Joshua Hale Fialkov and Gabo of The Life After talk with G.D. Kennedy about their new arc from Oni Press. Issue #2 is out 12/16.

By G.D. KENNEDY

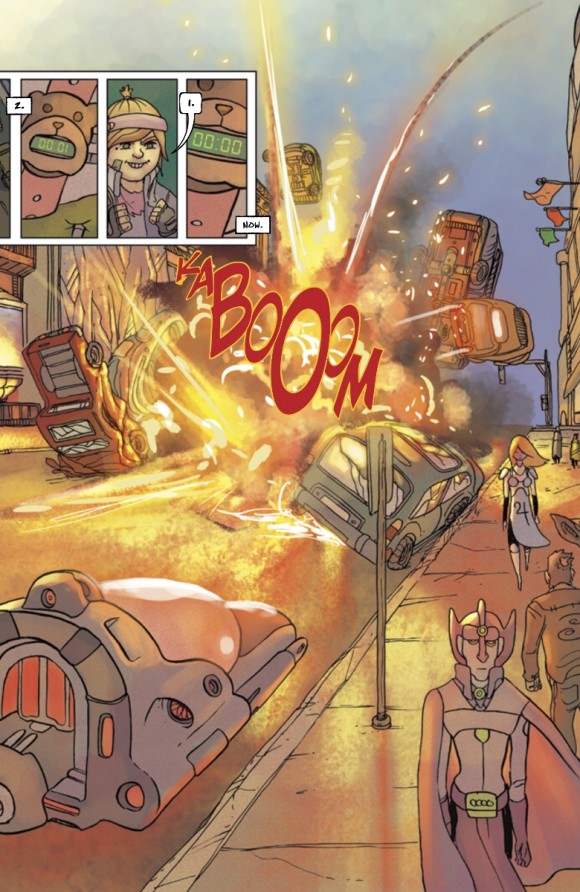

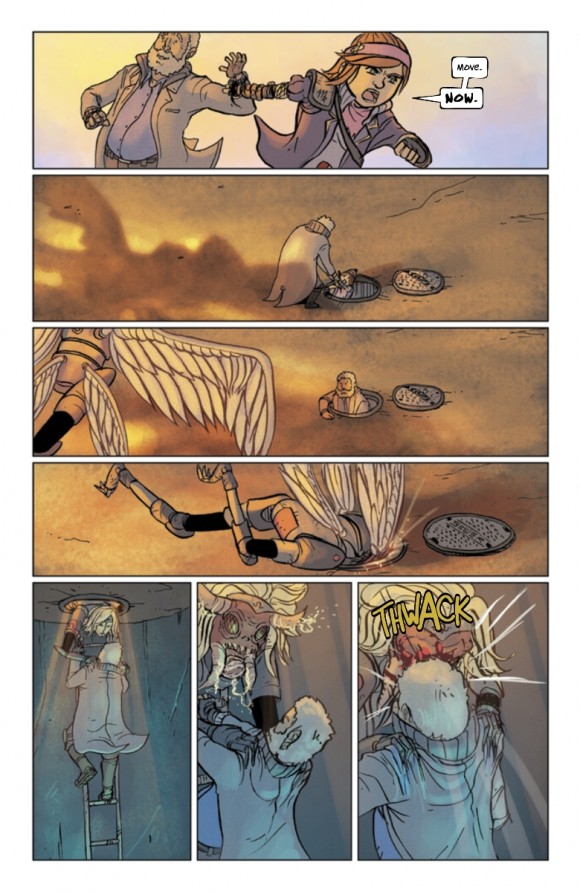

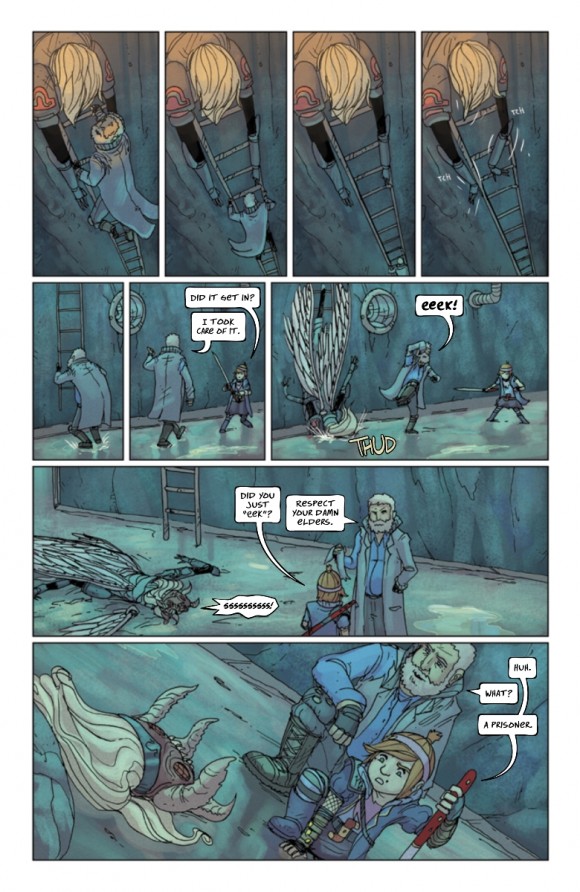

A swarm of ancient rabbit gods move on the armies of Heaven and Hell in a bid to save the second son of God and Ernest Hemingway, recent escapees from purgatory for suicides, from their impending advance. As bizarre as life may be, the afterlife is even weirder, or at least if you accept the version offered by writer Joshua Hale Fialkov and artist Gabriel Bautista, better known as Gabo.

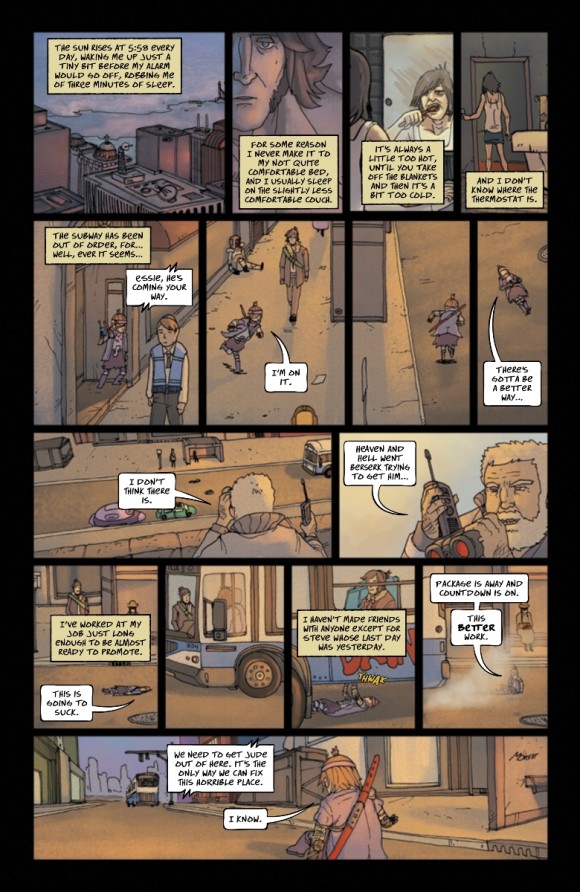

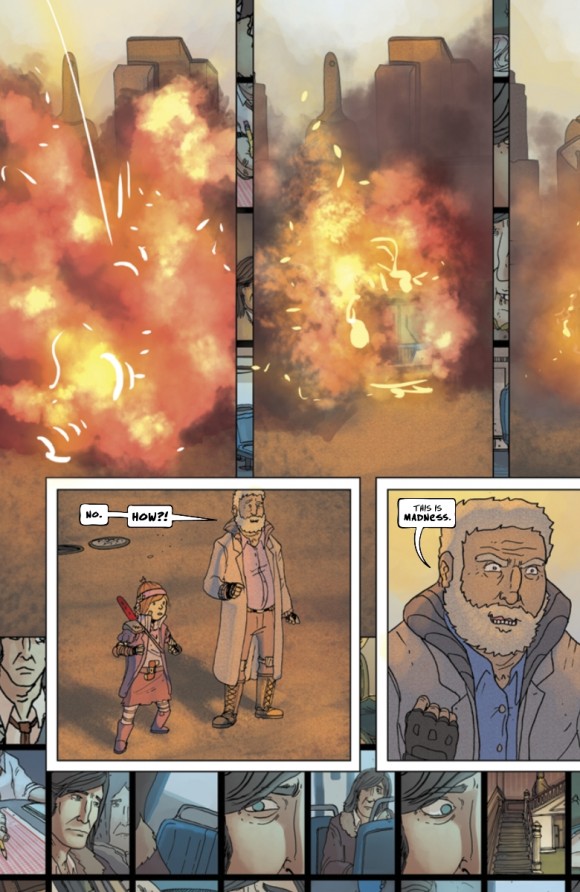

The Life After, Fialkov and Gabo’s series from Oni Press, is their exploration of what happens after we leave from this plane of existence — it is a wild tale, a mixture of surreal and absurd and dark and compelling, riddled with heavy doses of cynicism and humor, and buoyed by an underlying air of optimism. The series has embarked on its second chapter, titled The Life After: Exodus, in which protagonist and second-son Jude finds himself mired back in purgatory after his brief escape in the first chapter and, like before, his is living a constantly repeating day, suffering through some melancholic version of Groundhog’s Day, oblivious to the fact that he is in the afterlife, or that he is condemned to an eternity of repetitive doldrums. Much like the first arc, the book examines religion as a construct and the unity — and divides — between faiths, while also looking at religion’s conceptual evolution, and the balance between the chains of reality and the afterlife, always keeping its sense of levity but at the same time comfortable to depart into darker territories (if always with tongue planted somewhat in cheek).

We recently had the chance to pick Josh’s and Gabo’s brains about the afterlife, as well as The Life After, and here is what they had to say:

—

G.D. Kennedy: Can you just tell our readers a bit about what The Life After is about?

Joshua Hale Fialkov: The Life After is the story of a man [Jude] who woke up one morning to find himself living in the afterlife for suicides. He doesn’t remember killing himself. He doesn’t know why he’s there. He’s going to go and get answers anyway he can, alongside Ernest Hemingway, a Victorian lady named Nettie, and her daughter who is the leader of an army of unbaptized souls. So, just, y’know, your average post-modern darkly humorous religious adventure story for the sick and twisted.

G.D.: How did Life After come into being? Was this a collaborative process between the two of you?

Joshua: I’d been working on the idea in the different forms for a while, but when i met Gabo via our mutual friend Richard Starkings, I knew that I’d found my muse. Gabo’s imagination, storytelling chops, and, honestly, his sheer brilliance in every way has made this book something so much more than anything I could have ever imagined.

Gabo: The thing I love the most about Josh is that not only does he write amazing and easy to read scripts, but he also lets me unleash my fury on the book. He’s the rich uncle that throws me into a candy store and lets me consume anything I want. After 11 issues of this book we’re getting to the point where it’s just natural – he knows how to write for me now, so collaborating is about as natural as breathing air. WE ARE SYMBIOTIC.

G.D.: Purgatory in Life After is terrifying in that it not only that it is so painfully repetitive, but that the mundane elements of it so mirror the real-life day-to-day existence of many people that it is not even clear that purgatory is not reality. Why this take on purgatory? Is there something about this redundancy that you find particularly terrifying or true?

Gabo: It’s no surprise that this take on purgatory hits so close to home for so many people, everyone can see themselves in Jude’s shoes. Mostly everyone I know has suffered what Jude has, and its terrifying to think that a lot of people in this world will continue to be stuck in that cycle of working just to survive, and that the creativity and life of people is being destroyed by society. I hope people take Jude’s courage and apply to their own lives, break out of that cycle, chase after that dream you keep seeing on the bus!

Joshua: To some degree, it’s a bit more personal than it seems. I spent years of my life working production in TV and film, retail at video and record stores, and at some soul crushing office jobs. So much of my life was driven by surviving, by making sure I could pay rent and buy food, that I fell into the pattern of surviving rather than thriving. Deciding to chuck it all in order to be a writer and storyteller full time was terrifying and took away almost all of the comforts I’d taken for granted.

One of the most common things said to a comic book creator is, “How do I do what you do?” and usually that comes from that same place. Realizing that there’s something out there that’s better, that speaks to the heart’s desires, and knowing that if you just had the ability or the time or, in reality, the courage, maybe you could be doing it. That’s just a universal thing everyone goes through.

G.D.: The second volume, Exodus, takes Jude back to purgatory and the same routine he knew before. How did he end up back in suicides purgatory after Nettie killed him at the end of the first volume? Why did you decide to take Jude back?

Joshua: That’s just what life is, isn’t it? We fight and struggle to find something bigger and better out there, and yet, much of the time, we’re kicked in the shins and pushed out a moving car, to start back where we began. For Jude, finding out a bit more about who he is and why he’s there wasn’t enough. It’s going to take a lot more to win the game.

G.D.: What will Exodus explore that wasn’t examined in the first volume?

Joshua: Well, we’ve learned about the creation of the universe, the origin of this new group of people who are challenging the standards of the universe… Now, their only option is to get the hell out. But, there will be temptations that keep them from leaving. Including the reigns of the universe itself.

G.D.: Suicide is a central theme of this book, as the series opens in the purgatory for suicides, and Ernest Hemingway and Nettie both killed themselves. This obviously was not chosen lightly, so why the focus on suicide? What does it mean to the story, and to you personally as the creators

Joshua: I think suicide is one of the most misunderstood and maligned acts a person can take. It’s about one thing. Deep, seemingly unending pain. It’s a sickness. It’s a weakness, sure, but not one that should be judged. The way that judo-christian religions look at suicide has always offended me. It’s hypocritical. These people are in pain, and God claims to protect people, to save people, to end suffering, and yet, these people are sent to suffer eternally for doing exactly that. It bothers me. It’s unfair. And it stigmatizes something that if we just removed any sort of bullshit judgmentalness, could actually be prevented considerably more.

G.D.: There is a very real darkness to bits of this book. The two-page spread of traumatic infant deaths comes to mind, as well as the exploration of the various suicides. How has it been personally for you both working with these heady topics? Has the book’s levity been an attempt to counterbalance this?

Joshua: So much of it comes out of our conversations. Between Gabo and myself, as well as with Ari [Yarwood] and James [Lucas Jones], our book’s editors. We want to tell stories about something, and, to some degree, that’s about hypocrisy. The hypocrisy comes from both sides, and is almost always fouler than anything we can dream up.

Gabo: For that particular page on infant deaths, at first I refused to try and think up ways to kill kids. I figured I’d just go online and look up “dead baby jokes.” Turns out most of those jokes are way more disturbing than anything I drew for that issue. I had to find a balance between not too messed up and not too light, because I knew we had to drive the point home. I hope in the end people don’t just look at these pages as disturbing but a commentary on how messed up things are for people.

G.D.: Why is your God a floating, meaty potato? What has the reaction to this been? Have you received any backlash for depicting God in this fashion?

Joshua: We talked about it a lot when we were working on concept stuff. I think the idea that God is the amorphous entity that seems mostly harmless, but, at the same time has caused epic amount of suffering and destruction along the way. . . . Plus, it’s a bit of being a chicken on our point. No matter what form you make God, especially if it’s human, you get criticized for gender or race or nationality and so on. Making him a cosmic potato, while obviously, y’know, offensive, steers us away from the other actually offensive stuff.

Gabo: I think when people start reading this book, the idea that we’re dissing any sort of religion sort of goes out the window once they realize God is a meat sac. I tried my best to stay away from using any religious symbolism and just started building a more ancient and symbol based reality. I hope that the use of the Omega symbol and various astrological signs have helped to make this world its own twisted version of the after life.

G.D.: The reigning God in Life After is vey much a monotheistic Judeo-Christian God. Will we see any Hindu gods or deities from other current religions? How do they fit into your mythology for Life After?

Joshua: Oh, we do! One of our characters from the 2nd TPB on has been Ometochotli, who’s the ancient Aztec God of Alcohol. We actually have a scene where we find out how exactly he managed to be the only old God who’s survived. But, we’ve Ganeesha in there, a Coyote, and Ra.

Gabo: I like that fact that we’ve been able to take those other gods and insert them into this world, as they were once a big happy family or company of workers who ran things.

G.D.: Structurally, your concepts of Heaven, Hell and purgatory that you have created are fascinating in how fluid and ever-changing they are geographically. How did you two come to envision this as your setting?

Joshua: So much of that is Gabo and his imagination. I think I just described it as a mash up of time periods and cultures throughout time and space. But he’s the one who makes it so damn amazing.

Gabo: Again, Josh has given me just enough of a push in the right direction to start creating this world. A lot of what happens in the world though comes to me as I draw it, or color it even. The use of color has been very important to building the world. In heaven everything has a very cold blue fluorescent look to it, and in hell everything is warm and orange. So when you get one of the managers of hell showing up in heaven, he retains his orange tint, and vice versa. This book has literally been a sandbox for everything I’ve ever wanted to do, and Josh has absolutely no problem with me going nuts — haha.

G.D.: In Life After, there is a very real question as to who holds the moral high ground between Heaven and Hell, and even how one comes to hold the “superior” position, as God has only come to reign through violent force. Why approach the these as morally ambiguous rather than binary constructs?

Joshua: I’m a moral relativist at heart. I think that you can portend to have any goal or belief structure you want, but only through your actions does it actually matter. Having had plenty of conversations with, for example, Jews who hate Muslims, or Christians who hate homosexuals, has made me sick of the sort of binary us/them dynamic that rules so much of our lives. And, look, I’m just as guilty as anyone of being tied to that. We all are. But, the point of art is not to hold up a 1 to 1 mirror. But to hold up a funhouse mirror that allows you to make your point through distortion. That’s what so much of the Life After allows me to do.

G.D.: Has spending so much time exploring religious beliefs affected your own views on the afterlife or religion? How so?

Joshua: I don’t know that my opinions changed so much as I’ve become more open to other people’s beliefs. I think there’s the angry young man still buried inside that thinks that religion is stupid. But, seeing how this book has touched people and made people have conversations about faith and morality, and, most importantly, to laugh, has been really heart warming.

Gabo: I was born Catholic and turned Christian before I turned twenty. When I say Christian though, it’s a pretty loose version of Christianity. Since my early 20s I’ve lived by one ethic and that has been “don’t be an asshole.” So when Josh came to me and we started talking about this project and he expressed the same exact idea, I knew I was sold on this book. I’ve met a lot of readers that are religious, if not faithful and they all get what the book is trying to express, we all want the same thing- happiness.

G.D.: You are running a contest for fans to become a part of Life After, where three fans will be selected to be drawn into the comic. What is the contest? Whose idea was it and what brought it about at this time?

Joshua: Pure Gabo. He’s made such a big effort to get new readers and introduce the book to as many different people as possible, and, this one is all his.

Gabo: The contest at this point is over, but I feel we’ll end up doing it again in the future. Basically you take a picture of yourself with the issue, be it a floppy or an ipad, and the winners get drawn into a future issue of the book. To be fair though, I read an article where a guy did the same thing to boost his sales, but in my case, I just love drawing friends and random people into my comics. I’ve always loved seeing easter eggs like that in comics, and for me not to continue a tradition like that, well that seems silly.

December 8, 2015

Great interview! I wish I could explain with words how proud of you I am. You’ve come a long way and it’s only going to get better from here on out.