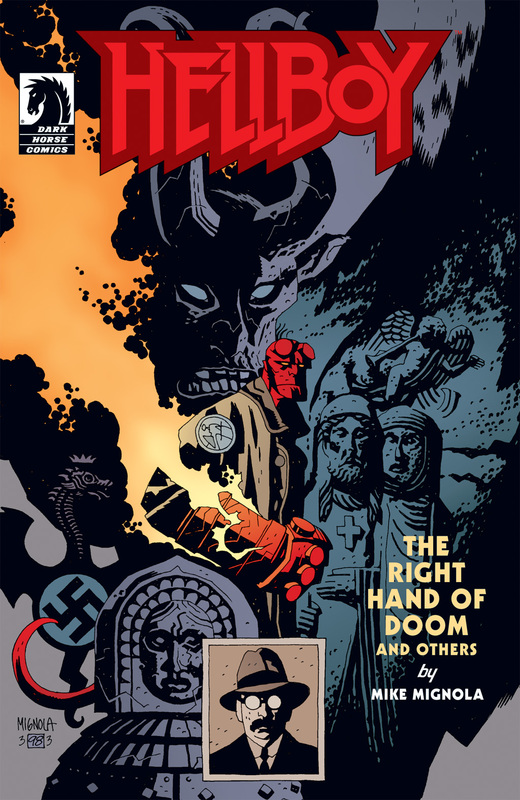

HELLBOY WEEK kicks off in earnest with — who else — Mike Mignola himself. Hellboy’s creator steps into the 13th Dimension for a special two-part MIGHTY Q&A:

Dark Horse has dubbed this Saturday, March 22 as Hellboy Day. If you’re reading this, you’re probably well aware of who Mike Mignola is and how considerable his impact on the comics industry has been. But it’s still an eye-opener to read his official bio:

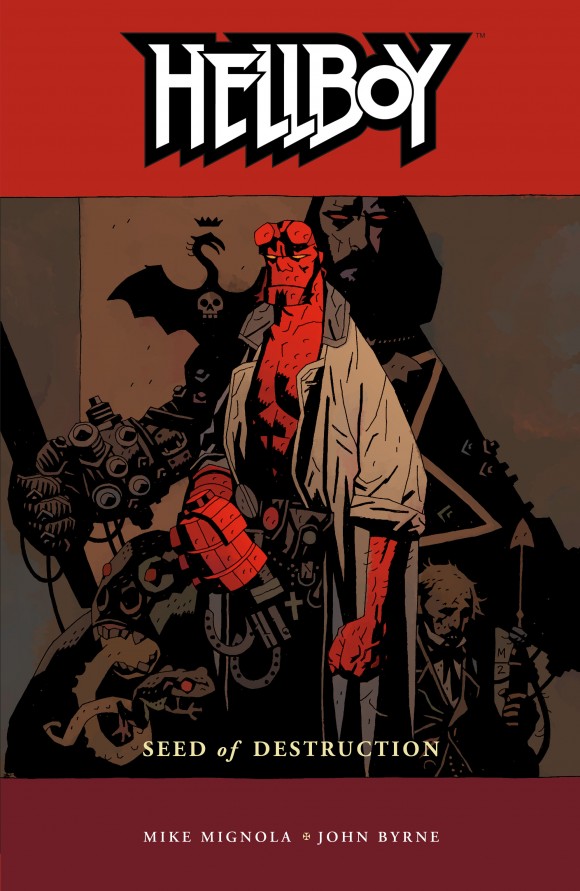

MIKE MIGNOLA’s fascination with ghosts and monsters began at an early age; reading “Dracula” at age 12 introduced him to Victorian literature and folklore, from which he has never recovered. Starting in 1982 as a bad inker for Marvel Comics, he swiftly evolved into a not-so-bad artist. By the late 1980s, he had begun to develop his own unique graphic style, with mainstream projects like DC’s Cosmic Odyssey and Batman: Gotham by Gaslight. In 1994, he published the first Hellboy series through Dark Horse. As of this writing there are 12 Hellboy graphic novels (with more on the way), several spinoff titles (B.P.R.D., Lobster Johnson, Abe Sapien, and Sir Edward Grey: Witchfinder), prose books, animated films, and two live-action films starring Ron Perlman. Along the way he worked on Francis Ford Coppola’s film “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992), was a production designer for Disney’s “Atlantis: The Lost Empire” (2001), and was the visual consultant to director Guillermo del Toro on “Blade II” (2002), “Hellboy” (2004), and “Hellboy II: The Golden Army” (2008). Mike’s books have earned numerous awards and are published in a great many countries. Mike lives somewhere in Southern California with his wife, daughter, and cat.

In this first installment, Mignola and our Clay N. Ferno jump right in and talk about the literary and pulp influences behind everyone’s favorite demon — such as Conan and Solomon Kane.

By CLAY N. FERNO

Clay N. Ferno: Tell us what sort of literary influences come up in Hellboy.

Mike Mignola: It’s funny, I was doing an interview the other day and trying to pin down the roots of the Hellboy stuff — not comic book roots as much as they are pulp magazine roots.

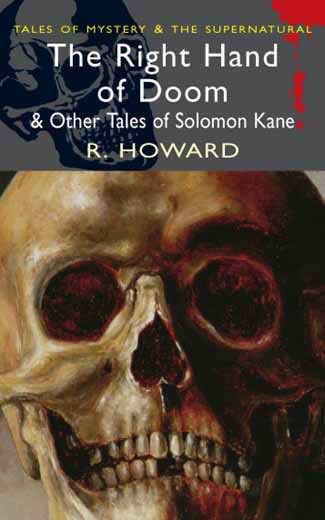

I was listening to the 8 billionth comment about H.P. Lovecraft and I said “Yeah, that stuff is in there, but I think that the bigger, fundamental structure of the Hellboy stuff came from pulp magazine guys like Robert E. Howard and Manly Wade Wellman. Specifically the idea of this kind of character who kind of wanders around and runs into stuff. Also, the short story format, which, at least in most mainstream comics is not the most common way for doing stories, but after the first miniseries, I went quite a bit to doing short stories, and not just short stories, but short stories that don’t take place in a chronological order.

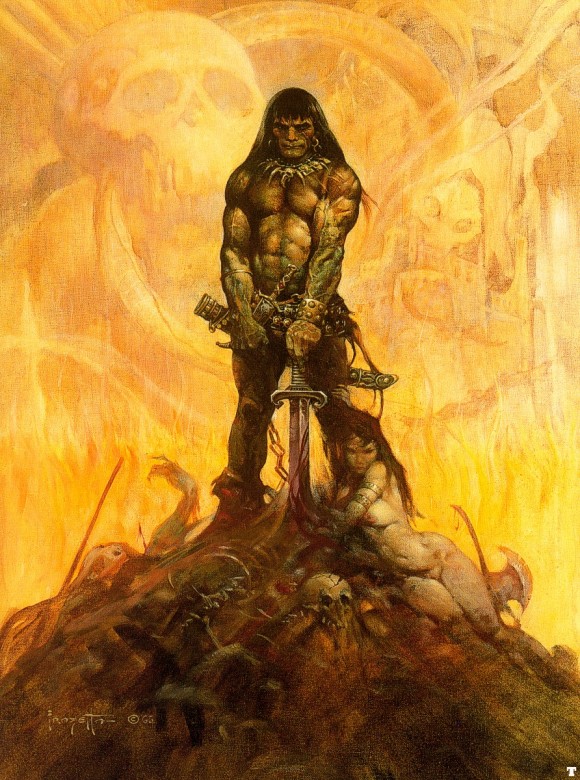

We saw this with Robert E. Howard doing Conan and Solomon Kane and these kind of characters that kind of wander all over the world and they’ll run a story on a character who is old, and then about when he is young, and it is for other people to cobble them all together into some kind of coherent order. I think that was very much informing the way I did Hellboy.

What came along as a surprise — or something that was unconscious, until later — I realized that as Hellboy became a doomed, tragic figure with all of this Beast of the Apocalypse stuff laid on him, I realized I spent almost a year, somewhere in my high school years reading nothing but Michael Moorcock. Everything I could get my hands on by Michael Moorcock.

And I wasn’t consciously trying to put that into Hellboy, but that doomed hero stuff was probably one of the biggest unconscious ‘things’ going into the Hellboy stuff.

That gives me an insight as to how you formed the Hellboy and B.P.R.D. universe. Some people when they talk about your work, that it does come out in short volumes, I guess that is a way of having the reader create the legend in their own mind by stringing it out. What you are saying is that putting out the pieces, not necessarily in chronological order, is kind of the idea.

It is just the way it got done. It is one way to do it when you haven’t figured out the gigantic arc of a character’s life. …

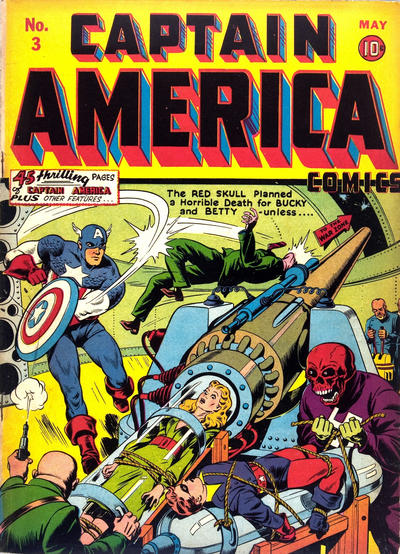

He appeared in the ‘40s so I could link him to World War II-era stuff. My favorite comic stuff had its roots in World War II. Captain America, the Red Skull, that sort of thing. I needed to have Hellboy have one foot in that world.

That first series took place contemporary ’93-’94 so I had a gigantic gap with a 50-year hole to drop stories into.

When I started dropping these stories in there, there was no sense of “here is the arc of his life,” it was just story, almost arbitrarily putting a date on it, somewhere in those 50 years. It was only after doing a dozen or so of these stories, especially when I had to write “The Hellboy Companion”, I would try to make sense of this character’s progress as a life.

It wasn’t purposely something I was doing for the audience’s benefit, and I wasn’t hiding this arc to a character’s life, I simply didn’t know it.

To jump back a bit — you brought up Lovecraft, would you say he was more of an artistic influence because you wanted to draw cool supernatural monsters, rather than a writing influence?

What Lovecraft did, and there were several guys before Lovecraft, like William Hope Hodgson and other pulp magazine guys that were writing contemporary with Lovecraft that have this idea of a “cosmic horror.” This big un-knowable universe, as opposed to vampires and werewolves and stuff like that, ghost stories — I love that stuff. In creating this universe, I wanted that bigger cosmic presence there. Lovecraft and those kind of guys were definitely a conscious influence to get that big cosmic “thing.”

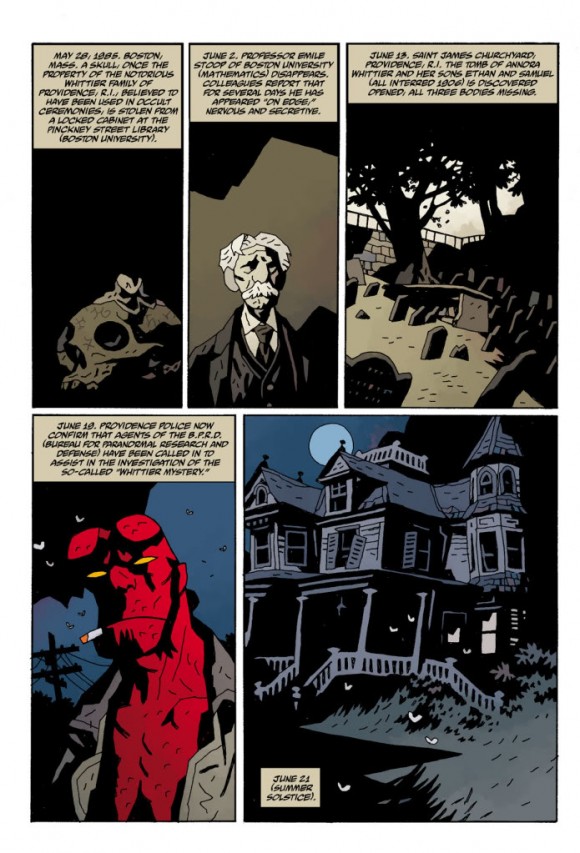

One thing that I’ve been really careful of is not doing Lovecraft. There was one story I did where I tried to do a conscious nod to Lovecraft, a real short thing called “The Whittier Legacy.” That’s a sort of Lovecraft-sounding title. As much as I love that stuff, I wanted to make my own mythology, my own cosmic thing, inspired by him, but it wasn’t like I was going to reference Cthulu and those guys.

If we think about comics for a second, the large-scale cosmic, everyone obviously thinks of Kirby and all of the stuff you probably grew up on, and there are people like Wally Wood, when people are coming into their own as comic fans or artists, are digging deep and going back in time for reference and who the masters are. Are there any artists from the past that aren’t getting enough attention?

I’m sure there are … but it is tough for me because I have my stuff. I have my books on my shelves. To me, a guy like Wally Wood, I’m not aware that he doesn’t get a lot of attention. Probably for young people, he doesn’t. But to me, I have a couple of Wally Wood art books. To me and the people in my circle, Wally Wood is very revered. Jeff Jones is revered, Frazetta, certainly.

What is scary is when you talk to young people out there, these guys are off the map. When I was a kid, and this applies to movies and everything else, there was so little of this stuff that you weren’t bombarded with everything, you didn’t have the Internet. If you were into monsters or comics, you had to seek these guys out.

My generation is a little more aware of comics history. First off, we were closer to the history of comics and I was reading this stuff in the ’70s, and even in the ’60s. Marvel Comics was new, the world of comics was much fresher. The stuff that I’m familiar with, I don’t realize kids aren’t familiar with it.

I did a show, HeroesCon, a few years ago, the year after Frazetta died, and an artist came up to me, a young guy. He was asking about composition in my work, and I made some reference to Frazetta and all my compositional stuff comes from Frazetta, and he didn’t know who that was. It was so grim and at the same time, eye opening.

It is spooky to see certain guys that to me, were the biggest guys kind of fading out.

To go back to the original question here, as far as guys who are my “biggest” guys — Kirby who still gets a lot of attention, but he has become a historical figure. To me, when I was reading comics, he was still working and he had left Marvel when I was really into Marvel Comics, but he hadn’t been gone that long. Marvel was reprinting his stuff and I was buying back issues. Still, the defining guy at Marvel was still Kirby. The stuff that Kirby and Stan (Lee) did, that’s still comics to me. That is many years in the past to a young artist.

That’s why I try not to think about it — it can be depressing! I hear guys say that they grew up reading my stuff, and I say, “Whoa, you couldn’t have done better than that?” (Laughs.)

And guys credit me for my unique style, because I use a lot of shadow and things like that, but dude, look at Bernie Wrightson, look at Mike Kaluta. Look at that generation of guys coming out of that older tradition of comics — this is where I got that stuff. Frazetta. But guys talk about me like I invented this stuff.

My first introduction to your stuff was the Batman “A Death in the Family” covers, X-Men Classic covers, Wolverine covers. I was thinking, “I want to draw like THAT.” That’s different, and I had no idea of what came before you.

When I was working in mainstream comics, almost in the very beginning, I wasn’t looking at the other guys that were the hot guys or styles at the time. My roots were so much in the older guys, not just comics people but painters and illustrators. I just brought that to comics. I knew Art Adams. I certainly wasn’t trying to be Art Adams. That wasn’t my kind of thing, and that’s because I wasn’t looking at comic book artists, I was looking at other kinds of artists.

Tomorrow: Mike Mignola meets his heroes.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks