A talk with Eisner’s former publisher.

—

UPDATED 3/17: Will Eisner would have been 100 on March 6. We’ve gathered our best Eisner coverage and are re-presenting it for the occasion. For a complete index of stories, including contributions by Darwyn Cooke, Matt Wagner and Francesco Francavilla, click here. Enjoy.

—

By CLIFF GALBRAITH

When we decided to do a WILL EISNER WEEK here in the 13th Dimension, Denis Kitchen was the first person I contacted. He told me a great story about meeting him and how the underground comix movement influenced the venerable artist…

Cliff: Will did so many things, it’s hard to pin down one aspect of his career, his contributions, but I’d like to get your thoughts on one oh them. You worked with him, published or republished a lot of his work — do you have one story about the time you spent with him?

Denis: That’s a loaded question, Cliff. I could go down a lot of avenues here, especially since we’re in the 13th Dimension, but here’s something that some of your readers might appreciate. Keep in mind that I wasn’t shy when I started in cartooning in publishing. I reached out to Stan Lee, to Harvey Kurtzman, and others who should have intimidated me as a skinny kid still green behind the ears. But Will Eisner, rather astonishingly, sought me out. I never fail to be impressed with that very first meeting, back in 1971, at a Phil Seuling convention in New York.

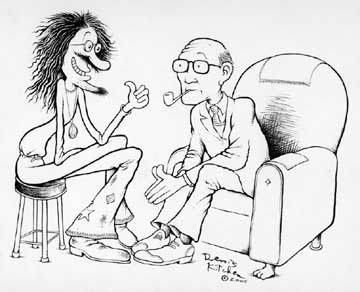

Long after Eisner was already a legend in comics for creating The Spirit and inventing much of the vocabulary of comics, and long after pioneering educational comics for the army and private industry, while also being a successful businessman, he found me through an intermediary and said he needed to ask me some questions. “Me?” I was sure there was some mistake. For full context, you have to picture the scene. Will was in his mid-50s and balding. He was a button down guy —a literal suit and vest and tie guy.

The closest thing I had to his tie was that my pants were tie-dyed. I had long hippie hair, a scruffy beard, and was more than thirty years Will’s junior. The two of us were a picture of the generation gap. And I was not just a young cartoonist and publisher; I was an underground cartoonist and publisher. As Will noted years later, “We both smoked pipes, but with different substances.”

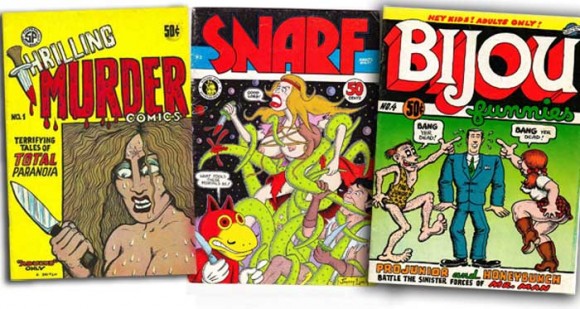

The “underground comix” I was publishing and sometimes drawing were about drugs and sex and the Vietnam War and gender politics and angst. They were often full of graphic violence and acid trip imagery and the not infrequent depiction of genitals. They were my cartoonist generation’s reaction against Frederic Wertham and the hated Comic Code Authority and straight society and middle class values and all that was flawed or hypocritical in our culture. Our audience was other hip, tuned-in, radical longhairs and stoners. In short, we expected anyone balding and 50-something to be downright appalled by our comix. Instead the living legend Will Eisner sought me out.

He wanted to talk at that early convention because he was then, and remained his entire life, an intensely curious man who deeply loved the comics medium, who saw a still untapped potential, and was always looking for fresh perspectives and better mousetraps. He had vaguely heard —probably from Seuling— that underground cartoonists owned their own copyrights and trademarks, kept their own original art, had little or no editorial restrictions, and —for the businessman in Will, this was the most intriguing element— that we sold our comix on a non-returnable basis, and to non-traditional venues. And certain publishers, like myself, encouraged and instigated these practices, unheard of during his comics career. As we talked in a private room in the convention hotel, I confirmed one-by-one the things that made him curious about this noisy new development in comic books. I did my best to squeeze in my own questions about “the old days” and The Spirit, but he was sparse in those details; he was there to learn about new directions, not to reminisce.

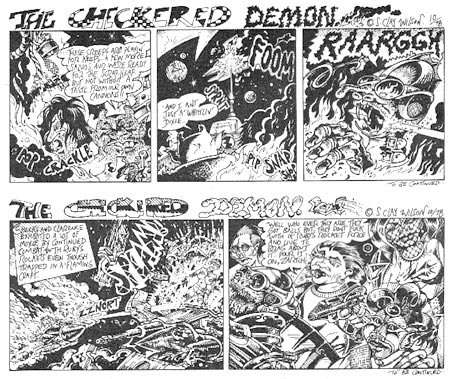

Will not only showed remarkable curiosity about what a new generation of cartoonists were doing, but he went well beyond that. And that’s what sticks in my mind to this day. Yes, initially he did express generational shock at some of the actual content in undergrounds: a particular S. Clay Wilson image almost fatally jettisoned our burgeoning relationship.

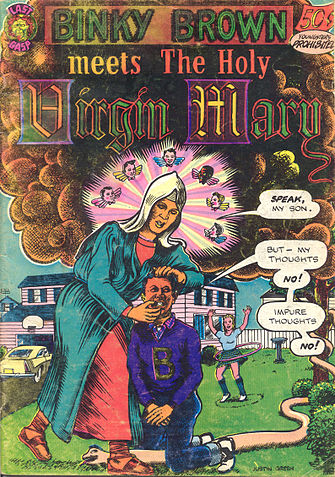

But once he accustomed himself to our rough creative edges, he began to appreciate the voices and images and ideas springing from the undergrounds. The ultimate thing that, I think, defined Will as an unusually open man and artist, is that he allowed himself to be influenced by the work of younger artists. He especially appreciated creators like Justin Green, whose Binky Brown Meets the Virgin Mary, was a painfully revealing cartoon diary, and the first really autobiographical comic book; Jack Jackson’s insightful historical comics about Texas in the 1800s; and Jim Vance and Dan Burr’s Kings in Disguise, among others.

In 1978 Will Eisner padded his already impressive career résumé with A Contract with God, the book that literally started the graphic novel revolution. In that groundbreaking work he incorporated both overt and subtle autobiographical elements, along with scenes that were risqué for the day and some than remain eyebrow raising. Afterward, in interviews and talks, he openly acknowledged the influences from underground comix. There are few established masters in any creative field who will both take the time to examine, and look with an open mind, at the work of young upstarts, then allow such material to impact their own work, and then publicly admit the debt. It takes a self assured and wise man, two of many qualities I admired about Will Eisner.

Denis Kitchen is an artist, publisher, agent, curator, and founder of Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks