PAUL KUPPERBERG’s DIRECT CREATIVITY: Talking with Roy Thomas, Tom King, Mark Millar, Christopher Priest and MORE…

By PAUL KUPPERBERG

And now, another thrill-packed installment of… My 13 Favorite DIRECT CREATIVITY Quotes!

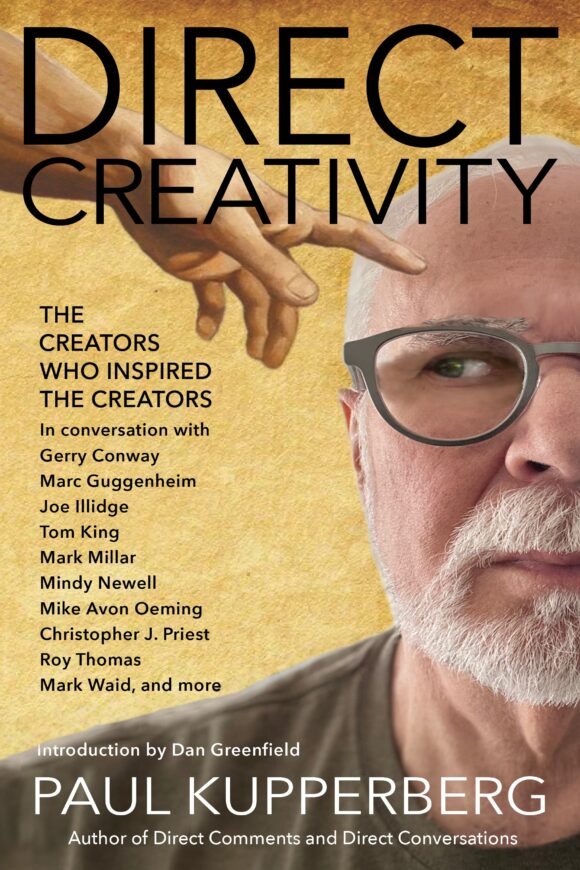

Direct Creativity: The Creators Who Inspired the Creators (with an introduction by 13th Dimension’s own Dan Greenfield!), my next book of interviews with comic-book writers, artists, and editors, is currently kicking it on Kickstarter — please check it out and, if so inclined, support this follow-up to Direct Comments: Comic Book Creators in their Own Words and Direct Conversations: Talks with Fellow DC Comics Bronze Age Creators (both of which are available as add-ons to the Direct Creativity Kickstarter).

The creators are D.G. Chichester, Mike Collins, Gerry Conway, Mike DeCarlo, J.M. DeMatteis, Dan DiDio, Marc Guggenheim, Joe Illidge, Barbara Kaalberg, Tom King, Mark Millar, Mindy Newell, Mike Avon Oeming, Chuck Patton, Christopher J. Priest, Rick Stasi, Roy Thomas, and Mark Waid, and the question I asked them was: Who, or what, inspired you most in your development as a comic book creator?

I’m sharing some of their answers here on 13th Dimension while, of course, simultaneously flogging the Kickstarter campaign, which I hope you’ll check out and support!

Here then, MY 13 FAVORITE DIRECT CREATIVITY QUOTES, PART 3: Stuff I’ve Learned In and Out of School.

—

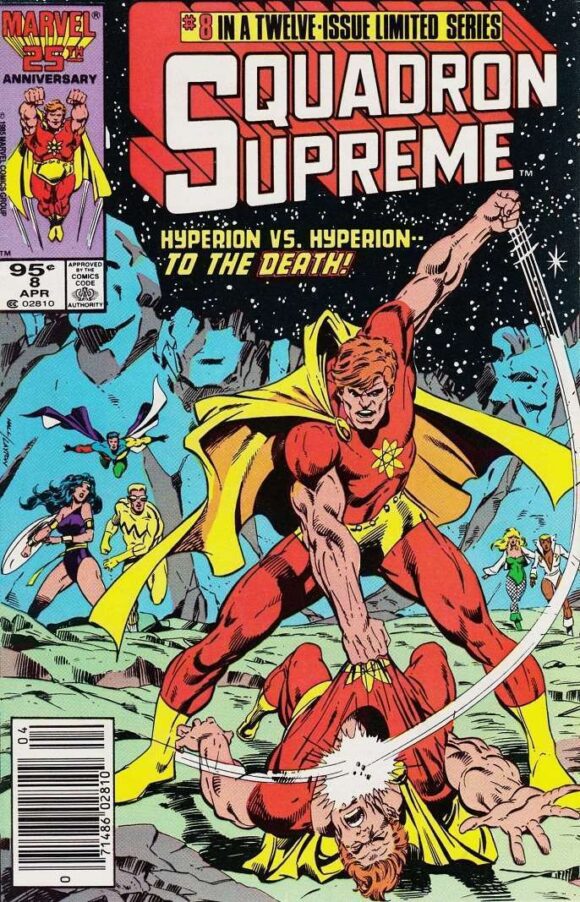

Tom King. “Frank (Miller) was the first guy that made me look at the story and ask, ‘How does he do that? How does he write like this? Where did he learn these tricks that made his stories more than just mindless fights?’ That got me started looking for comics that did the same sorts of elevated storytelling. (Mark) Gruenwald’s Squadron Supreme (1985 – 1986) had a huge impact on me. It was a 12-issue limited series which ended with everybody dying! To this day, I think it’s probably the best comic to take on what’s really the main theme of comics, the idea of superhero-ism versus fascism. And then, of course, I discovered Alan Moore and I read Watchmen (1986 – 1987) which just completely haunted me.”

—

D.G. Chichester. “(Film school) taught me about editing and cutting. The first films I made in school were all very static, with the camera locked down in a master shot and everything happening in the frame. This other student, a junior, took me into the editing room and schooled me hard on cutting. Even if you haven’t moved the camera, cut. Cut, cut, cut, cut. Think about storytelling in terms of shots, or in the case of comic books, panels. Think about how you can frame the moment. Even writing a comic book script Marvel style, I’ve always broken down the shots on a beat sheet, have the storyboard of how things are moving along in my mind. I’m sort of running a film in my head.”

—

Joe Illidge: “My turning point was when a friend of mine said, ‘If you were walking down the street, and you saw your artwork for sale, would you buy it?’ Obviously, If the answer is yes, you should pursue a career. If the answer is no, then you need to do something else with your life. As an artist, I could draw from observation, but not from imagination. The artists that can do this from imagination, the skill, the discipline, the ability is truly amazing. It never ceases to amaze me. And so I went to bed that night having received a blast of ice cold water in the face, and I woke up the next morning and knew that art wasn’t my path. The artwork that I created out of my imagination was nowhere near the level that it would have to be to begin that journey. I was thankful that this person had a frank conversation with me like that. And that I discovered it early enough to find my proper path in my 20s. Because some people don’t get the ice cold water in their face until much later. All part of the origin story, right? It’s the plot twist. Where you want to go isn’t necessarily where you’re meant to go.”

—

Christopher J. Priest. “The best part about being (up at Marvel Comics) was having Jim Shooter explaining story and structure to me. A lot of writers resented him for this, and I understood the resentment. A lot of writers resented it when I would insist on them adhering to the structure as explained to me by Jim Shooter. He had created a sort of template. This is how we tell a story, here’s the personal conflict, here’s where the peaks and valleys go, here’s how to build to the climax. He also explained to me that the reason a guy like Jack Kirby can get away with being so out there and creating in his own style is that Jack understands the rules. And because he understands the rules, he knows how to break them. Once you really get this stuff down, once you’re ready to take off the training wheels, then you can sort of craft your own style and move into your own direction.”

—

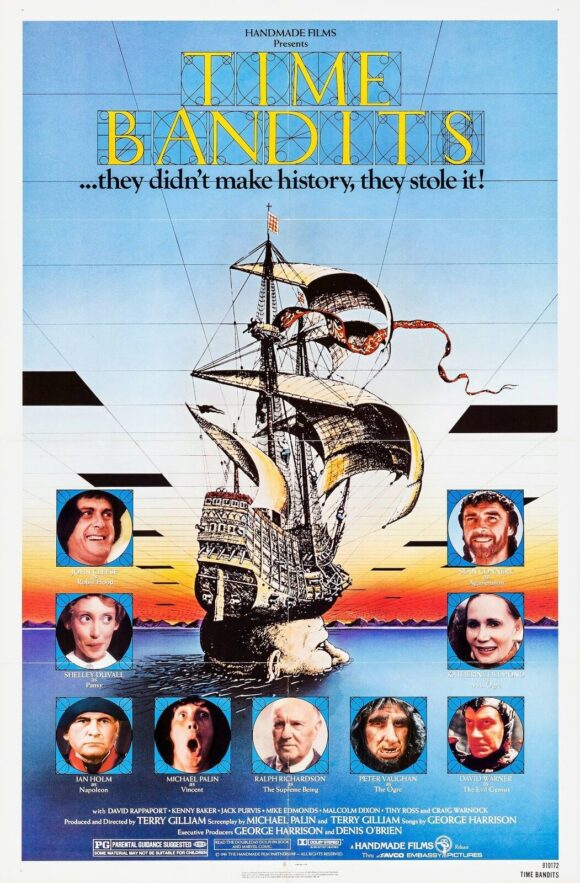

Mike Avon Oeming. “(Artist) David Mack says, when you’re looking for inspiration, just go back to your childhood. And that made me realize everything that I’m doing is a version of either Time Bandits (1981) or Highlander (1986). [Laughter] Some of it even goes back to the old Gumby cartoons. Gumby would run in and out of doors that took him to different worlds and places. Those fantasy films left their mark, along with Star Wars, and the Ray Harryhausen stuff, which to this day I think holds up. I can still watch Clash of the Titans (1981) and there’s a sense of storytelling, an understanding of pacing that’s been lost over the years because they can lean so much on the visual effects now.”

—

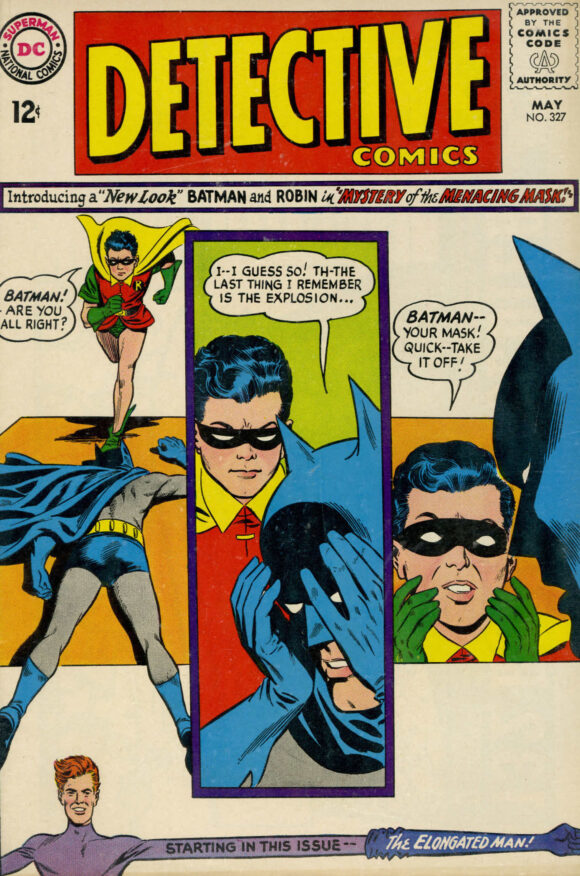

Rick Stasi: “Once my mom saw how seriously I was taking (drawing), she found the only place in town that gave art lessons to kids, the local Jewish Community Center. But when we went there, the person who interviewed me said they didn’t teach drawing cartoons or comic book characters but stuff like bowls of fruit and drapery and still life, and I said I’m out of there. [Laughter] Because I was learning to draw what I wanted to draw from the Superman comics. Tracing Curt Swan was my art lessons. And I moved from that to appreciate the other DC characters, but nothing electrified me like the New Look (Batman) by Carmine (Infantino). And I thought, this is where I want to be. I also loved his Flash. And Gil Kane’s Green Lantern. I loved Mike Sekowsky on Justice League of America. But nothing gave me that shot in the arm like the New Look Batman.”

—

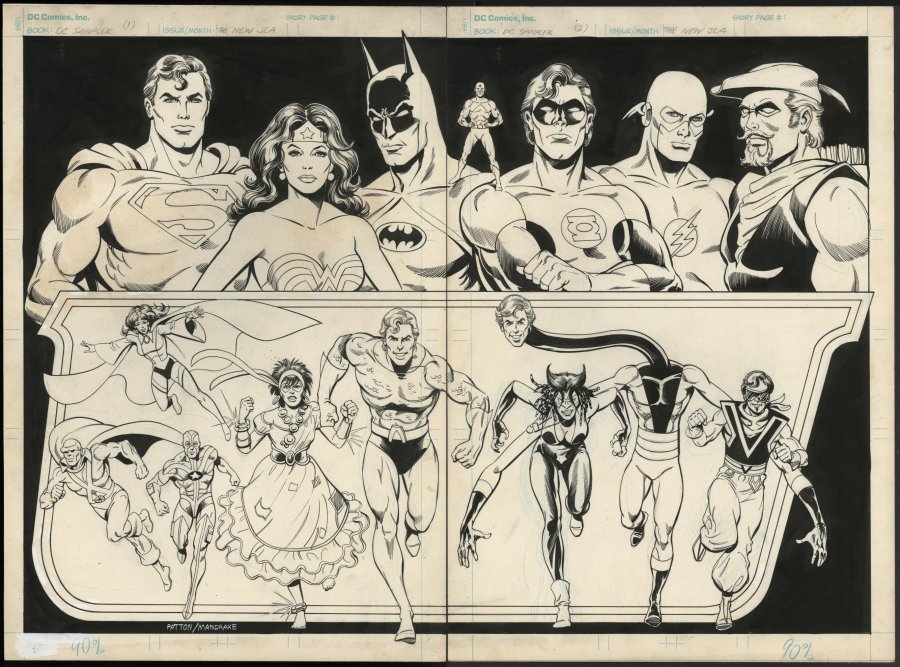

Chuck Patton. “I learned from looking at the stuff I liked and just doing it. Because, again, there was nobody teaching the medium. I never even met anybody intellectually accepting of the medium until my last year of college, someone in academia who respected what I did, and he’s probably the reason I was able to graduate. But up till then I was just bored. I’d gone into college as a journalism major and quickly realized I only had one shot there and what I really wanted to do was draw. So, I switched my major to commercial art, but, you know, I was already 30 years behind the times. I wanted to be an illustrator, and no one in advertising was using illustrations anymore. It was all photography by then.”

—

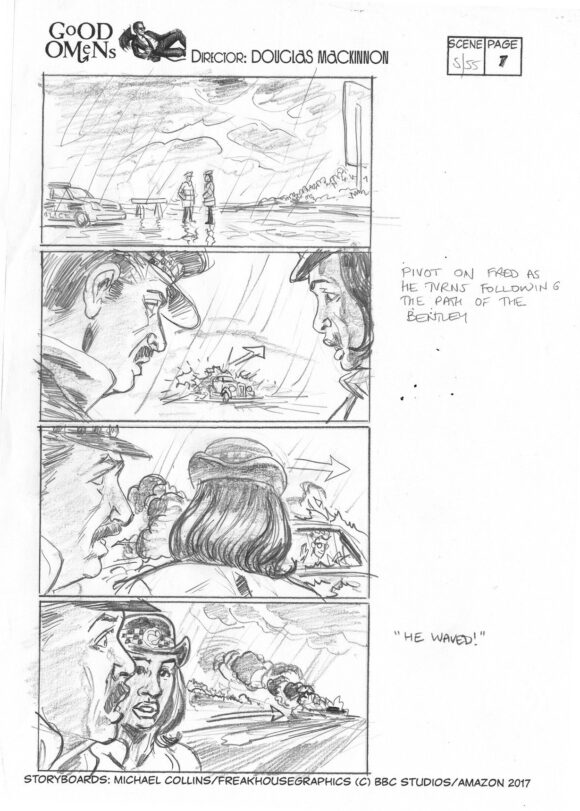

Mike Collins.: “(Comics and storyboards) are very different. It’s all about the grammar of the medium. You’re using the same language in both, but the rules of usage are different. I had a bumpy start. One of the things I had to learn was that in a comic book story you can make the picture any size or shape you like or want, but the screens in TV and movies don’t change. You have to compose everything within that proscenium arch, in that space. But I eventually caught on and since the late 1990s on, I’ve bounced between comics and animation storyboarding. This is a business; you’ve got to go where the work is.”

—

Mike DeCarlo: “I tell people, there’s no shortcut to getting good at anything, let alone art. If you’re not willing to work your ass off for it, there’s someone else out there who is. I say I’ve had 150,000 hours of art in my life and I’m still learning. I don’t sit back and say I’ve learned enough. I can’t. I look at the greats and think I can’t take it easy. It’s a challenge. How do I get to be at least almost as good as that person? The only way I can think to do it is with hard work and study and by not giving up. It’s like the old joke: How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice!”

—

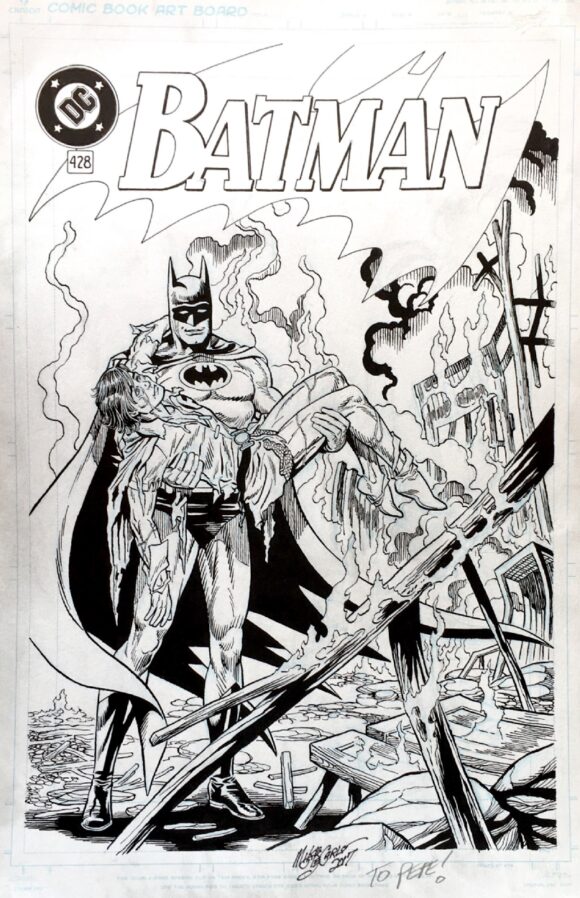

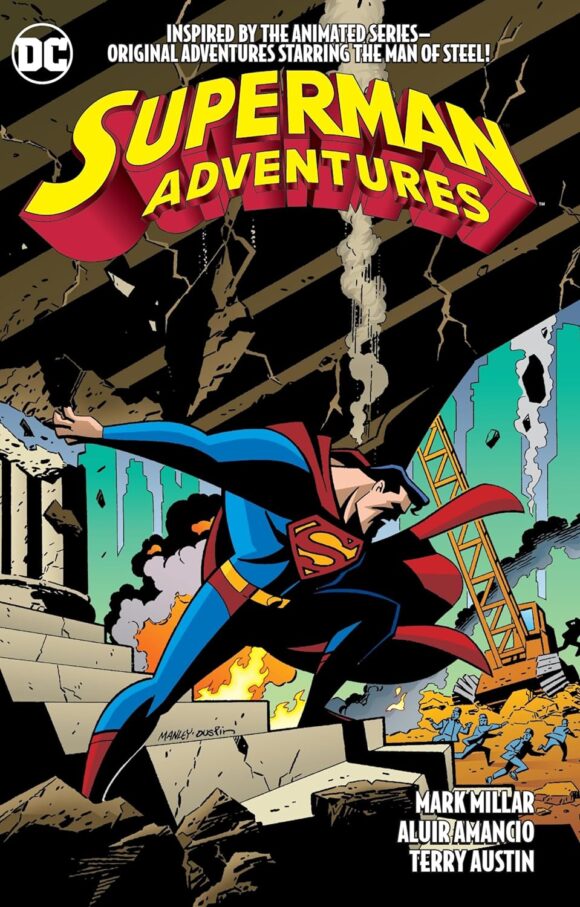

Mark Millar. “You don’t see it when it’s happening but sometimes rejection is the best thing that can happen to you. Like, if I had been given a Superman gig when I first started out, I would have messed it up, and it would have been a disaster. I would be remembered as the guy who wrote a really bad run on Superman. That also goes for when I was in my 20s, when I thought I should be writing Batman or X-Men, one of these big books. Thank goodness they rejected my stories because I’d have ruined my career if I’d come in and done something so high profile, because I just wasn’t ready yet.”

—

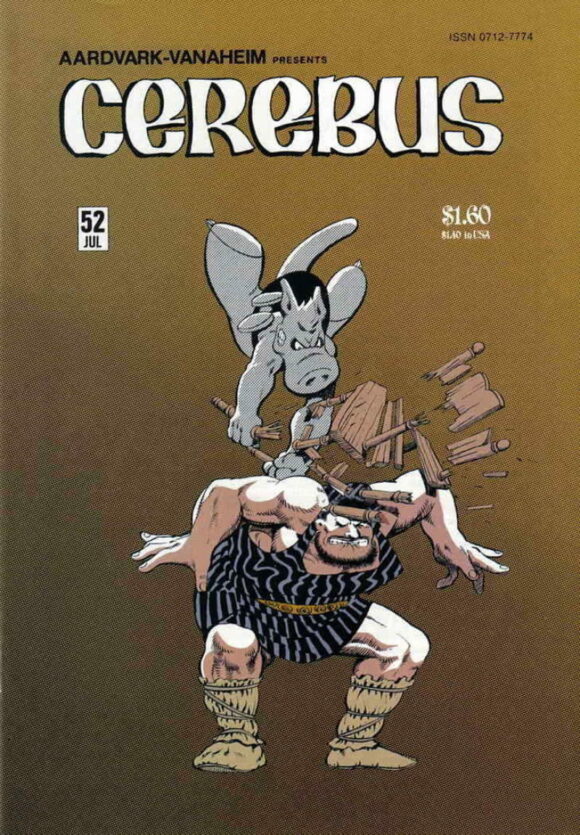

Mark Waid. “The longest and most in-depth conversation I had about craft with anyone in comics to this day was Dave Sim, of all people. I was the schlub assigned to pick him up at the airport for a convention and take him to the hotel. Dave got in early, and he wanted to see Dealey Plaza, where JFK was assassinated, then he wanted to see Love Field, because that’s where Kennedy’s body was taken, so we did the whole macabre Kennedy death tour, but then we went to the hotel bar, and he kept me captive for like, four hours of just talking about things. He had just divorced Deni (Loubert) like that week so there was some of that, but he talked about craft. Not just the pen and the ink of it, but the thinking behind it, writing the character stuff. I wish I could quote chapter and verse, but it was a long time ago, but it certainly left a mark.”

—

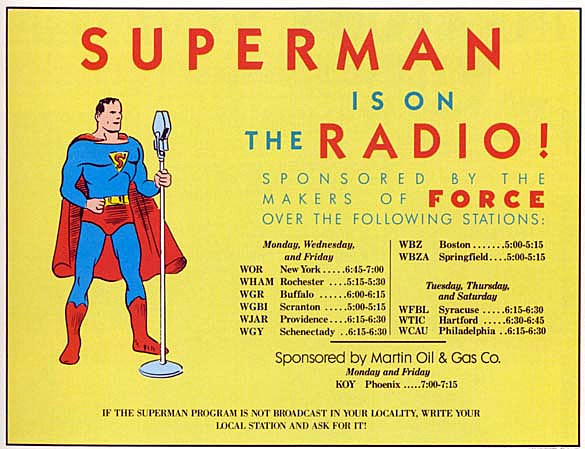

Roy Thomas. “There was something about even bad or not as well written radio that’s easier to accept than in a visual medium. You aren’t limited to whatever picture is on the screen. You might know what the actors looked like from pictures in the newspaper, but most of it was left to the listeners’ imaginations. That’s why superheroes worked on radio, because you could imagine his fantastic feats far better than the special effects of the time could have shown it on the screen.”

—

J.M. DeMatteis. “I must have been 18 when I made my first attempt to write a comic-book script. I had no clue what the format was, I’d never seen one. I wrote some script; I don’t even remember what it was. And I sent it into Marvel, and I got a truly scathing letter back. I mean, it was so, so harsh, from someone who went on to become a fairly well known writer in that era, I won’t say who, it doesn’t matter.”

—

NEXT: Yet another topic and another round of quotes! And not to make too fine a point of it but please check out and support the Kickstarter campaign so Direct Creativity can become a real book!

—

MORE

— PAUL KUPPERBERG: My 13 Favorite DIRECT CREATIVITY Quotes, Part 2: RIGHT PLACE, RIGHT TIME. Click here.

— Paul Kupperberg’s DIRECT CREATIVITY Is Now Live on KICKSTARTER. Click here.

—

PAUL KUPPERBERG was a Silver Age fan who grew up to become a Bronze Age comic book creator, writer of Superman, the Doom Patrol, and Green Lantern, creator of Arion Lord of Atlantis, Checkmate, and Takion, and slayer of Aquababy, Archie, and Vigilante. He is the Harvey and Eisner Award nominated writer of Archie Comics’ Life with Archie, and his YA novel Kevin was nominated for a GLAAD media award and won a Scribe Award from the IAMTW. Now, as a Post-Modern Age gray eminence, Paul spends a lot of time looking back in his columns for 13th Dimension and in books such as Direct Conversations: Talks with Fellow DC Comics Bronze Age Creators and Direct Comments: Comic Book Creators in Their own Words, available, along with a whole bunch of other books he’s written, by clicking the links below.

Website: https://www.paulkupperberg.net/