The artist on the new Hellboy graphic novel talks art and artistic inspiration.

—

Mike Mignola sure can pick ’em. The creator of Hellboy has, unsurprisingly, a great track record of picking collaborators for his signature character. The latest is illustrator Gary Gianni, the artist on the new graphic novel Hellboy: Into the Silent Sea, out now from Dark Horse.

Gianni spoke at length with 13th Dimension contributor G.D. Kennedy about the project; working with Mignola — and others like George R.R. Martin and Ray Bradbury; the artists who influenced him; and, the nuances of theme in storytelling.

Gianni, it’s worth noting, will be featured as a special guest at the prestigious Spectrum Fantastic Art Live show in Kansas City this weekend. There will be a panel discussion Friday at 3 p.m. on Hellboy: Into the Silent Sea, followed by an autograph session. Details here. — Dan

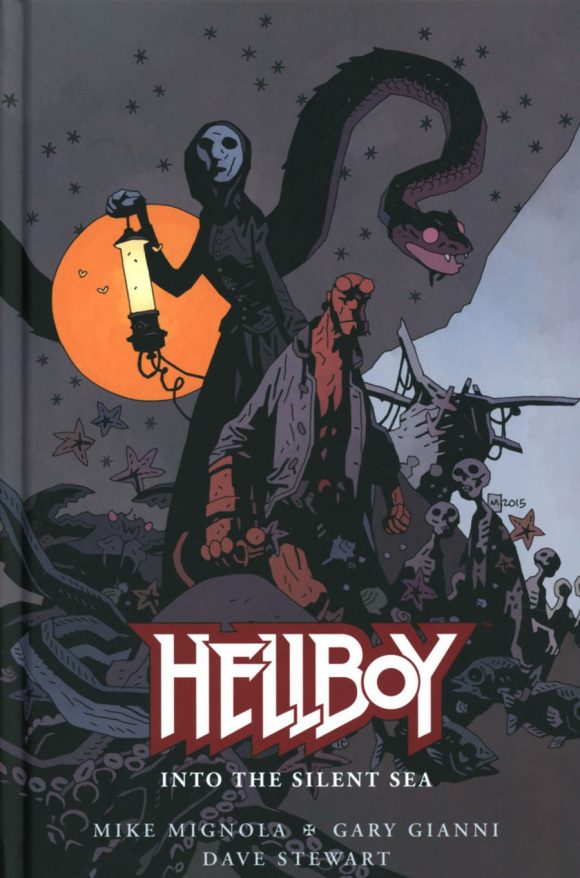

Cover line art by Mignola

—

By G.D. KENNEDY

Mike Mignola spent the last two decades telling Hellboy’s story, weaving a tale across some 60-plus years from the character’s “birth” in World War II, to his ostensible end in last year’s (really fantastic) Hellboy in Hell. The result is that even after all of the Hellboy stories to date, there are a lot more to tell, and many gaps in Hellboy’s history left to be filled. Mignola has slowly been doing this in recent years, with B.P.R.D. mini-series so far highlighting Hellboy’s adventures in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Hellboy: Into the Silent Sea is another one of those gap-filling stories, fitting chronologically into the main Hellboy narrative around the time that Hellboy began his journey home after years lost at sea. However, while it is very much a critical piece of Hellboy’s history, Into the Silent Sea works impeccably as a standalone graphic novel, a self-contained story about hubris and the seafaring life, thriving on an aesthetic leaning heavily on 19th century Gothic literature, with a hint of Lovecraft-ian horror thrown into the mix.

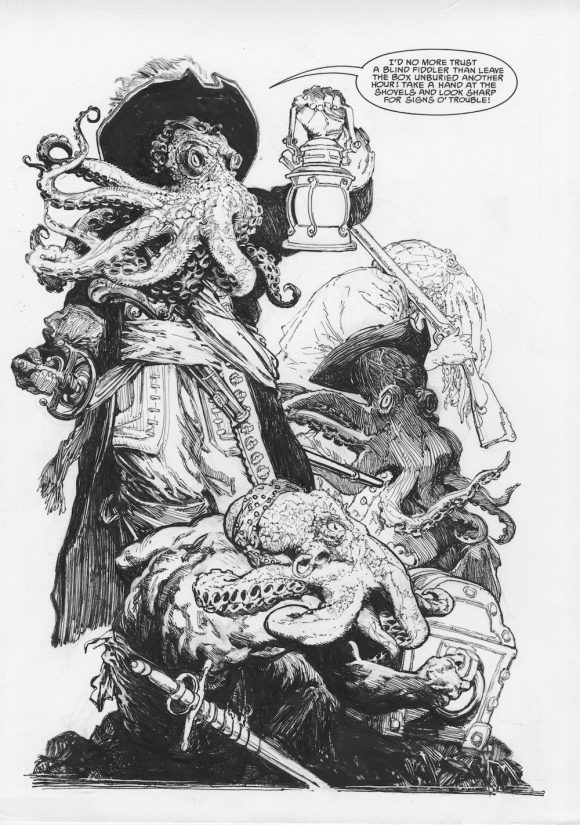

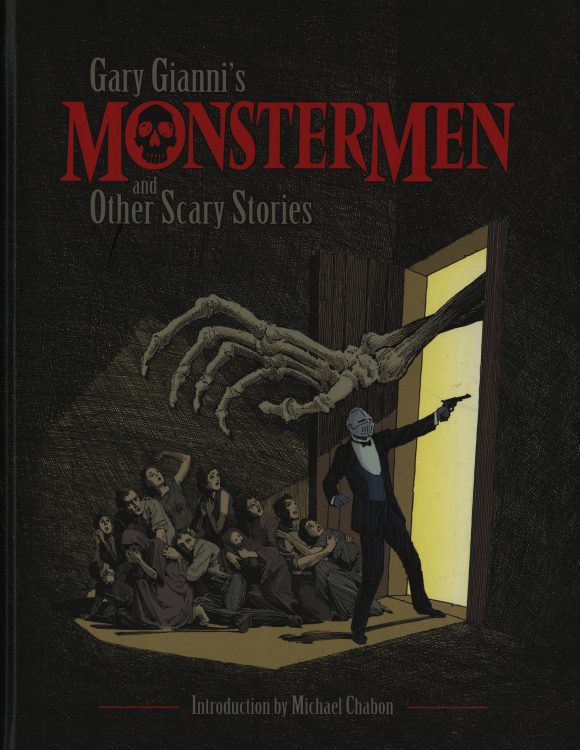

However, for as much credit as Mignola deserves for this book, it would be nothing without the work of Gary Gianni, who co-wrote it and also is responsible for its stunning artwork. For the uninitiated, Gianni is an incredibly talented artist who utilizes classical flourishes that immediately conjure Bernie Wrightson and many great pre-Code horror comic artists, playing in a heavy and liberal line work, with an eeriness always creeping in at the edges. Gianni is, in many ways, an enigma in comics: He is an amazing talent (and even nicer person) and has a handful of titles to his name—astute Hellboy readers may recall his MonsterMen back-up stories, and he worked on the Prince Valiant newspaper strip for years—but he has been equally, if not more successful in other ventures, maybe most notably in illustrating books, having worked with the likes of Ray Bradbury and George R.R. Martin.

With Into the Silent Sea, out this week, Gary took the time to speak with us about his new graphic novel, working with his longtime friend Mignola, and Hellboy.

—

G.D. Kennedy: How did Hellboy: Into the Silent Sea come about in the first place?

Gary Gianni: I’ve known Mike [Mignola] for a long time – 22, 23 years now – just when he was first starting out on Hellboy, and it wasn’t too long after that we found we really hit it off, and he asked me if I would be interested in doing a back-up feature to Hellboy. I was delighted to be invited to do that, because he gave me a blank check to come up with whatever I wanted, which was a little daunting at first. But I worked out a comic character – an idea that I had in the back of my head for some time, called the MonsterMen stories, and over the next couple of years, I would provide him occasionally with backup stories for his comics.

We talk occasionally and we’re on the same page as far as books and films and even our senses of humor seem to be running along the same lines, so he knew what he was getting when he invited me in, that’s for sure.

G.D.: The new book is something that you co-wrote with Mike, in addition to you doing the art. How did that play out in practice, given that Mike has such a deep investment in this universe?

Gary: That’s a good question, and once you get into the creative process, it’s fairly involved. It was something that I was worried about because it is Mike’s baby, and he has had other artists work on the stuff, but to my knowledge, I’m not sure quite how much input they had on the story. But he had Hellboy refer to a little side adventure where he was lost at sea [Hellboy: The Storm #1], and Mike bookmarked that years ago as something that he thought, “I’m going to try and get Gary to draw some day.” At least that’s what he told me.

So it was a few years down the line and I finally had a window of opportunity, and I said, “OK, let’s try this,” although I was nervous about it, because my style is so different from Mike’s, and I’m not very good at switching styles or trying to copy someone. He said, “Don’t give that a second thought. I want what you do. I want what you’ll bring to this thing.” And I said, “Well, I’m worried I’m going to screw up Hellboy,” and he said, “Oh, no, don’t worry about it. If anybody screws up Hellboy, it will be me.” He said, “I’ll by disappointed if you don’t give me Gary Gianni.”

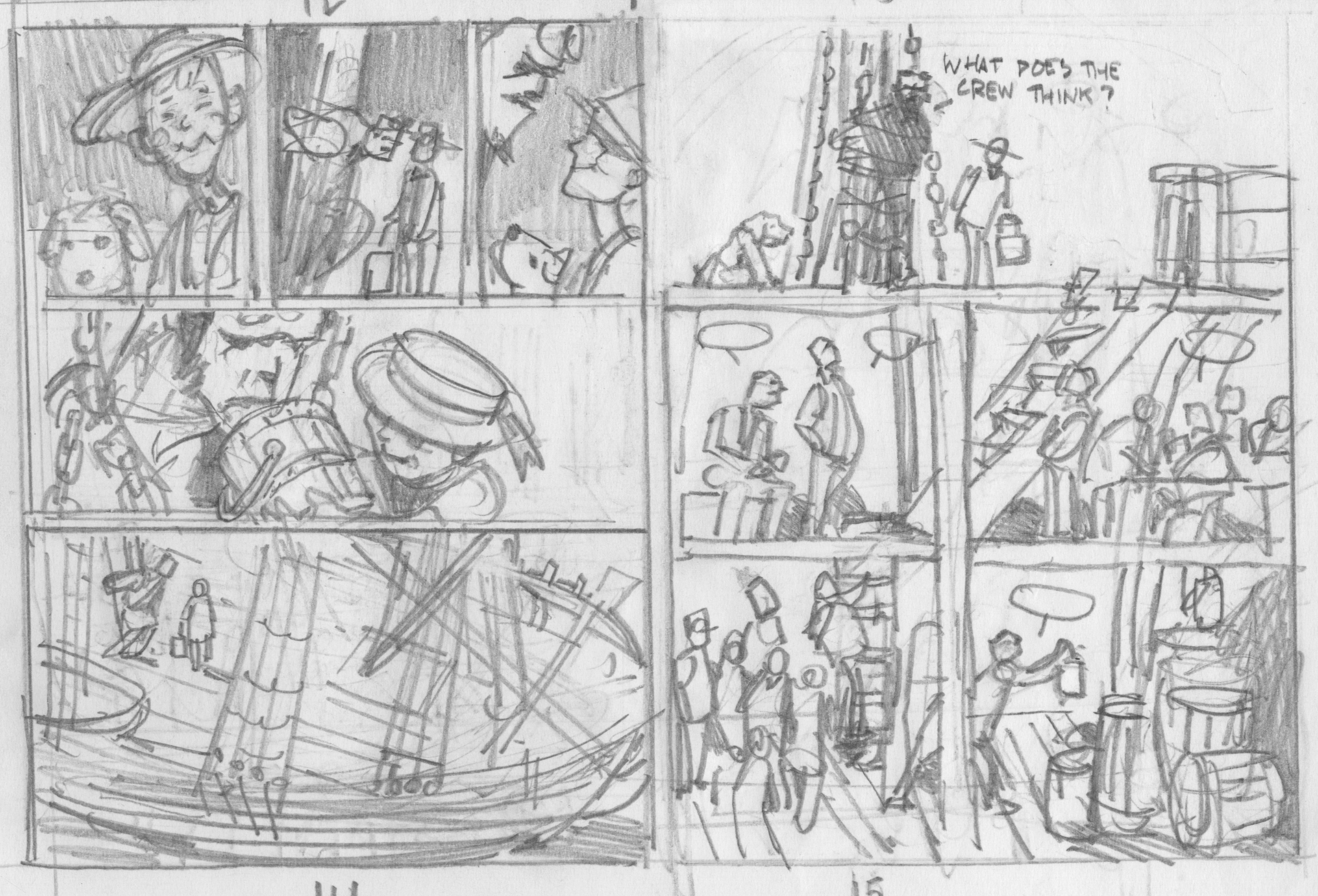

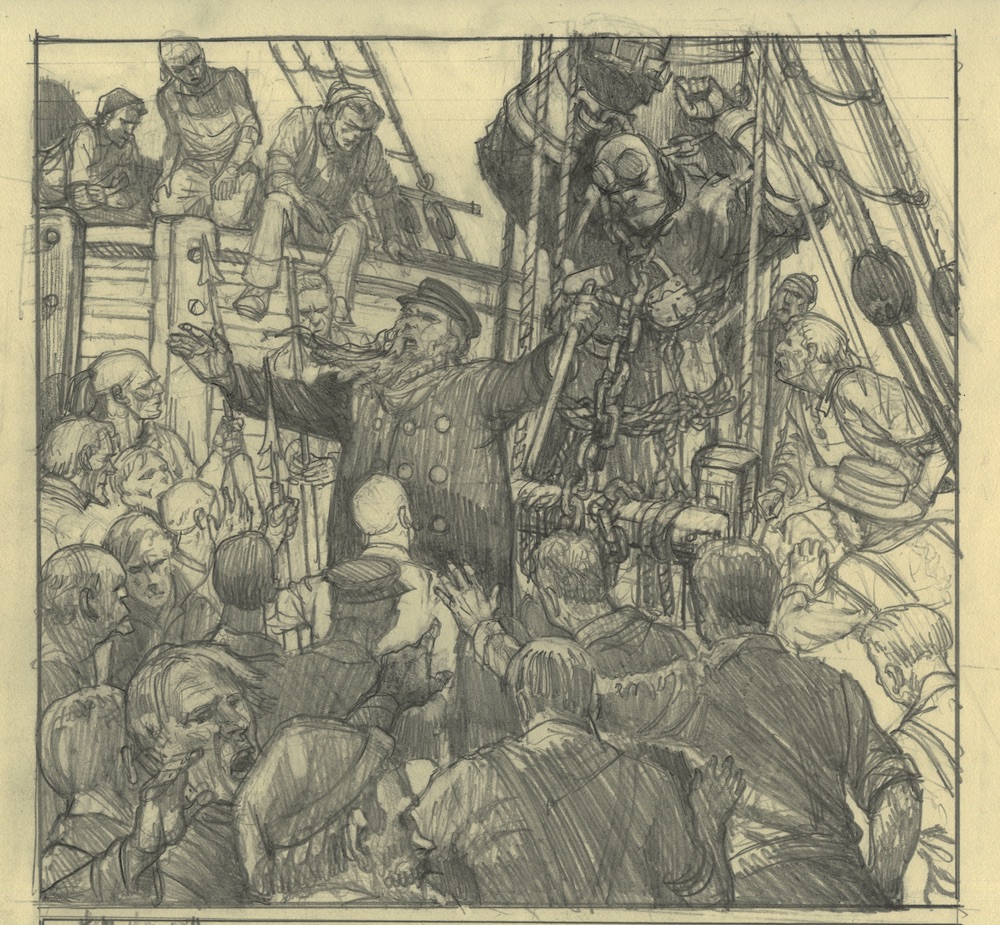

And so, with that in mind, it was a lot easier to move forward on it, and he did provide me with a rough outline of the thing. He also included a lot of things that he knew I’d like to draw, and I was able to flesh that out – we went back and forth and we talked about it, until finally I just started working on it. I showed him pencils as I went along. I did roughs – little thumbnails – and then we tweaked those, some of the storytelling and visuals were altered.

By and large, it was a pretty smooth operation. I was surprised to see that. I’m sure you have friends who if you work with them, you’re not sure if it’s going to ruin your friendship somehow, because it’s a different beast, working with someone professionally, and being a friend of theirs. Especially something that’s so important to Mike. There’s a certain amount of trust – a give and take – especially on his end that I’ll do the right thing, and on my end, to be able to say, “Yes, maybe you’re right, I’ll change this.” There wasn’t anything I did that was written in stone, and I’m sure that it was a very elastic relationship we had.

Now that I look at it, I’m sure even a diehard fan would have trouble saying where Mignola ends and Gianni begins, and Mike said this himself. I’m delighted with the results.

G.D.: The narration and cadence of the project seems to fit naturally with so many of Mike’s other books. So much of the pacing is art-driven, and light on narration. How was the process for you, driving the story so much through just the art?

Gary: I think the main thing is mini-movies. There is a pacing and a certain amount of up and down connected with it, where you want the reader to be manipulated by the flow of this thing. Hopefully, if you do it right, it’s like any other storytelling narrative – you just have this intuitive thing going on that’s hard to explain. This isn’t the greatest answer in the world. I don’t know how else to explain the process.

G.D.: I’m always fascinated by the interactive process between the writer and artist.

Gary: Well, I think arguably the best comics are probably written and drawn by its creators. It’s not true in every case, but you’re dealing with two different disciplines, writing and drawing, and these two things have to be integrated where there’s a great deal of editing going on. Unless you have the two people who are really working on the same plane, it’s difficult to do.

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby are examples of two creators who pulled that off very well, in a very integrated fashion. And I suppose I would describe Mike’s and my effort here as something along the lines of what Stan Lee and Jack Kirby did.

But I’m also interested in the creative process. I’m trying to verbalize that as well as I can. It’s something that – between an artist and a writer, you almost need Mr. Spock’s Vulcan mind meld, kind of touch the other guy’s head to get a sense of what the two of you are doing. It is difficult to explain, but you are right, it is a fascinating process.

It’s funny when you think, that one I did, took me maybe 10 months, maybe even a little longer to do, and someone can typically read it in about 10 or 15 minutes. Funny how time really is relative.

G.D.: If you aggregate the time that everyone takes to read it, I’m sure it would add up to your 10 months somehow.

Gary: I didn’t think of it that way.

G.D.: You reminded me – when you wrote this, you dedicated this to Mr. Kirby. Is there any reason for that in particular?

Gary: Well, I grew up reading Kirby’s comics. When I was a really little kid, I was a poor reader. Through the medium of comics, I sort of learned how to read, and actually enjoy reading. It was the integration of words and pictures in this visual storytelling fashion that helped me with that.

I remember I used to go to this drug store when I was a little kid where they used to have all of these comics set up. I knew the owner of the store, and every week he’d let me set up the comics on the rack, and he’d give me one. I was probably about five or six years old when I was doing this. And I’d sit on one of those swivelly stools and drink a Coca-Cola and read the Hulk or Spider-Man. These are the kinds of things that made a big impression on me as a little kid.

So, someone like Kirby, or Steve Ditko for that matter, those guys are part of my DNA now. In spite of all of the art training I’ve had and the art history class and 500 years of art history, these guys working in pop culture still mean a lot to me. That’s Kirby.

G.D.: You mention your extensive art training. As I look at your style, it’s often reminiscent of Bernie Wrightson, while at other times it invokes an old wood carving. Some of it is similar to the art in Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

Gary: I am aware of that stuff, and you name a lot of references that I run parallel with, everyone from Gustav Dore to Bernie Wrightson, of course. They’re all there. I’m not consciously aware of that stuff while I’m working. It’s all floating around in there.

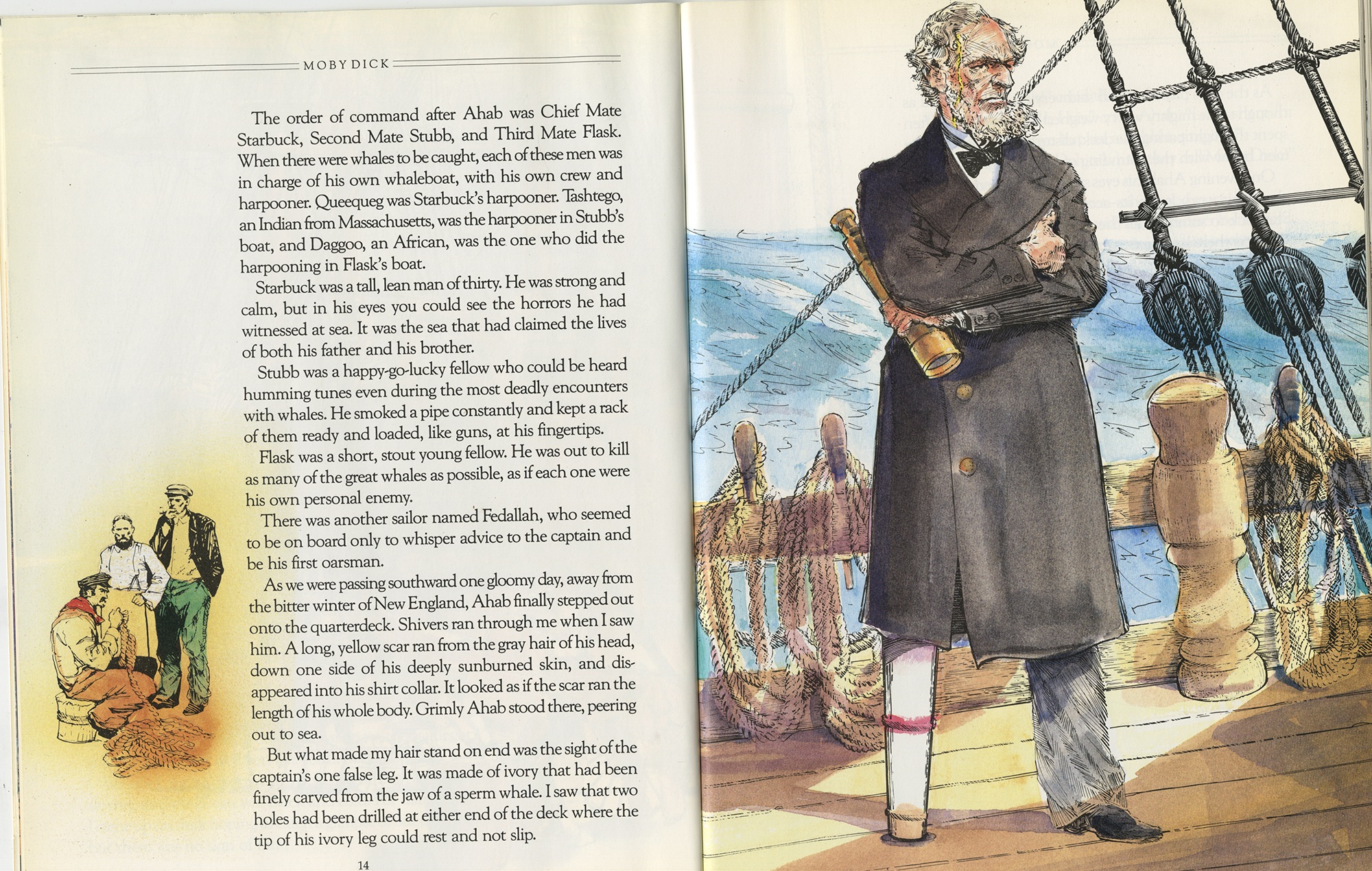

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by Gustav Dore, of course I pulled those out because Mike and I were riffing on that as much as we were Moby Dick. So yes, there is all of that thrown into the stew – not only the visual element, but the literary references as well.

They all go in a pot and are stirred around, and hopefully – of course it’s a pastiche of a number of things – but you’d like to think that maybe at the end of the day, you’ve created something a little new, that has some resonance here in the 21st century, and we’re not just thought of as people who are ripping off everything from the 19th and early 20th century.

G.D.: Another element I find interesting is this theme that runs through so much of Hellboy, and is consistent with Moby Dick as well, is this idea that infinite knowledge acquired through shortcuts is dangerous.

Gary: Well, it certainly is a trope that goes all the way back to Prometheus. And of course Frankenstein, and countless science-fiction films and cautionary tales. By the end, I was referencing the 1950s movie, Howard Hawks’ The Thing, where the scientists are trying to talk with the alien there.

But yeah, all of those tropes, along with things like phantom freighters and ships that you’d see in much of the classical literature of the day – the Flying Dutchman and the Mary Celeste – all of these things are there for anyone who wants to look at the subtext. But at the end of the day, we’re just trying to entertain people. We’re hoping that people have fun with it and find the humor in it.

As a matter of fact, I would say that is one of the prime ingredients in Hellboy is the whimsy of the character, as much as it is a horror comic. I’m not even sure “horror” is an apt description; if anything, the Hellboy stuff comes off more as Romantic heroism, with Gothic connections, and even up into the 1930s with the pulp detective, the hard-drinking, forlorn detective in the trench coat, with the empty booze bottle. All of that stuff is there, and it’s nicely brought together in a way that you can find whatever you want in there.

Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

G.D. I’ve always been of the view that themes and metaphors develop themselves, and I always find it interesting to talk to writers and artists who, often, will say that they never thought about that, or that wasn’t intended.

Gary: Your notion that themes develop themselves – there’s so much truth to that. And when you turn around and ask an author or an artist about their work, they may be inclined to say that. I’ll have to remember that, because the next time somebody asks me about the creative process, I’m just going to say, “They develop themselves.” Unfortunately, most listeners or readers won’t find that very satisfying, but that is the answer

It reminds me of a question that a lot of young artists ask me at conventions. They will come up to me and they always want to show me their work, and I’m always happy to look at it. But I’ll say, “This is very good and keep it up. Don’t get discouraged,” and two or three other things that sound pretty cliché, but are universally true. And they will say, “How did you get to where you are?” That’s the wrong question, because times are different, they are not me, and their opportunities are going to be totally different.

Again, I can only resort to the clichés: Be open to opportunities. Try not to be disillusioned by any setbacks. Stuff like that. At the end of the day, they are always disappointed that I don’t have something that they can hang their hat on. They are looking for something a little more tangible, like this great epiphany is going to happen while we’re both standing on the convention floor.

G.D.: If you draw your eyes a quarter inch farther apart, that will solve everything.

Gary: [Laughs] Yeah, you got it. What we’re talking about is extremely interesting. As much as anything that we’ve said so far. It’s a very mysterious thing that we stuttering over here, and hopefully people might glean some insight.

G.D.: When I look at your work, it is so distinctive. You use lines so liberally at times. It creates a very unique style. Do you think that this is something that allows you to stand out from the crowd a bit?

Gary: I see what you’re getting at. This is something that just comes naturally to me, or Mike, or any other artist. You walk down any artists alley in a convention and you see myriad styles and approaches, and this is what confuses a beginner, because you have all of this stuff thrown at you.

All I can add to that is that at the end of the day, you may love 15 or 20 different ways of working and can be seduced by all of this different work, but if a genie came down and said, “What would you really like your work to look like?”, well, now that’s the $64,000 question. The best answer is that you have to be honest with yourself. You have to evolve somewhat to the point where you say, “I like these 10 different guys, but this is not what I really want to do.”

That again is an answer that is not exactly the most satisfying reply, but it is an honest one. I didn’t consciously go out of my way to be different from Mike Mignola or any other artist; it’s like spring turning into summer – I don’t know how it happens, but I know what I feel naturally comfortable with. These are hard lessons to learn, and they are not learned overnight.

I’m 62 years old and I still feel as if there’s a lot to learn here. I’m happy to watch the evolution of all of us as creators.

G.D.: You’ve had a long and winding career, from being a courtroom reporter, to doing the Prince Valiant series, to illustrating books, but no comics in a long time.

Gary: I haven’t done a comic in years, and I realized why – they are hard to do. They are very difficult, and that’s why I take my hat off to anybody who puts out a monthly comic. It’s a lot of work, and it’s something that I’m not sure how many more I can do myself.

G.D.: What is so challenging about comics?

Gary: It’s hard to say where that goes. Maybe it’s that I don’t have any formula for comics since I do them on such an odd time frame, I’ve never developed a way of working that I’ve felt comfortable with. Every time I do one, it seems as if I’m starting from scratch, and every artistic gear in my head is rusty. So, maybe that has something to do with it.

I also am interested in so many different forms of visual storytelling that I’ve found that I don’t really mind the checkered background that I have, and I really do enjoy book illustrations as well.

It’s a great time to be involved in and an observer of this whole media scene and pop culture, especially with the changing paradigm and print becoming something that is fighting for its survival with other forms of entertainment and storytelling.

I was just getting on a plane to go to a paperback and vintage book show in L.A. a couple of weeks ago. And of course the plane was delayed and I was at the gate with 50 other people and I was reading a book. At some point I looked around, and every one of those people was on their iPhones or some sort of electronic medium. I could see the irony – here I am, going to a paperback show, and there is no one with any scrap of paper on them. It’s interesting to see these shifts. I’m not sure where it will go, but it is exciting.

I’m always interested in different ways a writer can pull you into a narrative in an unconventional manner. I just finished reading George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo, which I thought had this terrific sort of way of jumping back and forth between characters and newspapers – actually, non-fiction reports from the newspapers and diaries from the times of Lincoln’s presidency. It’s a fantasy novel, actually, based on an actual incident – Lincoln’s son died during his presidency and one night, he went and visited the crypt by himself and was in there all night. This was reported by some of the gatekeepers of the cemetery at the time.

But George Saunders read this account and he developed a story around it that deals with all of these spirits that are not at rest and are floating around the cemetery, still connected to the planet for one reason or another, and they’re watching this relationship between Lincoln and his dead son unfold. It’s a brilliant fantasy novel, and yet it was very poignant and worked on many levels. The thing that struck me about it was the way that it unfolded.

G.D.: You’ve worked some fantastic authors – Ray Bradbury, George R.R. Martin, and others. It’s an amazing list of authors.

Gary: It really is. I feel very fortunate that it’s worked out this way. Every one of those authors, they’ve allowed me personally to play around with their material – I can’t believe my fortune on that – and I count all those guys as friends. Michael Chabon and George R.R. Martin, Ray Bradbury and there are a couple of other people – even Archie Goodwin, who is often overlooked these days, he was a writer working on Creepy and Eerie magazines when I was a kid, and to think that, flash forward 20 or 30 years, I’d be working with him on a comic, talking about how to construct the story – I’ve been pretty lucky.

G.D.: What comes next?

Gary: I have something I’m working on that I can’t talk about, which unfortunately makes people want to know more about it. What is it that Sherlock Holmes says? “The facts regarding this case, the public isn’t ready for them.” It’s a book project.

There are a couple of things that I am excited about, though. There are some collections of my work that will be coming out very soon. Dark Horse is re-releasing all of the MonsterMen stories this summer in a collection, so that’s something I’m happy to see coming out. If you like the work I did on Hellboy, you may enjoy these stories as well.

Also, the eight-year run I did on Prince Valiant for the newspapers – all 450 of those newspaper strips – are being collected into one book. Flesk Publications will be putting out the Prince Valiant collection in early fall.

G.D.: Any more Hellboy?

Gary: People have asked me if I’m going to work on anymore Hellboy, and I have to admit that I’m afraid to say that as much fun as this was, it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I gave it everything I have, and I’m very proud of it. It’s a standalone thing – I think even a casual reader would enjoy this. I’d love to work with Mike again on something else at some time, and there’s always that possibility in the future. But this was my one stab at the great occult detective Hellboy.

April 20, 2017

Great interview. Thanks, Dan.