looking for scraps of food or a coin or two. Siniestro is a cruel man (must be the name), and taunts the old man, treating him like an animal. After unwisely speaking up for himself, the beggar is thrown into a dank prison and promptly forgotten for 15 years. The beggar’s sole human contact is his jailer and his beautiful, mute daughter (Yvonne Romain), but when the young woman rejects the sexual advances of the aged and decrepit Siniestro, she is thrown in the same cell as the beggar. Driven mad by his imprisonment, the beggar rapes the young woman and then dies.

After she is released from jail, the young woman kills Siniestro (nicely done!) and runs into the forest. She is rescued by a kindly couple, Don Alfredo Corledo (Clifford Evans, who narrates the film) and his housekeeper Teresa (Hira Talfrey), and they discover the poor, young girl is pregnant. The baby is born on Christmas Day, which is considered unlucky because it was born out of wedlock. The young woman dies in childbirth, and the couple decides to raise the baby, named Leon, as their own.

Anthony Dawson

As the boy grows, it becomes clear that young Leon is troubled, at one point explaining to Don Alfredo that a hunting incident gave him a taste for blood, and he liked it. When some sheep are found slaughtered, a local dog is blamed.

Flash-forward a few years later, and Leon is now fully grown and leaves home to seek work at a vineyard. He falls in love with the vineyard owner’s daughter Cristina (Catherine Feller), but despairs he’ll never be allowed to marry her. One night he goes drinking with his friend, and when the moon rises he transforms into a werewolf (finally!) and kills two people. Realizing Cristina’s love prevents his changing into a monster, Leon makes plans for them to run away, but is stopped by the police, who arrest him of murder.

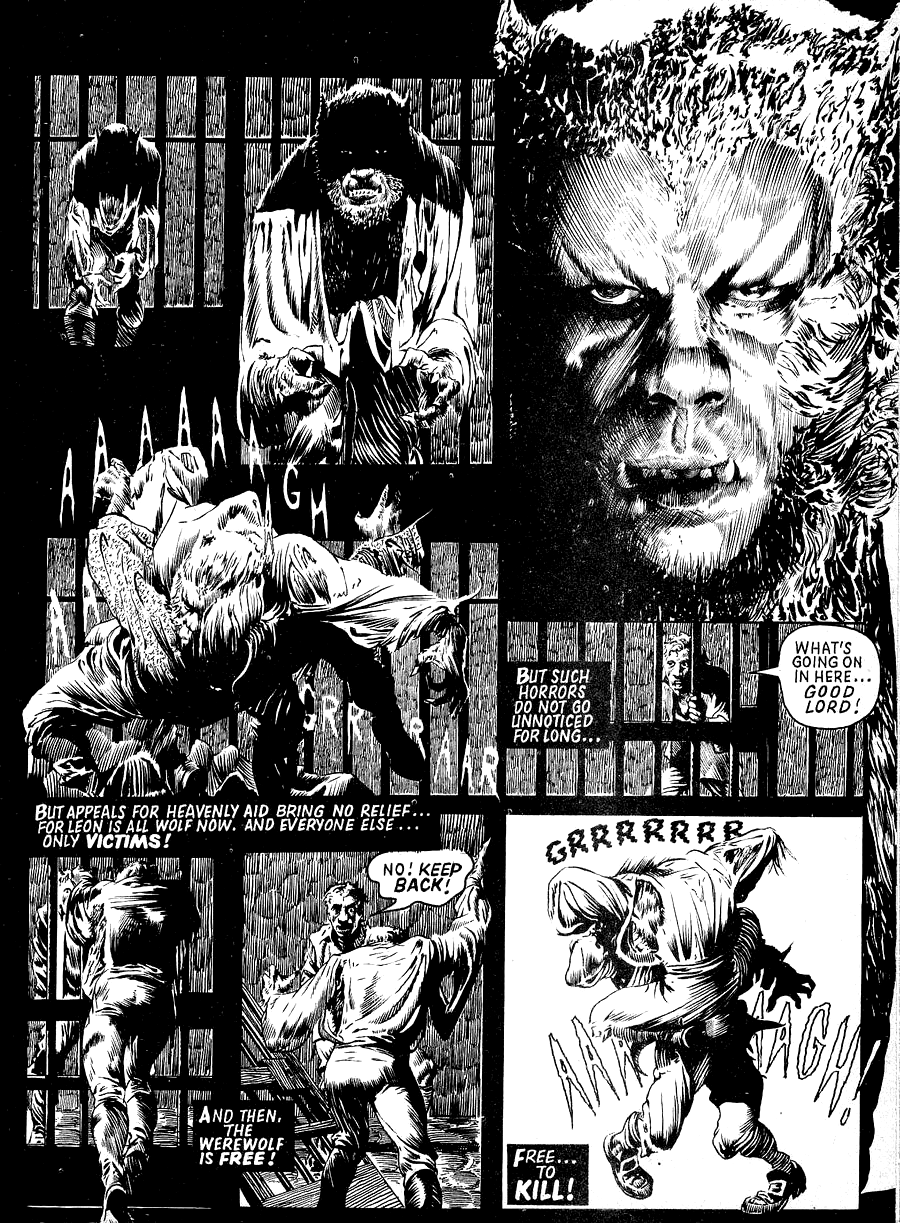

In jail, he begs the authorities to execute him before he turns again, but is ignored. That night, Leon changes again and goes on a rampage in the town square. The local townspeople surround Leon as he climbs a bell tower, and Don Alfredo is forced to confront his son and shoot Leon with a silver bullet, killing him. As Leon dies, his father covers him with his cloak. The End.

Oliver Reed as the werewolf.

Aside from the aforementioned fact that this was Hammer’s only werewolf movie, The Curse of the Werewolf is also unique in that it was distributed in the United States by Universal, who of course produced the classic 1941 The Wolf Man film (click here), not to mention 1935’s Werewolf of London, the first mainstream horror movie to feature a werewolf.

While certainly not a remake of either film, Curse borrows from both. The movie’s final scene contains elements from Frankenstein and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and the idea of the father being forced to kill his own werewolf-y son of course makes one think of Claude Rains and Lon Chaney at the end of The Wolf Man. What it borrows from London is its extreme minimalism when it comes to actually showing a werewolf.

Reed

Oliver Reed doesn’t show up until about halfway through this 93-minute movie, and then it takes another 15 minutes or so for the werewolf to finally appear and kill someone, and even then that is done entirely in silhouette. The monster make-up, which is suitably hideous and distinct from Universal’s classic Jack Pierce make-up, isn’t seen until the final sequence! Watching Reed/his stuntman scramble up the bell tower is really cool, but it’s all over much too quickly. At one point one of the nitwit townspeople throws a torch into a bay of hail near Leon, who promptly sends the giant ball of fire hurtling right back at them. Serves you right!

The opening scenes are quite effective—Anthony Dawson (who appeared in Dr. No, and played the very first Blofeld in From Russia With Love) is truly loathsome, especially when we see him as an old man. With his nearly gray and flaking skin (which we see him picking at, ewww!), Siniestro looks like a living corpse, as if his outside has finally begun to reflect his inside.

Yvonne Romain is one of Hammer’s most bodacious “scream queens,” her ample bosom pushed to the fore in nearly every scene she’s in. When she wakes up the next morning after being assaulted, the deep red gashes across her chest leave no doubt as to what happened. The fact that she is mute makes an effective, if perhaps unintentional, metaphor for how often women are forced into silence about sexual assault. These initial scenes don’t shy away from the relentless, grimy cruelty most people had (have?) to endure from the hands of the rich and powerful, and it sets the stage for what seems to be a potent second half.

Yvonne Romain

The problem for me with The Curse of the Werewolf is that second half—after Romain’s character dies but before the final reel reveal of the werewolf, it’s a whole lot of talk, talk, talk, with Reed sweating, glaring and emoting all over the place. I can appreciate horror movies that keep their scares minimal or subtle (It Follows, House of the Devil, Val Lewton’s filmography come to mind), but I had a hard time keeping interested in Curse, waiting as I was to finally see a frickin’ werewolf.

There are no such pacing problems with the comic-book adaptation that appeared in the January 1978 issue of The House of Hammer magazine. It runs 15 pages and was written by Steve Moore and drawn by the incomparable John Bolton, whose mastery of lights and darks wrings every drop of mood out of the meager horror moments found within.

It helps, of course, that Moore only had 15 pages to adapt a 93-minute movie; he cut all the scene-setting way, way down and really let Bolton run loose on the stuff we came to see: Oliver Reed as a werewolf. Thanks to the black-and-white artwork, it gives this Curse a more old-timey feel, something akin to the classic Universal horror movies of the 1930s and ’40s. The painted cover is quite beautiful, as well.

I hope I don’t sound too harsh on Curse, it’s a handsome movie with some fine performances, a few offbeat moments, and a finale that is exciting, bloody, and tragic—exactly the kind of stuff we go to horror movies for. But Hammer was generally not shy about showing their monsters, whether they be Draculas, Frankensteins or mummies. In The Curse of the Werewolf the minimalist approach is taken just a bit too far, with too many talky scenes before we get to see what’s so luridly promised on the poster.

Maybe if Hammer had given werewolves a second, er, shot, they might have realized this — and given us another werewolf movie that wasn’t so afraid to go for jugular.

—

Rob Kelly is a writer/artist/comics and film historian. He is the host or co-host of several shows on The Fire and Water Podcast Network, including Aquaman and Firestorm: The Fire and Water Podcast, The Film and Water Podcast, TreasuryCast, Superman Movie Minute, and Pod Dylan.

You can read more of Rob’s REEL RETRO CINEMA columns — including several on Hammer Films — here.

For more on The Curse of The Werewolf, check out the September 22, 2016 episode of Super Mates Podcast, part of The Fire and Water Podcast Network.

February 11, 2018

Man, I had never seen any of the Bolton adaptation. Fantastic stuff!

I have a soft spot for this movie, but I agree the pacing is a problem. I personally think we spend a bit too much time with Sinestro as well, but we definitely could have used more Werewolf. Such a great design. Universal distributing this movie made for some weird amalgamations of Leon and Larry Talbot’s Wolf Man in merchandising of the 60s. The Wolf Man was often depicted in a frilly shirt with waistband and an extra set of pointy ears on top of his head!