If you love comics, love music and want to read something that will reinvigorate your soul, check this out…

Generally speaking, we tend to keep it tight and quick here at 13th Dimension. I’ve long settled into a rat-a-tat-tat patter that seems to fit the nature of what I love to write, read and talk about.

Then something comes over the virtual transom that makes me stop and think and makes me want to share it with readers who also want, or even need, to stop and think.

Putting it plainly, the world sucks right now. These are bad, bad times and we do our best here to brighten your day, provide a little distraction and have a good time when times are very, very tough.

Which brings me to this piece by Silver‘s Stephan Franck, a poly-hyphenate — writer, artist, animator, musician — who’s got a kickass Kickstarter cooking for a graphic novel called Palomino, a neo-noir set in LA’s country scene of the early ’80s. (Click here for more info on the crowdfunding project. Really, do it. You’ll thank me.)

Anyway, Stephan has written a piece for us that doesn’t so much as take you behind the scenes of creating a comic as guide you through a gritty, glorious world where artforms intersect and play off each other, drive through and bounce in the other direction. Just like a great band before a great crowd. Like seeing the King of California himself, Dave Alvin, tearing it up with the Guilty Ones one minute, and making you tear up the next.

What Stephan has written here will do your soul good. It’s an essay — accompanied by pages from the book — that’s deeply personal and profoundly universal at the same time.

Just like your favorite comic. Or your favorite song.

Enjoy. — Dan

By STEPHAN FRANCK

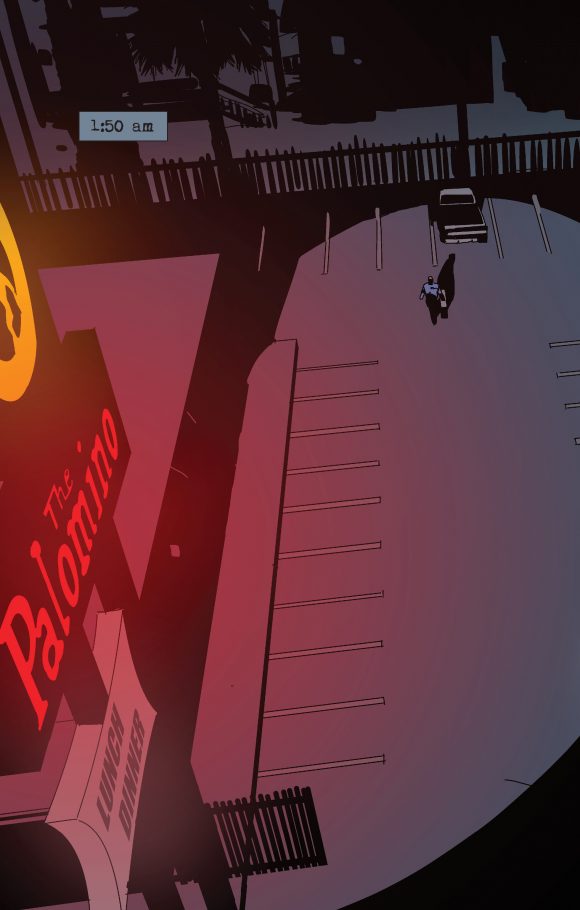

Everyone’s life has different strands that run in parallel and may never connect. For most of the creative journey that took me from growing up in a small blue-collar town in France, to calling Los Angeles my home for most of my adult life, it seemed that playing music and making comics would remain separate, parallel realities, until my new graphic novel Palomino, a neo-noir set in LA’s legendary Palomino Club, finally brought them together.

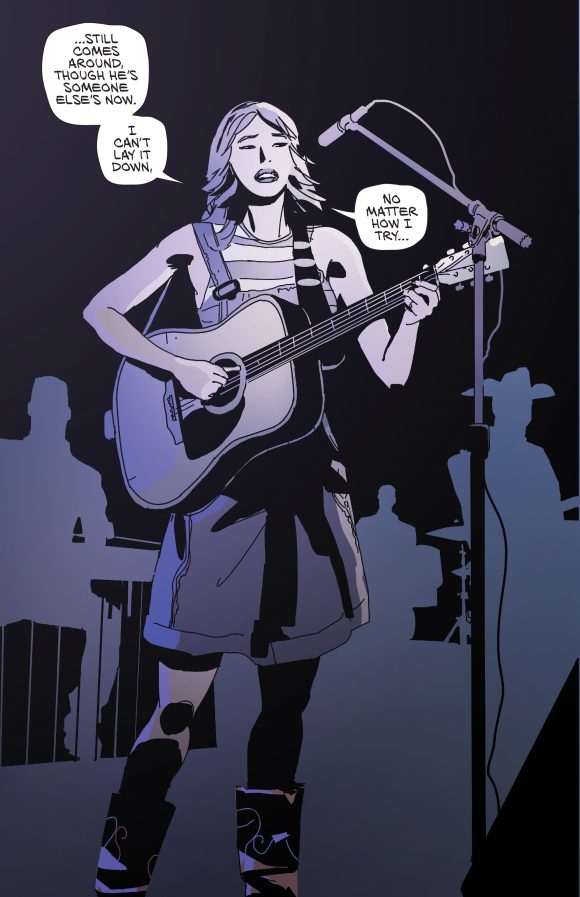

When creating a comic book about music, the first intangible is obvious: How does one express a sonic, emotional experience in pure visual terms? The first step was to accept that symbols were not going to help. By symbols, I mean the visual representation of abstract concepts, such as literally drawing musical notes to illustrate the fact that music is being played.

Few comics readers can look at a piece of written music and hear it in their head, let alone have any emotional connection to it. I know I can’t, and it was immediately clear to me that having musical notations written on the page would only separate the reader from the moment, not create an immersive emotional experience. Instead, I had to find a way to draw that intangible and “represent” the music.

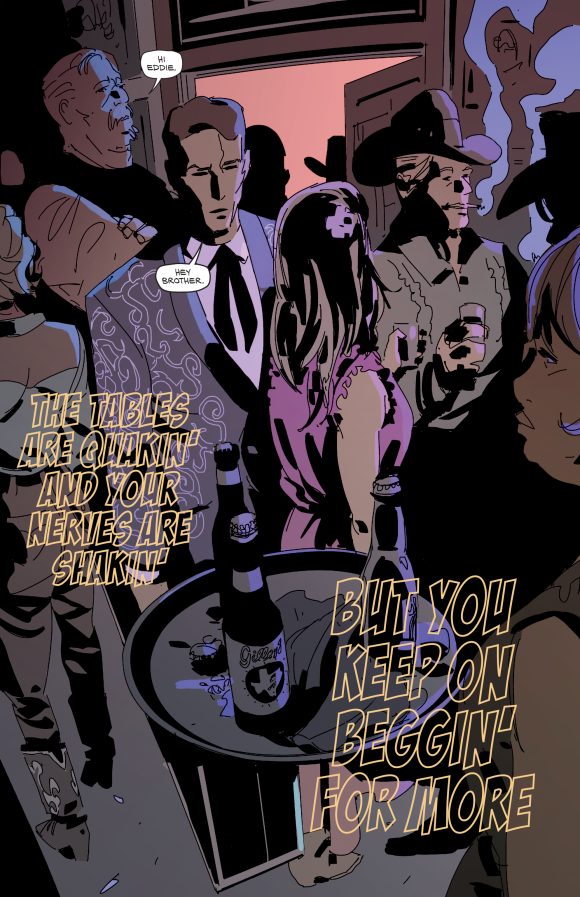

I approached it the exact same way that any emotion is represented in any scene — by capturing the way the characters interact with it. To capture the musicians’ energy as they performed. To describe their intensity, their mood, and to observe the experience of the other characters in attendance. Also, as anyone who plays music knows, it is as much about the notes that you don’t play as about the ones you play. It’s about silence. It’s about intervals. In other words, music is about space. So are the visual arts.

Comics in particular, are very adept at spacing their visual elements — text included — to recreate a sense of cadence, phrasing, volume, and delivery, and to bring a moment to life. So when music played, I resisted the temptation to fill the space with visual noise. To the contrary, I chose to leave those spaces open. To keep the music itself invisible, yet to have it claim its own space in the image. In other words, music would be to the comic page what dark matter is to the universe. Although unseen, the reader would feel its presence by feeling its effect on the characters.

Last but not least, color — from red hot to deep blue — would literally be the emotional palette of the musical moments. But as deep as I dug into my artistic bag of tricks to bring Palomino to life, creating it as an artist would only take me so far. To really feel authentic, Palomino needed to be drawn by a musician.

Growing up as a comic book fan and an aspiring artist, I couldn’t help but notice how two things always looked generic and wrong in comics: musical instruments and cowboy hats. Somehow, it seemed as if those two types of geek culture didn’t intersect.

For me, things were different. My parents had a store on the outskirts of Paris. “The Store,” as our whole family called it, provided the community with life essentials such as cigarettes, school supplies, and lotto tickets, but most importantly, it was the neighborhood’s cultural hub. Newspapers, magazines, books, comic books, and for a while, records, we had it all.

As my mom did her best to stay up on the Top 40 records, as well as trying to figure out what comics the kids were reading these days, I started developing a sense that all these forms of creative expression belonged together. Then, around 1980, the Stray Cats landed on our shores, and became the gateway band that single-handedly brought rockabilly into the lives of European kids of my generation.

Thanks to the Cats, we discovered Sun Records and all the types of roots music associated with it — blues, rhythm & blues, hillbilly music, bluegrass, honky tonk, and expanded from there. I had received some music training since an early age, but it had never really clicked for me until I held a guitar in my hand. Then it was love.

As woodshedding quickly turned into local gigs and the neighborhood kids with instruments were replaced by young musicians on a professional track, the community centers turned into festivals and clubs. Just like with writing, drawing, and filmmaking, playing music became part of the experience –the life project.

While the rawness of rockabilly obviously spoke to my own sense of teenage rebellion, the guitar stylings of James Burton led me to California country rock. The album that captured my imagination above all was a live LP by Emmylou Harris called Last Date.

Somewhere in the liner notes, it was mentioned that the album aimed at “capturing the spirit of the California Honkytonks.” Huh. I kept that on file. Next was the Desert Rose Band, whose first album had a photo of the band in front of the Palomino Club. JayDee Maness’ pedal steel guitar in particular was the element that made the DRB’s sound unique to my ears.

This might be a good time to mention that, although the Telecaster was the thing for me, my favorite instrument to listen to is actually the pedal steel guitar. This might also be a good time to resist falling down the rabbit hole of trying to analyze why I like it so much, but the simple truth is that the sounds of Lloyd Green and JayDee Maness always made me dream.

I also find that steel guitarists often have a way of talking about their craft that resonates across any other artform that lives where art meets commerce. Like Lloyd Green’s quote about an accompanist needing to know how to be “the other voice in the song,” or Pete Drake’s deep truth of the universe that “there is no money above the 5th fret.” It is an instrument full of moving parts and hidden mechanisms, yet it is used to produce some of the most nakedly emotional sounds in popular music, and there is an old-soulness to its practitioners that makes it the perfect musical metaphor to associate with the main character of a noir story.

Meanwhile, it’s animation that took me to Hollywood for a career in film and comics, bringing me to the source of the music I loved and allowing it to transform from musical inspiration into becoming an actual part of my life. The Palomino Club had closed in 1995, right before I arrived in LA, so I never was able to see it in action. However, I quickly found out that, while the LA country rock scene was not as active as it had been, there definitely was an afterglow. The musicians were still here, and some of the clubs still open, especially thanks to the ’90’s “New Country” fad.

And as I started to play the clubs, little by little, I had the opportunity to meet, work, become friends with many of the amazing musicians who had inspired me in the past, and to share some life adventures with them. Those adventures — the texture of life in the music clubs — is the next intangible that Palomino had to get right in order to work.

A great actor once told me that “Specificity is the mark of artistic maturity.” In that sense, Palomino is my most mature work to date. Drawing the gear and the instruments right was of course crucial, which, as I mentioned earlier, is something I had always missed seeing in comics. A lifetime of being around music hopefully made that possible — although I have to admit that a steel guitar player pointed out to me that in one of the panels, the neck on Eddie’s Emmons’ guitar looks a lot like a Zumsteel. He was right! But, come on, that Gretsch White Falcon that I have in a couple of panels is not too shabby!

It is more than the gear, however. It is the overall vibe, and – again — the intangibles. Like how musicians in the house band stand when an unknown singer walks on stage. It’s how some of the people on the dance floor seem more into their steps than into the music. It’s the way the musicians are greeted by the regulars as they enter the club. It’s the feel of those empty beer bottles passing by on the waitresses’ tray. It’s everything.

Palomino is also about a way of life that used to be, but no longer is. When I endeavored to tell a story about working musicians in 1981 Los Angeles, I didn’t initially grasp how much the picture it painted mirrored changes in society at large, and the path that we have been on for the last 35 years. You see, “working musician” isn’t just a turn of phrase. It used to be a thing. People used to be able to have a good middle-class life, raise a family and buy a house in the Valley by being club musicians. Working five or six nights a week, with a few local TV show gigs here and there, and a few sessions once in a while.

But things are different now. Those jobs just don’t exist anymore. One person to hold such a job was my dear friend, the late great drummer Archie Francis. Archie was the house drummer at the Palomino for 30 years, the premier country drummer in LA, and multiple ACM Drummer of the Year award recipient. And as fate would have it, Archie lived across the street from me.

By the time Archie and I became friends and I started to play guitar with him, his drumming days were mostly behind him. However, as it turns out, Archie was an incredible songwriter. While spending a lifetime as a sideman, Archie had written or co-written hundreds, if not thousands of songs, each one catchier, more clever and poetic than the next. Gems like I Don’t Wanna Die With Money in the Bank, or I Need A Saturday Night in the Middle of the Week. Talk about finding grace and deep human truth in small things, Archie was a master. But he was also the king of irony, and the song of his that was his favorite — his anthem, if you will — was a goofy tune called Corn. “Corn, corn, corn, buy my corn!” was the chorus. “Buy my corn.”

Archie knew that, at the end of the day, we — artists in the popular arts — we’re all selling corn. While Archie originally hailed from Kansas, it really is California corn he had been selling all his life. Few people still remember that, from Roy Rogers to Dirty Harry, from John Wayne to Ronald Reagan, and from Spade Cooley to the Eagles, Southern California had mostly been in the business of selling “the Cowboy” — the aspirational linchpin of the American Century — to America itself and to the rest of the world. Corn.

After a few years of friendship and countless gigs together, I visited Archie on his deathbed. Doing his best to accept that he had reached the end of his road, and hoping to encapsulate the moment, he once again stumbled onto some new Archie-ism. The kind of simple truth that makes you amazed that you’ve never heard it put quite that way before. We looked at each other. “That’s a song,” he said. “Get my book.”

I fetched the notebook full of song ideas that he kept under his pillow, but he was too weak to write himself. So I wrote the phrase in it for him, and he made me repeat it to make sure I had written it right. “There,” he said. “For later.”

Animation or comics students often ask me about life as a professional artist, and most of their questions revolve around the wish that the existential experience of creating art changes over a lifetime. Spoiler alert: It doesn’t.

Whether you’re a 6-year-old kid trying to draw Batman for the first time, or an old poet cowboy dude on his final day, it’s about that moment when capturing the intangible seems within reach.

The truth is right there, just a few words, a few notes, or a few sketch lines away, and the feeling that if you can manage to capture it, everything will be right with the world. And of course, you never really quite capture it, and of course there is so much about the world that is not right.

But as long as the artistic journey continues, there’s always next time.

—

For more info on the Palomino Kickstarter, click here.

—

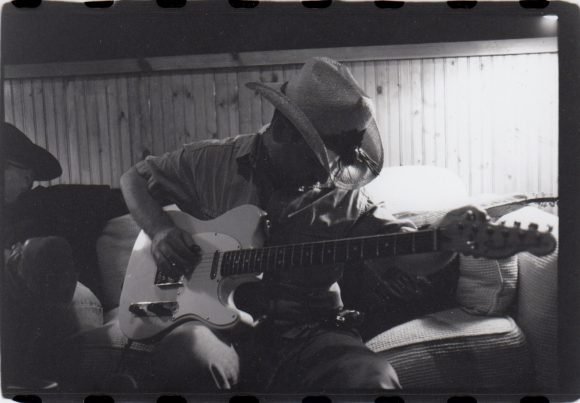

Stephan at the guitar

Stephan Franck is an animator/writer/director/comic book creator. He was a supervising animator on the cult classic The Iron Giant, and contributed story to Despicable Me. He co-created the animated TV series Corneil & Bernie and has closely collaborated with talent as diverse as George Lucas and Adam Sandler. In 2013, he founded comic-book publishing and production company Dark Planet. Silver, his graphic novel debut under the Dark Planet banner, earned a nomination for the prestigious Russ Manning Award at San Diego Comic-Con 2014. Click here for more on Dark Planet and Silver.

—

MORE

— 13 Visual Storytelling Tips For Comics, by Stephan Franck. Click here.

— SILVER’s Stephan Franck Picks 13 GREAT VAMPIRE COMICS. Click here.