The Creeper was the opening line. The Hawk and Dove — introduced April 25, 1968 — was the exclamation point…

By PAUL KUPPERBERG

OK, it’s early 1968. Two years earlier, Steve Ditko (November 2, 1927 – June 29, 2018) had stunned the comics world when he quit Marvel Comics where he had done landmark work on his co-creations, Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. His famous final issue of the wallcrawler was The Amazing Spider-Man #38 (July 1966), which went on sale April 12, 1966. By all accounts, the rift in the creative approaches between Ditko and Stan Lee had grown too wide to be breached, so Steve took his boundless imagination and pencil and went elsewhere.

For a while, elsewhere was also Charlton Comics, that little company in Derby, Connecticut, that paid minimum wages, but which was in the middle of their own brief superhero renaissance, allowing Steve to return to Captain Atom and work anew on such characters as the Blue Beetle and the Question. Steve had done some of his earliest work for Charlton in the 1950s and must have felt right at home with the old gang. He also contributed 16 stories, most written by Archie Goodwin and produced in a lush ink-wash technique, to the Warren black-and-white horror magazines.

Remember: 1968. There’s no internet, and a small (if not dedicated) organized fandom, but for the regular (if not dedicated) reader like me, there’s no way to know what’s coming up in the comics except for what the publisher revealed in their fan pages and house ads. Today, we know six months or a year in advance of a big-name switching assignments and companies, but in 1968, an artist going from Marvel to DC was a Big Deal! Only a few years earlier, guys like Gene Colan and Mike Esposito were using pseudonyms to hide that they were working for the competition, and fans could no more imagine the Fantastic Four’s Jack Kirby and Spider-Man’s Steve Ditko at DC than they could Green Lantern’s Gil Kane or Wonder Woman’s Ross Andru at Marvel. And yet…!

But leave it to Ditko to make the impossible happen, because he took the leap from the House of Ideas to the Distinguished Competition, with that stop along the way with at Warren and Charlton — which brings us to Dick Giordano, the latter publisher’s longtime employee, artist and executive editor. 1968 was also the year DC hired Dick away from Charlton and he brought with him such creators as Denny O’Neil, Jim Aparo, Steve Skeates… and Steve Ditko.

The reason Dick and other artists like Joe Orlando, Joe Kubert and Mike Sekowsky were made editors to work alongside the long-established staffers like Julie Schwartz, Mort Weisinger and Murray Boltinoff was Carmine Infantino’s ascension to editorial director when DC Comics was sold to Kinney National Company. Carmine was hoping to shake up the status quo with new, younger editors and talent, as well as new and different titles. The years of 1968 and 1969 saw a lot of chances taken on new books like Secret Six, Bat Lash and the Ditko titles, most of which didn’t last beyond six issues.

Ditko’s DC debut was the Creeper in Showcase #73 (March/April 1968), which went on sale in late January of 1968. Ditko is credited with the story and art, with dialogue by Don Segall, and DC stalwart Murray Boltinoff is the editor. This is Ditko unleashed… at least as unleashed as he got in a Code-approved, mainstream comic. But the philosophic tropes that he had introduced in his Charlton heroes, particularly the Question, were expressed now by Jack Ryder and company, the theme of good vs. evil, of societal behaviors being matters of black or white. But beneath the veneer of politics, the Creeper was a pretty standard superhero comic book.

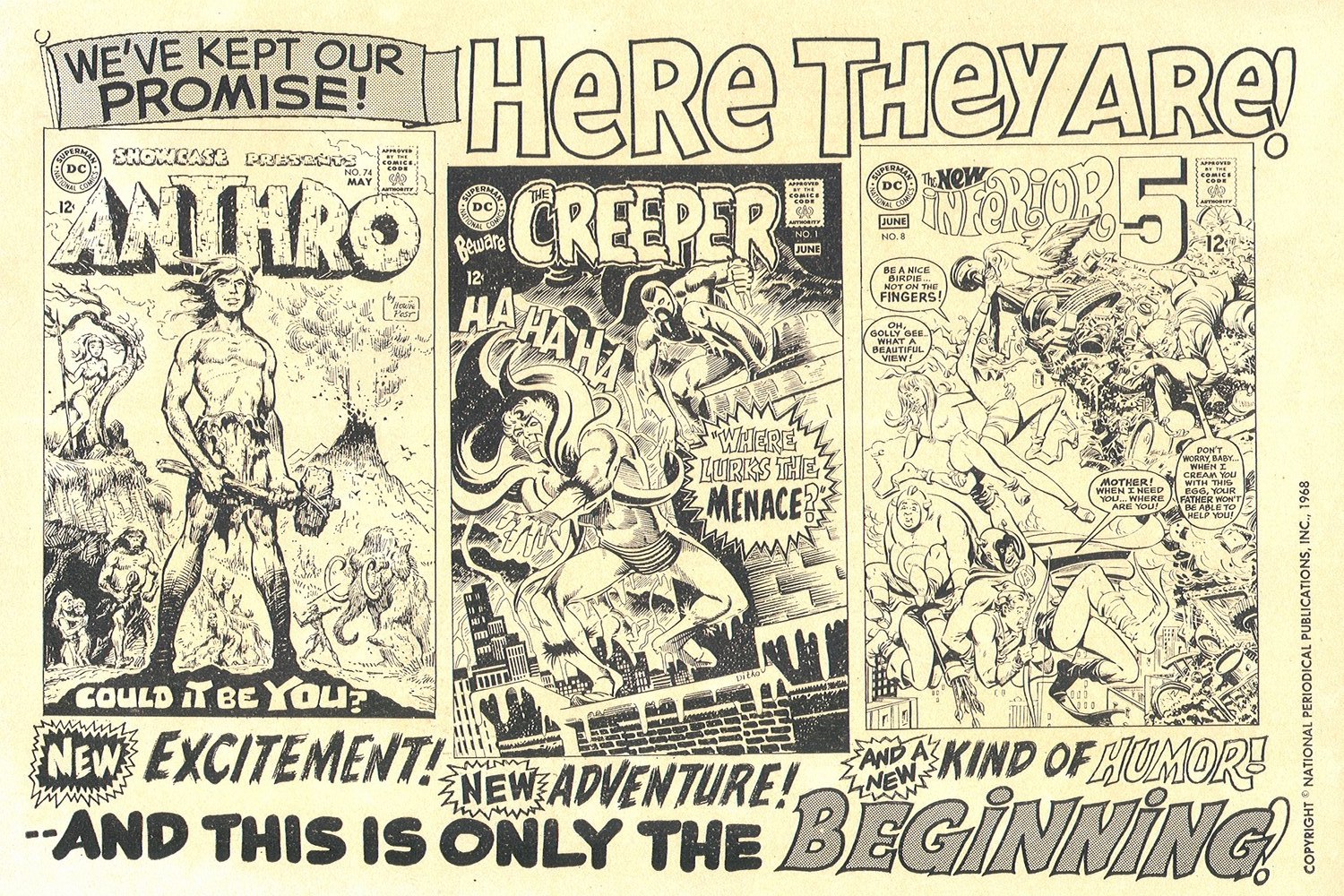

The first issue of the Creeper’s own title was already in the works by his Showcase appearance; an ad for Beware the Creeper #1 appeared in Showcase #74 (featuring Howie Post’s charming Anthro) and Showcase #73 ended with a half-page house ad blasting out: “Steve Ditko… Like Lightning… Strikes Again! The Hawk and the Dove, Coming Soon!”

The Hawk and the Dove was, in fact, a highly charged concept for a comic book in 1968. It addresses the Vietnam War and the protest movement against it, without, of course, getting specific. It is a very political comic book, though when I first read it as a 12-year-old the politics went over my head, but I certainly related to brothers Hank and Don Hall who couldn’t agree on anything. That was right up my alley. The only thing that kept (Skeates’) message of peace from being subversive to the political (and probably company’s) status quo was (Ditko’s) equally strong argument in support of war.

The series’ genesis is vague, but all involved seemed to have agreed it was the result of some combination of ideas and suggestions from Ditko, Infantino, Skeates and Giordano. Whatever the mix, the tenor of the series was pure Steve Ditko. Black vs. white. Good vs. evil. Reason vs. emotion. Page one begins with a bang as younger brother, high schooler Hank leads a counter-demonstration against college student Don’s anti-war protest on the college campus. There are placards aplenty on both sides, proclaiming in identical, unadorned lettering their contrary positions, probably copied straight from Political Protest Signs for Dummies: “Keep up the bombing” and “Stop the bombing.”

Which is about the level of debate throughout the story: Hank is a hawk who believes there are times when only violence will get the job done. Don is a dove who believes there’s always a middle ground and compromise. Their father, Judge Hall, thinks they’re both wrong: “The only way to solve problems is though logic!” Which is all well and good until the henchmen of the crook the good judge just put away tosses a bomb into the Hall home to blow the self-righteous old fart to hell.

The judge survives and is hospitalized. Even though he’s under police guard, his sons fear for his safety, and rightly so as, the next day, Hank spots the man who threw the bomb at their father lurking outside the hospital. Interestingly, this bomber, the personification of evil in the story, is never given a name. He’s only ever referred to as “Boss” by his gang, and only one of those three throwaway characters is named, “Max,” and only in one panel. It’s as though they’re not fleshed out characters, merely avatars representing symbols of evil.

Hank wants to jump the guy. Don wants to call the police. They compromise by following him, and he leads them to the bad guys’ hideout in (where else?) an old, abandoned warehouse. Hank is cocksure aggression, charging headlong into situations in his belief that action is the only answer. Don’s pacifism is wishy-washy, a follower never willing to push very hard for his own ideas.

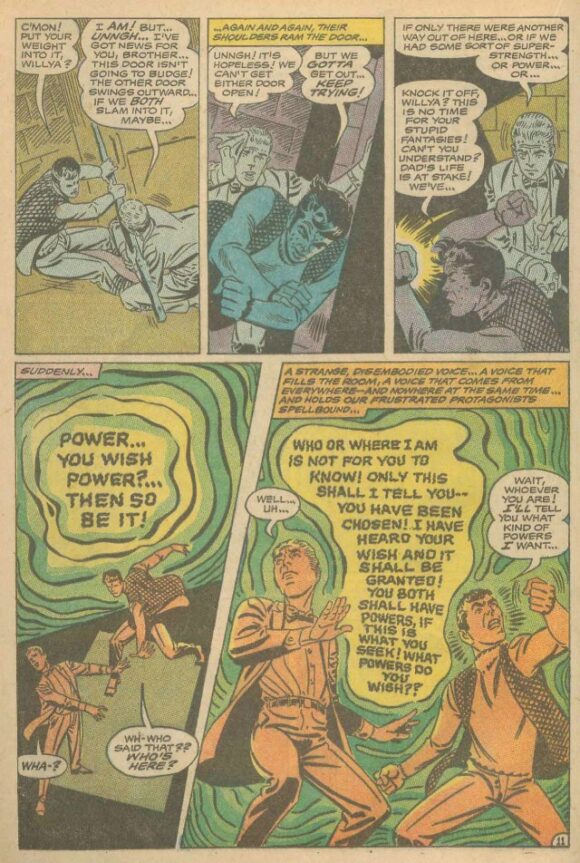

The boys get accidentally locked in a dark, dank room, where they overhear the thugs leaving for the hospital, where the Boss has bribed an orderly to get them into the judge’s room so they can kill him. But try as they might, they can’t escape their locked room, though that doesn’t stop the intrepid Hank from pounding at the door while Don indulges in one of his “stupid fantasies,” wishing for another way out, “or if we had some sort of super-strength… or power….”

They don’t have powers, but because this is a comic book, they soon will, courtesy of a “strange, disembodied voice” that fills the room. I guess the situation being what it was, neither boy was very startled for very long, and Hank immediately wishes for “the power to break out of here… the power to stop the creeps who are after dad… the power to smash them… tear them apart so they’ll never commit crimes again!”

Don, on the other hand, wants “to save father, not smash criminals, let the police handle them!” He doesn’t want to resort to “meaningless violence,” but the Voice has had enough of their brotherly bickering and silences them, declaring, “We seem to have here a hawk and a dove! So be it! Let the transformation begin!”

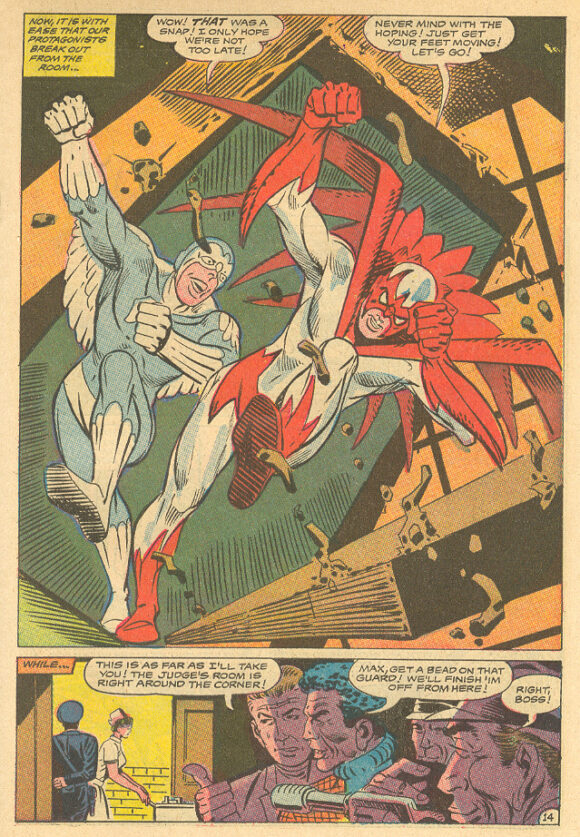

And quicker than you can say “secret origin,” Hawk and Dove are born, and wasting no time except for a page and a half of exposition, the brothers smash through the door and race to the hospital, leaping over cars and pedestrians and swimming a river to get there. The new heroes arrive just in the nick of time… well, for dad anyway; his police guard takes a bullet just before their arrival, poor bastard.

Hawk takes to beating on thugs like a fish to water: “You won’t get any mercy from me! I’m gonna play this game the same way you’re playin’ it!” And, as a caption tells us, “Meanwhile, the Dove fights with restraint,” but what he’s doing isn’t fighting, it’s trying to talk the bad guys into giving up: “If we don’t stop you, the law will catch up with you in the end anyway!” That gets him shoved out the window.

Fortunately, he saves himself by grabbing onto a flagpole outside the window, climbs back inside, and is proud of how he’s able to duck and weave past the thugs without having “to resort to violence” and bat aside the Boss’ gun before he can pull the trigger. In the end, it takes Dove’s passivity and Hawk’s violence to save the day, although Dove holds onto his belief until the end: “You didn’t hafta do that! I coulda held him!”

Expecting thanks from Judge Hall for their efforts, the boys, reverted to normal once the action has ended, arrive back at their father’s room in time to hear the old man lambast his rescuers. Though appreciative of what they did, he tells reporters, “I cannot condone their actions! In this day and age, there can be no place for vigilante tactics…. I suggest that the two who call themselves the Hawk and the Dove turn themselves over to the authorities!”

As far as pacifist Don is concerned, “That does it! I never wanted to get into this crime-fighting bag, anyway!… Who needs it?” But aggressive Hank isn’t so easily deterred: “Dad’s been a judge so long he’s beginning to think like a law book! With their abilities, the Hawk and Dove could do a lot of good! Why can’t dad see that? It’s so obvious to me! You know that!”

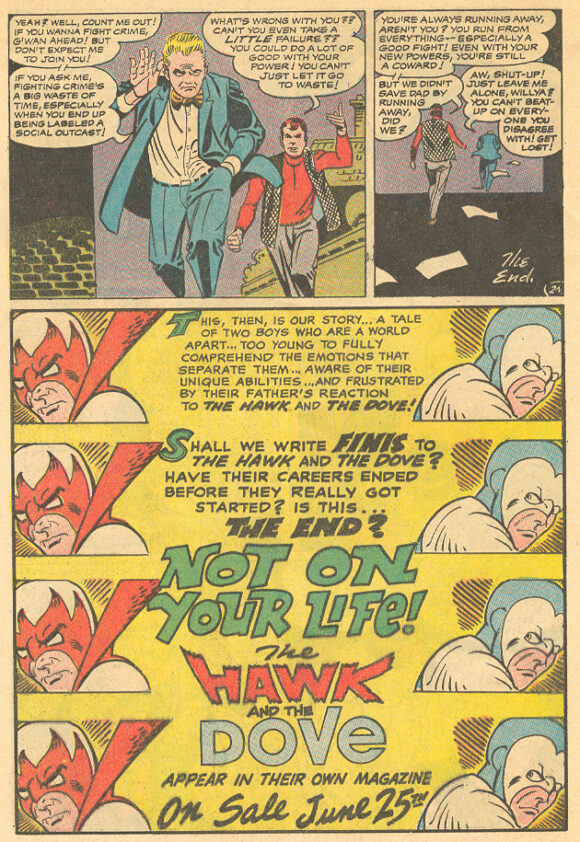

“Yeah? Well count me out!” Don insists. “You can’t beat-up on everyone you disagree with! Get lost!”

“The end.”

But this wasn’t the end. In fact, it was just the beginning of the debate for Hank and Don Hall, although Steve Ditko would only stick around for the first two of the six issues of the bi-monthly The Hawk and the Dove title. Steve Skeates was gone after #4, both replaced by Gil Kane who, needless to say, did not share the politics of either of the Steves who preceded him. According to Wikipedia, “the reasons for his departure [are] uncertain,” but knowing what we do of Ditko’s rigid moral code, it’s hardly surprising. My take on it is that someone at DC made Steve a promise that they didn’t keep.

There was never anything subtle about Ditko’s storytelling. He was a message writer to whom characterization and plot were subservient to his Objectivism philosophy, subjects he would expand upon in his later, self-published work, like The Avenging World, The Avenging Mind and his Mr. A stories. And, while scripter Steve Skeates was capable of writing fully formed and fleshed out characters, the final product was shaped by Ditko. “In penciling it up Steve took out scenes he didn’t like and extended scenes he did like. Then, I added dialogue and captions to these new extensions,” Skeates said in an interview in Comic Book Artist #5.

So, yeah. Steve Ditko at DC. It was huge, even if it was for so short a period. But he would be back!

—

MORE

— WORKING WITH DITKO: An Illustrated Memoir by JACK C. HARRIS Is Coming This Fall. Click here.

— The TOP 13 STEVE DITKO SPIDER-MAN Covers — RANKED. Click here.

—

PAUL KUPPERBERG was a Silver Age fan who grew up to become a Bronze Age comic book creator, writer of Superman, the Doom Patrol, and Green Lantern, creator of Arion Lord of Atlantis, Checkmate, and Takion, and slayer of Aquababy, Archie, and Vigilante. He is the Harvey and Eisner Award nominated writer of Archie Comics’ Life with Archie, and his YA novel Kevin was nominated for a GLAAD media award and won a Scribe Award from the IAMTW. Now, as a Post-Modern Age gray eminence, Paul spends a lot of time looking back in his columns for 13th Dimension and in books such as Direct Conversations: Talks with Fellow DC Comics Bronze Age Creators and Direct Comments: Comic Book Creators in Their own Words, available, along with a whole bunch of other books he’s written, by clicking the links below.

Website: https://www.paulkupperberg.net/

Shop: https://www.paulkupperberg.net/shop-1

April 25, 2023

It’s too bad Steve didn’t stay a lot longer on his Marvel and DC books. They are among my favorite comics!

April 25, 2023

I used to believe that Ditko’s politics clashing with O’Neil, Skeates & Giordano led him to quit the Creeper and Hawk & Dave, but apparently it was his health. Ditko had contracted tuberculosis in the 1950s, and according to his obit in the Comics Journal, he suffered a relapse in 1968 forcing him to withdraw from the series he created.

April 26, 2023

Paul,

A nice look back at Ditko’s work for DC in 1968. I’d offer one correction, though. Giordano didn’t bring Ditko to DC, It was the other way around, Giordano noted in his interview in Comic Book Artist # 1, 1998: “…Steve Ditko came up and told me the people at DC were interested in talking to me about taking an editorial position. He was really the catalyst for that move.”

After Ditko left Marvel he freelanced all over. In addition to Charlton and Warren, he worked with Wally Wood at Tower and drew a few stories for ACG and Dell. Ditko likely sought out work at DC on his own, In personal correspondence (which appeared in my Ditko Bio in Alter Ego # 160) he explained: “..DC comics editors rejected me until Carmine Infantino took over.” As you noted Ditko’s first editor on the Showcase issue of The Creeper was Murray Boltinoff. Ditko was then paired with Giordano when he came over to DC.

Ditko left both strips when he fell ill (as noted in The Comic Reader) with the last issue of the Creeper completed by Jack Sparling.

January 29, 2024

I’ve noticed Ditko’s and Jack Kirby’s work at Marvel in the 60s had a more polished look than some (though not necessarily all) of their later work. And I don’t mean to undermine either’s contributions to the Marvel Age. I have found some of Kirby’s best art for the Fantastic Four to have been inked by Joe Sinnott. Was there a particular inker for much of Ditko’s Spider-Man and Doctor Strange stories?