PAUL KUPPERBERG: It’s the seminal book’s 60th ANNIVERSARY…

By PAUL KUPPERBERG

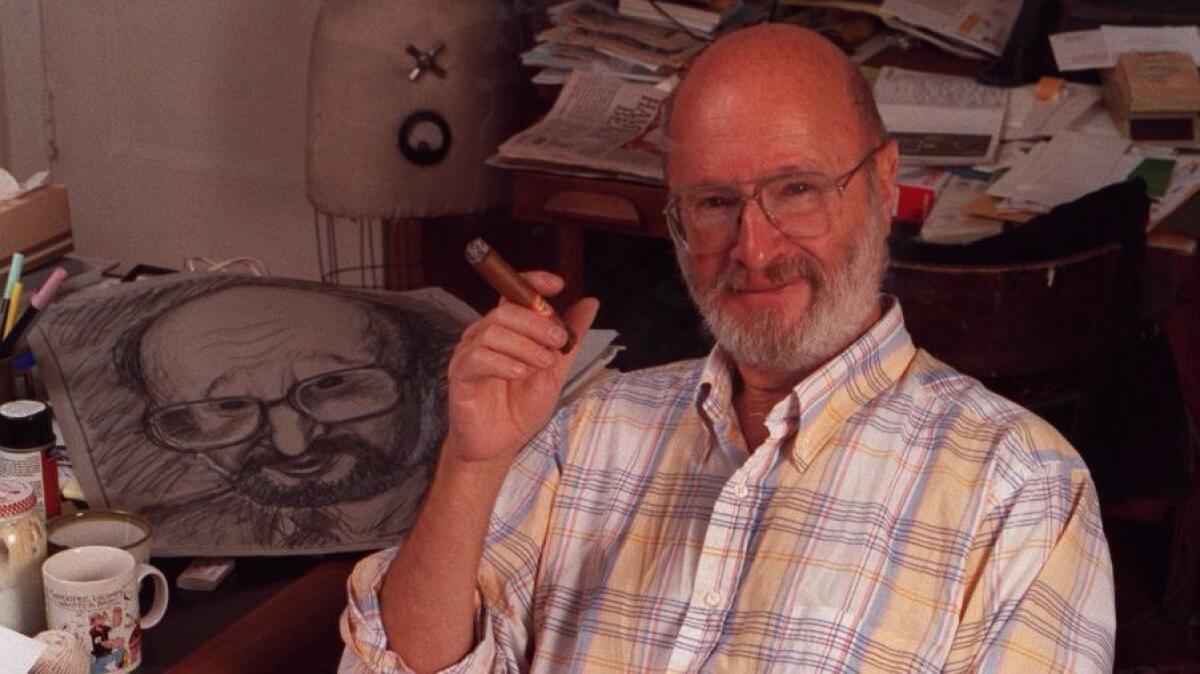

If all Jules Feiffer (January 26, 1929 – January 17, 2025) had done was the 41 years (1956 – 1997) of the weekly comic strip Feiffer for The Village Voice, it would have been enough.

If all Jules Feiffer had done was write more than 35 books, plays, and screenplays, including Harry the Rat With Women (1963), Little Murders (1967), and Carnal Knowledge (1971), it would have been enough.

If all Jules Feiffer had done was win an Academy Award in 1961 for his short animated film Munro, or be awarded the 1986 Pulitzer Prize for political cartoons, or in 2004 be inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame and receive the National Cartoonists Society’s Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award, or Lifetime Achievement Awards from the Writers Guild of America (2010) and the Dramatists Guild of America (2023), it would have been enough.

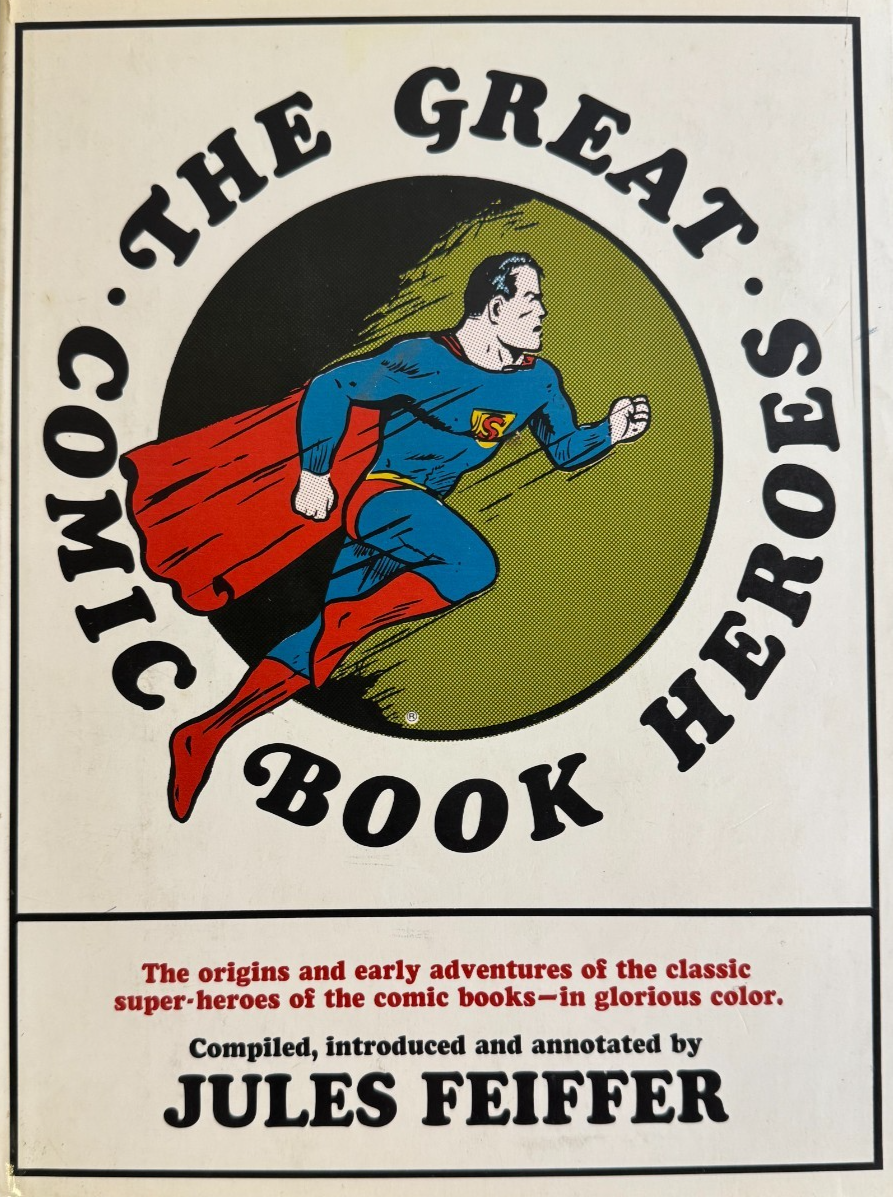

And if all Jules Feiffer had done was pen his autobiography, Backing Into Forward: A Memoir (2010) about his remarkable life and career, it would have been enough… but Jules Feiffer also “compiled, introduced, and annotated The Great Comic Book Heroes — released 60 years ago, on Nov. 15, 1965 — one of the most influential books about comics for a couple of generations of comic book creators.

In 1965, the Golden Age of Comics (let’s call it 1935 – 1956) wasn’t that far in the past, but when it came to the availability of Golden Age stories, it might as well have been in a different century. DC and Marvel might occasionally publish a Golden Age reprint in an 80-Page Giant or annual, but old comic books were hard to come by and even when you did find them, those issues could cost $2, $3, even $5 a pop. Younger readers like me (I was born in 1955) were teased with revivals of the heroes of the Golden Age or references to the past in letter columns, but with few exceptions, the stories themselves remained elusive… and then came The Great Comic Book Heroes!

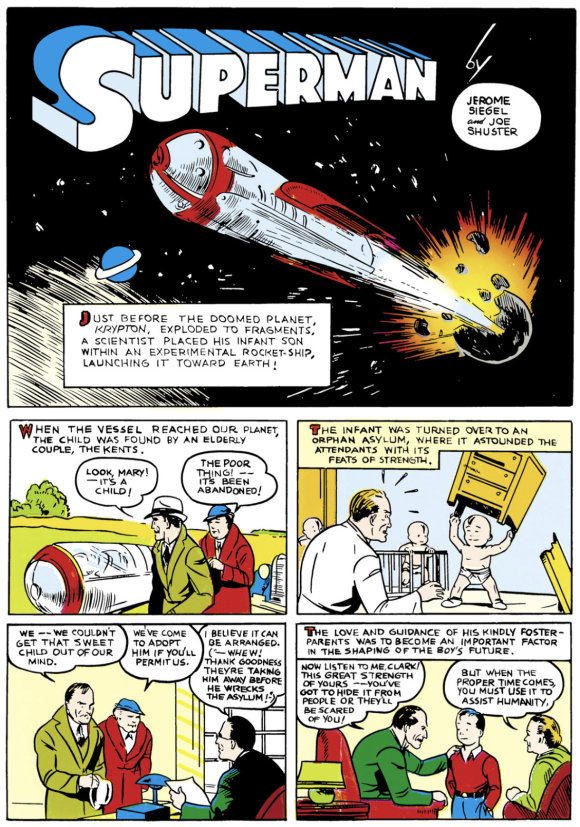

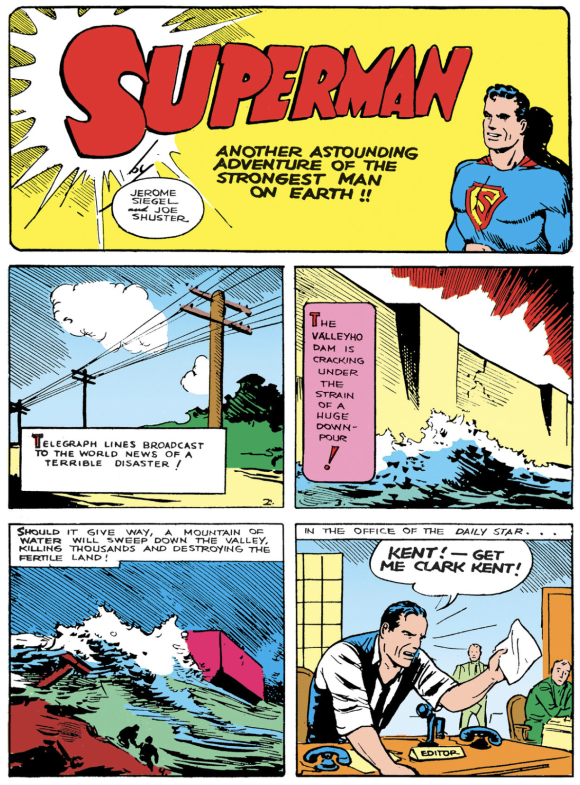

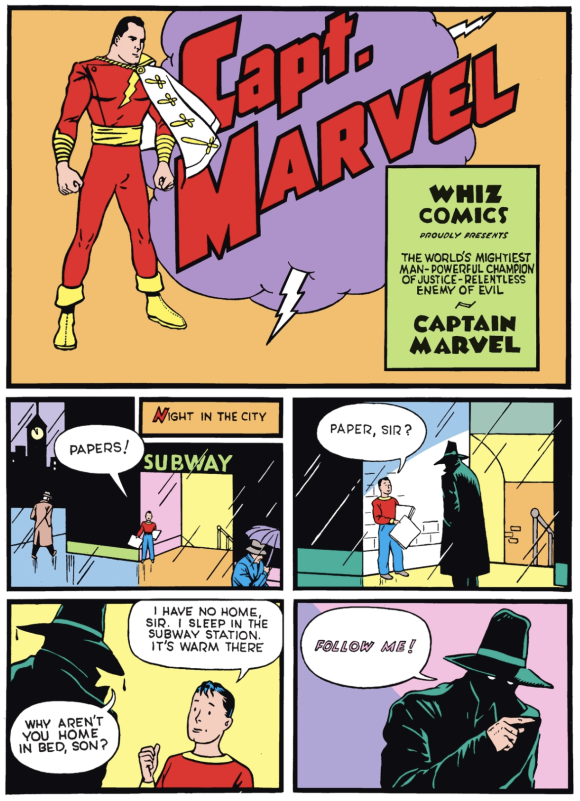

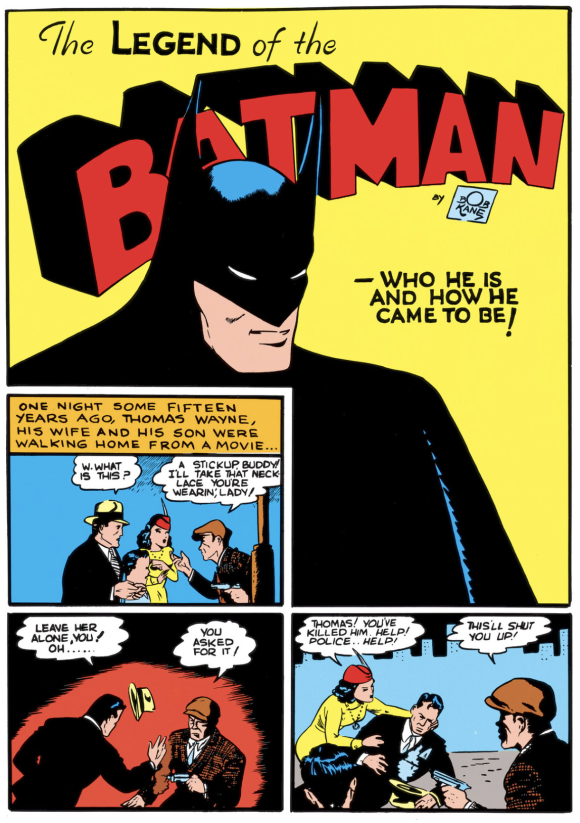

My friend Steve and I discovered the book in the Utica Avenue branch of the Brooklyn Public Library in early 1968. This hardcover coffee-table book (first published by Dial Press) with a dustjacket emblazoned with an image of the Golden Age Superman leaping across the cover, promised “the origins and early adventures of the classic super-heroes of the comic books—in glorious color.” It would become my personal comics Rosetta Stone, not only for the 13 stories it reprinted “in glorious color,” but for Feiffer’s introduction and afterword to the material.

I had no idea who Jules Feiffer was at the time other than what the 50-words-or-less biographical blurb on the flap of the dustjacket told me about him, but once I read his essays bookending the reprints, I came away with three things:

First, Jules Feiffer was, like me, a fan, who not only read comic books (and comic strips), but also wrote and drew his own comic books as a pre-adolescent!

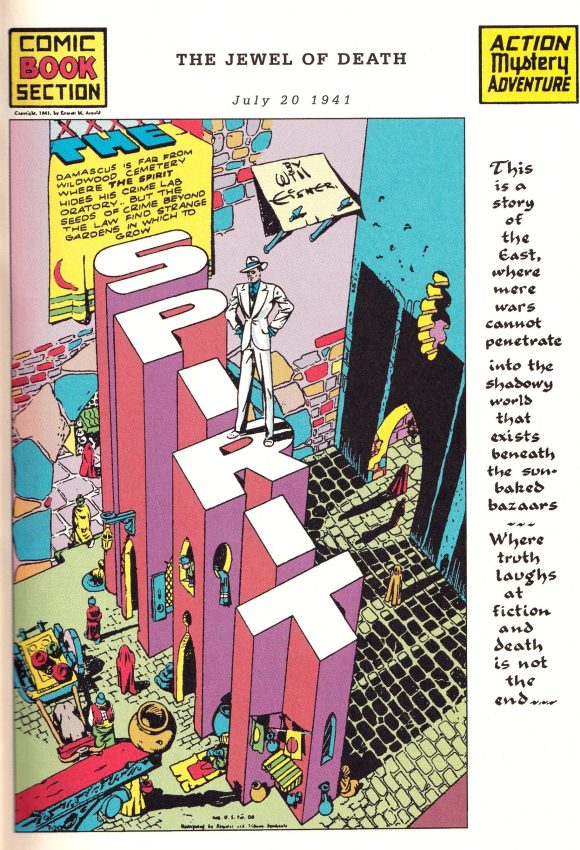

Second, with his evolution as a fan through the 1930s and 1940s, leading to an apprenticeship and regular employment under Will Eisner on The Spirit (a comic strip I’d never heard of until I read the one reprinted in this volume), Feiffer was uniquely qualified to write about the struggle of surviving in those days of yore.

Third, I wanted to do what Jules Feiffer did!

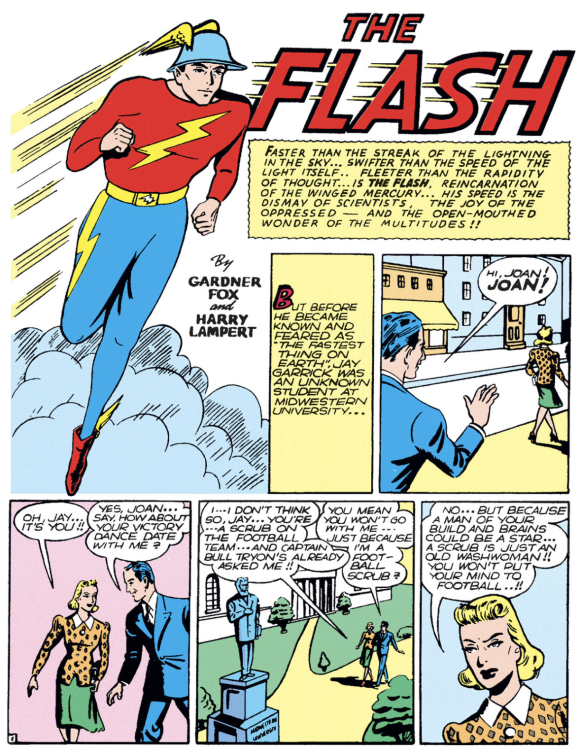

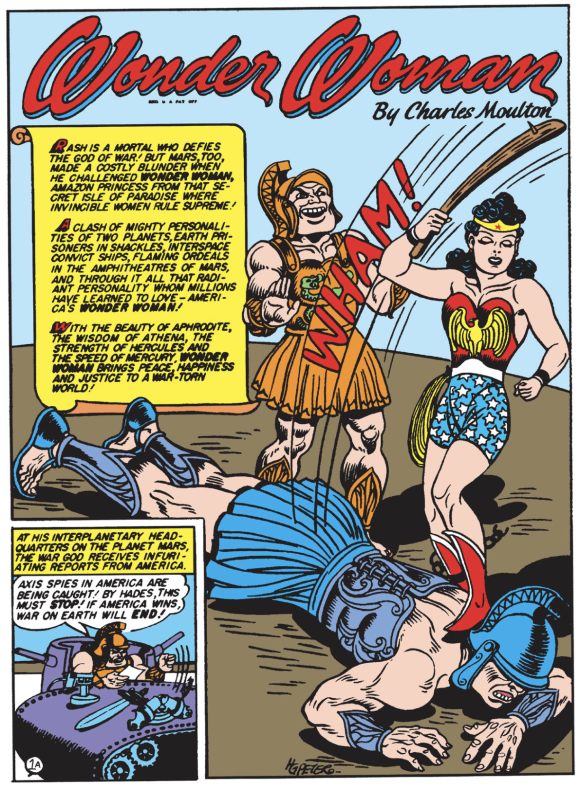

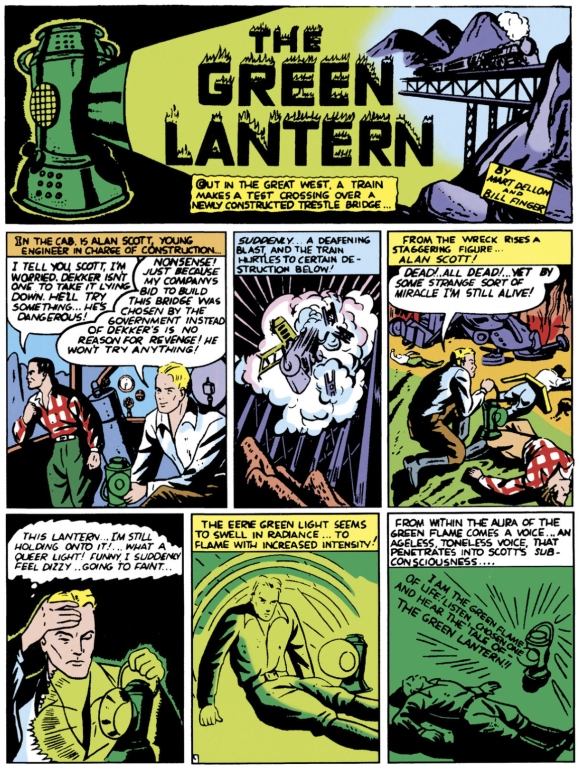

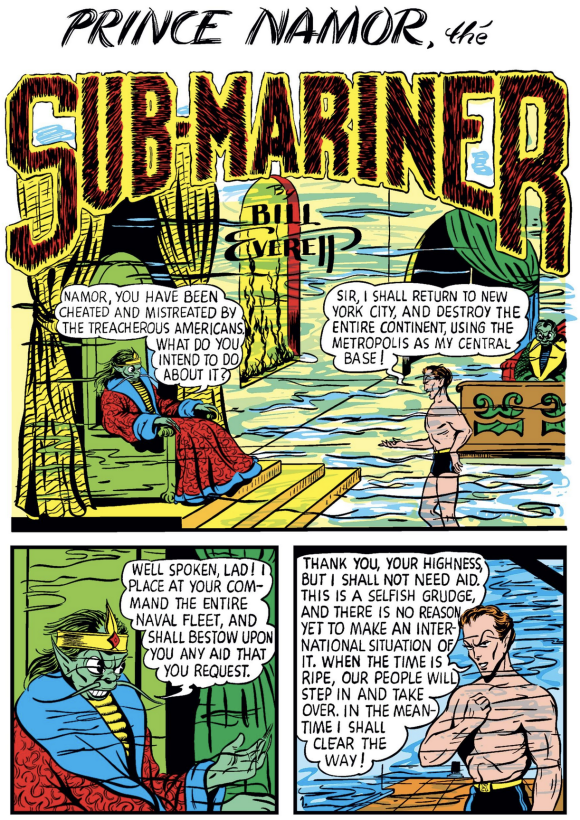

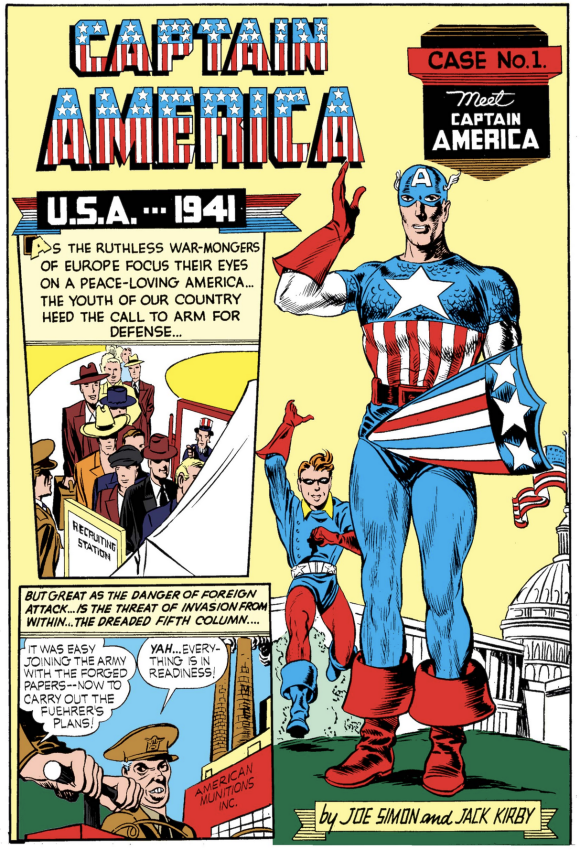

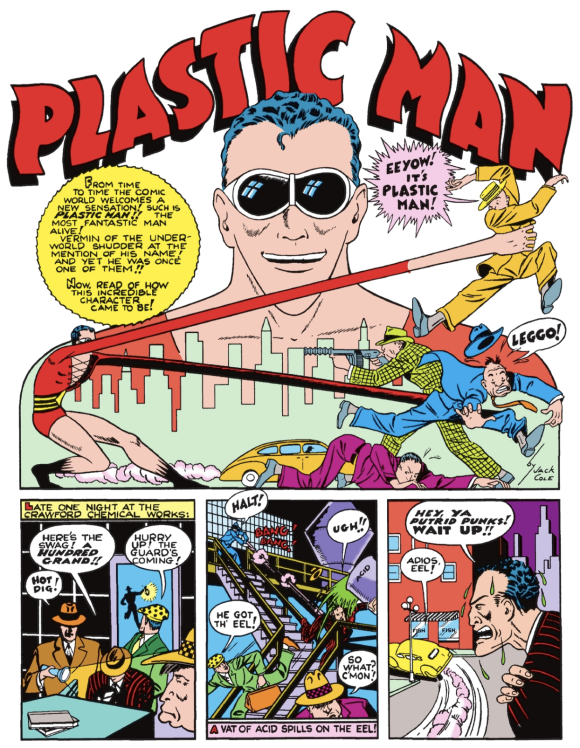

As happy as I was to have the book for its groundbreaking line-up of “the origins and early adventures of the classic super-heroes” originally published by competitors DC Comics (Superman, Batman, the Flash, Green Lantern, the Spectre, Hawkman, and Wonder Woman), Timely Comics (Human Torch, Sub-Mariner, and Captain America), Fawcett (Captain Marvel), Quality Comics (Plastic Man), and Eisner (the Spirit), it was Feiffer’s introductory material that I cherished. Steve and I alternated checking it out of the library so it could be read and reread, intro and stories alike, from cover to cover.

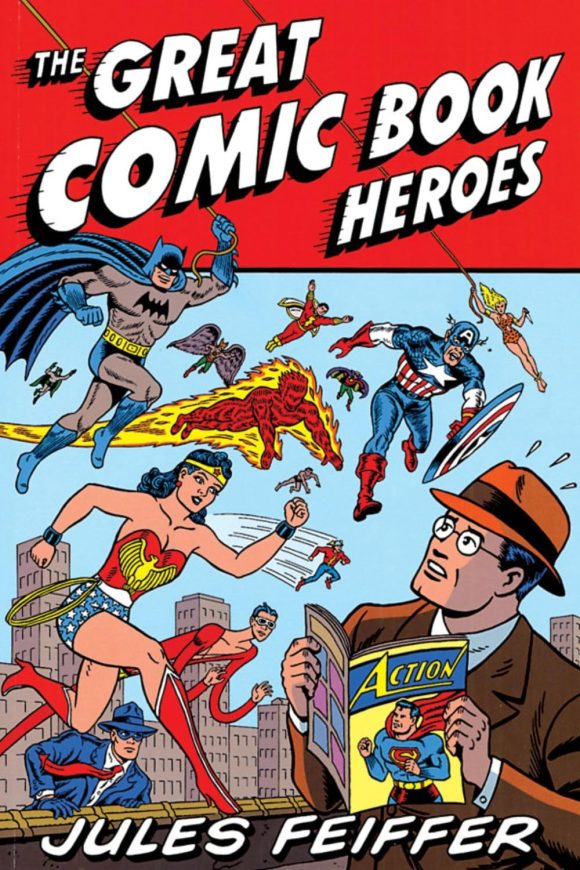

2003 edition

And, as it turns out, I wasn’t the only one to come away from Great Comic Book Heroes motivated to make a life in comic books. As I got older and met other fans and, later, professionals, I discovered there weren’t many creators “of a certain age” who hadn’t come across Feiffer’s book and fewer still who hadn’t been influenced by it. In 2025, 60 years since its publication, it remains the most often cited book in my interviews with comics creators from across several decades for my books Direct Comments and Direct Creativity.

(The Great Comic Book Heroes is long out of print, but copies of various hardcover editions can be found relatively inexpensively on eBay, and there is a 2003 paperback version containing only the text that was published by Fantagraphics Books. You can also read the text online, courtesy of The Comics Journal. (All quotes copyright © the estate of Jules Feiffer.)

Here then, MY 13 FAVORITE QUOTES FROM JULES FEIFFER’S THE GREAT COMIC BOOK HEROES, accompanied by various splash pages that were published in the book:

(By the way, this week’s RETRO HOT PICKS shows what else came out this week.)

—

1. “Grown-ups still wielded all the power, still could not be talked back to, still were always right however many times they contradicted themselves. By eight I had become a politician of the grown-up, indexing his mysterious ways and hiding underground my lust for getting even until I was old enough, big enough, and important enough to make a bid for it. That bid was to come by way of a career — (I knew I’d never grow big enough to beat up everybody; my hope was to, somehow, get to own everything and fire everybody). The career I chose, the only one that seemed to fit the skills I was then sure of — a mild reading ability mixed with a mild drawing ability — was comics.”

Substitute “mild writing ability” for “mild drawing ability” … and change “eight” to “ten or eleven” (I wasn’t nearly as precocious as Feiffer) but this pretty much summed me up.

—

2. “The world of comics was a form of visual shorthand, so that the average hero need not have been handsome in fact, so long as his face was held to the required arrangement of lines that readers had been taught to be the accepted sign of handsome: sharp, slanting eyebrows, thick at the ends, thinning out toward the nose, of which in three-quarter view there was hardly any—just a small V placed slightly above the mouth, casting the faintest nick of a shadow. One never saw a nose full view. … Most heroes, whatever magazine they came from, looked like members of one or two families: Pat Ryan’s or Flash Gordon’s. Except for the magicians, all of whom looked like Mandrake. The three mythic archetypes.”

“Visual shorthand” and “mythic archetypes” were terms that sent me to consult the dictionary, but they really did help me understand what it was I’d been looking at and reading all this time.

—

3. “I studied styles.”

I remember the pride I felt the first time I opened a previously unread comic book and was able to identity the artist as Carmine Infantino solely from his style! I also started studying the styles of the stories themselves, to be able to identity the writer by the way he wrote. That part was harder.

—

4. “Remember, Kent was not Superman’s true identity as Bruce Wayne was the Batman’s or (on radio) Lamont Cranston the Shadow’s. Just the opposite. Clark Kent was the fiction. … The Lone Ranger needed an accoutrement white horse, an Indian, and an establishing cry of Hi-Yo Silver to separate him from all those other masked men running around the West in days of yesteryear. But Superman had only to wake up in the morning to be Superman. In his case, Clark Kent was the put-on.”

Wait. What? Superman had a secret identity to protect his friends and loved ones from harm by his enemies… didn’t he? I think this may have been one of the first times anyone applied this kind of dissection of the trope and it kind of blew my little adolescent mind.

—

5. “The problem with other super-heroes was that the most convenient way of becoming one had already been taken. Superman was from another planet… The answer, then, rested with science. That strange bubbly world of test tubes and gobbledy-gook which had, in the past, done such great work in bringing the dead back to life in the form of monsters — why couldn’t it also make men super?”

This was an obvious statement of fact backed up by the scores of science-based superheroes I regularly read like the Flash, the Atom, Green Lantern, and just about every Marvel character, but seeing it in print solidified the idea in my nascent writer’s brain and started me thinking about the other obvious ideas I might have been overlooking.

—

6. “Fiction House books had a boxed, constipated look. Balloons were rectangular, restricted-looking. Anybody knew — or should have known — that good balloons were scalloped bubbles floating light as air on the tops of panels. Free and imaginative. Rectangular balloons were depressants—something architectural-looking about them; something textbooky.”

My two revelatory takeaways from this: (1) Oh, “balloons,” that’s what they’re called, and (2) different companies had different styles, not only in the artists they used but in how their comic books looked; later, Feiffer referred to Quality Comics as “the Warner Brothers of the business,” a vivid analogy for the world of comic books, that I extended to including DC as MGM, Marvel as RKO, and Charlton as Republic. Your analogies may vary.

—

7. “[Will Eisner’s] high point was The Spirit, a comic book section created as a Sunday supplement for newspapers. It began in 1939 and ran, weekly, until 1942, when Eisner went into the army and had to surrender the strip to (the joke is unavoidable) a ghost.”

Talk about understatements. Eisner went into the Army, but The Spirit would continue, ghosted by the likes of Lou Fine, Manly Wade Wellman, William Woolfolk, and Jack Cole until his return, and would run until late 1952… with a young Jules Feiffer writing most of the strips beginning in 1950. But the 1941 Spirit story that rounds out the Great Comic Book Heroes reprints was a shock to my system. After 120 pages of standard superhero stories, Eisner’s eight-pager was a plunge into cold, clear, exotic waters, more Casablanca than The Adventures of Superman.

—

8. “But, of course, once a hero turns that vulnerable, he loses interest to both author and readers. The Spirit, through the years, became a figurehead, the chairman of the board, presiding over eight pages of other people’s stories. An inessential do-gooder, doing a walk-on on page eight, to tie up loose strings. A masked Mary Worth.”

Another buried lesson in storytelling, one I got immediately because I got the Mary Worth reference, about the newspaper strip starring a well-intentioned buttinsky that I read not because I cared about the character but because I read all of the comic strips in the newspaper just because they were there.

—

9. “In Seduction of the Innocent, psychiatrist Frederic Wertham writes of the relationship between Batman and Robin: ‘They constantly rescue each other from violent attacks by an unending number of enemies. The feeling is conveyed that we men must stick together because there are so many villainous creatures who have to be exterminated… Sometimes Batman ends up in bed injured and young Robin is shown sitting next to him. At home they lead an idyllic life. They are Bruce Wayne and “Dick” Grayson… They live in sumptuous quarters, with beautiful flowers in large vases… Batman is sometimes shown in a dressing gown… It is a wish dream of two homosexuals living together.’”

Reading this — my first exposure, as it were, to Dr. Wertham and his poisonous ideas — as a 12- or 13-year old in the relatively sheltered 1960s, I knew it was wrong. The matter of whether or not Bruce Wayne and/or Dick Grayson were gay aside, the living arrangement he described wouldn’t have been so much “a wish dream of two homosexuals living together” as it would be a pedophile’s dream of a grown man keeping an underaged boy toy. I only knew the term “child molester” and I knew Bruce Wayne wasn’t that. He was Batman, for crying out loud!

—

10. “Artists sat lumped in crowded rooms, knocking it out for the page rate. Penciling, inking, lettering in the balloons for $10 a page, sometime less; working from yellow typescripts which on the left described the action, on the right gave the dialogue. A decaying old radio, wallpapered with dirty humor, talked race results by the hour. Half-finished coffee containers turned old and petrified. The ‘editor,’ who’d be in one office that week, another the next, working for companies that changed names as often as he changed jobs, sat at a desk or a drawing table—an always beefy man who, if he drew, did not do it well, making it that much more galling when he corrected your work and you knew he was right. His job was to check copy, check art, hand out assignments, pay the artists money when he had it, promise the artists money when he didn’t. Everyone got paid if he didn’t mind going back week after week. Everyone got paid if he didn’t mind occasionally pleading.”

May I please have some more, sir! I can’t tell you how absurdly romantic this all sounded, how much I wanted to be a part of that sorry mob determined to make comic books no matter what!

—

11. “We were a generation. We thought of ourselves the way the men who began movies must have. We were out to be splendid — somehow.”

Thirty years later, almost a decade after I first read this and grew jealous of what I’d missed by being born too late, I would become part of a generation that left its mark on comics.

—

12. “If the place being used had a kitchen, black coffee was made and remade. If not, coffee and sandwiches were sent for — no matter the hour. In mid-town Manhattan something always had to be open. Except on Sundays. A man could look for hours before he found an open delicatessen. The other artists sat working, starving: some dozing over their breadboards, others stretching out for a nap on the floor, their empty fingers twitching to the rhythm of the brush. During heavy snow storms stores that stayed open were hard to find. A food forager I know of returned to the loft rented for the occasion, a loft devoid of kitchen, stove, hot plate, utensils, plates or can opener, with two dozen eggs and a can of beans. Desperate with rage and hunger and the need to get back to the job, the artists scraped tiles off the bathroom wall, built the tiles into a small oven, set fire to old scripts, heated the beans in the can (which was opened by hammering door keys into it with the edge of a T-square) and fried the eggs on the hot tiles. They used cold tiles for plates.”

Alas, when I finally did reach the point where I was pulling all-nighters, either alone or in a group, there was usually a 24-hour McDonald’s or 7-Eleven within walking distance. Still, it was the spirit of the thing that counted.

—

13. “For, surprisingly, there are old comic book fans. A small army of them. Men in their thirties and early forties wearing school ties and tweeds, teaching in universities, writing ad copy, writing for chic magazines, writing novels—who continue to be addicts, who save old comic books, buy them, trade them, and will, many of them, pay up to fifty dollars for the first issues of Superman or Batman, who publish and mail to each other mimeographed ‘fanzines’ — strange little publications deifying what is looked back on as ‘the golden age of comic books.’ Ruined by (Dr. Frederick) Wertham. Ruined by growing up.”

Well, not all of us…

—

MORE

— RETRO HOT PICKS! On Sale This Week — in 1965! Click here.

— THE SPIRIT AT 85: An Anniversary Tribute to WILL EISNER’S Enduring Legacy. Click here.

—

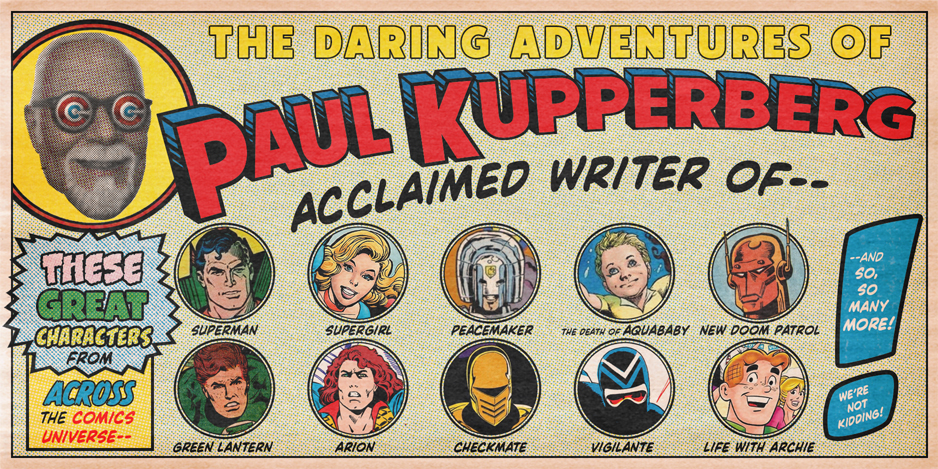

PAUL KUPPERBERG was a Silver Age fan who grew up to become a Bronze Age comic book creator, writer of Superman, the Doom Patrol, and Green Lantern, creator of Arion Lord of Atlantis, Checkmate, and Takion, and slayer of Aquababy, Archie, and Vigilante. He is the Harvey and Eisner Award nominated writer of Archie Comics’ Life with Archie, and his YA novel Kevin was nominated for a GLAAD media award and won a Scribe Award from the IAMTW. Check out his new memoir, Panel by Panel: My Comic Book Life.

Website: https://www.paulkupperberg.net/

Shop: https://www.paulkupperberg.net/shop-1

November 15, 2025

Beautiful!!!

November 15, 2025

I was 10 years old and it was the first hard cover book I had ever purchased. Took me a lot of weekly allowances to afford it at B Dalton’s.

November 15, 2025

My favorite quotes from The Great Comic Book Heroes (I may not have them exactly at this point, but I did read it – many times – 60 years ago now…):

“In America, the opposite of the man who couldn’t get girls wasn’t the man who could, but the man who could if he wanted to but didn’t want to.” Explaining Superman’s odd relationship with Lois Lane, & the standard for ’40s superheroes overall when it came to romance.

Re: Batman, unlike the invulnerable Superman. “Prick him and he bled. Buckets.”

Re: Robin. “Everyone I knew hated him. You could grow up to be Batman. Robin was already better than you.”

Superman & Clark Kent. “[Clark Kent] was Superman’s idea of what we were.”

Feiffer put a lot of my attitudes toward superheroes into my head at a pretty early age. (I think I found the book in my public library when I was 12…)

November 15, 2025

I’ve reread my copy several times. You picked the perfect 13.

Anyone who loves comics needs to read this book.

Also there is no better way to get an understanding of the so called golden age then from someone who was getting these comics off the rack as the targeted audience.

November 15, 2025

Not to edit you, old pal, but it’s worth mentioning that the book existed because Jules was asked to do it by his editor: E.L. Doctrow (later of RAGTIME fame).

November 16, 2025

My gosh! I begged my folks for a copy of this when I stumbled across it in the early Seventies. Read the stories and loved them! Only years later did I read Feiffer’s commentary. Wow!

November 18, 2025

I saw this in the remainder pile at a bookstore in the ’70s and asked my mother to pick it up for me. Still have it, though the dust jacket did not survive over the years.