“We must not roast anybody alive”: An 11-point plan to keep things squeaky clean — years before Wertham…

The story goes something like this: Comic-book publishers freely reveled in the grotesque and disgusting for years before shrink-cum-charlatan Dr. Fredric Wertham ginned up enough outrage in the early ’50s to force the creation of the Comics Code Authority.

That’s more or less true but it is a gross oversimplification of what happened as the Golden Age of Comics faded into oblivion.

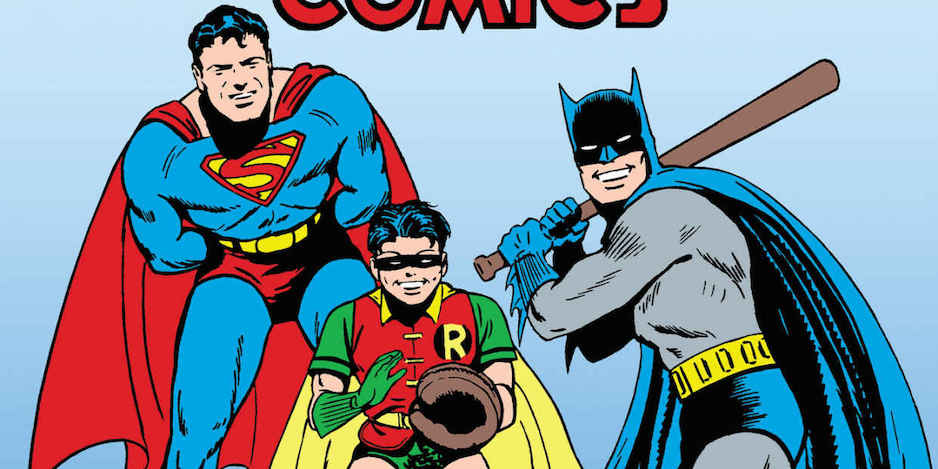

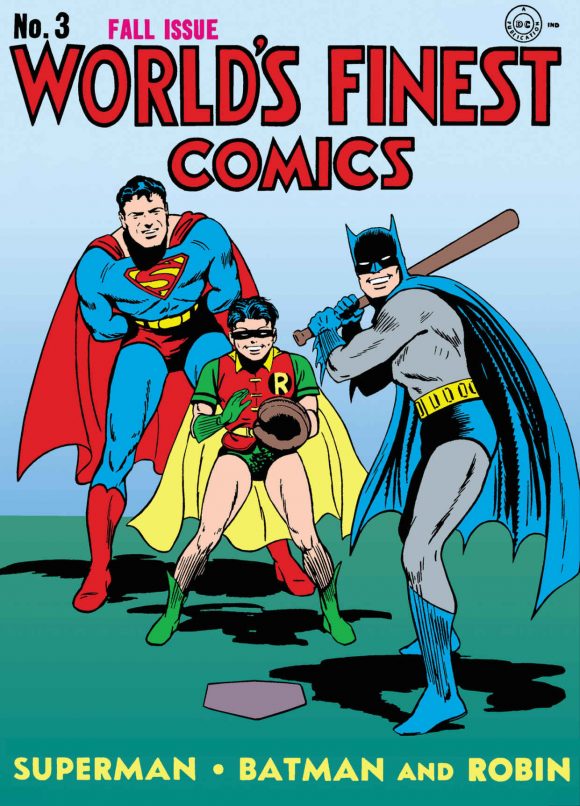

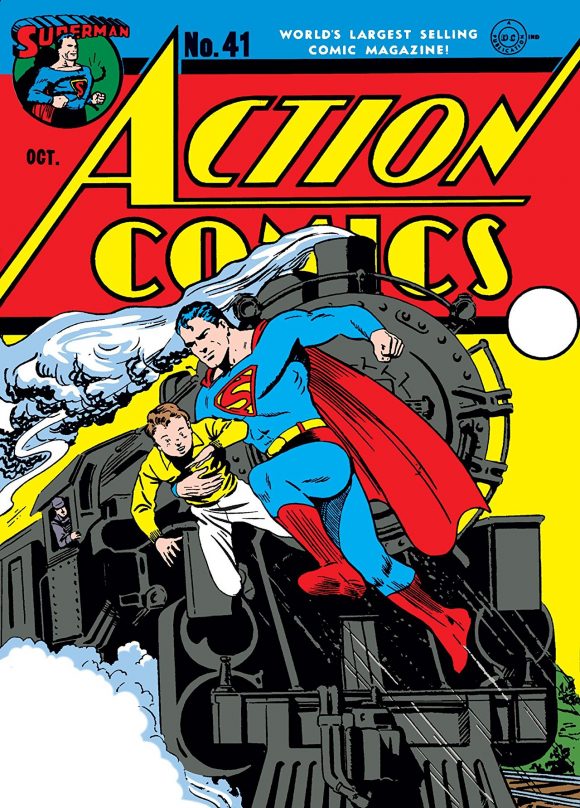

As it happens, the pressure on the industry to rein itself in began much earlier — not long after comic books exploded in popularity with Superman’s 1938 debut in Action Comics #1 – and you can get some insight into how it played out in TwoMorrows’ American Comic Book Chronicles, The 1940s: 1940-44, which is due out July 31 (click here).

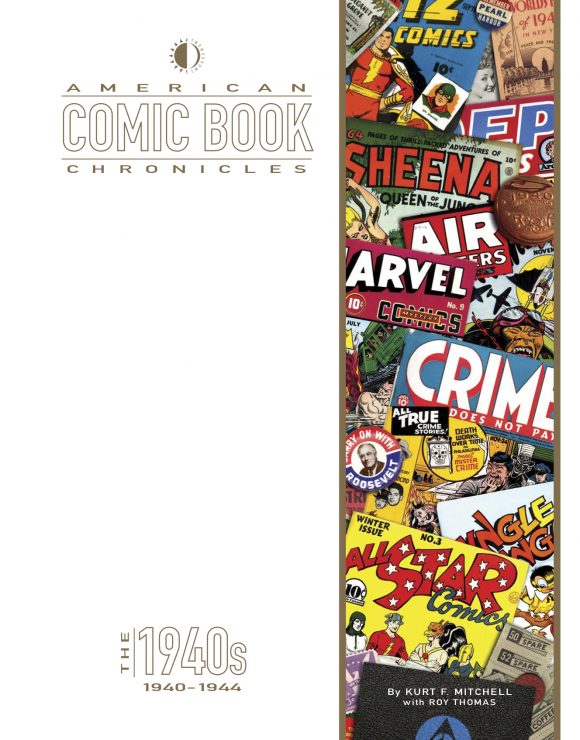

The book — written by Kurt F. Mitchell, with comics luminary Roy Thomas, who edits TwoMorrows’ Alter Ego magazine — is the latest in the American Comic Book Chronicles series and covers a broad range of topics.

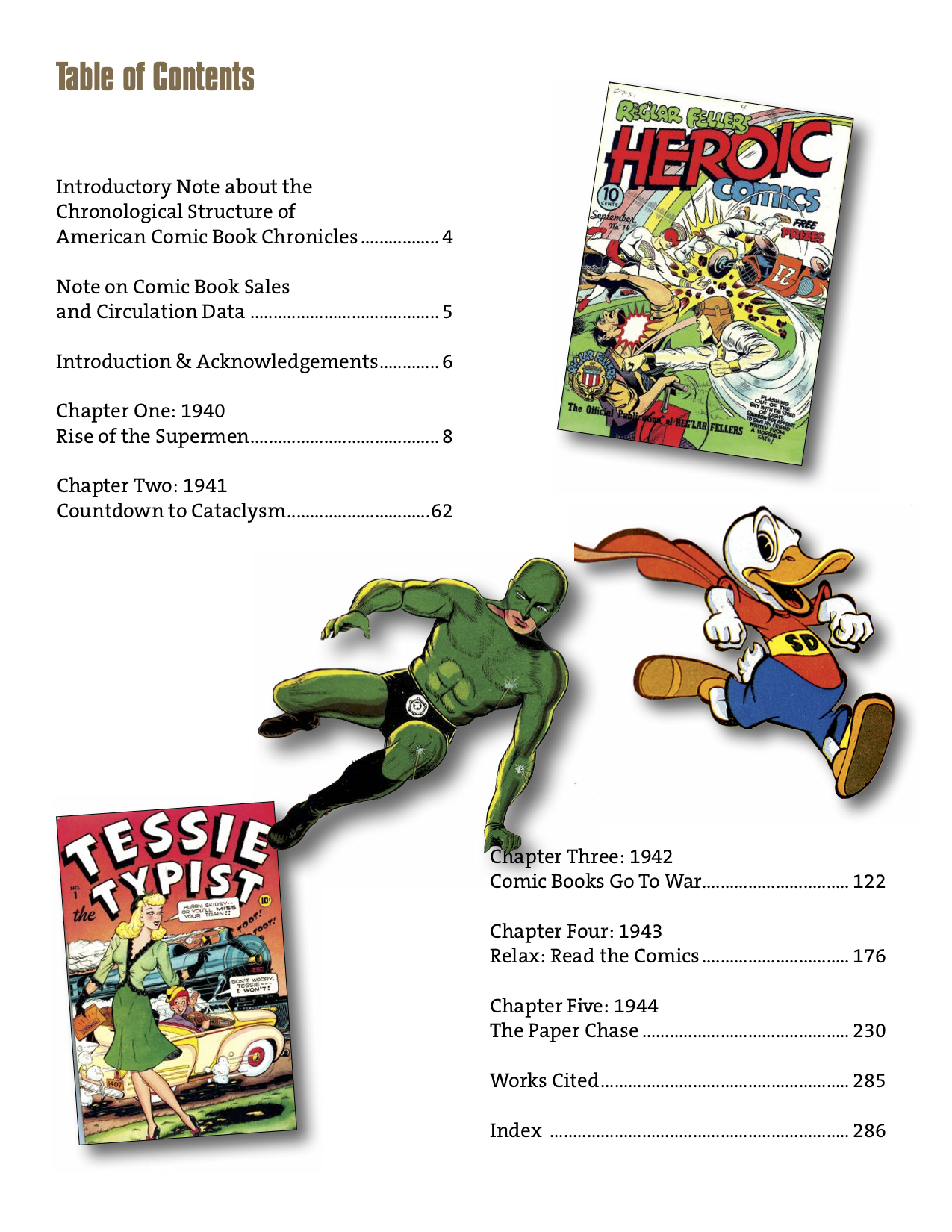

Just check out the table of contents:

But what caught my eye for this EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT was a section in the 1941 chapter where the authors lay out what the leadership of DC Comics (and its sister company All-American) did to keep critics at bay — adopt an 11-point code that, in the hindsight of nearly 80 years, is simultaneously hilarious and not funny at all:

—

By KURT F. MITCHELL, with ROY THOMAS

As Harry Donenfeld traveled the country basking in the success of his comic book empire, the ever-practical Jack Liebowitz took steps to ensure their company would not fall prey to the public vilification and judicial censorship that befell the publishers’ “spicy” pulp line years before. Stung by (writer and literary critic) Sterling North’s denunciation of the industry, Liebowitz cast about for an effective counterargument. He found it in the pages of the July 1941 issue of The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, in an article co-authored by Dr. Lauretta Bender, a widely respected child psychiatrist affiliated with New York’s famed Bellevue Hospital:

“Comic books can probably best be understood if they are looked upon as an expression of the folklore of the age[, comparable to] the mythology, fairy tales and puppet shows, for example, of past ages. … All of these are what we might call an outgrowth of the social unconscious; the social problems of the time are expressed through them. Many of them have so well stated the fundamental human problems that they have remained vital throughout the ages and are the literature of choice for children… Since our enemies are no longer animals, and man-to-man combat is much less, [these men- aces are] replaced by the problems of science, mass organization and social ideologies. … The magic in the comics is therefore expressed in terms of fantastic elaborations of science[, a] greater magic needed in modern folklore … due to the greater dangers which assail society and the individual. …

“[N]ormal, well-adjusted children with active minds, given insufficient outlets or in whom natural drives for adventure are curbed, will demand satisfaction in the form of some excitement. Their desire for blood and thunder is a desire to solve the problems of the threats of blood and thunder against themselves or those they love, as well as the problem of their own impulses to retaliate and punish in like form. The comics may be said to offer the same kind of mental catharsis that Aristotle claimed was an attribute of the drama. … The chief conflict over comic books is in the adult’s mind.”

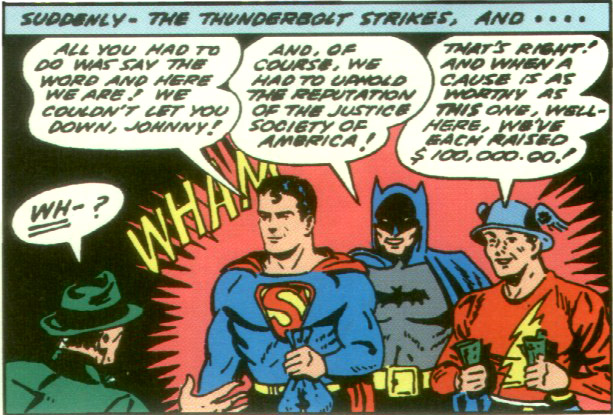

It was exactly what Liebowitz wanted to hear. Not only were his comics in the grand tradition of children’s literature, they were actually good for kids! He contacted Dr. Bender and offered her a seat on his new Editorial Advisory Board. Her colleagues included Dr. Robert Thorndike of Columbia University’s Teachers College, child psychologist Dr. Ruth Eastwood Perl, New York University mythologist and folklorist Dr. C. Bowie Millican, boxing champ and Boy Scouts of America executive Gene Tunney, and Josette Frank of the Child Study Association of America, whose monthly column “Good Books for Reading” became a regular feature of the Detective and All-American lines. It was an impressive assembly of serious people.

An announcement in the October 1941 issues of every DC and AA title introduced the Advisory Board and explained its purpose:

“Since the inception of this and other DC magazines, a rigid policy has guided the editors in their selection and presentation of editorial material. A deep respect for our obligation to the young people of America and their parents and our responsibilities as parents ourselves combine to set our standards of wholesome entertainment. Early this year we recognized the value of active assistance on the part of those professional men and women who have made a life work of child psychology, education and welfare. As a result we secured the cooperation of [our] Advisory Editors, each a leader in his or her respective field.”

Writers and artists soon began receiving laundry lists of “thou shalt nots,” story elements the Advisory Board deemed no longer welcome in the pages of DC’s comic books. (It was likely their influence that drove changes to the Spectre and Doctor Fate.)

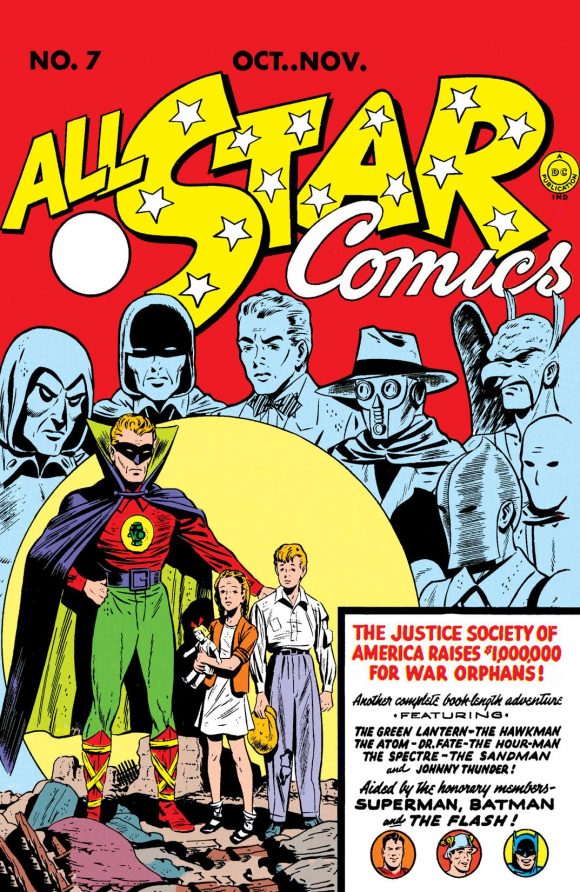

All-Star Comics #7

An undated memo from editor Sheldon Mayer to his staff, preserved in the papers of writer Gardner Fox, provides one such checklist of no-nos, some a direct response to Sterling North:

1. Under no circumstances are we to show a hypodermic needle. If it is necessary to drug a man, it can be done by use of a ray, or something equally fantastic.

2. We must never show a coffin, least of all with a corpse in it.

3. Never show an electric chair or a hanging. If we must show a hanging, a silhouette will do the trick. If we must show an electrocution, show other prisoners talking about it, then have the lights dim, and go on again. This is much more dramatic and will not offend the mothers and fathers of our readers.

4. We must never show anybody stabbed. If we should have a fencing scene, the ‘kill’ can be shown again in silhouette.

5. No blood or bloody daggers.

6. No skeletons or skulls.

7. We must not roast anybody alive.

8. No character is permitted to say, ‘What the…?’

9. No one is to be called ‘jerk’ …

10. Little children are not to be killed or to die of sickness, accident, etc., in the course of the story. It is all right for them to have died sometime before the story opens, and on rare occasions – not too often – it may be necessary to threaten their lives, but that’s all.

11. We must not chop limbs off characters – unless a character has been injured in a normal accident and had a limb removed by surgery. The same goes for putting people’s eyes out, etc., etc.

At the bottom of this memo, Mayer added a handwritten note: “P.S – Now go ahead and write a good story – I dare you. SM”

Through such guidelines, Donenfeld, Liebowitz, and AA co-owner M.C. Gaines sought to redefine themselves within the industry. Let Timely pit its heroes against ghouls and zombies and skull-faced Nazis. Any resulting outrage was no longer their problem.

The DC slug was now a guarantor of family-friendly entertainment.

—

The American Comic Book Chronicles, The 1940s: 1940-44 will be available July 31. You can get it in comics shops, at online retailers, or directly through TwoMorrows. (Click here for more info.)

—

MORE

— COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES: THE 1980s: A Look at Levitz and Giffen’s LEGION. Click here.

— 13 SUPER WEIRD HEROES of the Golden Age. Click here.

—

NOTE: The original piece included footnotes that can be found in the book itself.

July 20, 2019

But of course. There was simply too much money at stake. DC had struck the motherlode with Superman in Action Comics, and they quickly spun him off into a one-shot of his own — which sold so well that it immediately changed to an ongoing series. Then the syndicated newspaper strip, then the radio serial, then the Paramount cartoons. Superman was like DC having a license to print its own money. Then Batman, and then Wonder Woman. Compared to those, suddenly the once lucrative-seeming Spicy pulps looked like a nickle-and-dime operation. (Well, so were the comics, but there were a LOT more dimes involved this time.)

Any whiff of a backlash of parents and authority figures seeking to defame comics threatened to put an end to all that with negative publicity, so immediate affirmative action to combat that menace was a top priority for DC. Anything that could knock out the foundation of Superman comics from underneath would also topple the gigantic pile of cash licensing to other media built on top of it. Fawcett quickly followed suit when Captain Marvel and Spy Smasher were licensed to Republic Pictures for film serials, as did some of the other larger publishers.

You’d think that the immediate and somewhat overboard prohibitions would have tainted DC comics and turned off the young readers, but apparently once hooked, the comic habit was hard to quit. By the post-War years, a slightly older median-age reader would require stronger stuff to dig into his pocket for those dimes, but harmless funny animals were there for little brothers and sisters.

July 20, 2019

DC really was different in the old days.

July 20, 2019

Philip Gipson…EVERYTHING was different in the old days. TV and movies have had similar changes. Married couples used to sleep in different beds, on TV shows at least, in the old days. Language wasn’t anywhere near as foul. And the violence was tamer and a LOT less bloody.

The question is whether or not these changes are better because they are more realistic or whether the changes in the various forms of media have changed society for the worse and added to the coarseness BY the media culture. We’ve become an overly sexualized, overly violent and have overly harsh language. YAY freedom to be horrible.

The media as a whole IS a change agent that influences both good and bad. Sadly those influences seem to be getting worse and I applaud DC for being ahead of the curve before the Wertham paranoia began. Those 11 “no-no’s”, while they appear absurd today are the direct opposite of what the people of that past would view how we’ve become a society of just yes-yes.