SCOTT SHAW! SATURDAYS…

By SCOTT SHAW!

From the 1930s through the 1950s, there were very few Black comic book characters other than goofy sidekicks or fiendish tribesmen. For that matter, there were few comic book writers or artists who were Black, either.

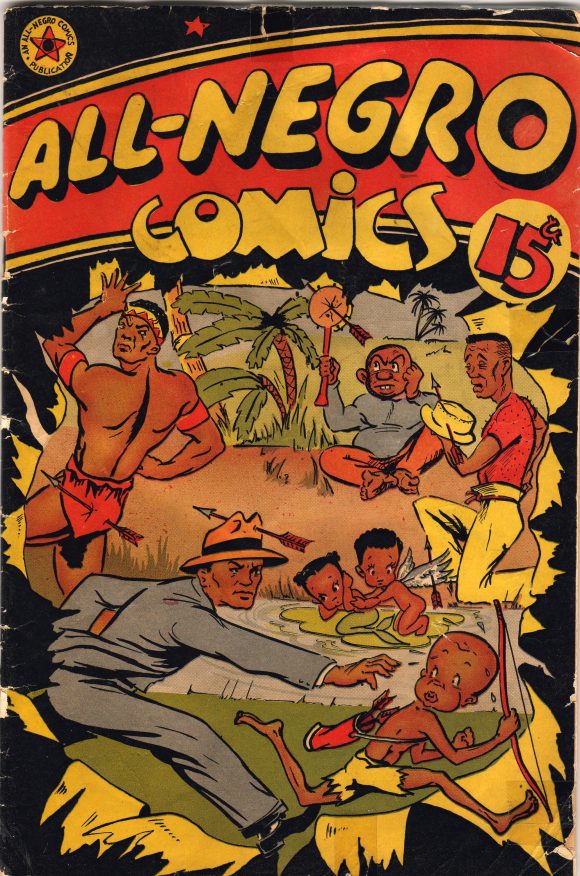

The first example of a comic book that was published for a Black readership was 1947’s All-Negro Comics #1, with a publisher, editor, writers, and artists who were all African-American. Unfortunately, none of this unintended one-shot’s characters were particularly memorable, and its 15-cent price seemed outrageous at the time. Further, too many white American readers weren’t ready for a comic that eschewed Black stereotypes. (A special edition will be released this fall by Image.)

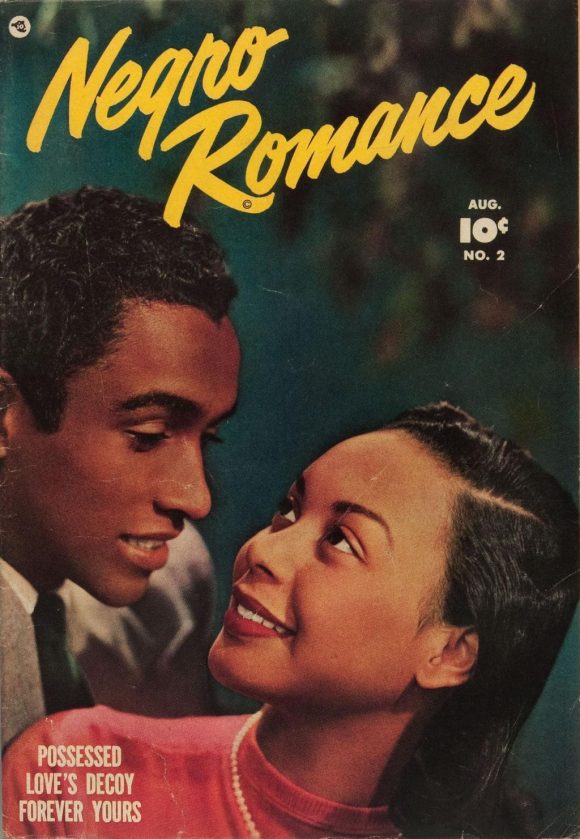

It was, however, a beginning. A few years later, there was Negro Romance, a four-issue series that started in 1950 at Fawcett, with a final issue from Charlton five years later.

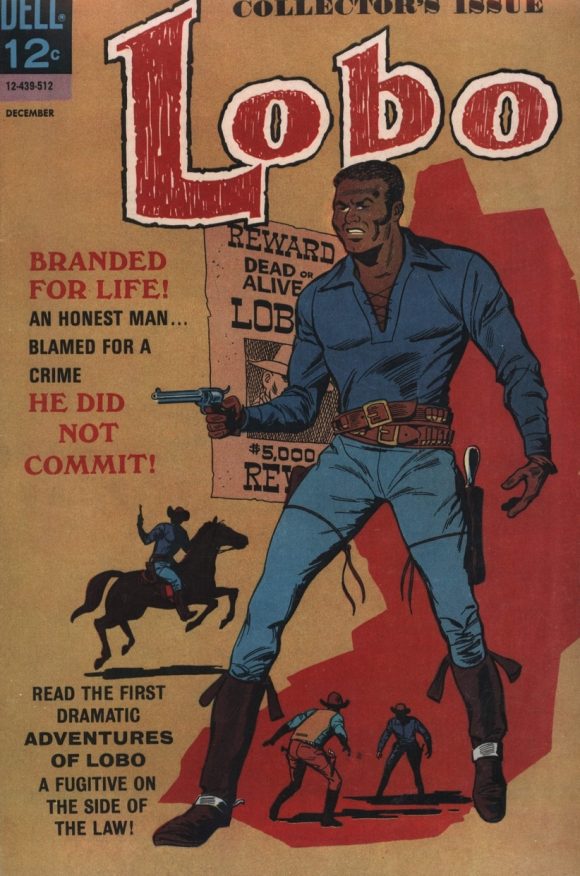

Finally, in the mid-’60s, things began to change. In 1966, Fantastic Four #52 introduced comicdom’s first black superhero, the Black Panther, created by Jack Kirby, based on his “Coal Tiger” character. Later that same year, Dell’s Lobo first appeared. Although there were only two issues published, Lobo, a former slave in the Old West, was the first Black character with his own series.

All of this eventually led to Fast Willie Jackson, who’s often referred to as “the black Archie,” created by Bertram Fitzgerald Jr.

Born in Harlem in 1932, Fitzgerald was an avid reader, devouring books and novels — works of history and adventure. But he was frustrated by the stereotypical and offensive depictions of Black people, or the absence of Black characters all together.

“It’s every bit as important for white children to learn about Benjamin Banneker as it is for Black children to learn about Benjamin Franklin,” Fitzgerald told The New York Times. “It encourages (whites) to think that they made every worthwhile contribution to society, and it misleads them to believe that they are somehow superior.”

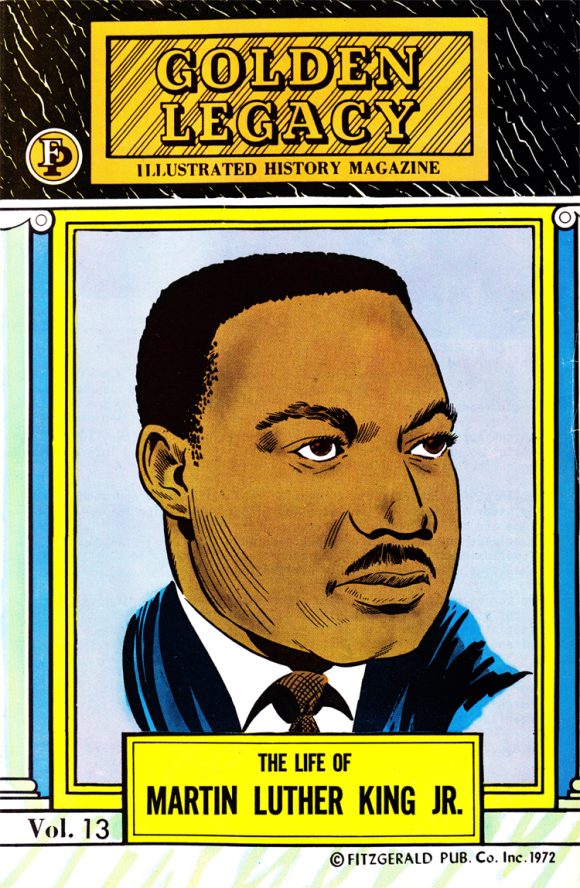

In 1966, although he wasn’t a comic book fan, Fitzgerald realized their literary impact and published Golden Legacy, inspired by Gilberton’s Classics Illustrated. It was a 16-issue series of biographies of notable figures in Black history, from Harriet Tubman, to Alexandre Dumas, to Joseph Cinqué, and many more.

“We decided on the format because, first of all, it appeals to youngsters aged 10 through 15, when lifelong attitudes are being formed,” he explained in the interview. “Secondly, the visual approach has more impact on the reader. Lastly, it takes the drudgery out of history and replaces it with excitement and adventure. It sort of puts a breath of life into it.”

With a shoestring budget and other limitations, Fitzgerald approached Coca-Cola, which had a strong Black market. Coke agreed to sponsor the series — and was later joined by other major companies, such as AT&T, Columbia Pictures, Exxon and McDonald’s, as it became more popular and lauded by educators. From 1966 to 1976, the series sold 25 million copies.

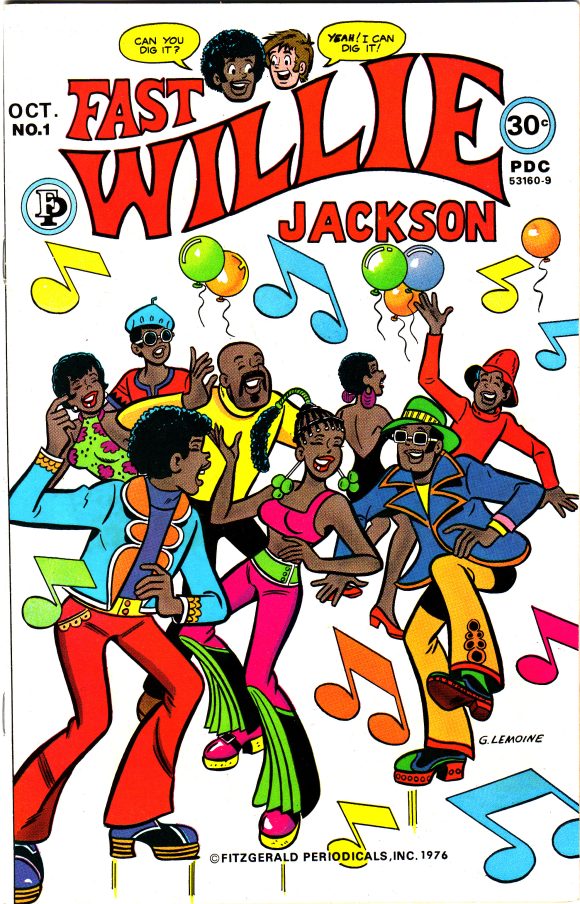

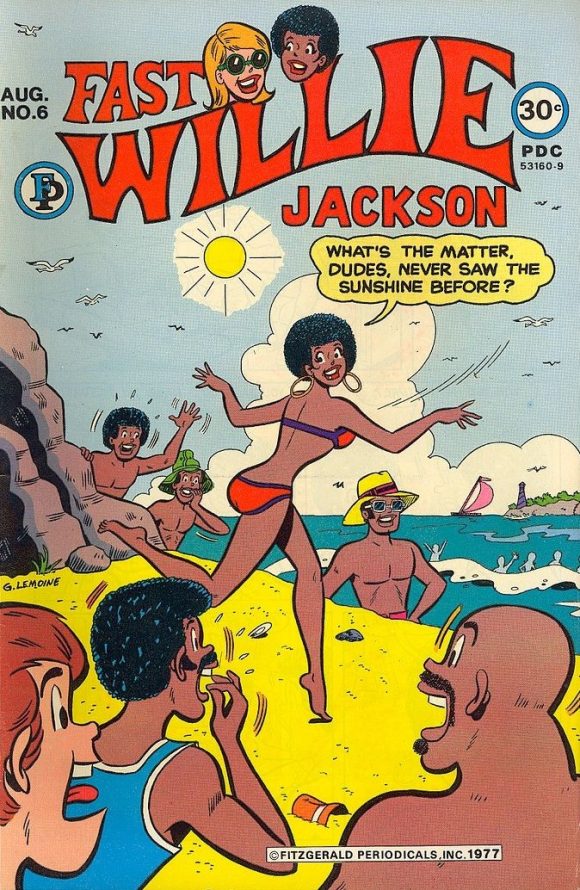

Following Golden Legacy, Bertram introduced a second comic book series that was full of Black characters, but with a strong vibe of Archie Comics: Fast Willie Jackson (October 1976 to September 1977) was created to fill a perceived need, serving a demographic that had been under-represented in American comic books. (At that time, Archie’s comics featured very few characters that were not Caucasian.) Fast Willie Jackson followed Archie’s path of short strips focused on friends and hi-jinx, but with a deeper political lean.

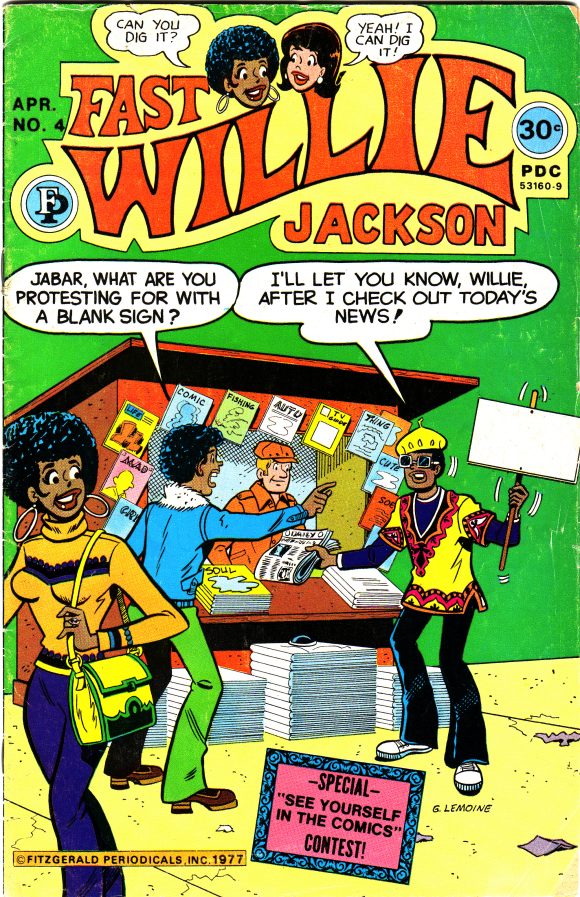

Fast Willie was a lot like Archie Andrews — well-liked, fun, and able to talk his way out of minor problems. Like Veronica Lodge, slightly snobbish Dee Dee was obsessed with fashion. Jo-Jo was a ripoff of Jimmie Walker’s J.J. Evans on Good Times, with a bit of Jughead Jones added in. “Right On” Jabar was a “power to the people” militant. Hannibal was a strongman but without the potential threat of ever-jealous Moose Mason. Frankie Johnson was a wealthy kid with a tinge of superiority, a la Reggie Mantle.

The kids were friendly with Puerto Rican José Martinez, who ran “The Spanish Main,” the local teen hangout, and an Asian owner of a local martial arts school. The only white regulars were Officer Flag aka “The Man,” a friendly but dimwitted policeman, and the nameless Caucasian above the cover’s logo, who’s responding to Fast Willie’s question, “Can you dig it?”

The primary writer for Fast Willie Jackson was Fitzgerald himself, but he wasn’t adept at teenage humor. Contemporary commentators have remarked that he should have hired someone else, because the scripts tended to be flat and unfunny.

Most of Fast Willie Jackson’s stories were drawn by “Gus Lemoine,” a name that pops up a lot on the Grand Comics Database. It’s now obvious that “Gus Lemoine” was Archie Comics’ Henry Scarpelli, whose other work included DC’s Swing With Scooter, Charlton’s Abbott & Costello, Dell’s The Beverly Hillbillies, and Marvel’s Millie the Model.

Unfortunately, Fast Willie Jackson‘s distribution wasn’t good, so many readers never encountered the comic. The series only lasted seven issues and they were the last comic books published by Fitzgerald Periodicals. They’re now highly collectable.

Still, back when Fast Willie Jackson was available on newsstands, it was important to give young readers of color an opportunity to see characters who looked like them, just as it is today. The series’ legacy remains a notable subject in the history of comics, Oddball and otherwise.

—

Want more ODDBALL COMICS? Come back next week!

—

MORE

— ODDBALL COMICS: Jack Mendelsohn’s Wonderfully Loopy JACKY’S DIARY. Click here.

— ODDBALL COMICS: Psychedelic and Surreal Stuff — For Kids! Click here.

—

For over half a century, SCOTT SHAW! has been a pro cartoonist/writer/designer of comic books, animation, advertising and toys. He is also a historian of all forms of cartooning. Scott has worked on many underground comix and mainstream comic books, including Simpsons Comics (Bongo); Weird Tales of the Ramones (Rhino); and his co-creation with Roy Thomas, Captain Carrot and his Amazing Zoo Crew! (DC). Scott also worked on numerous animated series, including producing/directing John Candy’s Camp Candy (NBC/DIC/Saban) and Martin Short’s The Completely Mental Misadventures of Ed Grimley. As senior art director for the Ogilvy & Mather advertising agency, Scott worked on dozens of commercials for Post Pebbles cereals with the Flintstones. He also designed a line of Hanna-Barbera action figures for McFarlane Toys. Scott was one of the comics fans who organized the first San Diego Comic-Con.

Need funny cartoons for any and all media? Scott does commissions! Email him at shawcartoons@gmail.com.

September 20, 2025

I actually did see this on the racks back in the day, but White Boy me mainly interested in superheroes didn’t even give it more than a passing glance.

September 21, 2025

There was some comics exhibit here in NYC that had a couple of these under glass as part of the presentation, but I’ve never seen or heard of Fast Willie Jackson before. Very cool article, thanks for sharing.

September 23, 2025

Thanks, Scott. Reading about these comics is both entertaining and educational, which after all was the original goal of Bertram Fitzgerald’s work. Erik Larsen – like you, an astute comic historian as well as an artist – brought Fast Willie back for a fun cameo in his Savage Dragon comic some years ago. Tom Brevoort has also written about the series. So it hasn’t;t been entirely forgotten. It would be great to have the series reprinted for a modern audience – Lobo, too!