REEL RETRO CINEMA: New looks at old flicks, and their comics adaptations…

By ROB KELLY

Anyone who has read superhero comics with any regularity has, at some point, let themselves imagine what superpower they would most want to have, if given the chance. When asking this question, you’ll most likely get the same few answers: flight, super strength, telepathy—the kinds of abilities that seem to most inspire awe and wonder in all of us earthbound creatures.

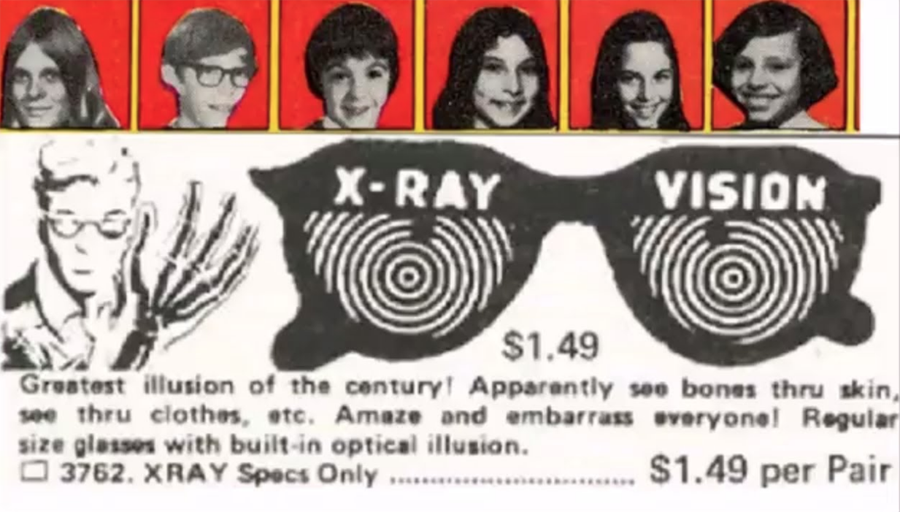

Not far down on that list, it’s safe to say, is x-ray vision. The idea of having a power that you can use and no one is the wiser is just too irresistible for a lot of people, especially the dominant demographic for superhero comics: young males. There’s a reason why x-ray specs were a staple of the kitschy junk advertised in comics for many decades.

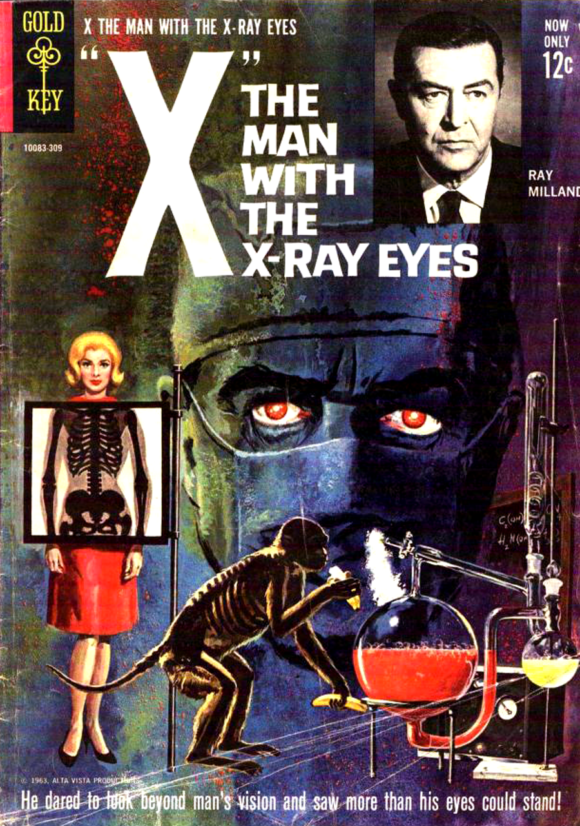

Roger Corman’s film X (titled X: The Man With The X-Ray Eyes in advertisements only) — released Sept. 18, 1963 — starring Academy Award-winning actor Ray Milland (The Lost Weekend, Dial M For Murder) takes that undeniable hook and runs with it from the first scene, where we meet Milland’s Dr. James Xavier, already deep in his research on how to increase the range of human vision. By his estimation, humans can only see one-tenth of the visible spectrum, and he thinks he has developed a formula to peer into the ultraviolet and x-ray wavelengths. He experiments on a monkey, and almost immediately his suspicions are confirmed: The little creature appears to be able to see through solid objects. At this point, Xavier is off and running, despite the protestations of two colleagues, Dr. Sam Brant (Harold J. Stone) and Dr. Diane Fairfax (Diana Van der Viis, who looks like Sue Storm come to life).

Xavier then experiments on himself, and immediately he is able to see through solid objects, as well. When consulting on a medical case involving a young girl, he is able to peer into her chest and determine what her real problem is. No one believes him of course, but that doesn’t stop him from slicing the hand of the surgeon about to operate, so Xavier can take over and show everyone he was right. Things accelerate from there, and soon Xavier is seeing the world in forms of light and color that his brain cannot fully comprehend. An argument with Dr. Brant goes horribly wrong, leaving Brant dead and Xavier on the run.

Now in hiding, Brant gets work at a carnival as a mind reader. Everyone assumes it’s a trick, but the carnival manager (Don Rickles!) sees that it isn’t, and comes up with a way to make some real money: as a medical diagnostician. Dr. Fairfax tracks Xavier down, who is now forced to wear custom made sunglasses because he can no longer close his eyes to shut out light. Xavier, increasingly erratic and prone to fits of rage, is led away by Fairfax and they drive to Vegas, where Xavier breaks the bank of a casino by winning hand after hand. The casino manager steps in, a fight ensues, and Xavier’s eyes are revealed to be black and gold.

Half mad, Xavier grabs a car and drives away, barely able to see what is really in front of him. After a crash, he staggers to a religious revival. Xavier tells the fire and brimstone preacher he can see the edges of the universe, perhaps even the eye of God itself, which the preacher screams is the devil’s work. Xavier’s response is to pluck out his own eyes.

X is part of a long line of “Don’t Play God” sci-fi movies that filled screens in the 1950s and 1960s, and it is one of the best. Anchored by a committed lead performance by Milland, X packs a lot of story into its brief 79-minute run time. Milland’s career was definitely in its twilight by this point, and while he would soon go on to junk like Frogs and The Thing With Two Heads (both 1972), here he is suitably believable and sympathetic, even as he takes wild risks that the audience knows are going to lead to disaster. As the carnival barker, Rickles plays it pretty straight, supportive and menacing to Xavier in equal turn.

For his part, director and writer Roger Corman is able to utilize his standard low budget very effectively—often it was easy to see where Corman’s money had run out and he was covering as best he could. But in X, he keeps the story relatively contained to a handful of characters and locations, adding in some nice little touches (the dripping paint of Xavier’s skid row apartment, for instance). There’s a rumor that just won’t die that an extended ending was shot where, even after Xavier has torn out his own eyes, he exclaims, “I can still see!” Corman later debunked this, but the legend persists.

In case you’re wondering, did Stan Lee happen to see X while he was developing a certain Marvel superhero team? After all, the lead character is named Xavier, and he develops vision powers that he needs special glasses to control. The answer is, well, Lee may have seen X, but if he did, he probably, uh, marveled at the coincidence: The X-Men #1 hit the stands in July 1963, and X debuted in September 1963. Maybe both Lee and Corman were peeking into another dimension for ideas.

Speaking of comic books, Gold Key published a one-shot adaptation of X, written by Paul S. Newman and is the first published work of comics legend Frank Thorne! Behind a beautiful painted cover by George Homer Wilson, Jr., X the comic plods along as you’d expect for a while, until Page 6, where we get a frightening image of what Xavier’s experiments have done to his poor monkey subject.

The scene with the monkey in the film was hard enough for me to take (I really can’t stand seeing animals in movies—they don’t want to be there, odds are they’re scared, just leave them the hell alone), but the comic takes advantage of being able to do things the movie couldn’t: namely, show the monkey with a look of abject terror on its face — a grim portent of things to come.

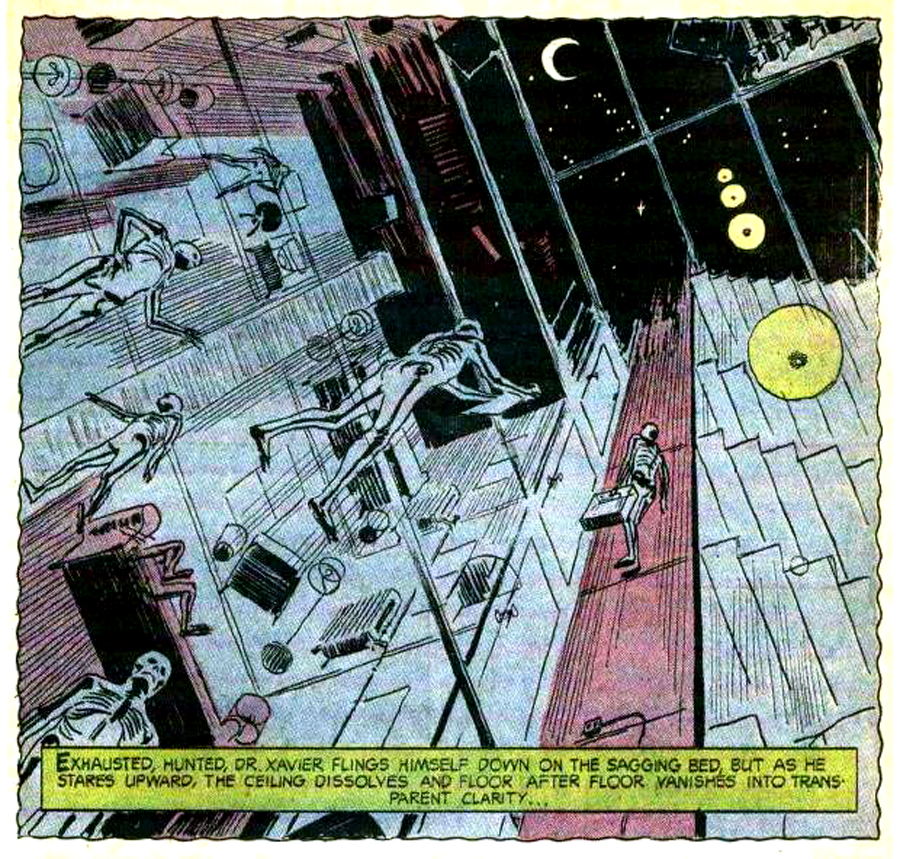

The comic cuts out a humorous scene where Xavier goes to a party and learns to his amusement that everyone around him is suddenly naked (of course they cut that: people were never naked in a Gold Key comic!). Not constrained by budget, Frank Thorne is able to get a little more elaborate with what the world might look like to someone with these newfound powers, and comes up with some really nifty visuals.

Of course, Gold Key had to soft pedal the ending; there was just no way they were going to end their comic book with a guy plucking out his own eyes. Here in REEL RETRO CINEMA I have often given Dell and/or Gold Key a lot of grief for their pallid, dull as dishwater adaptations of really fun source material (Jason and the Argonauts, Tomb of Ligeia), but this time I was pleasantly surprised. Sure, the comic loses some of the flavor of the movie, but it adds some elements that the movie doesn’t have, making for an interesting and slightly more somber read. Ah, if only Gold Key had adapted Frogs and The Thing With Two Heads — that could have made for one hell of a three-pack.

I had the delightful opportunity to see X on the big screen in May, as part of a Science on Screen series at the Enzian Theater in Maitland, Florida. It was preceded by a short talk by a professor, who explained that, surprisingly, the science in X is pretty solid. It was, as I expect Roger Corman hoped it would be, a great way to spend a Saturday afternoon. Go check X out and see if you feel the same—just don’t try and look too hard.

—

MORE

— A Colossus of Adventure: 1963’s JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS. Click here.

— BUCKAROO BANZAI: A 40th Anniversary Salute to Anarchic Film Magic. Click here.

—

ROB KELLY is a podcaster, writer, and film historian. He is the host of podcasts such as Fade Out, TreasuryCast, and M*A*S*HCast on The Fire and Water Podcast Network.