13 THINGS You May Not Know About the 1965 Classic…

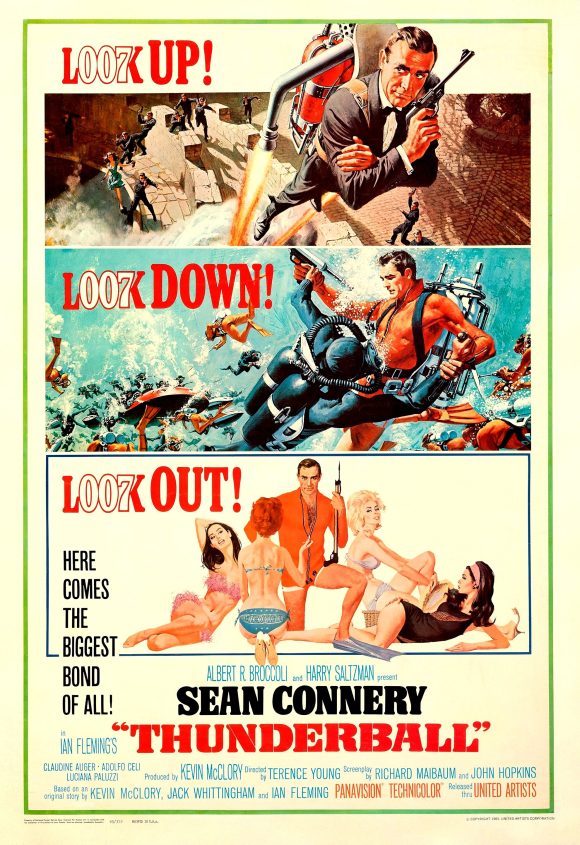

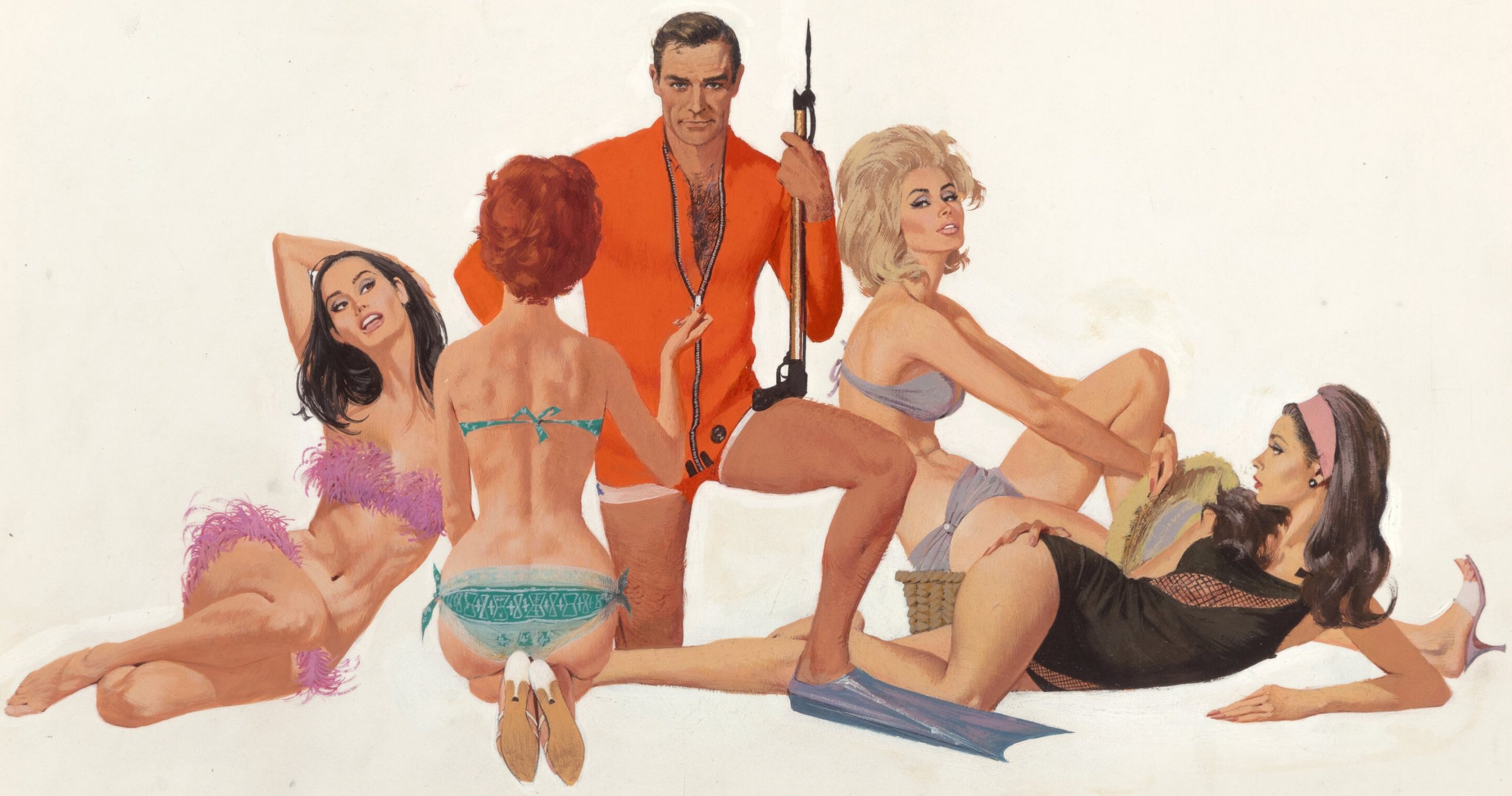

Thunderball’s excellent 1965 movie poster had top and middle paintings by Frank McCarthy and the bottom was the work of Robert McGinnis.

By PETER BOSCH

In 1965, movies and TV shows everywhere exploited the spy craze James Bond had created. The Bond film producers — Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Saltzman — and United Artists knew they had to protect their goldmine by stepping up the game by making Thunderball an epic. The budgets for the three previous pictures ranged from $1 million to $3 million. Thunderball came in at $9 million. Broccoli and Saltzman’s company was Eon Productions, with “Eon” being their shorthand for “Everything or Nothing.”

There are some who say Thunderball was when the James Bond productions lost their specialness and entered the world of just gadgets… but, to me, Thunderball is not only the best of the Sixties’ James Bond thrillers, it remains my favorite Bond movie. Since December 21 is the 60th anniversary of Thunderball’s release in the U.S., and since so much of the film involved underwater action, let’s take a “deep dive” into 13 things you may not know about the film. Enjoy!

—

1. BACKGROUND

Of all the Bond movies, Thunderball was probably the most litigious.

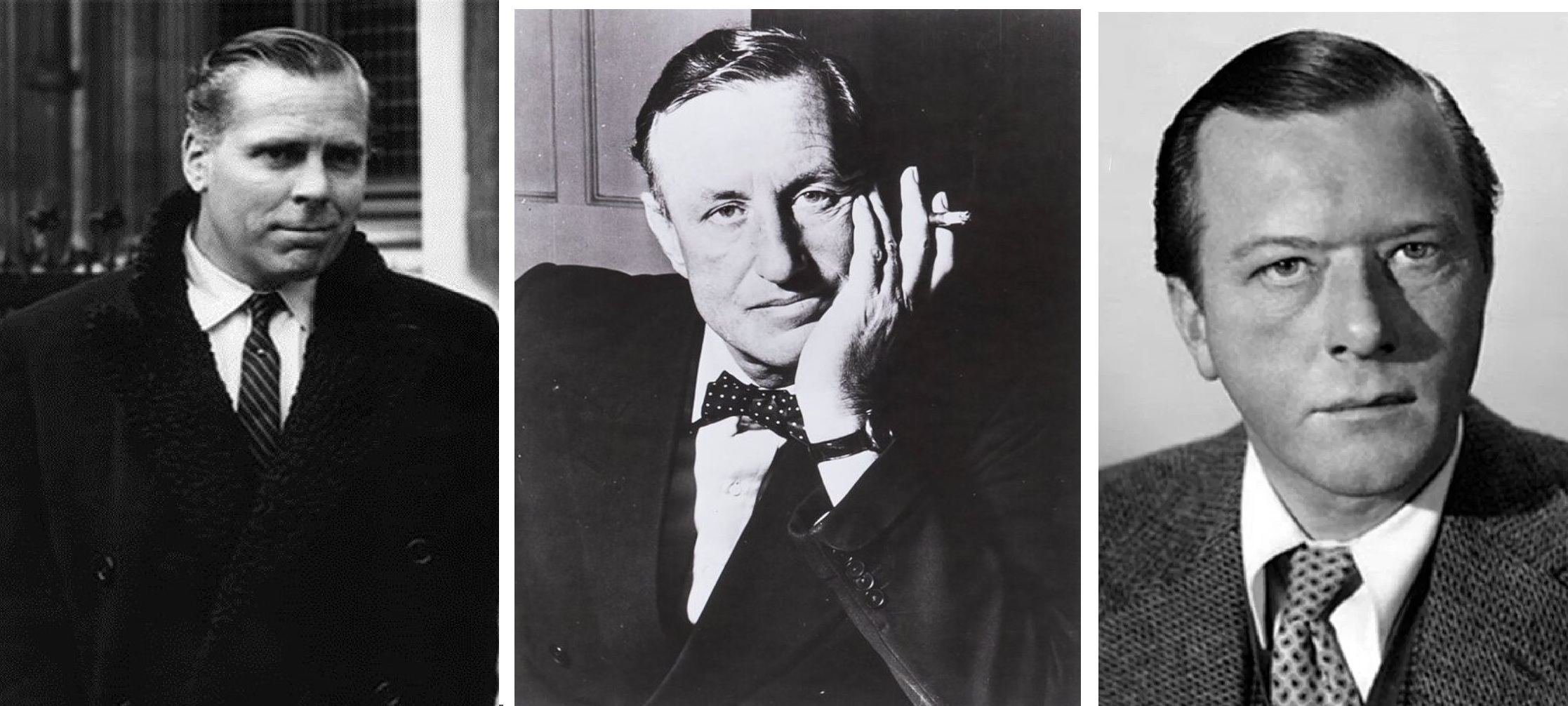

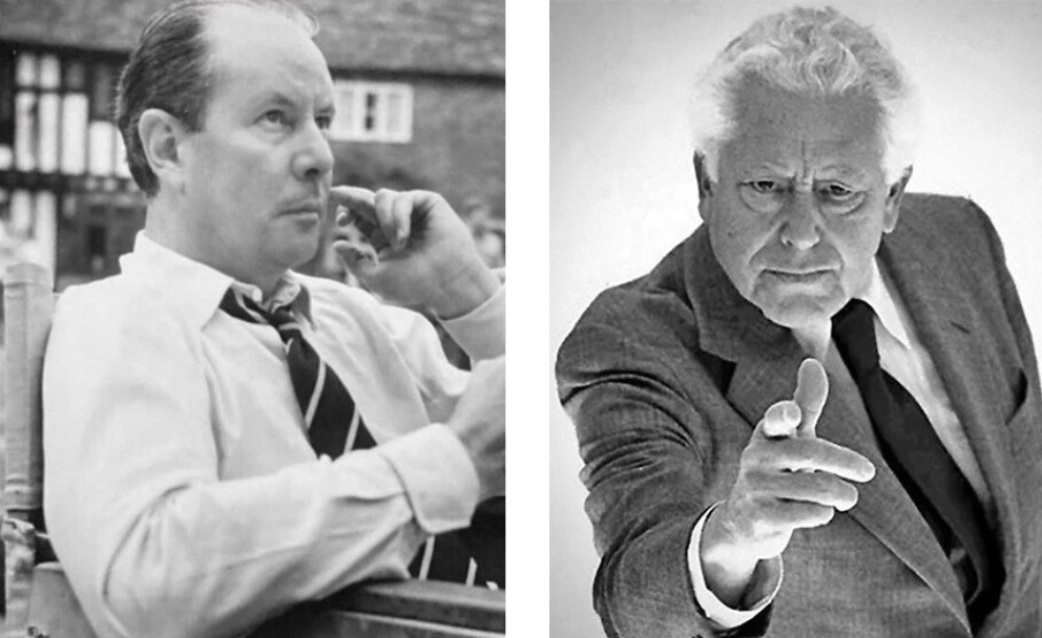

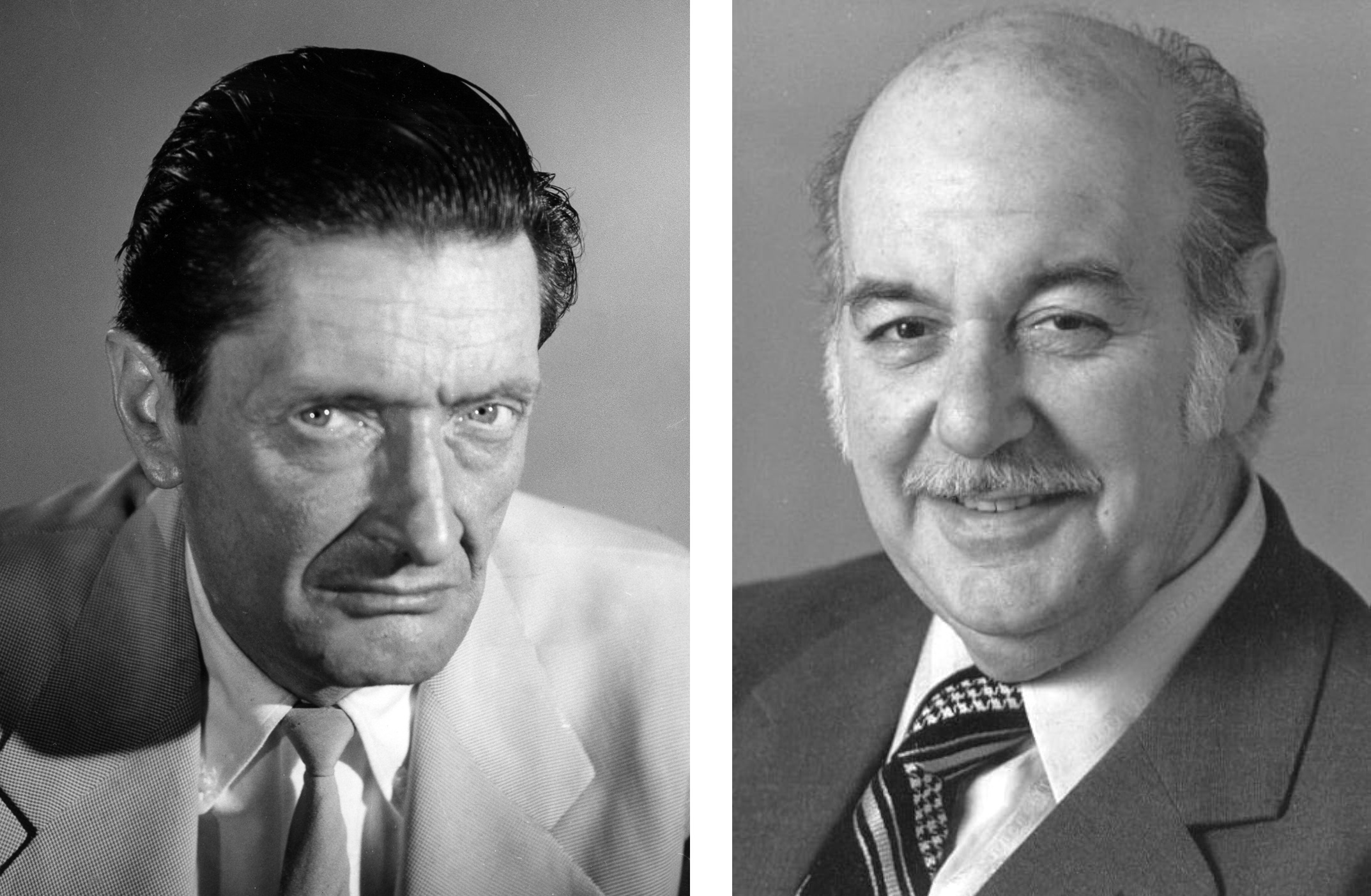

Left to right: Kevin McClory, Ian Fleming, and Jack Whittingham

In 1959, film producer Kevin McClory, screenwriter Jack Whittingham, and Ian Fleming banded together to create a new, original James Bond script because McClory felt that none of the novels lent themselves to a big screen treatment. The screenplay they created was called “Longitude 78 West.”

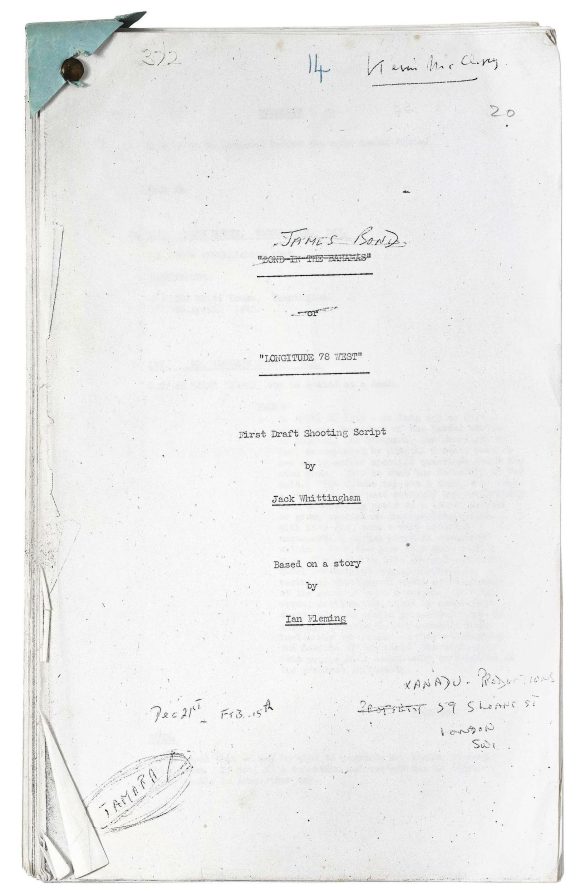

First draft script by Jack Whittingham, auctioned off by Bonhams for £10,000 (about $15,500) in 2013.

Fleming did some rewriting, renamed it Thunderball, shopped it around but got no takers. It’s also been suggested he backed out of the project due to feeling nervous that McClory’s only movie as a producer, The Boy and the Bridge (1959), which McClory also wrote and directed, was a critical flop. With no film deal in sight, Fleming decided to adapt Whittingham’s script into a new James Bond novel, which he still called Thunderball.

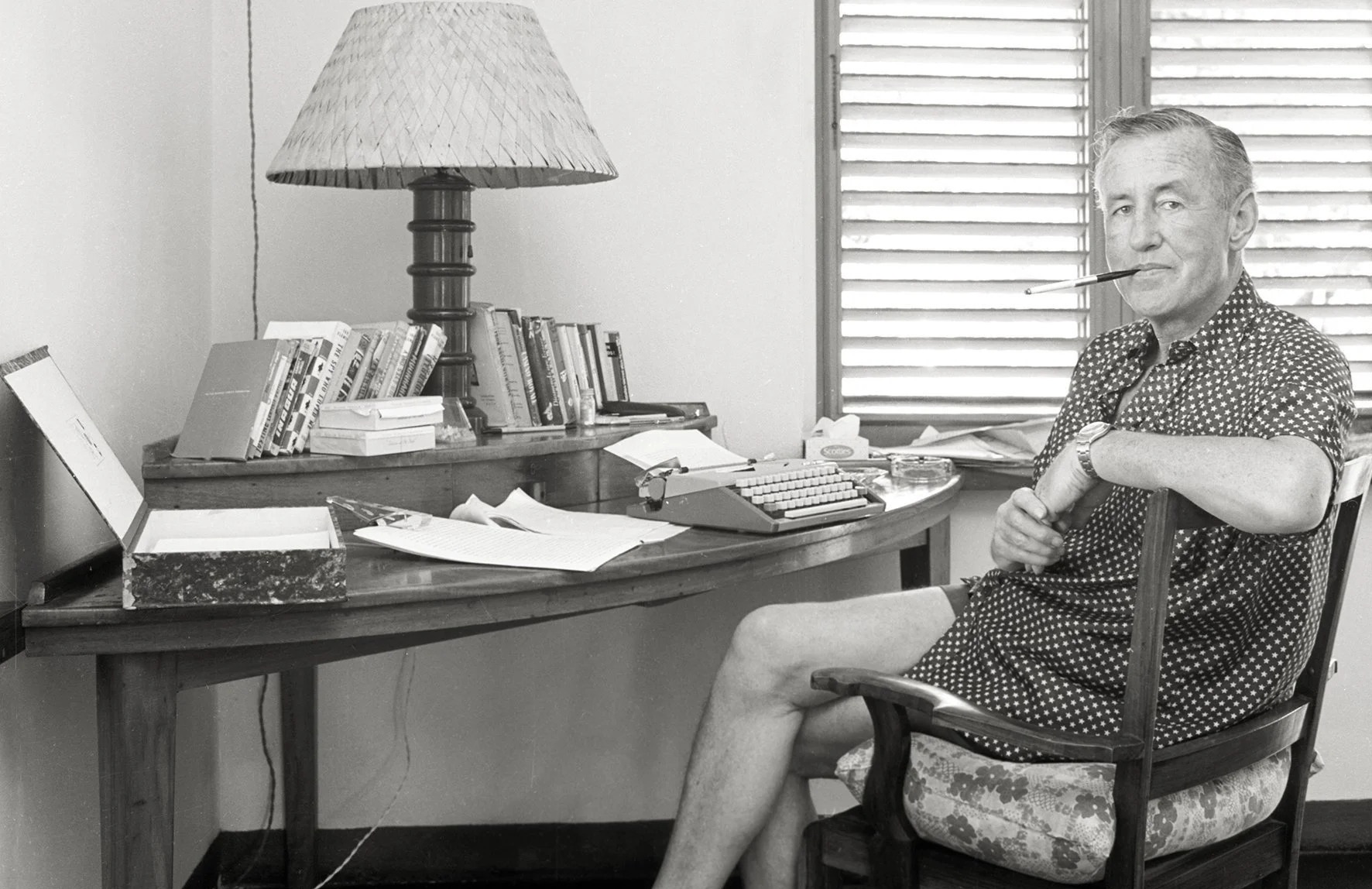

Ian Fleming at his Goldeneye estate in Jamaica

Published in 1961, Fleming’s novel included elements that McClory and Whittingham felt they had created, but they did not see any acknowledgment in his book. They took Fleming to court.

The case lasted a few years, apparently longer than Whittingham could hold out because of the continuing legal fees he could no longer afford. In 1964, before a legal decision was made, Fleming decided to settle out of court. He was in ill health and no longer wanted to continue fighting. He agreed to let McClory have the rights for a film version of Thunderball. Fleming died a few months later.

In the years before his death, though, Eon Productions had the rights from Fleming to adapt his other novels to motion pictures. (Casino Royale was an exception because the rights already belonged to producer Charles K. Feldman.)

The partners of Eon Productions, Harry Saltzman (left) and Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli (right).

The Bond movies were not only important properties for Eon, Dr. No (1962), From Russia With Love (1963), and Goldfinger (1964) had been box office bonanzas.

Following Goldfinger, the next Bond film was originally planned to be On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. However, around that time, Kevin McClory told the press that he was about to go ahead with his plan to film Thunderball and that Richard Burton would possibly star.

Broccoli and Saltzman felt it was bad enough there were so many imitations to the Bond films (an estimate in 1965 amounted to approximately 50), they did not need people being confused by a separate 007 movie. In addition to that, they had always wanted their first Bond movie to have been Thunderball and had screenwriter Richard Maibaum write a script based on the book. But then the McClory/Whittingham lawsuit happened and the film was put on hold. Dr. No was chosen instead to be the first.

Robert McGinnis’ original painting went for $275,000, including buyer’s premium, through Heritage Auctions in 2022.

Something had to be done before McClory went ahead with Thunderball. And this is where the old saying comes in, “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.” Broccoli, Saltzman, and McClory made a deal that Eon Productions would make the film and McClory would be credited as “Producer,” plus receive 20% of the gross. In return, McClory agreed to not make a film based on Thunderball until 10 years after the release of Eon’s. (It’s been said that Cubby and Harry felt the Bond market would have started to dwindle by that time.)

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was put on hold and Thunderball was made the next in line. Richard Maibaum was brought back to rewrite his script (with British playwright John Hopkins brought in later to polish it and add quips for Bond.).

While everything was now good regarding making the film, there was another front involving Thunderball that had tempers flaring.

—

2. THE THUNDERBALL COMIC STRIP

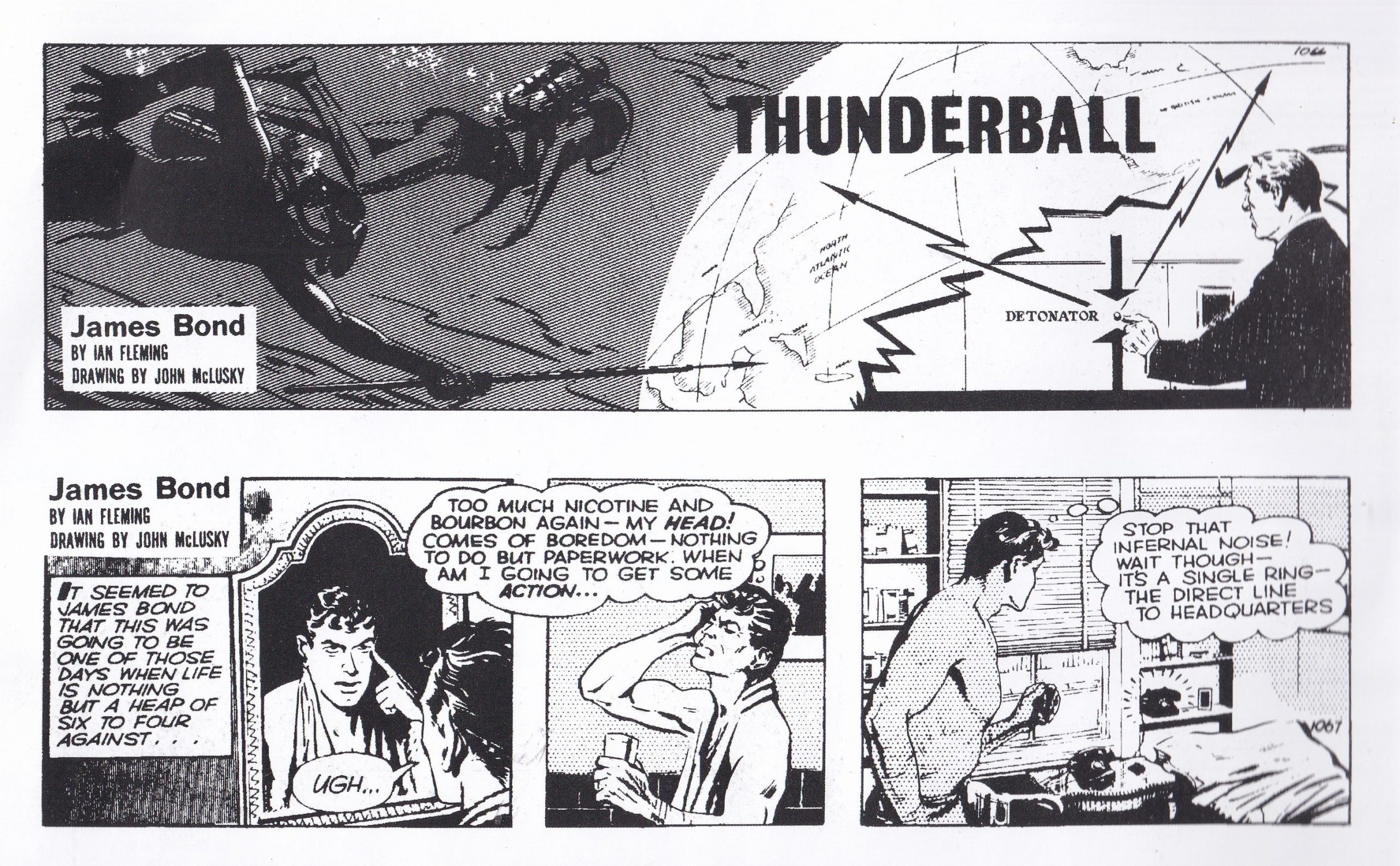

Since 1958, a James Bond comic strip had been appearing in the United Kingdom’s Daily Express newspaper, with each adventure an adaptation of a Fleming novel or short story. Thunderball was the 10th story adaptation and it all started out fine December 11, 1961…

First two days of the Thunderball strip adaptation (#1066, December 11, 1961 and #1067, December 12, 1961). Script: Henry Gammidge. Art: John McLusky.

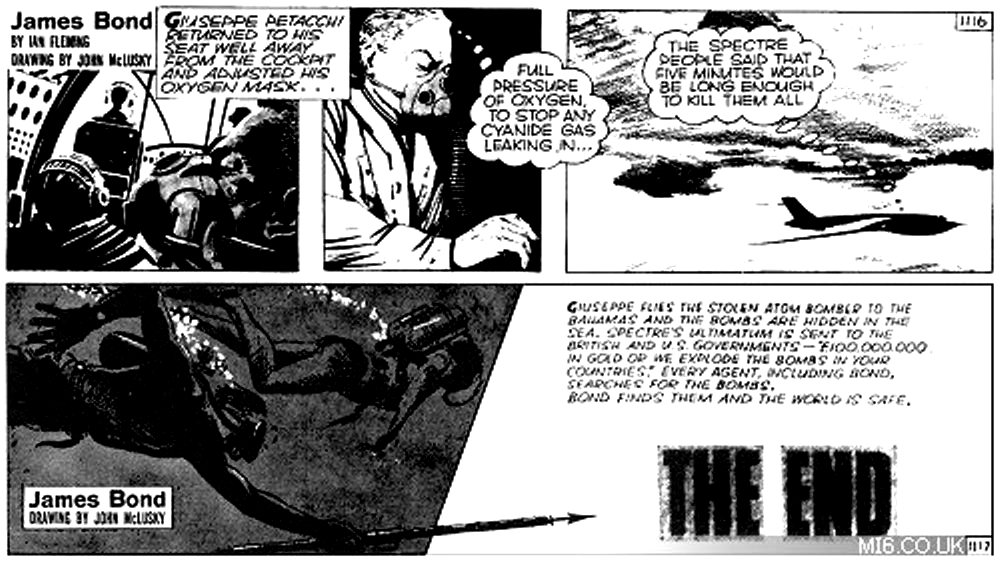

…but it came to a very quick and completely unexpected end a couple months later. Most of the story was still to come but it was wrapped up in one strip:

The final two strips printed of the Thunderball story in the Daily Express. It went from the normal February 9, 1962 storyline (above, #1116) to its immediate cancellation the next day (#1117, which even re-used the first strip’s title artwork again). Script: Gammidge. Art: McLusky.

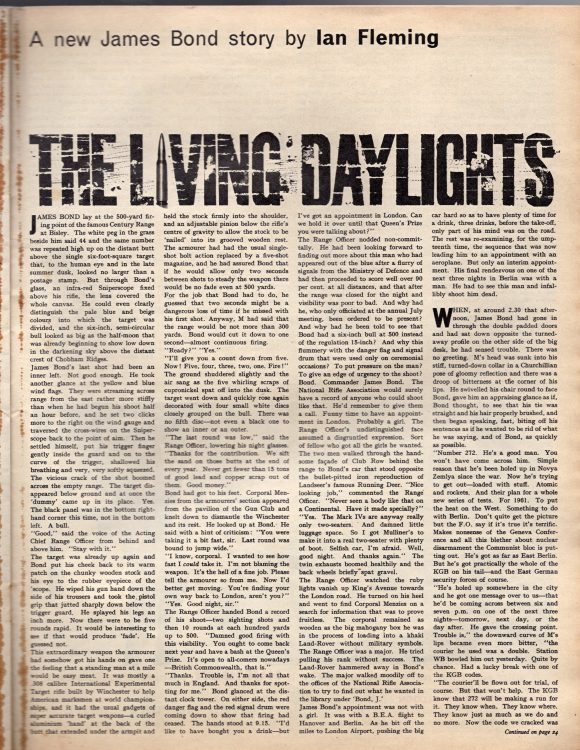

What had happened was that Fleming had sold his new James Bond short story, The Living Daylights, to the UK’s Sunday Times Magazine for its debut issue of February 4, 1962.

Fleming’s short story The Living Daylights in The Sunday Times Magazine, February 4, 1962.

This enraged Lord Beaverbrook, owner and publisher of the Daily Express, because the Sunday Times was a competitor. Beaverbrook ordered the strip to be discontinued, which he had the power to do because he had purchased the rights to adapt Fleming’s stories into a comic strip. (For the syndicated newspapers, however, a few more strips were added to wrap up the strip quickly, but again with the bulk of the story untold.) It would take almost three years before Beaverbrook allowed the strip back in the Express (adapting On Her Majesty’s Secret Service beginning June 29, 1964).

—

3. BEHIND THE SCENES OF THUNDERBALL

Every Bond film is only as good as the team of professional craftspeople working off-camera. Returning for the fourth Bond film was the best team ever, proving “Nobody does it better.” (OK, OK, I know that song is from The Spy Who Loved Me, but it was true about the Thunderball gang.)

(NOTE: All video clips below are © Amazon MGM Studios)

Terence Young – the director of Dr. No and From Russia With Love (1963).

Director Terence Young (left) and screenwriter Richard Maibaum (right)

Richard Maibaum – In all, Maibaum wrote or co-wrote 13 Bond film scripts, starting with Dr. No and ending with License to Kill (1989).

Maurice Binder – Binder worked on 16 Bond movies. With Thunderball, he transformed the title sequence forever going forward by adding nude women into the imagery.

Ted Moore – the cinematographer who shot the first three films, as well as Thunderball, and then Diamonds Are Forever (1971), Live and Let Die (1973), and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974).

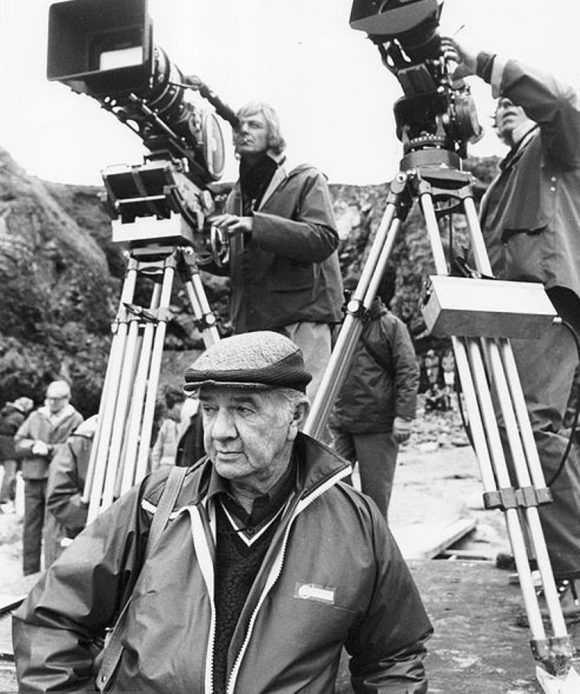

Cinematographer Ted Moore.

Peter R. Hunt – Hunt’s role as film editor started with Dr. No, and continued through Thunderball. However, with the latter, he proved to be way beyond valuable to Broccoli and Saltzman. Terence Young had left after the filming of Thunderball was done… and the rough cut was over four hours long! Hunt cut it down to just over two hours. In return for this, he was made second unit director of You Only Live Twice (1967) and then director of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969).

Ken Adam – the amazing production designer of Dr. No and Goldfinger was given a new challenge with Thunderball. In addition to creating a number of amazing sets for the film, he was called upon to do the same for the underwater sequences… of which there were plenty. To this end, he designed the Disco Volante, the underwater bomb carrier, and the towing vehicles. Following Thunderball, he worked on You Only Live Twice, Diamonds Are Forever, The Spy Who Loved Me, and Moonraker.

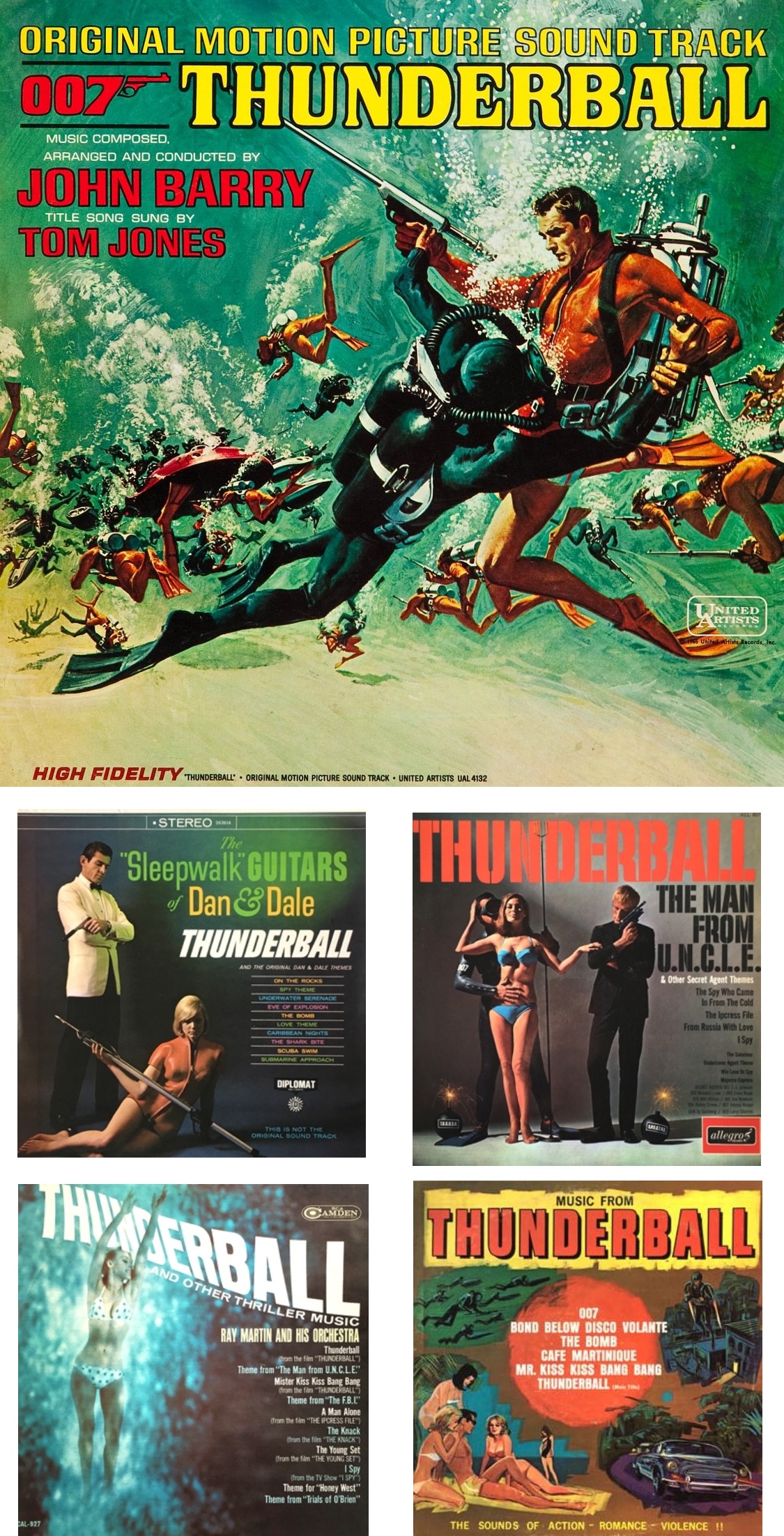

John Barry – It’s impossible to think of the early Bond movies without Barry’s dynamic scores (11 in total). And, for Thunderball, he had to pull off a last-minute miracle. The song for the film’s opening credits was set to be Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (a reporter’s nickname for Bond), with lyrics by Leslie Bricusse. It was recorded by Shirley (Goldfinger) Bassey, as well as by Dionne Warwick.

Shirley Bassey’s version:

Dionne Warwick’s version:

However, just before the film’s release, United Artists said the song must be titled “Thunderball” so that each time it was played by radio stations it would generate more public interest in seeing the movie. So, Barry and lyricist Don Black dashed out “Thunderball,” which was sung by Tom Jones. (It is said that after he sang the very extended last syllable in the final lyric, “So he strikes like Thun – der – BALLLLLL!”…Jones passed out.)

Oh, there was one other song created for the film — and not by Barry. It was submitted by Johnny Cash to the producers but never used:

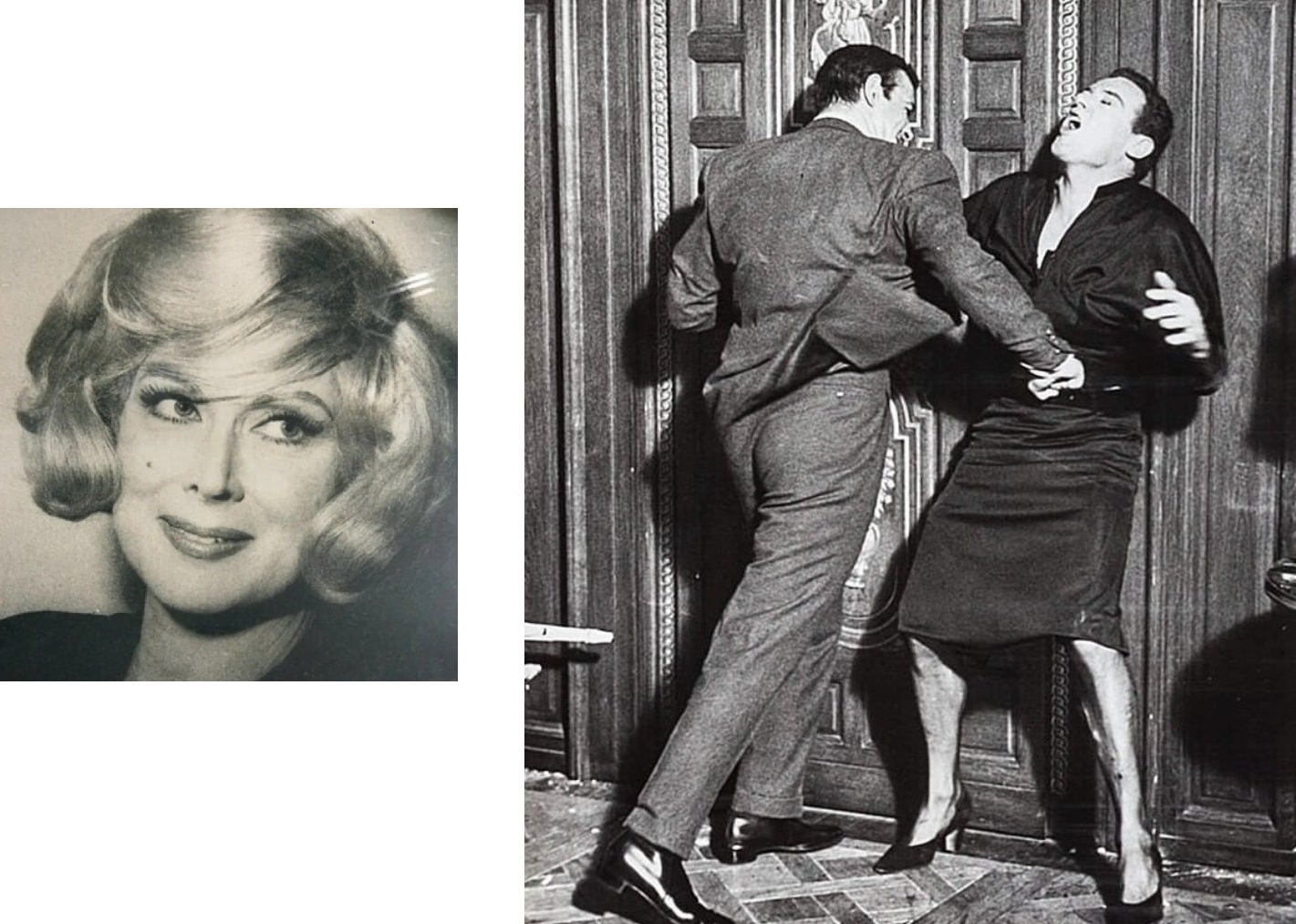

Bob Simmons – In addition to being the stunt double for Sean Connery, Simmons also had an uncredited role in Thunderball as Colonel Jacques Bouvar, but disguised as his widow. (Until the fight started, Bouvar was played by Rose Alba.) (The character was listed incorrectly in the end credits as “Madame Boitier.”) Simmons arranged the fights for a number of the Bond films with Connery and Roger Moore.

The widow before (Rose Alba) and the “widow” after (Bob Simmons).

—

4. THE CAST

James Bond. Returning to the screen was Sean Connery as Bond, but he was not happy about it, feeling he was becoming only identified as just 007 and not acknowledged for his other roles in movies. He also felt he was not being compensated enough for making the series as popular as it was.

Bond’s returning allies:

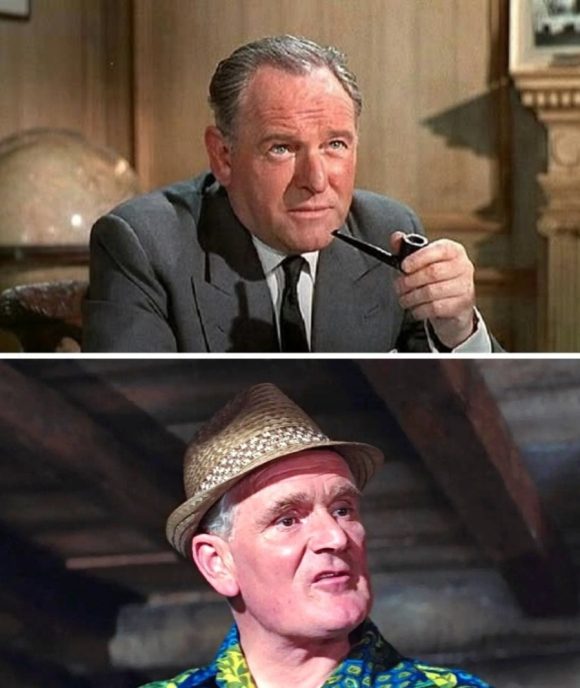

M – With Thunderball, Bernard Lee made his fourth of 11 appearances as Bond’s boss in the British Secret Service.

Bernard Lee (top) and Desmond Llewelyn (bottom)

Q – And it would not be a Bond movie without Q providing new gadgetry for 007. Desmond Llewelyn appeared in 17 James Bond movies, making him the champion.

Miss Moneypenny – Lois Maxwell, as the ever faithful and reliable Moneypenny, also returned in her fourth of 14 Bond films.

Felix Leiter – Rik Van Nutter became the third actor to undertake the role of CIA agent Felix Leiter on the big screen (the character was not in From Russia With Love). His wife at the time was Swedish actress Anita Ekberg, who had co-starred with Bob Hope in the 1963 Broccoli-Saltzman film, Call Me Bwana. (Remember that huge Call Me Bwana movie poster on the side of the building with Ekberg’s face – and mouth — in From Russia With Love?)

March 1965 news photo of Anita Ekberg and Rik Van Nutter at London Airport, captioned, “Anita flew in from Rome for a holiday with Rick, who has been filming in the latest James Bond film, ‘Thunderball’.”

The Bond Women:

The “Bond Girls” of Thunderball. Left to right: Lois Maxwell, Luciana Paluzzi, Martine Beswick, Sean Connery, Claudine Auger, and Mollie (Molly) Peters.

Patricia Fearing – Mollie Peters (credited as Molly Peters) made a memorable turn as Bond’s physiotherapist but her voice was dubbed by Barbara Jefford. (Jefford also provided the voices for Daniela Bianchi in From Russia With Love and Caroline Munro in The Spy Who Loved Me.)

Domino Derval – Raquel Welch had been hired to play the role but Richard Zanuck, the head of production at 20th Century-Fox, asked the producers for her release because he needed her for Fantastic Voyage (1966). Julie Christie was also considered. Claudine Auger, who got the role, was a former Miss France. However, because of her accent, she was dubbed by Nikki van der Zyl, who provided the voices for actresses in 11 Bond films.

Paula Caplan – Martine Beswick, who had been one of the batting gypsy women in From Russia With Love, returned to the Bond films in the role of his fellow agent. While we don’t know if Paula was a lover of 007’s, Beswick was considered a “Bond Girl” by the press.

Bond’s Enemies:

Ernst Stavro Blofeld – So, who was the mysterious actor that played Blofeld (called “No. 1”) in both From Russia With Love and Thunderball?

Look to Dr. No if you want to see his face. Anthony Dawson appeared in that film as the quisling Professor Dent (the guy with the tarantula). The voice of No. 1, however, was that of Eric Pohlmann in both From Russia With Love and Thunderball.

Blofeld revealed! Anthony Dawson (left) and Eric Pohlmann (right)

Emilio Largo – Adolfo Celi played SPECTRE’s No. 2 man, Emilio Largo, the instigator of the plot to steal the two nuclear missiles in Thunderball. (By the way, if you ever wondered what “Thunderball” meant, it was an unofficial military term for the mushroom cloud from an atomic or nuclear explosion.)

Don’t worry, Adolfo, Robert Wagner doesn’t hold a patch on you.

Celi’s voice was also dubbed in Thunderball.

A video clip of Celi and Auger before and after being dubbed (by Robert Riettio and Nikki van der Zyl, respectively).

Fiona Volpe – Luciana Paluzzi had previously worked with director Terence Young in a 1958 movie called, coincidentally, No Time to Die and she auditioned for the role of Domino. Young called her later to say she did not get the part… but she was being cast as SPECTRE’s master assassin (a role that a number of Bond fans think was much better).

—

5. LOCATIONS

Filming began February 16, 1965 at the Chateau d’Anet in France for the sequences involving the chapel funeral, the fight inside Colonel Bouvar’s home, and the rocket pack escape. (Filming there was tied into Connery being available at the time, as he was in Paris to attend the opening of Goldfinger.)

Kevin McClory was determined to earn his screen credit of “Produced by.” His home was in the Bahamas where most of the Thunderball production was to be filmed, and he did much of the location scouting himself. He also secured the cooperation of many local officials to film there and enlisted his well-to-do socialite neighbors to appear as extras in various scenes.

—

6. THE OPENING

The gun barrel sequence at the start of Thunderball was a familiar sight but this time it had Sean Connery as Bond. Before this, it had been Bob Simmons (which, in effect, makes him the very first big-screen James Bond).

—

7. GADGETS AND STUNTS

The jet pack in the opening sequence was from Bell-Textron Aerosystems and the flight was done by Bill Suitor and Gordon Yeager (no relation to Chuck Yeager). It was a dangerous stunt because the jet pack could fly for only 21 seconds and then ran out of fuel. Before Suitor and Yeager were brought in to do the flight, Terence Young went ahead and shot close-ups of Connery “flying.” When they did arrive to do their flights, Suitor insisted on wearing a protective helmet. Connery had to be re-filmed later wearing the helmet in order to match up the shots.

Here’s footage of Suitor 20 years later at the 1984 Olympics held in Los Angeles:

One other memorable moment of the film’s pre-title sequence was the astonishing amount of water shot out from the rear of the Aston Martin DB5 at the enemy agents. The actual car would never have been able to hold so much water, no matter how rigged it was, so it was accomplished by having huge hoses placed under the vehicle.

One of the very best stunts in the film had Count Lippe pursuing Bond’s car to kill him, but Lippe was then blown up by missiles from the B.S.A. Lightning motorcycle ridden by Fiona Volpe. How it was accomplished is shown in this section of a Ford Motor Company short filmed on location:

—

8. THE HUNT FOR BOND

Junkanoo, the parade in the Bahamas in which Bond tries to hide in order to escape from Fiona and her men, was specially recreated for the film. The real Junkanoo parades are held on the day after Christmas and on New Year’s Day. For the movie, though, it was staged over Easter for two days in Nassau with Terence Young having the parade go around and around the area so he could film the excitement of it as it was happening, rather than stopping the parade for individual shots.

—

9. THE UNDERSEA FILMING

Claudine Auger was doubled in her undersea swimming scenes by Evelyne Boren, the wife of Lamar Boren, Thunderball’s underwater cameraman, who had served in that capacity on two TV series, Sea Hunt and Flipper.

The exciting climactic aqua-parachute drop was made by members of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary and was filmed by André de Toth (the director of the 1953 3D cult film, House of Wax). The underwater film director was Ricou Browning, who had played the Gill Man in Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and its two follow-up features. (Browning also co-created the Flipper TV series.)

—

10. COLONEL CHARLES RUSSHON

Retired USAF Lt. Colonel Charles Russhon was a technical military adviser and liaison for several James Bond motion pictures. He was instrumental in the filming of Goldfinger by obtaining permission to fly over the restricted airspace of Fort Knox. For Thunderball, he helped to secure the jet pack for the opening sequence, as well as getting $92,000 worth of free underwater gear.

Retired Lt. Col. Charles Russhon played a military officer (center) in Thunderball.

For the final scene in the film, Russhon arranged for the borrowing of the Fulton Skyhook (as well as the B-17 plane and flight crew) that rescues Bond and Domino.

—

11. THE FILM’S RELEASE

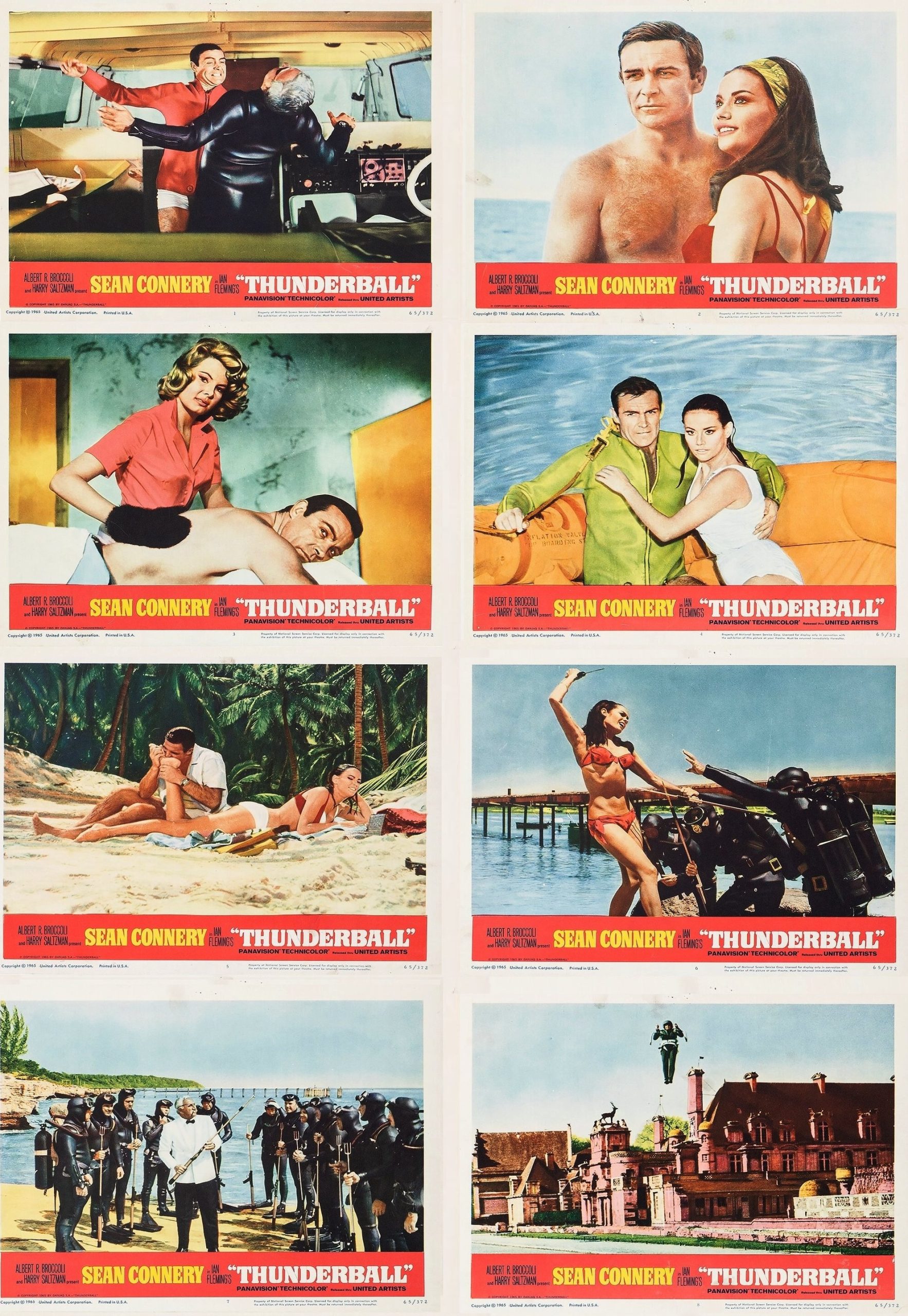

Original 1965 set of 8 lobby cards

The world premiere of the film was in Tokyo on December 9, 1965. The U.S. debut was 12 days later, on December 21, and it opened wide on the 22nd. (The London premiere was December 29.)

Writing in The New York Times the day after the New York opening, film reviewer Bosley Crowther said, “The popular image of James Bond as the man who has everything, already magnificently developed in three progressively more compelling films, is now being cheerfully expanded beyond any possible chance of doubt in this latest and most handsome screen rendering of an Ian Fleming novel, ‘Thunderball.’”

Crowther continued, “Now Mr. Fleming’s superhero, still performed by Sean Connery and guided through this adventure by the director of the first two, Terence Young, has not only power over women, miraculous physical reserves, skill in perilous maneuvers and knowledge of all things great and small, but he also has a much better sense of humor than he has shown in previous films. And this is the secret ingredient that makes ‘Thunderball’ the best of the lot.”

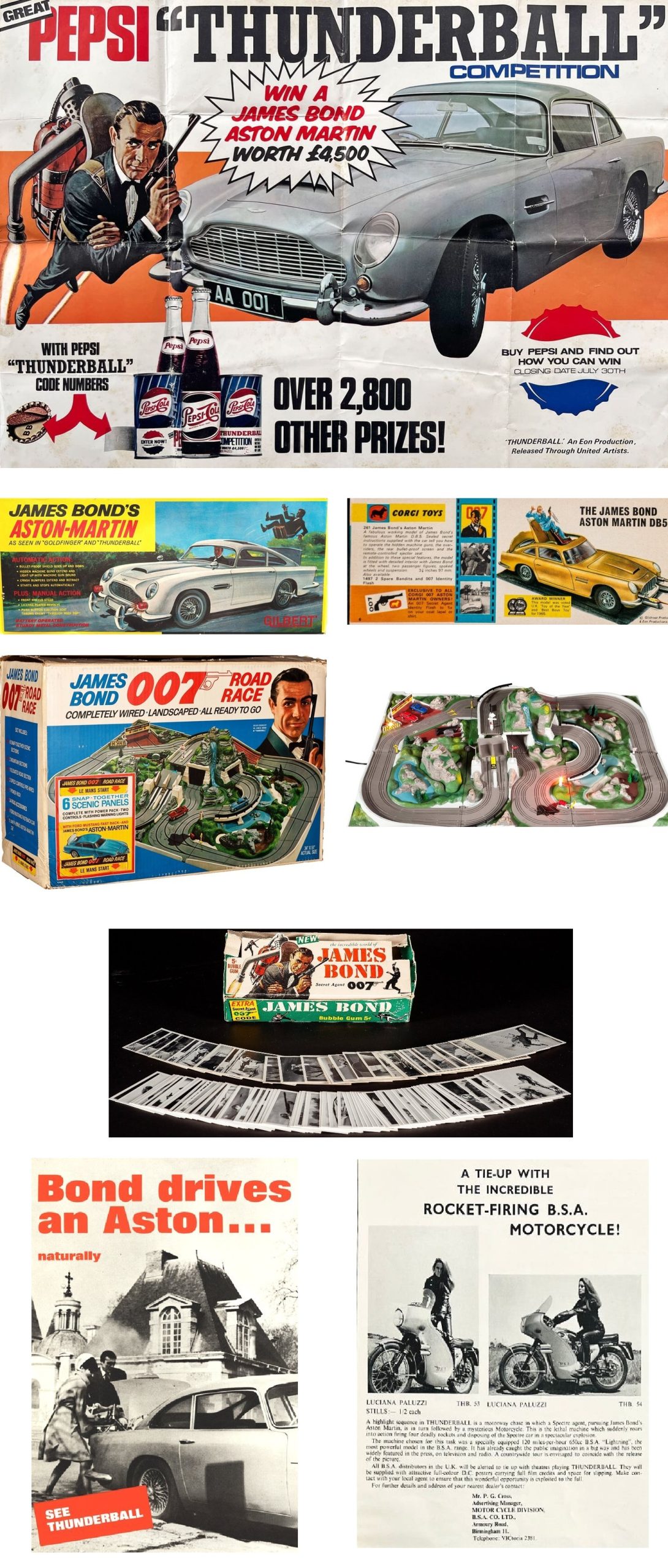

While great reviews are wonderful, just how much business did it do? Out of all the Bond films to date (including the separate version of Casino Royale in 1967 and Never Say Never Again in 1983), the highest-grossing remains Thunderball at more than $1.4 billion (with domestic and international box office receipts adjusted for inflation). And that’s not even taking into account the merchandising!

—

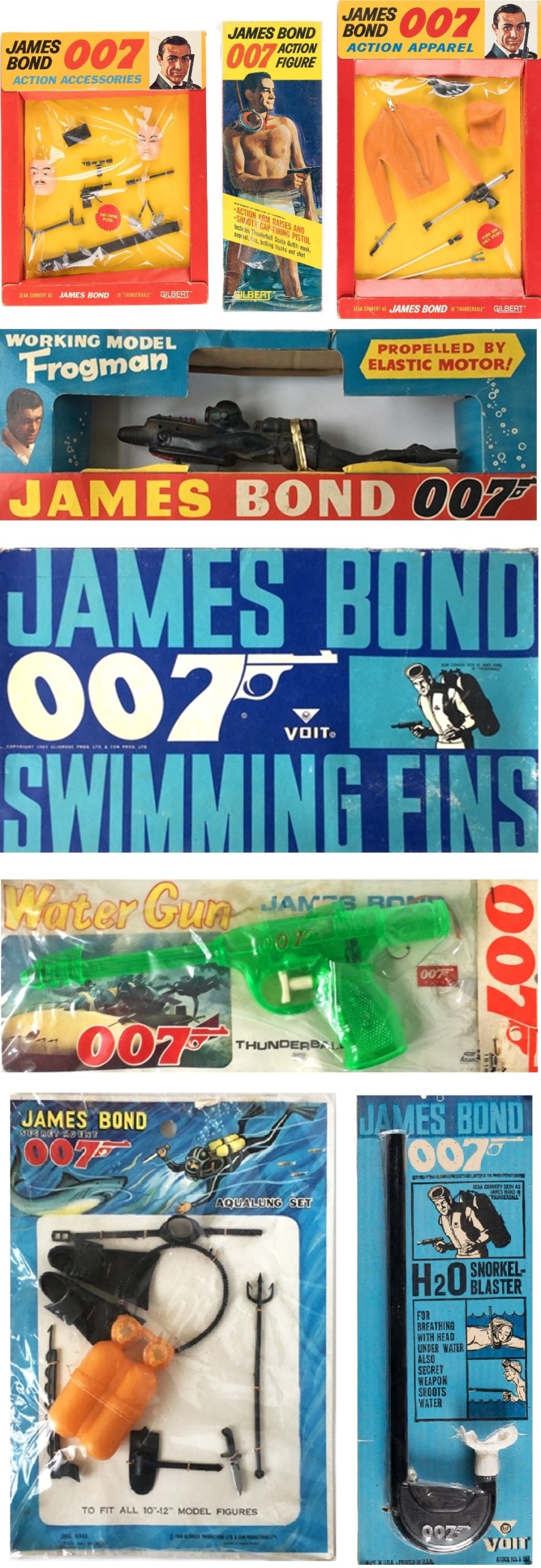

12. MERCHANDISING

They say a picture’s worth a thousand words. If that’s so, here’s a whole dictionary. (And this is a just a miniscule amount of all the items released to tie in to Thunderball.)

—

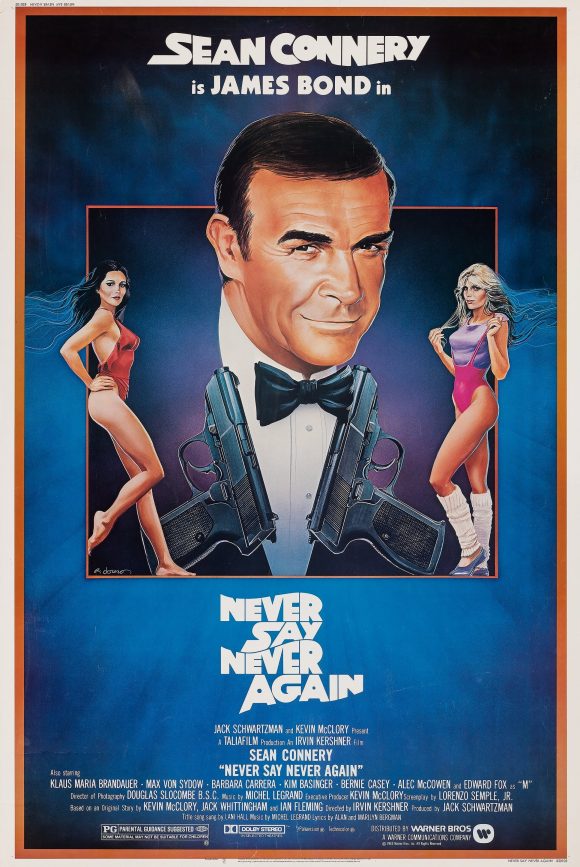

13. NEVER SAY NEVER AGAIN

Of course, Kevin McClory did get to finally make his version of the Thunderball novel: Never Say Never Again (1983), which got the bonus of having Sean Connery starring. As most know, the title came from Connery saying “never again” about playing Bond after Diamonds Are Forever. However, the money was too good to pass up. (It is estimated he received, with salary and his percentage of the gross combined, $86.5 million.) Ricou Browning, who had been the underwater filming director of Thunderball, also directed the underwater action for the new film.

Poster art by Rudy Obrero

—

One last item…

On April 18, 1966, John Stears won an Oscar for the special visual effects of Thunderball. Twelve years later, he won his second Academy Award (as did John Dykstra, Richard Edlund, Grant McCune and Robert Blalack) in the same category for — Star Wars!

As I said earlier…

—

MORE

— JAMES BOND ON SCREEN: 13 Essential Elements of 007 Introduced in DR. NO. Click here.

— 13 GREAT POSTERS: A SEAN CONNERY Salute. Click here.

—

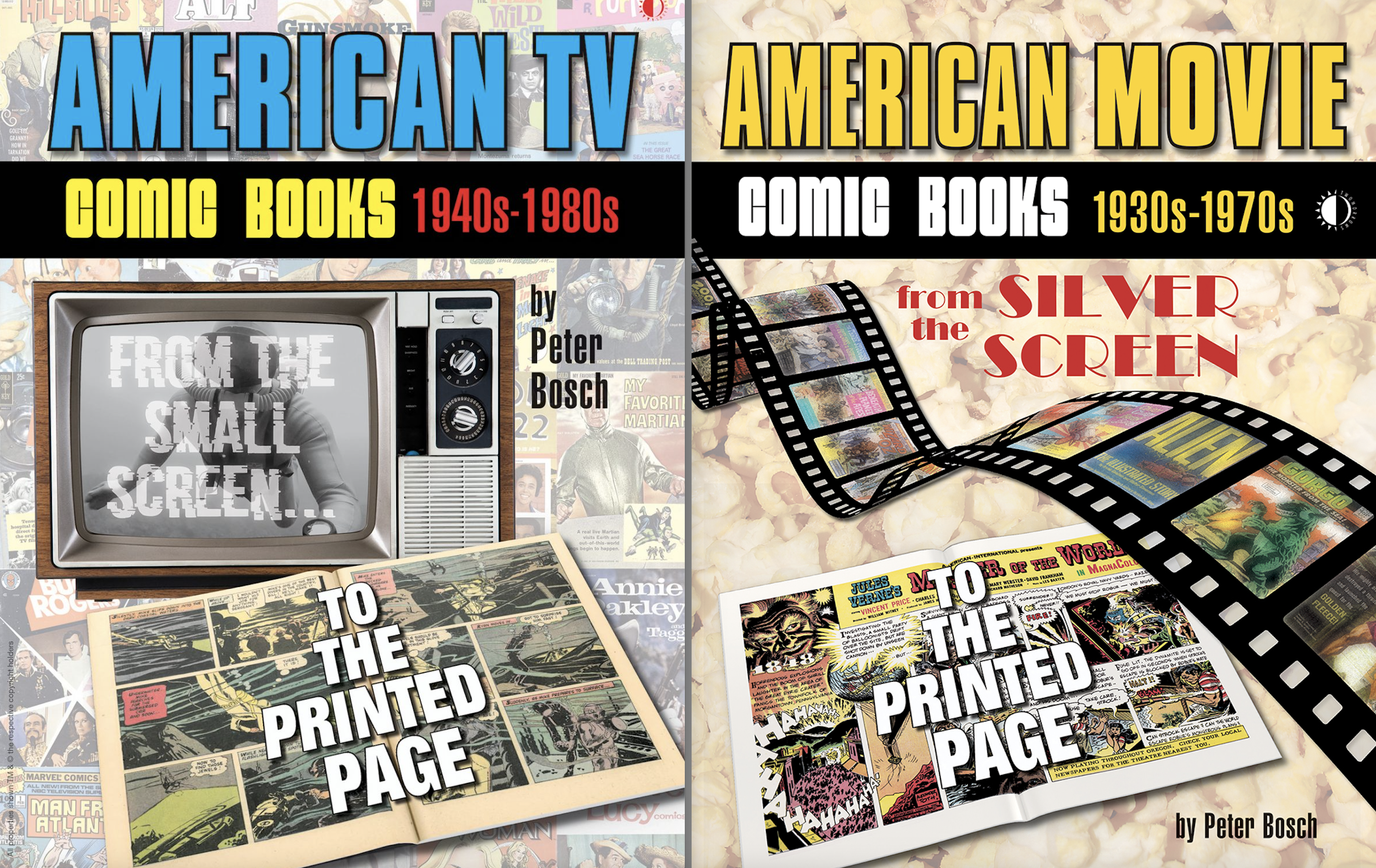

13th Dimension contributor-at-large PETER BOSCH’s first book, American TV Comic Books: 1940s-1980s – From the Small Screen to the Printed Page, was published by TwoMorrows. (You can buy it here.) A sequel, American Movie Comic Books: 1930s-1970s — From the Silver Screen to the Printed Page, is out now. (Buy it here.) Peter has written articles and conducted celebrity interviews for various magazines and newspapers. He also writes the FOUR COLOR RADIO column for 13th Dimension. Peter lives in Hollywood.

December 21, 2025

That Johnny Cash song is both totally awesome and completely wrong for a James Bond movie all at once.

December 21, 2025

Precisely.

December 21, 2025

2006’s Casino Royale was a masterpiece, but Thunderball’s my personal favorite Bond movie of them all.

December 21, 2025

Thanks Peter. I thought I knew every piece of trivia about my favorite James Bond film, but I am happy to have learned even more! I think I first saw Thunderball as a ABC Sunday Night movie during Christmas break in 1978 or ‘79. No school the next day so my parents let me stay up. I was mesmerized and committed all of the best parts to memory (we wouldn’t get a VCR for another 5 years).

December 22, 2025

Brilliant article and my favourite Bond film too! Thank you.

December 26, 2025

Thunderball is a still-impressive spectacle and remains a classic. The most common criticism of the film is that the underwater sequences go on too long, but that has never bothered me. But I do feel Thunderball marks the point where the Bond series began to be overwhelmed by gadgetry and gimmicry, at the expense of elements such as characterization. Largo is a pretty dull villain, whereas in the book he’s younger and more of a dark mirror of Bond, a sensual, ruthless ladykiller. Similarly, movie Domino, while very beautiful, is a pale reflection of Fleming’s, who was far more fiery and passionate. In the book you really got the sense that Bond had fallen in love with her, whereas in the film it’s just another fling. All that said, Thunderball is still one of the best entries in the Bond series.