Just in time for Halloween comes this list of 13 comic-book monsters to suit the season.

—

UPDATED 10/26/17: Halloween’s a-comin’! Here’s a fantastically feral list of 13 GREAT COMIC BOOK MONSTERS. This first ran in 2015 but so what? It’s still fitting! Dig it!

—

From otherworldly beasts to creatures of a more interpretive nature, author Samuel Sattin of The Silent End has compiled a versatile selection of beasties to sate your grim appetite.

—

By SAMUEL SATTIN

1. Charlie Manx (Wraith: Welcome to Christmasland)

Charlie Manx originally appeared in Joe Hill’s NOS4A2. A necrotic, child-abducting soul vampire, Manx hones in on the young ‘uns, promising them an escape from the ills of the world, and then using his Rolls Royce Wraith to traverse pockets of altered reality to do so. His destination of choice? An amusement park/grand guignol known blithely as Christmasland. Wraith: Welcome to Christmasland was Manx’s debut in the land of comics, drawn by C.P. Wilson III with variant covers by Gabriel Rodriguez, and as I’m sure you can infer, nothing short of a nightmare ensued.

—

2. Dodge (Locke & Key)

Dodge is a demon from the other side of what is known as the Black Door in Joe Hill and Gabriel Rodriguez’s epic horror masterpiece, Locke & Key. Also referring to itself as the Legion, Dodge takes multiple forms, and in its quest to reopen the Black Door, conducts a series of nefarious experiments in sociopathic subterfuge, fulfilling its role as a genuinely fearful entity whose ill regard for human life is palpate.

—

3. Swamp Thing

If we’re going to talk about monsters, we have to acknowledge the good and righteous among the flock. Swamp Thing, most notably with Alan Moore at the helm, is pretty much a reconstituted vegetable-entity, reformed in the image of scientist Alec Holland when, after being caught in a chemical fire, he jumps into a swamp to save his life. Some time later, the creature known as Swamp Thing emerges, thinking of itself as Holland reborn. Though the author makes it known that the creature is not Holland per se, but an entity that has absorbed Holland’s memories and likeness, a phantasm of sorts, in its own right. Swamp Thing’s adventures are the stuff of psychedelia, with the occasional bad trip.

—

4. The Spiral (Uzamaki)

Junji Ito’s Uzamaki has recently transitioned from the realm of the obscure. Ito’s unique interpretation of horror borrows from a variety of traditions, providing a new spin on madness and the grotesque. This can be seen especially in Uzamaki, where the monster is no less than a shape. Ito’s insidious Spiral infiltrates the ether of a small Japanese town, imbuing its reality with bloody contortion, until the town itself becomes a nightmare ouroboros, with no escape.

—

5. Godzilla (Godzilla: Half Century War)

OK, so Godzilla wasn’t born in comics, but he does endure there, reimagined and re-endeavored time and time again, as seen here in this page by James Stokoe. In the same way there exists writer’s writers and comedian’s comedians, Godzilla is somewhat of a monster’s monster. Its size and scale alone allow for a grandiosity of purpose so overstated it’s comforting. Also, the fact that the beast has fascinating historical origins adds to its allure, not to mention the fact that its trademark roar is actually the sound of a leather glove coated in pine-tar resin being dragged over a double bass.

—

6. Tetsuo/Akira

Like many monsters, Tetsuo from Katsuhiro Otomo’s unparalleled Akira, is a sad case. Picked on and disrespected as you’d imagine the runt member of any run-of-the-mill, testosterone-fueled Neo Tokyo biker gang would be, we’re not all that surprised when, after discovering himself in possession of reality-bending psychic powers, that he goes full Caligula. Really, is anything truly scarier than a scorned, angry pubescent boy on mind steroids? The answer is no.

—

7. The God Warrior (Nausicaa: Valley of the Wind)

Hayao Miyazaki’s manga collection that preceded the film is a superior work of environmental critique, confronting the failures of evolution and the poison associated with human self-preservation. The film is great as well, but only in the comic can you truly understand the might and wonder of the God Warrior, an organic machine created to ensure our own destruction. The truly scary elements of the God Warrior are revealed in the manner of its mindset, which is similar to that of a young child, bonding to Nausicaa under the impression of her being its mother.

—

8. Johan Liebert (Monster)

Naoki Urasawa has been making expert manga since the world was young. But with Johan Liebert, the chief villain of Monster, he truly outdoes himself. Liebert is Michio Yuki (from Osamu Tezuka’s MW) in focus, Hitomi (from Suehiro Maruo’s Panaroma Island) in repose. A master of deceit, and an intelligent facilitator of destruction, this is a human monster without supernatural ability that seems to possess it all the same.

—

9. Ozymandias (Watchmen)

Adrian Alexander Veidt is undoubtedly a monster, but a monster of human idealism. This Watchmen mega-villain, in peak physical shape, with charm and affability and brains and brawn, is a stand-in for every person’s tendency to think he/she can make decisions for the whole of humanity. Ozymandias’ form of decision-making in this case is an egoistic envisioning of a peaceful future only attainable by killing off millions (which he succeeds in doing) and blaming it on a being of pure physical curiosity to unite everyone against a common enemy. Veidt is precisely so monstrous, then, because in some ways, we understand him.

—

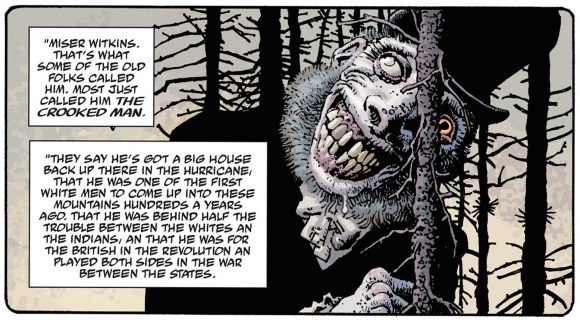

10. The Crooked Man/Hellboy

I don’t know if commentary is really required for this one. Let’s just say that the Crooked Man was hung for horrible crimes, but sent back to earth from Hell following a pact with the Devil. But really, it’s that face, isn’t it? That horrible, horrible face.

—

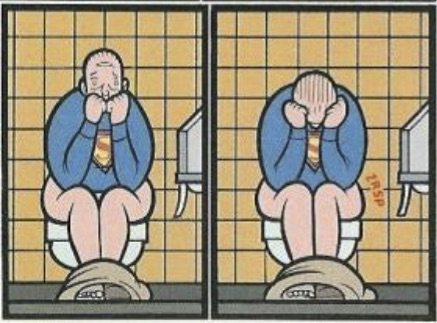

11. Depression (Jimmy Corrigan)

I’m being a little cheeky here, but I must admit that when I first read Jimmy Corrigan I had nightmares for a month. The wear and tear of Chris Ware’s bleak vision is a beast in its own respect, tapping into one of the most monstrous of all intangible entities: mental illness. The monsters we create come from the darkest parts of us; horror wouldn’t exist without anxiety, fear, sadness, and yes, the actual chemical imbalances inside many of our brains.

—

12. STD/Black Hole

This one’s a little cheeky as well, but if we’re going to talk about monsters, why can’t we mention one of the scariest of all? Sexually transmitted diseases, exchanged like Camel Cash among those of us (read: near-all of us) whose instincts at some point have trumped safety, leave behind welts, discharges, warts, and far, far worse. Charles Burns taps into that fear in the smartest, and scariest, of ways, with an STD that transforms young ‘uns into monsters of their own regard.

—

13. The Pixies (Beautiful Darkness)

These guys are the worst. This entire book is a vision in turning convention on its head, remixing Lilliputian whimsy with Thomas Ligotti’s Songs of a Dead Dreamer. Our little Pixie friends, with their dollhouse clothing and animal familiars, are slowly revealed to be instrumentations of sadistic opportunism and fascism. Of course, Beautiful Darkness is a heavy-handed allegory for the human condition, but it’s also just discomforting. You’ll never think of Pixies in the same way again.

—

Samuel Sattin is a novelist and essayist. He is the author of the critically claimed horror novel, The Silent End, and League of Somebodies, described by Pop Matters as “one of the most important novels of 2013.” His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Salon, io9, Kotaku, San Francisco Magazine, Publishing Perspectives, Black Gate Magazine, Fiction Advocate, LitReactor, The Weeklings, The Good Men Project and elsewhere. He has an MFA in creative writing from Mills College and an MFA in comics from CCA. He’s the recipient of NYS and SLS Fellowships and lives in Oakland, California.

November 8, 2015

Cool feature, definitely enjoyed this list, especially curious about the subtlety creepy Beautiful Dreamers one. The beautiful, innocent-looking water-color art is so that it betrays the hidden brutality and horrific theme of the book. Nice contrast.