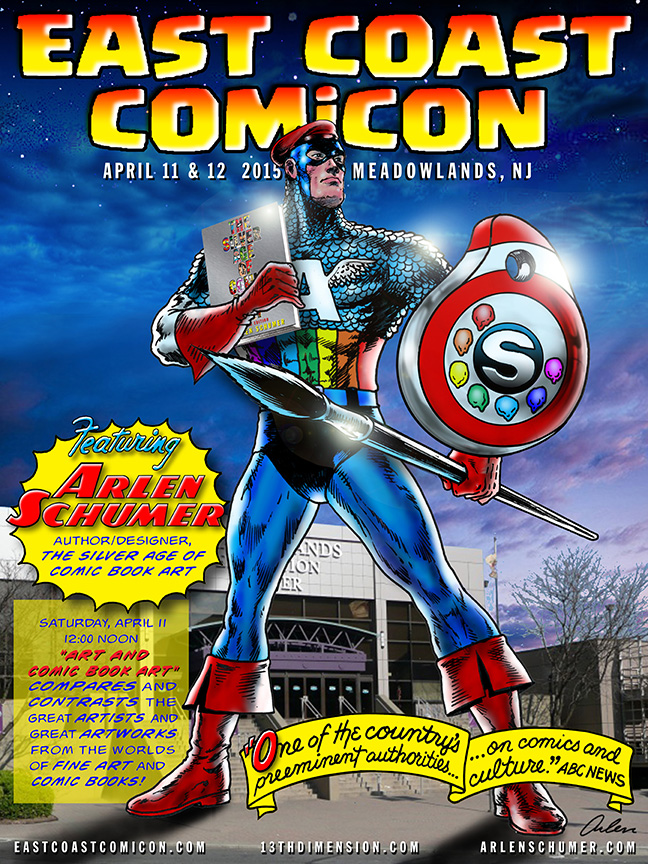

PART 3 OF A THREE-PART SERIES: Comics are wonderful. But are they fine art? Just ask historian Arlen Schumer.

Arlen Schumer will be speaking at EAST COAST COMICON — which 13th Dimension is sponsoring – and here’s a preview of his lecture, excerpted from his verbal/visual essay slated to appear later this year in the British hardcover anthology A-1.

In addition, both Neal Adams and Jim Steranko — whom Arlen writes about here — will also be at the show!

Part 1 can be found here. Part 2 can be found here.

—

BY ARLEN SCHUMER

If the human figure is the foundation of comic book drawing—indeed, of all drawing–then its epiphany is found in the distinctive, dynamic style of Gil Kane (1926-2000), one that matured demonstrably during lengthy runs on a pair of DC Silver Age superheroes, Green Lantern and the Atom. Kane’s figurework was both a primer on structural anatomy and musculature, and a lifelong quest to bring his characters to life, by endowing them with all the grace and lyricism his drawing prowess could muster.

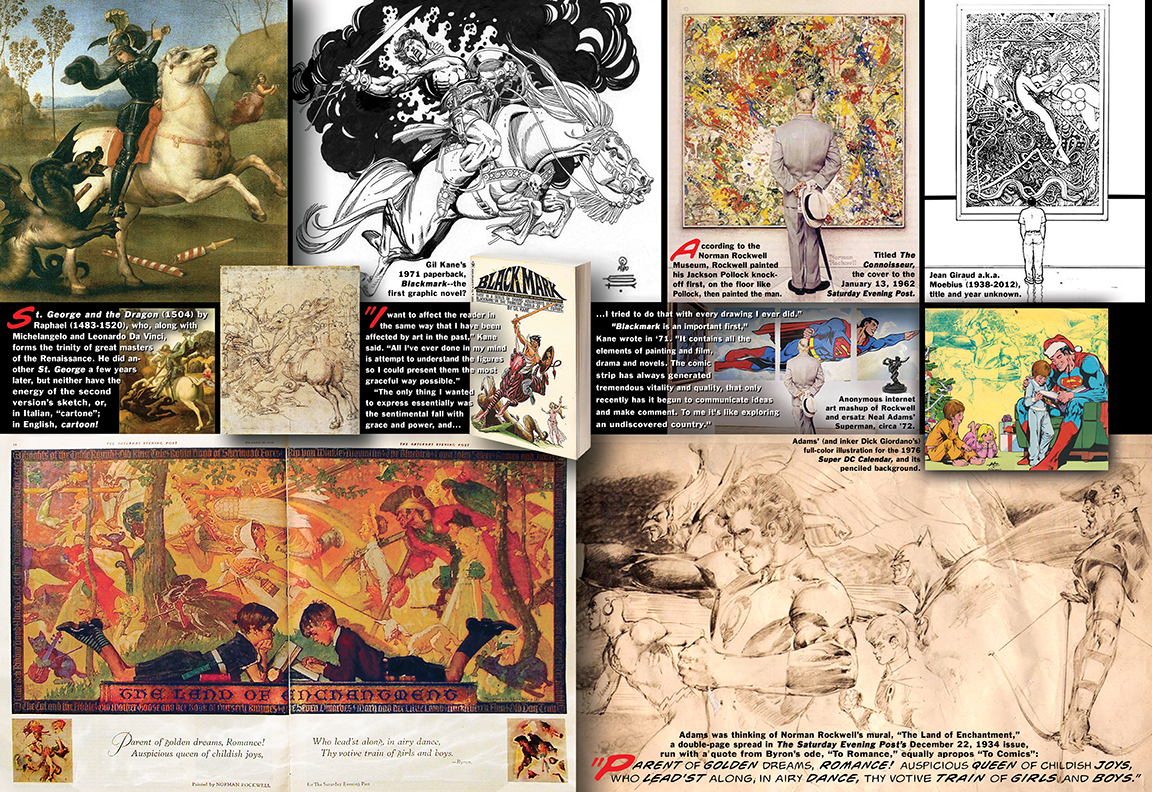

“I want to affect the reader in the same way that I have been affected by art in the past,” Kane said. Like St. George and the Dragon (1504) by Raphael (1483-1520), who, along with Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci, forms the trinity of great masters of the Renaissance. Raphael did another St. George a few years later, but neither have the energy of the second version’s sketch, or, in Italian, “cartone”; in English, cartoon!

Nor do any of them have the energy of Kane’s Blackmark drawings. Blackmark is a Bantam Books paperback published in 1971 that is one of the first American graphic novels, predating other such works as Richard Corben’s Bloodstar (1976), Jim Steranko’s Chandler (1976), Don McGregor and Paul Gulacy’s Sabre (1976) and Will Eisner’s A Contract with God (1978). Blackmark was conceived and drawn by Kane (and scripted by veteran writer and editor Archie Goodwin from an outline by Kane).

“Blackmark is an important first,” Kane wrote in ’71. “It contains all the elements of painting and film, drama and novels. The comic strip has always generated tremendous vitality and quality, that only recently has it begun to communicate ideas and make comment. To me it’s like exploring an undiscovered country.”

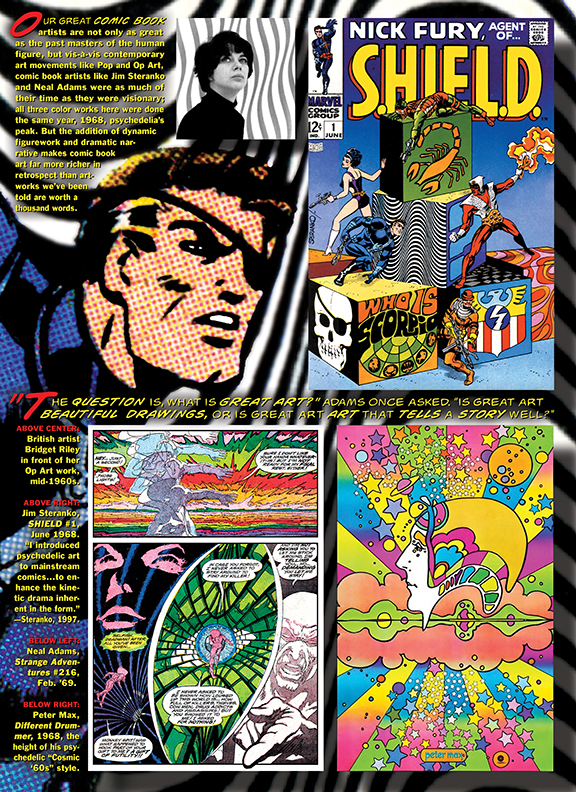

Our great comic book artists are not only as great as the past masters of the human figure, but vis-à- vis contemporary art movements like Pop and Op Art, comic book artists like Jim Steranko and Neal Adams were as much of their time as they were visionary; their comic book works here — Steranko’s cover to SHIELD #1 and Adams’ Deadman page from Strange Adventures #216—were done the same year, 1968, psychedelia’s peak, as Different Drummer by Peter Max, at the height of his “Cosmic ’60s” style (Max’s online biography: “From American comic books, radio broadcasts and cinema shows, young Peter formed an impression of the land of Captain Marvel and Flash Gordon…”). But the addition of dynamic figurework and dramatic narrative makes comic-book art far more richer in retrospect than artworks we’re told are worth a thousand words.

“The question is, what is great art?” Adams once asked. “Is great art beautiful drawings, or is great art art that tells a story well?”

—

See Arlen present Art & Comic Book Art as a VisuaLecture at East Coast Comicon April 11! You can also buy his hardcover The Silver Age of Comic Book Art here.

June 23, 2020

This is absolutely groovy. 🙂