An INSIDE LOOK at Eisner’s vision of the five boroughs…

By PETER BOSCH

New York and its people have long been the subject of Broadway plays and motion pictures, and some the greatest in both fields of the early- to mid-1900s were set far away from the glamorous, swinging society locations. Many of the very best for showing the city and its five boroughs were set in tenements, in productions such as Dead End, Street Scene, Naked City, and West Side Story. They showed life as it was among the poorer New Yorkers of their respective times.

New York tenements, 1895

However, when it came to doing the same in comics, no one – absolutely, no one – did it better than Will Eisner (born March 6, 1917, in Brooklyn). For many years, he captured the city in The Spirit newspaper section (it was originally set in New York before he changed it to Central City), but he returned to glory beginning in the 1970s when he started writing and drawing a series of graphic novels, a number of which were set in and around a fictional tenement building in the Bronx at “55 Dropsie Avenue.” There were stories from the past and present, many based on Eisner’s own recollections of growing up in New York.

He described 55 Dropsie Avenue the following way: “(It) was typical of most tenements. Its tenants were varied. Some came and went. Many remained there for a life time… imprisoned by poverty or other factors. It was a sort of micro-village – and the world was Dropsie Avenue. Within its walls, great dramas were played out. There was no real privacy – no anonymity. One was either a participant or a member of the front-row audience. ‘Everybody knew about everybody.’ The following are based on life in these tenements during the 1930s… the dirty thirties! They are true stories. Only the telling and the portrayals have converted them to fiction.”

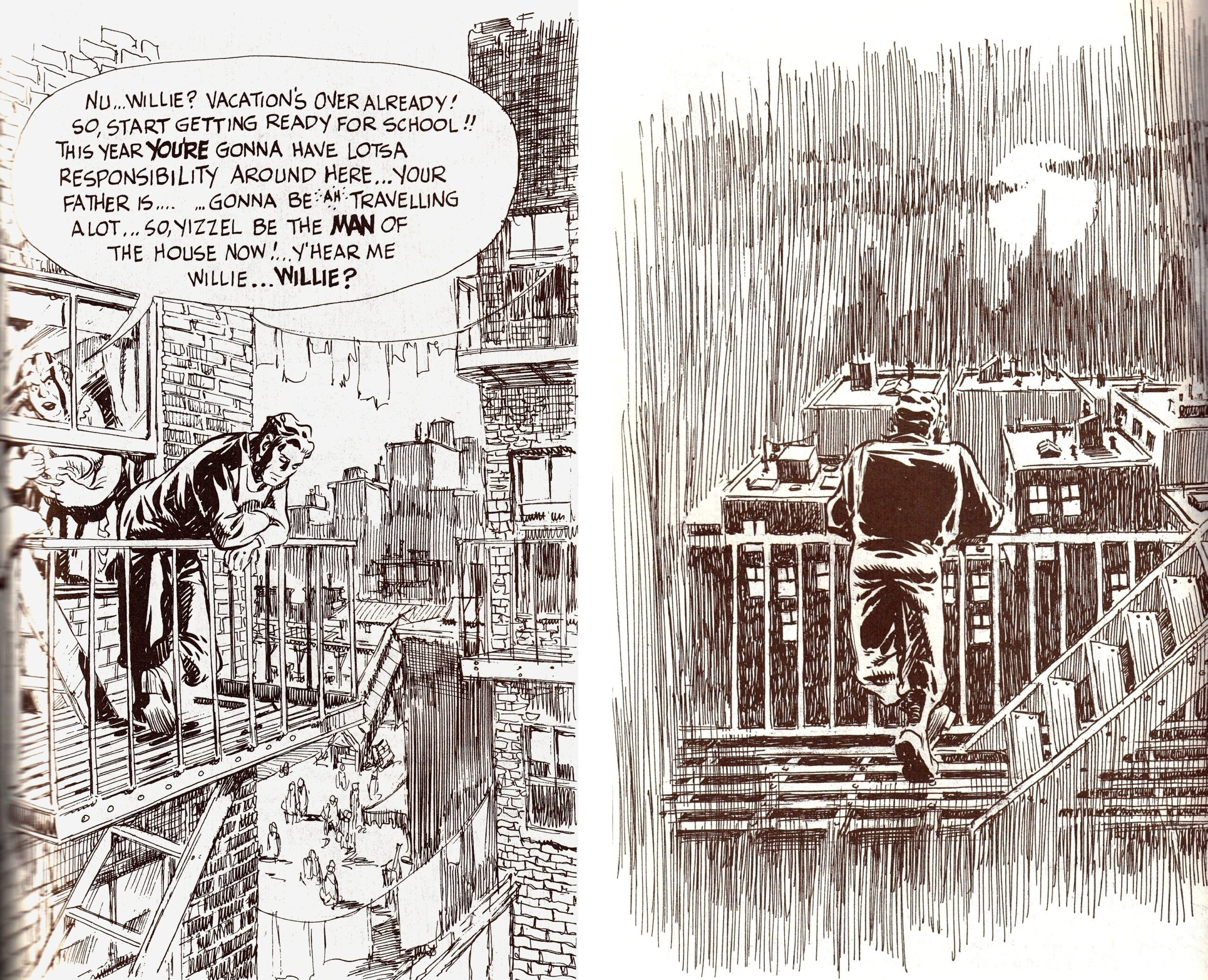

Eisner drew himself as a young man in the tenements at the end of the “Cookalein” story in A Contract With God. (The image on the right was a new illustration for The Contract With God Trilogy in 2006.)

However, he intended them to be more than just reminiscences of the past. As he said in the preface for one graphic novel, he wanted to tell stories in which he could document “themes of Jewish ethnicity and the prejudice Jews still face.”

Eisner, who was Jewish, succeeded.

In honor of Will Eisner’s birth 108 years ago, here is a look at the king of graphic novels and his ruminations on the life he knew.

—

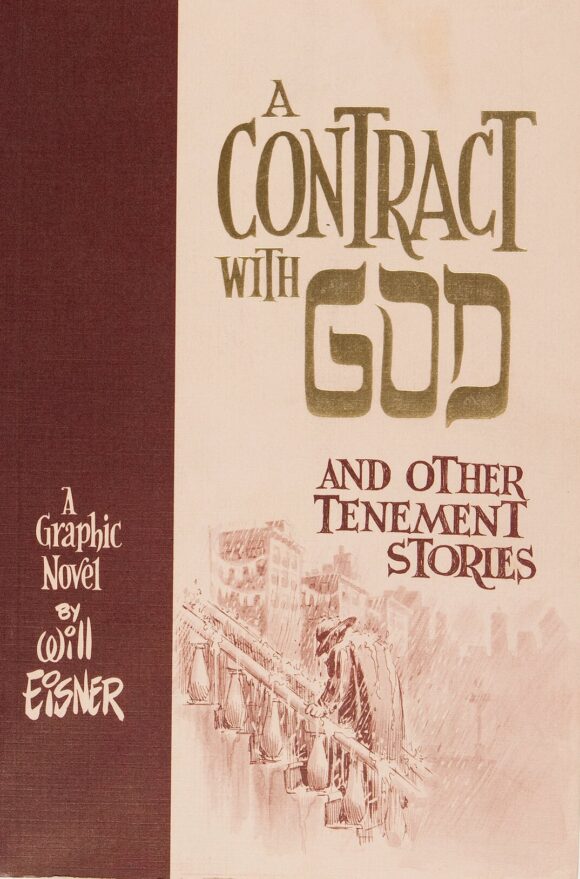

A Contract With God (and Other Tenement Stories), (1978). The gold standard of graphic novels, A Contract With God set the way for Eisner’s new direction in comics storytelling. The opening story came into being because Eisner was deeply mourning the death of his teenage daughter Alice from leukemia. He could not understand how a merciful and just God could take her away from them, and he wrote and drew the powerful tale of a religious Jewish man, Frimme Hersh, returning home to his Dropsie Avenue apartment through a torrential rain and lightning storm that as much as anything equaled his anger at what he considered a broken agreement between him and God to provide a good life if Hersh himself was good.

Other stories in the book were of a street singer with the promise of a great career, a tenement’s amoral caretaker, and the traumatic happenings at a Catskill summer resort where a 15-year-old boy named Willie was vacationing with some members of his family.

—

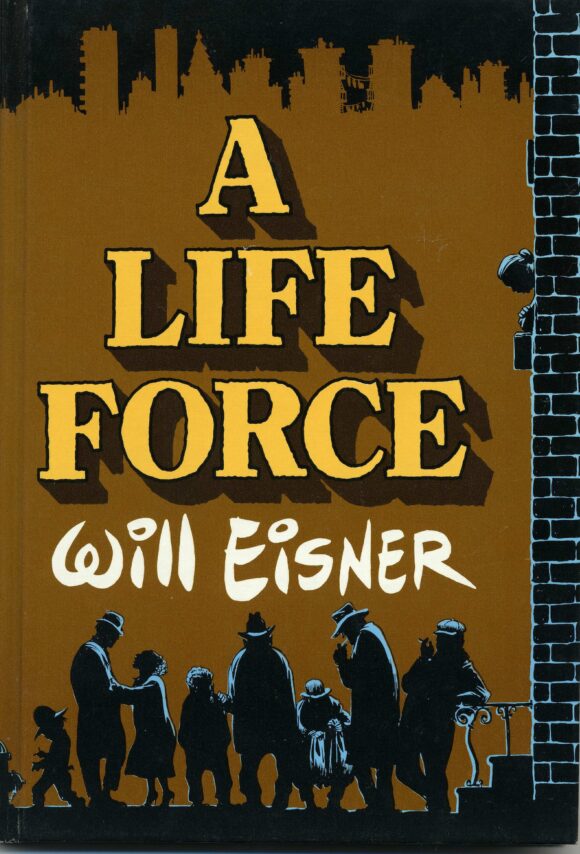

A Life Force (1998). Collected from Will Eisner Quarterly #1 (Winter 1983) through #5 (April 1985), A Life Force is like watching an epic film, with many individual characters who go their own way in life but end up interacting with others in the drama. Starting in the middle of the Depression, A Life Force tells of neglected workers, forbidden love, insanity, communist activities, crime… and a cockroach.

—

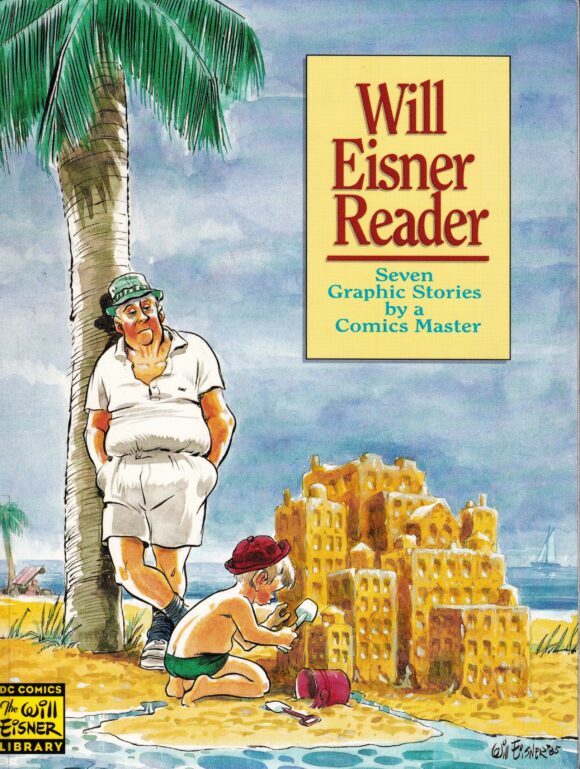

Will Eisner Reader (2000). The Will Eisner Reader is a collection of seven tales that were first published in Kitchen Sink’s Will Eisner Quarterly from #6 (Sept. 1985) to #8 (Mar. 1986). The stories covered a variety of subjects, including one senior’s wistfulness about his past, a marathon, a long-standing underworld contract hit, a deal with Mr. Brimstone, a Franz Kafka tale, and even the emerging humanity of cavemen… as well as several one-page gags about the telephone thrown in just for fun.

—

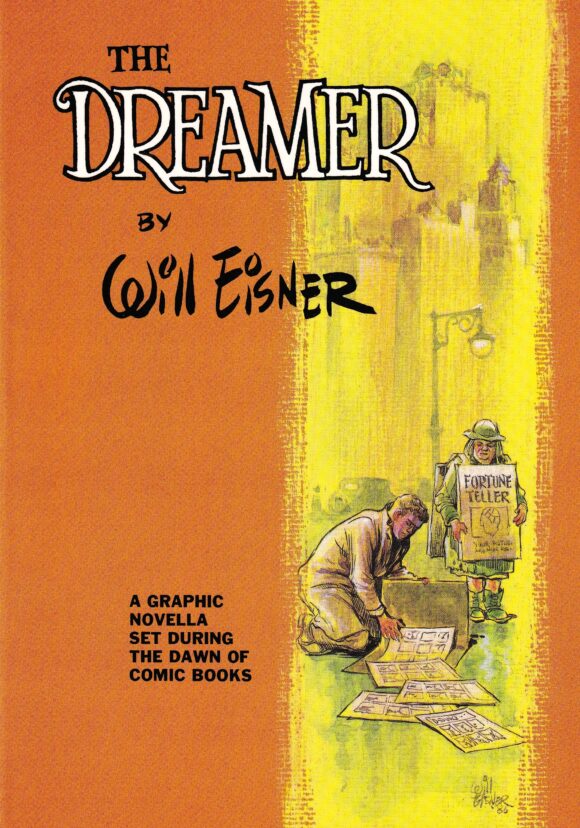

The Dreamer (1986). The Dreamer is a fictionalized take on Will Eisner’s career from the days of working in a printing shop to drawing comics, from organizing a packaging studio to his days of leaving it to do his own comic book that would appear weekly within a newspaper (i.e., what would become The Spirit).

It’s an affectionate tale with young artist Willy Eyron substituting for Eisner; at one point in the story, one of the pseudonyms Eyron uses is Willis Rensie — “Eisner” backward, which is something the illustrator actually used. Overall, The Dreamer is a story of the earliest days of comic books and the people who made them. There is no anger, no viciousness, in Eisner’s portrayal of those days, but plenty of namedropping for those who know the time period, including Jack King (Kirby), Lew Sharp (Lou Fine), and Donald Harrifield (Harry Donenfeld) among them.

—

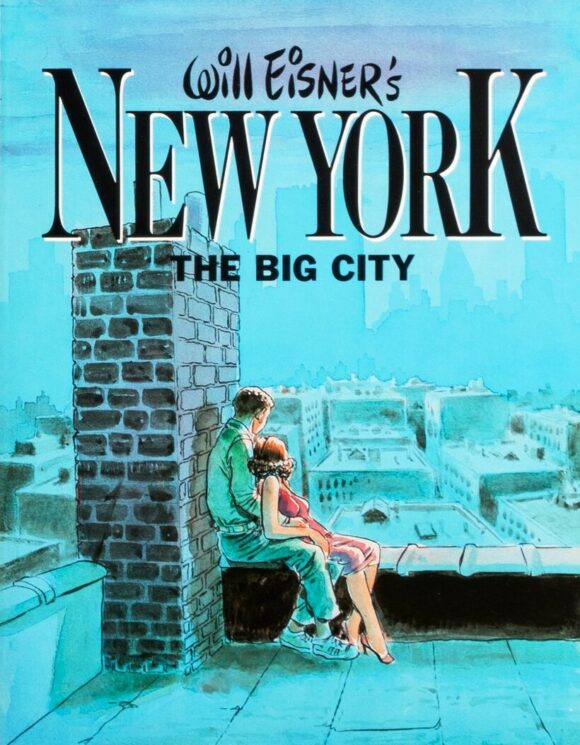

New York, the Big City (1986). In New York, the Big City, Kitchen Sink reprinted a series of 1-to-2-page gags that look similar to Mad magazine’s standalone humor pages, with all taking place in the present-day New York City of the Eighties. These were first published in several issues of The Spirit between 1981-1983 by Kitchen Sink.

—

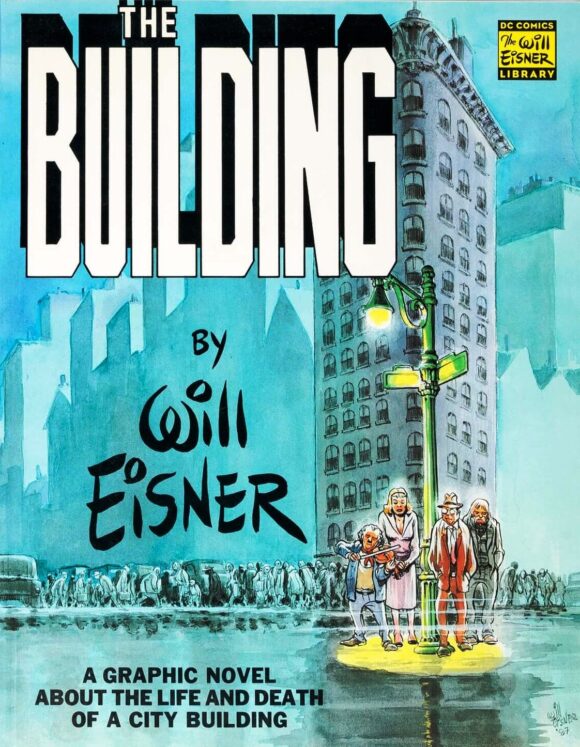

The Building (1987). Eisner postulates than when an old city building is torn down and a new skyscraper is put up in its place, there still remains something of the original there. In this modern-day story, that something is four spirits from the past who had special ties to the old building, some unable to rest because of things they failed to do in life.

—

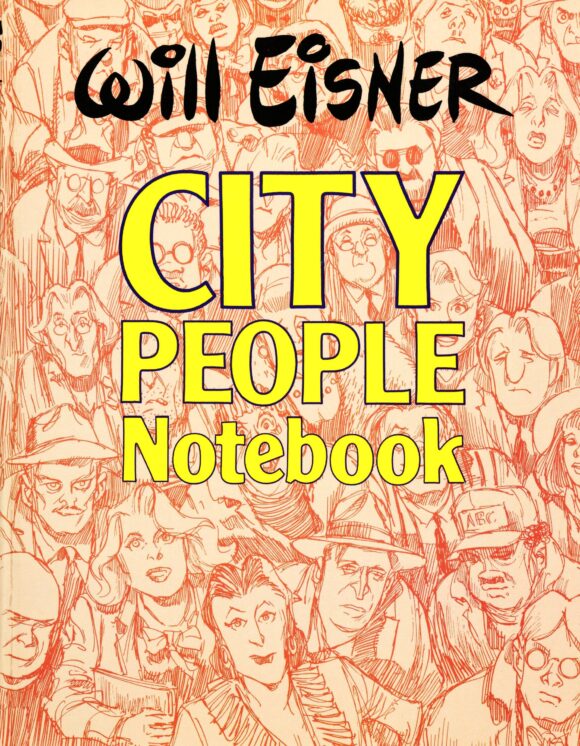

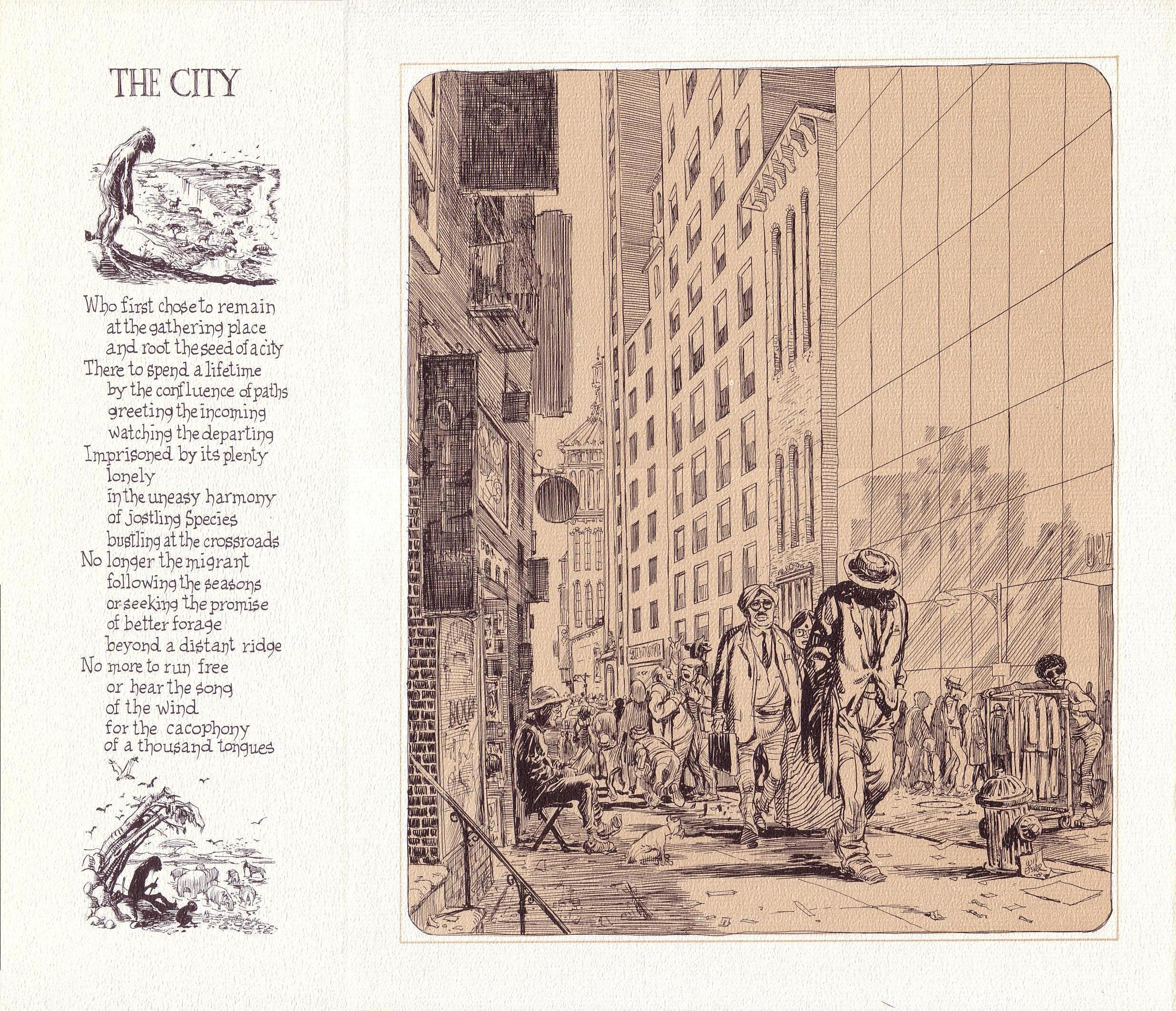

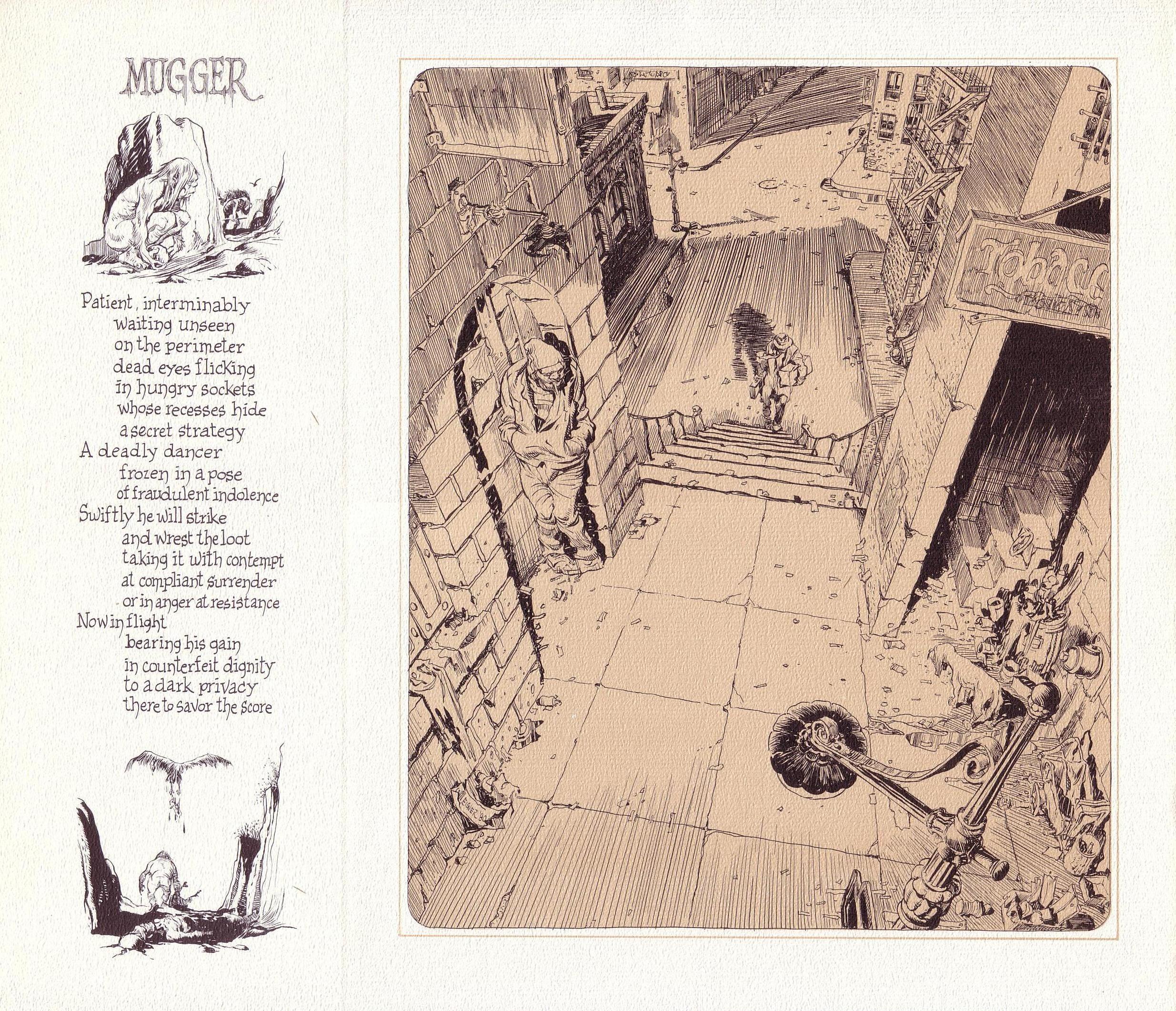

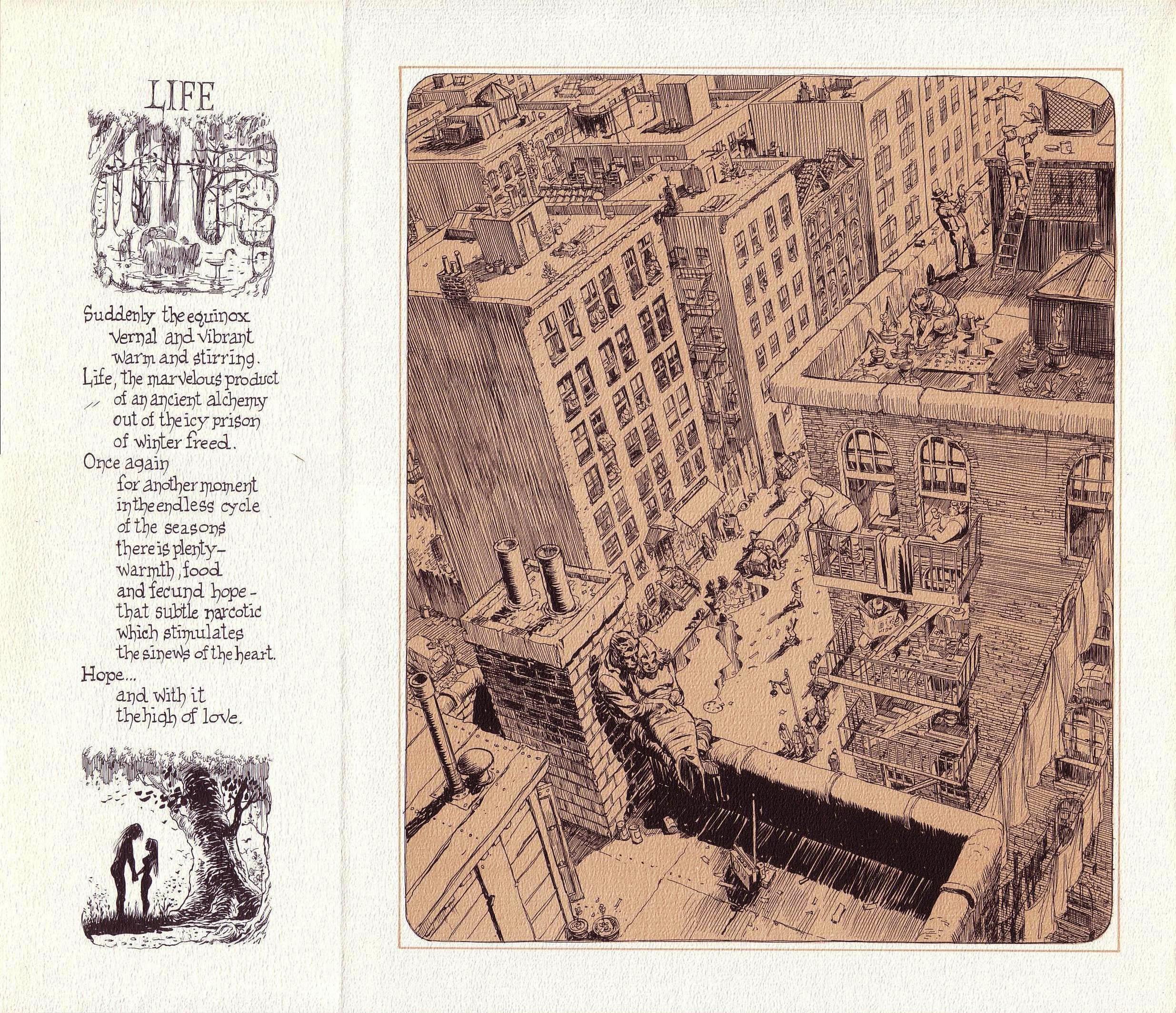

City People Notebook (1989). Eisner goes to his experimental side again, this time in observing New York City’s present-day citizens at their most frantic, in short pieces that often display what made him laugh at human idiosyncrasies. Many times, these vignettes are played completely in drawings without any text.

—

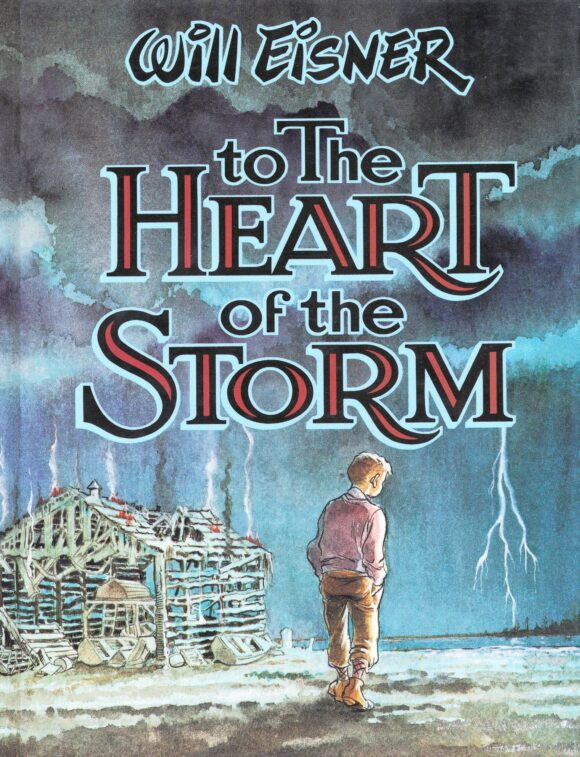

To the Heart of the Storm (1991). In this 200-plus page graphic novel, Eisner illustrated a life dealing with prejudice. During a train ride to an Army camp during World War II, a new recruit named Willie looks out the window, recalling his life to this moment and the bigotry he has faced for being Jewish. The story is a very serious look back to his childhood and growing up in America, and includes tales of his parents’ lives in Europe prior to that.

—

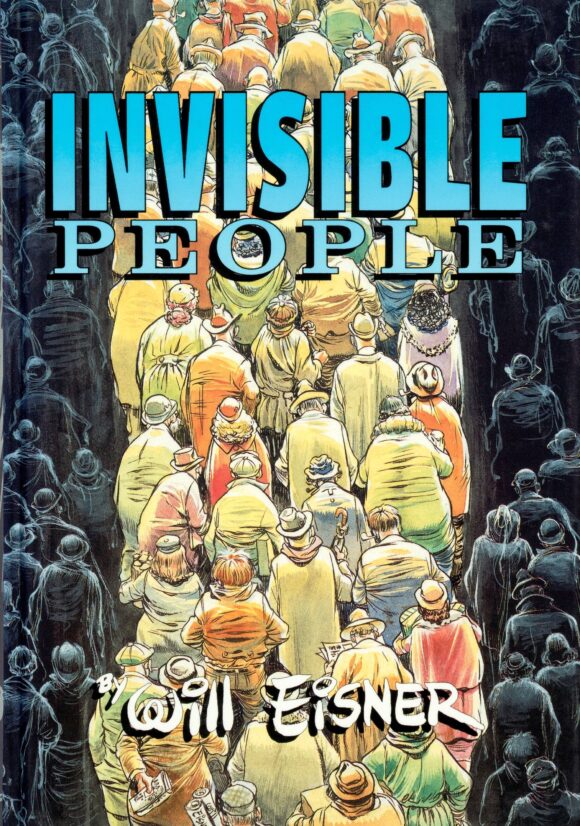

Invisible People (1993). Originally published as a three-issue magazine miniseries in 1992, Eisner explores three subjects in this collection. One is the tale set in the 1930s of a man named Pincus Pleatnik, who from birth just wished not to be noticed, enjoying living in the protection of his anonymity… until the day he noticed a newspaper obituary saying he, of 55 Dropsie Avenue, had died. This results in more sudden attention paid to him than he experienced in his entire lifetime… only he can’t convince people he is still alive!

The second story is about Morris, who achieves fame by having the ability to heal others of their physical problems, but when he fails to do so at the most important moment of his life, he loses everything he has and becomes a homeless person, one of the “invisible” people living on the street. The third tale is one of the saddest, about people who take on the moral responsibility of caring for ailing family members… but lose the chance to live their own lives along the way.

—

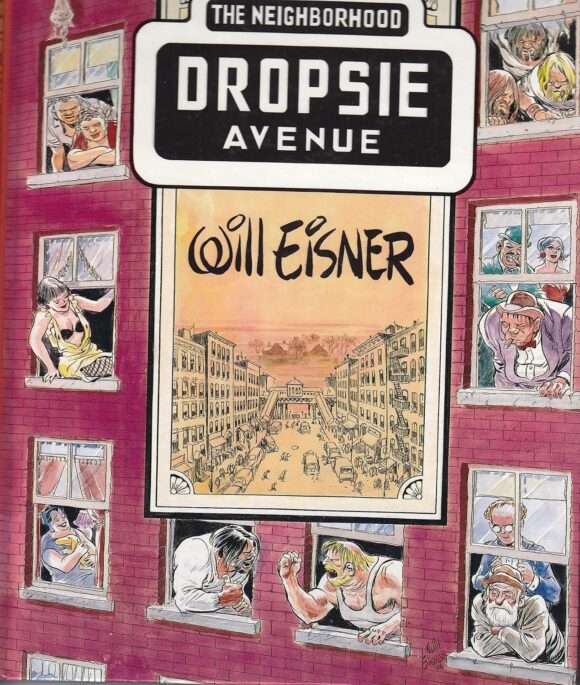

Dropsie Avenue: The Neighborhood (1995). Though A Contract With God has received the most attention, I feel that Dropsie Avenue: The Neighborhood is his masterpiece. It’s a history of 100 years of the Bronx in one small housing district — in particular, in or near his favorite location of 55 Dropsie Avenue. The story contains all the things that Eisner is justly famous for putting in a tale: drama, humor, romance, politics, big and small business dealing, religion, and more. One of the most amusing repetitions in the story is how he demonstrates the current occupants’ prejudices about a different culture moving into the neighborhood. From the very beginning with the original Dutch settlers’ feelings against the English, then the English against the Irish, followed likewise by Germans, Italians, and Jews.

Each time, those ethnic mixes assimilate into the neighborhood and together they join in to bemoan more “invaders” — including the arrival of Latinos, Blacks, and the hippie movement, all of whom become part of the area before it gets torn down and rebuilt from scratch. As Eisner said, “Dropsie Avenue is a story of life, death, and resurrection.”

—

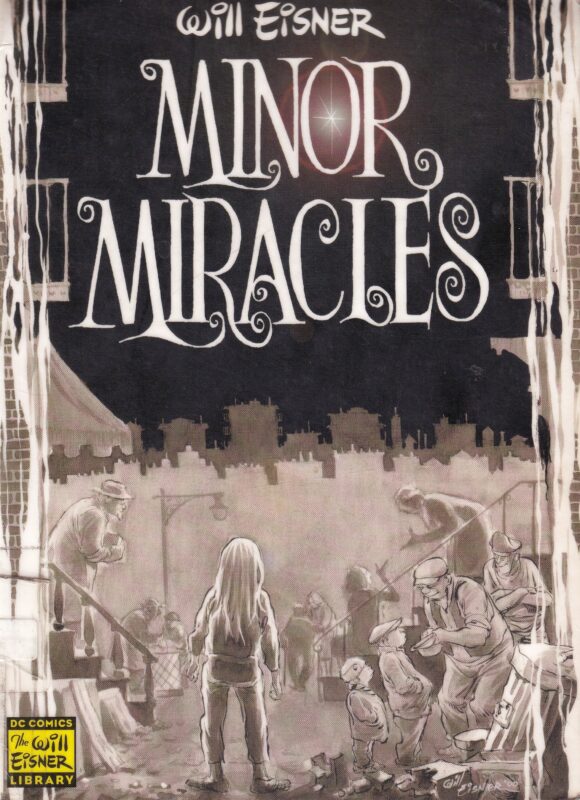

Minor Miracles (2000). Eisner remembered from his childhood when the neighborhood was a place – as the title suggests – of minor miracles, when something would happen that would make things different, often better, but not always. It’s an overall charming group of stories, including a man who uses guilt to separate relatives from their money, a young boy who outsmarts bullies on his street, and a crippled man marrying a deaf-and-mute woman. The centerpiece, though, is the tale of a homeless young boy wandering into the vicinity and improving people’s lives through his presence.

—

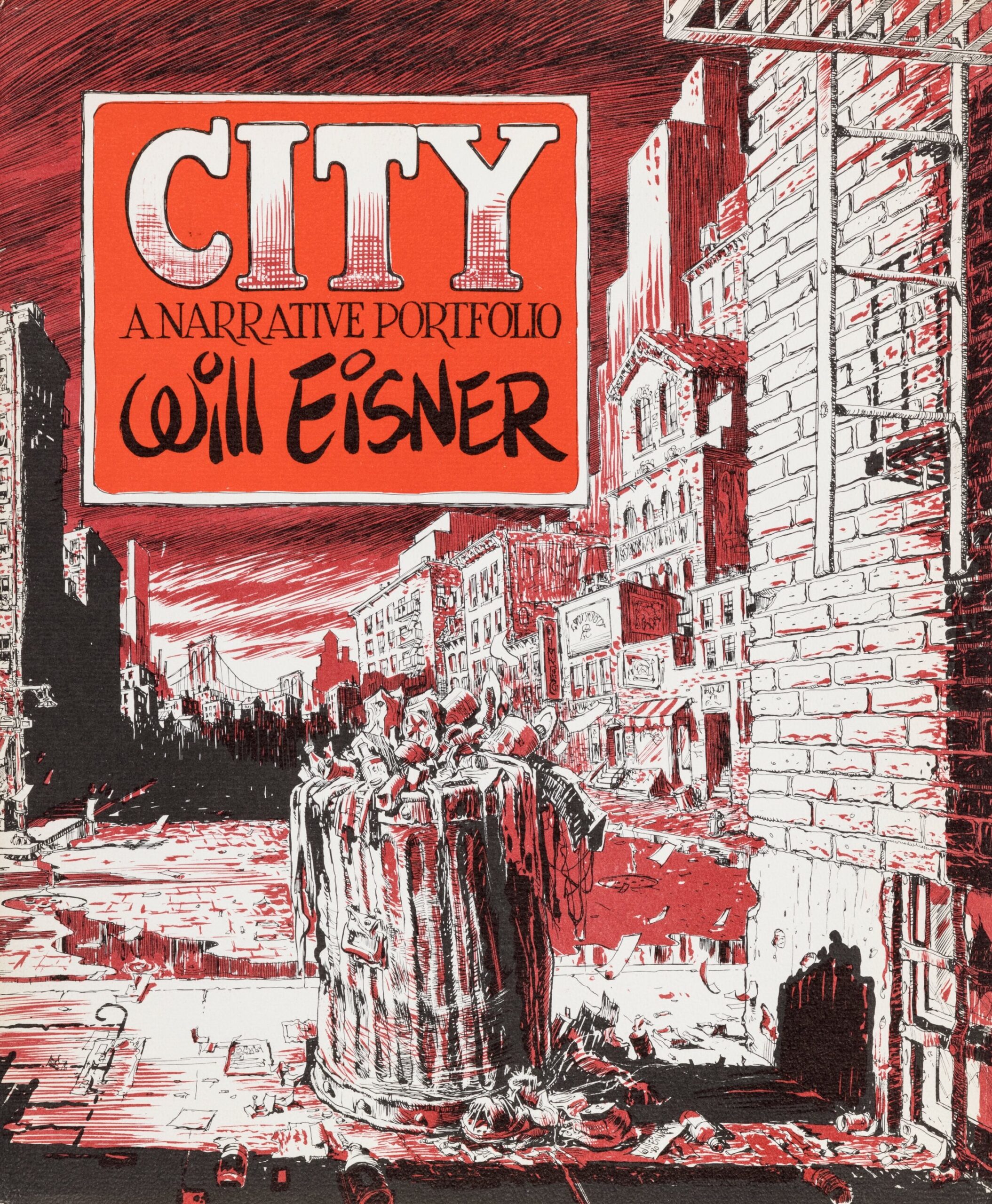

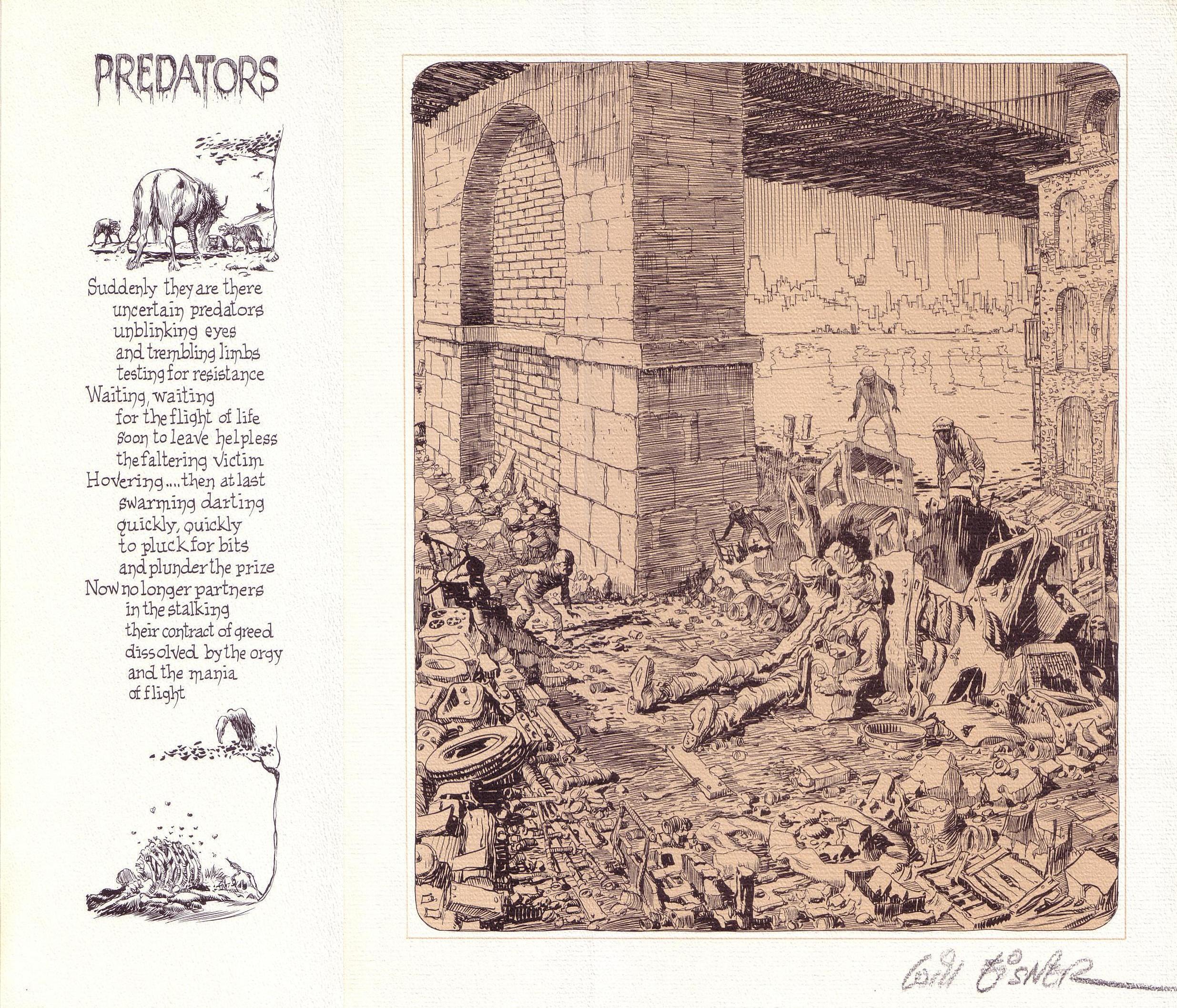

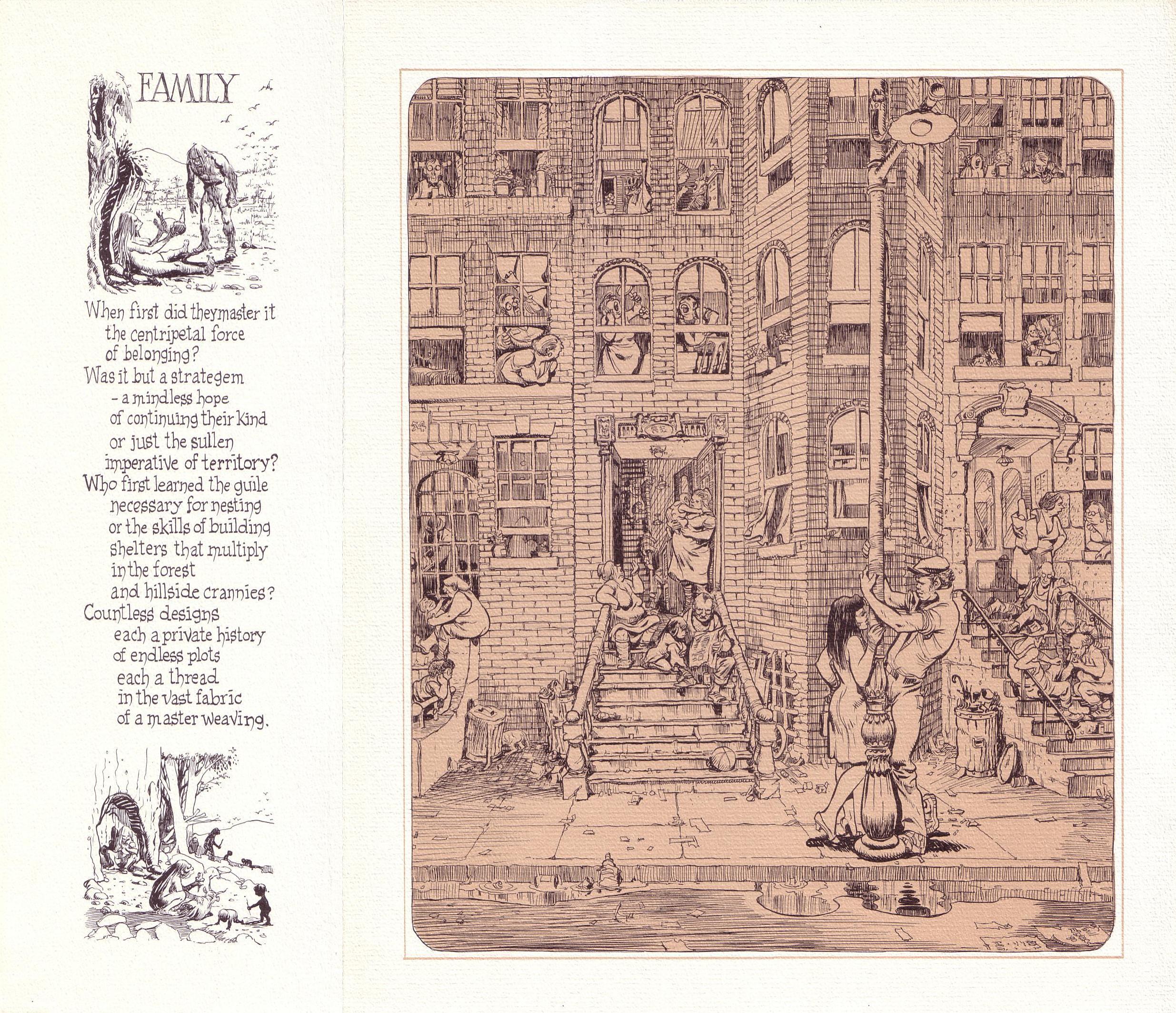

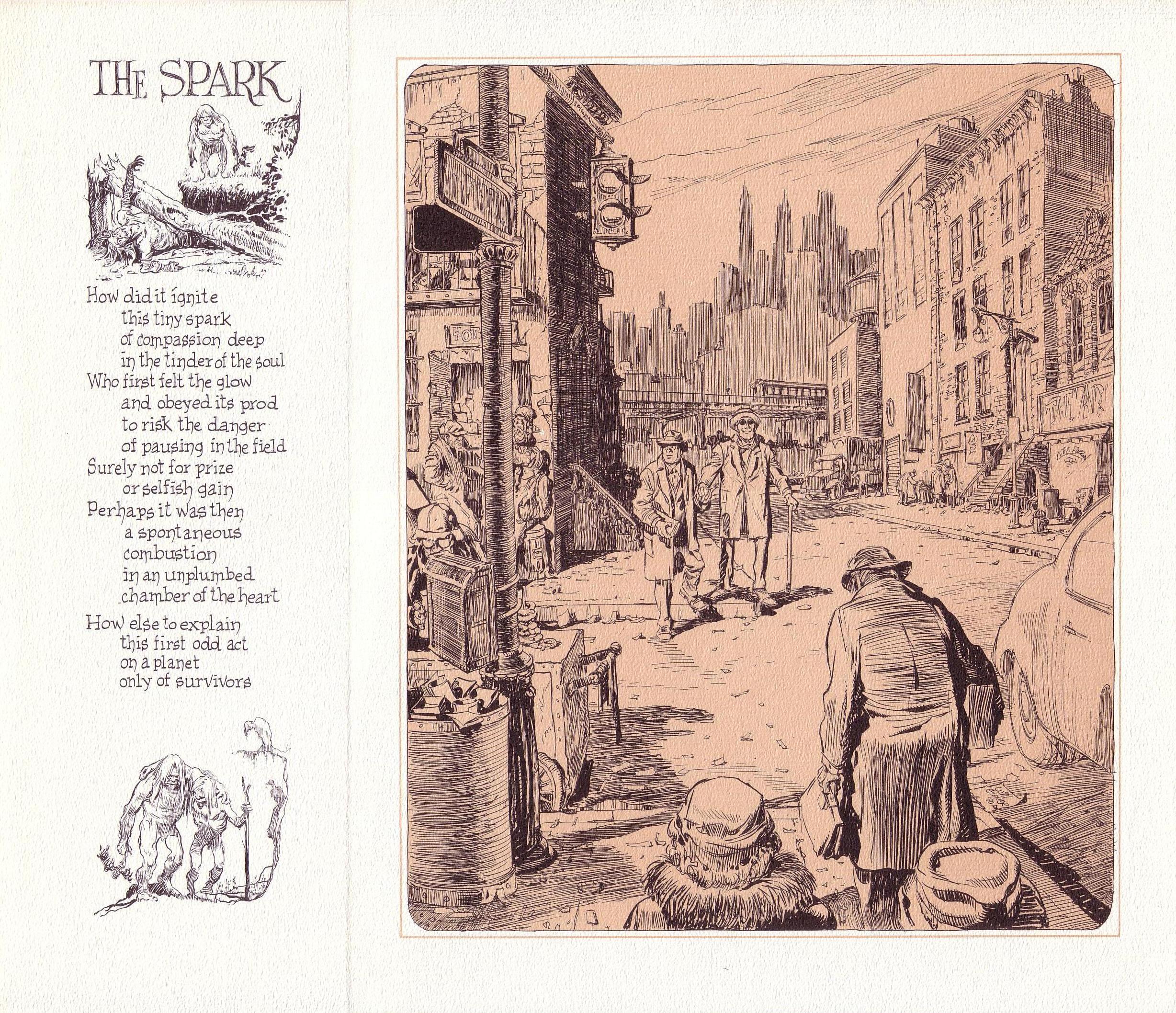

BONUS: One special addition in those years of telling New York tales was City: A Narrative Portfolio (1980), with six prints showcasing some of Eisner’s most magnificent artwork while adding text-and-illo comparisons of the early days of mankind alongside the present.

We were the benefactors of Eisner’s greatness during his lifetime with his stories of humanity in his graphic novels, as well as the many years of The Spirit. Both of these continue to see reprints after his death 20 years ago in 2005.

One thing many artists and writers hope for is that their work will live long past their demise, and this certainly is what has happened with Will Eisner.

—

MORE

— DARWYN COOKE: The WILL EISNER Stories Every Fan Should Read. Click here.

— A WILL EISNER SALUTE: 13 Lethal Ladies of THE SPIRIT. Click here.

—

13th Dimension contributor-at-large PETER BOSCH’s first book, American TV Comic Books: 1940s-1980s – From the Small Screen to the Printed Page, was published by TwoMorrows. (You can buy it here.) A sequel, American Movie Comic Books: 1930s-1970s — From the Silver Screen to the Printed Page, is due in 2025. (You can pre-order here.) Peter has written articles and conducted celebrity interviews for various magazines and newspapers. He lives in Hollywood.

March 6, 2025

Damn ! He was so good. I’m going to have to break out some of my Eisner comics.

Time for a re-read. Great post !

March 6, 2025

Thanks!

March 7, 2025

What a great review. I came to Eisner’s work very late in my own life. I need to go find some of these books you have outlined here. He was such a talent. Peter, always enjoy your stuff.