Visionary DC editor Julius Schwartz was born 104 years ago today…

—

UPDATED 6/19/19: Visionary DC editor Julius Schwartz was born 104 years ago on this date. (He died in 2004.) Seems like a great time to trot this one out again. Cool stuff. — Dan

—

In 2000, I was on my Great Comic Book Hiatus, a roughly 10-year sojourn in the wilderness of burnout and disinterest.

The reasons are unimportant right now, just suffice it to say that I thought comics were permanently in my past.

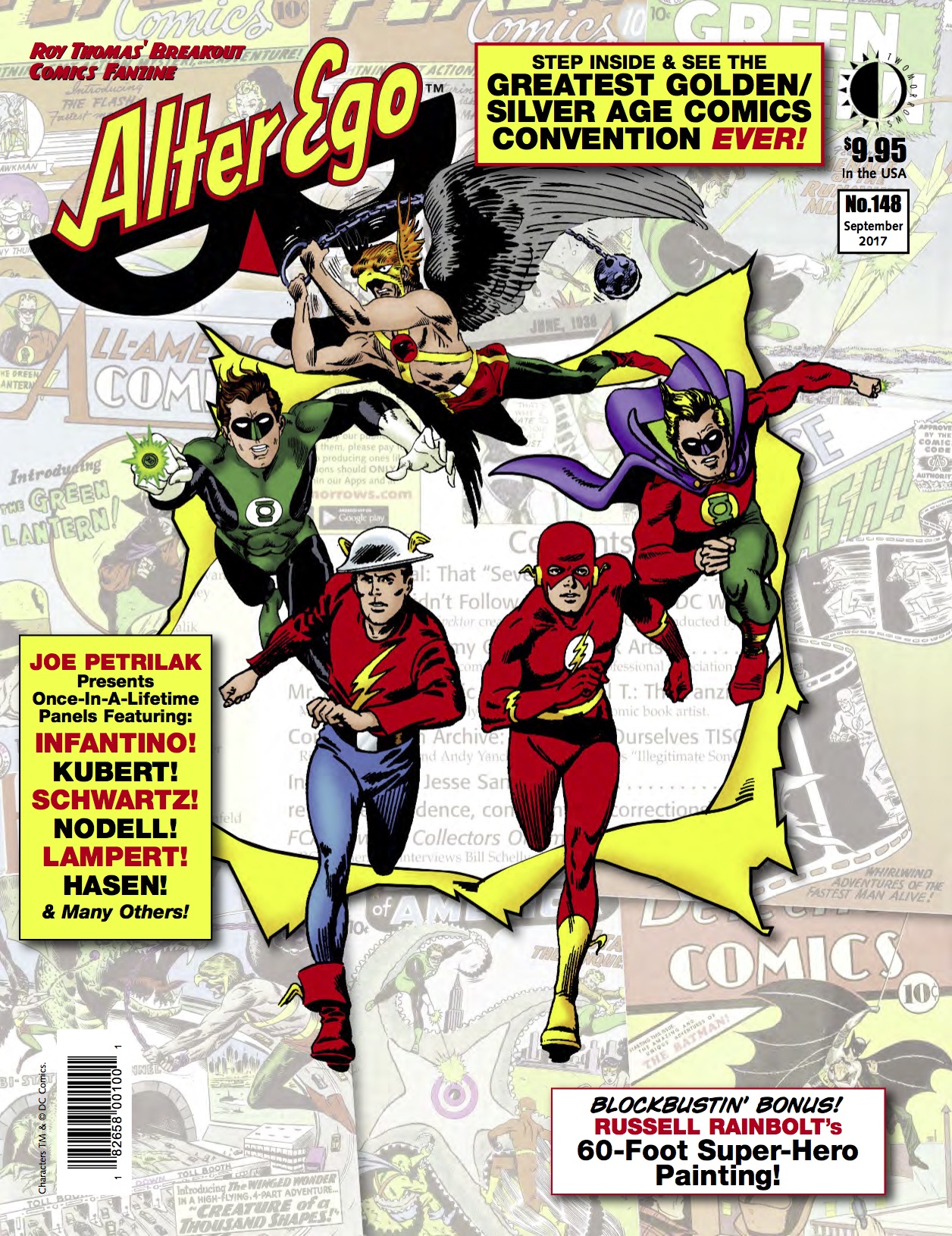

I bring this up because I just got a copy of Roy Thomas’ Alter Ego #148, which began hitting comics shops this week (though other places will get it at different times). The issue is dedicated to the All Time Classic New York Comic Book Convention, a one-off show in 2000 that gathered an extraordinary collection of Golden, Silver and Bronze Age talent, such as Julius Schwartz, Jerry Robinson, Carmine Infantino, Joe Kubert, John Buscema, Irwin Hasen, Irv Novick, Dick Ayers, Marie Severin, Jim Shooter, Joe Giella, Frank McLaughlin, Dave Cockrum, Dan DeCarlo, Mike Esposito, Joe Sinnott, Marv Wolfman, Ramona Fradon, Bernie Wrightson, Martin Nodell, Thomas himself and many others.

It took place at the Westchester County Center in White Plains, just north of New York City. About a mile from my house.

And I didn’t go.

Not only didn’t I go, I didn’t even know about it.

As I sit here typing this, my mind is completely blown just thinking it over.

Thankfully, Alter Ego #148 features detailed, you-are-there recollections, photos and, most importantly, transcripts of panels featuring the likes of Schwartz, Infantino, Kubert and Nodell. It was the 60th anniversary of the Flash and Green Lantern so those two DC stalwarts were front and center at the show. (But there were many other panels as well and Thomas notes that a second issue dedicated to the convention is planned for the future.)

Irony of ironies, about 15 years later I was part of Cliff Galbraith’s crew that put together the one-off New York Comic Fest at the same venue that featured major creators from yesterday and today, including Scott Snyder, Mark Waid, Denny O’Neil and Paul Levitz, to name a few. That show morphed into the successful East Coast Comicon. I even got a lift from my house to the show in the 1966 Batmobile, one of the biggest highlights of my Batlife.

Anyway, I still would have loved to be there in 2000. So I’ve thumbed through the issue’s transcripts and have picked out some of my favorite passages, the kinds of things I would have loved to hear with my own ears and would have loved to ask myself. This is a tiny fraction of what’s in the issue, though, so I strongly recommend you pick it up at your local comics shop or order one directly from TwoMorrows, the publisher. It’s a treasure trove of stories and insights from people who made the comics we love so dearly.

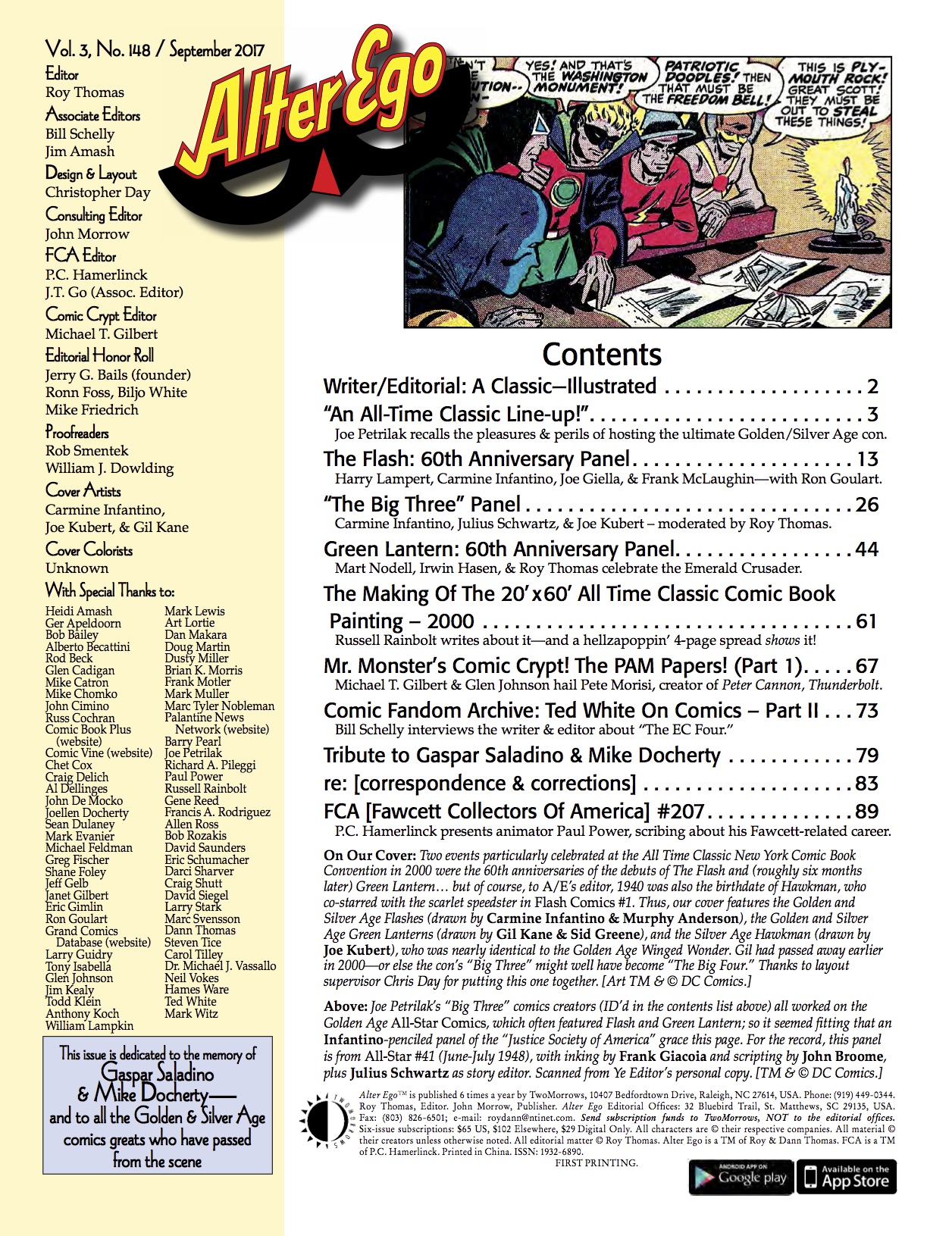

Here’s the complete Table of Contents:

In the meantime, dig these excerpts from three different panels. Most of these people have died since 2000, making these transcripts that much richer:

—

THE FLASH PANEL

Featuring Carmine Infantino, Joe Giella, Frank McLaughlin, Harry Lampert. Moderated by historian Ron Goulart.

Goulart: Let’s jump ahead in time to the second Flash. Carmine, now you created, basically—

Infantino: Well, I started off with his Flash. (Indicates Lampert.) And then, later on, the thing died. Then they brought it back. There was nothing momentous about it. I remember when we first got the thing to do [in 1956]. Julie Schwartz called me in and said, “We’re going to do super-heroes again.” I didn’t care. We’ve got work to do, was all I cared about. (Laughter.) No one was impressed with the Flash or anything about it. You never thought anything was going to happen. And then the first issue sold, and then they tried the second. Then, about the third, they knew they were onto something.

—

Goulart: Let’s bring our other two panelists in. Joe Giella first. How did you get involved with The Flash? We’re talking about the Silver Age.

Giella: I guess when Carmine started, Julie put me on the Flash. Julie could tell you that, though. I always enjoyed working with the Flash. Frank Giacoia—we both started at Timely Comics. Frank came to DC, and he wouldn’t rest until he got me out of Timely Comics.

I finally got over there and then they put me on the Flash, Batman and other characters. But then, Batman and Flash are my favorites. I always enjoyed working with them. (Crowd applause.)

Goulart: (To McLaughlin:) Would you like to get in on this?

McLaughlin: I think I came in right after Joe. What always amazed me about the Flash and the way it was drawn is how this guy here (Carmine) was able to capture motion. Nobody came closer to actual motion on a piece of paper than this guy could. It was just amazing how— (applause). Boy, and as far as storytelling, can’t beat it. So I’m very happy and honored to be able to work on the strip. It was a lot of fun.

Infantino/Giella

Infantino: I had great inkers on the thing, so I was very fortunate (applause).

Goulart: So, you guys. What part did Julie Schwartz play in—

Infantino: A major part. All I remember—and this is only the level I can give you—I was called one day by Schwartz to come in and he said, “You’re going to be doing the Flash from now on.”

I said, “We did that 20 years ago.” (Laughter.) Something new? He said, “It’ll be new. Don’t worry about it.” Julie is not the funniest guy in the world. Very serious guy. Bob Kanigher wrote the script. That I know, because Bob handed me the script.

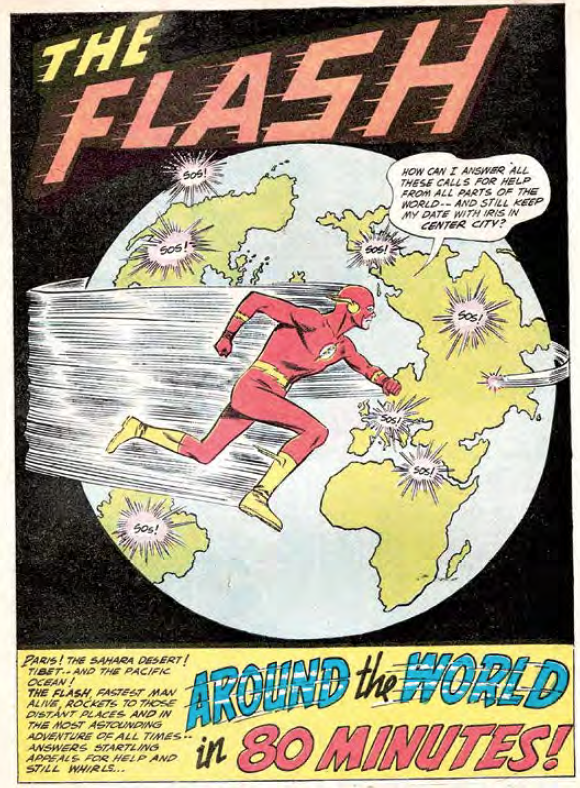

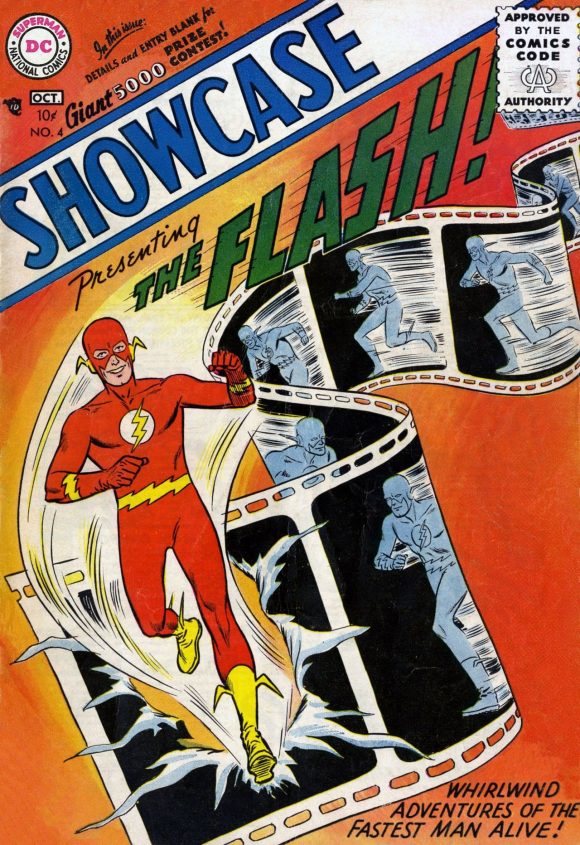

And then Bob did a very rough drawing of the cover. It’s the one with the Flash on the filmstrip. And I said to him, (NOTE: Carmine seems to be referring here to Kanigher, not to official editor Schwartz) “What do you want the costume to look like? The old one?” He said, “No. Go design something.” So, I said, “Do you want to see it?” He said, “No. Just do it and bring it in when you’re finished.” (Laughter.)

Carmine Infantino pencils, Joe Kubert inks. From a Robert Kanigher cover design.

All I remember—after the first one—I do believe, he was off the thing after the first one. Why, I don’t know. That, you’ll have to ask Julie. I don’t want to get involved in that thing. I only know that the scripts, I did them and brought them in and that was it.

The costume was fairly simple. I got a very simple drawing for the thing and I thought of the old Flash and modified him somewhat. And that’s how he came alive.

Goulart: Joe Kubert worked on that first story.

Infantino: Yeah, Joe inked the story. That’s right. I brought that in, and I didn’t even know Joe did it until somebody told me later on. Because we never saw each other that much. We worked from home. You worked and then you came back in. Although, at one period, Joe had a studio in the city somewhere. He had models and everything else up there. It was a wild place. So, I knew if I went up there, I’d never get anything done. (Laughter) I’d actually go home and work, then visit Joe. (Laughter.)

—

THE “BIG THREE” PANEL

Featuring Infantino, Julius Schwartz, Joe Kubert. Moderated by Roy Thomas.

Audience Member: It’s so very nice to see all three of you together in the same place. It was a pleasure meeting you and getting your autographs. I just wanted to ask something I hadn’t asked yet. You knew the market audience was children. When you drew and did your artwork, were you drawing for children, or were you drawing for adults?

Infantino: You should talk to the editor. He’s the one who established the whole thing.

Schwartz: You never thought of it that way. We were putting out magazines for 8- to 12-year olds, which was the period in the ’40s. From then on, the age just kept getting higher and higher. But we didn’t particularly aim. We just tried to tell a good story. It had to be written well and it had to be illustrated well, because you weren’t sure. We hardly did any surveys. We didn’t know who was reading the magazines. All we knew was, in the ’40s it was 8- to 12-year olds. That’s all we knew. Then we went on to other things. We had no marketing.

Kubert: All the time Carmine was editing, I never heard Carmine say, “Focus your work” towards any particular age group or a particular group of readers. The way I approached it, and I think Carmine approached it as well, was stuff had to be interesting to us. The stuff had to look right and tell…

Schwartz: That was the way I edited. It had to appeal to me. I never knew who the reader was, really. I was the reader… and I remembered what I liked when I was younger.

Audience Member: That was my next question: whether or not you read the stories you were publishing, and did you like them? I guess the answer to that is yes. You were genuinely interested.

Schwartz: Oh, yes. If you didn’t like the stories you were editing, you were in the wrong business. I could hardly wait to plot. Especially with (writer) Gardner Fox coming in at 10 o’clock in the morning, or thereabouts, and Carmine would have already designed the cover. We looked at the cover and said, “How did this crazy situation occur?”

My favorite cover was for The Flash, by the way. I hope Carmine remembers. He came up with a beautiful… It simply showed a stark close-up of the Flash, holding his hand up towards the reader like a traffic cop. …

And the big balloon said, “STOP! Don’t pass this magazine by! My life depends on it!” (Laughter and applause) I was with (writer) John Broome, who looked at it and worked out a story, but when that came out it was my favorite cover. …

I mean, once in a while Carmine would come up with a really crazy cover. Remember doing the Batman? Campy, campy. Batman and Robin watching television. Watching the Batman television show. We had to figure out that one.

—

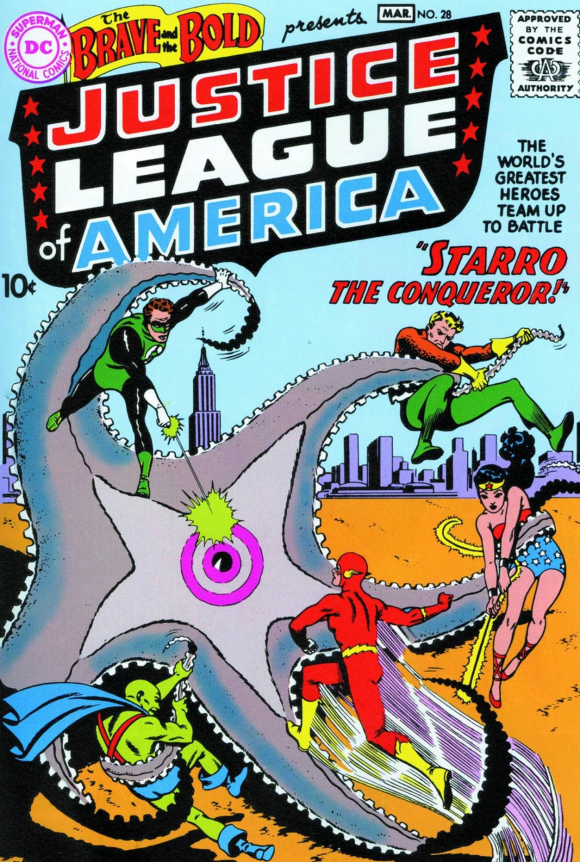

Schwartz: … The thing that I liked best was taking something that was published in the 1940s and doing it again in the late ’50s, just using the name of the character. Everything else was changed. The uniform. The background. The type of story. And all I was taking advantage of was the title. Flash. Green Lantern. …

I hated the word, the title Justice Society of America. “Society” suggests some sort of social organization. I preferred the word “League,” because everyone knew what a league was. Their baseball league, people working together in some fashion. So I came up with Justice League of America. So what I simply did was take something from a previous decade and use it again in an entirely different way. I hate to say this, but I was known as “B.O. Schwartz.” (Laughter.) Which meant “Be Original”

Schwartz. I always insisted when we did something, BE ORIGINAL.

Mike Sekowsky pencils, Murphy Anderson inks

—

Comics superfan Rich Morrissey (from audience): I’d like to ask just about all of you, because I think you all handled these, about letter pages. Because Julie had some really excellent letter pages and so did Joe when he was an editor. And so did Roy, for that matter, when he was…

Thomas: Oh, stop!

Morrissey: I look at the letter pages today and—how did you choose the letters for them and…

Schwartz: How did I choose the letters? Very simple. I read the mail as it came in, and as I read them, I’d grade them. A, B, C, D. And I had 50, maybe 75 letters, and when it came time to do the letter department, I wasn’t going to reread all those letters. So I picked out all of the A+’s. I’d put a couple of A+’s, an A-, then I’d go to the B’s and…

The important thing I did, which I learned because it enabled me to get ahead, was to put the complete address. I don’t want to go into the whole history of fandom, but the fact that I used the complete address… If you were a comic-book reader and you lived in Albany, NY, and you saw a letter from somebody else from Albany, NY, you might want to talk with them about comics. So you got in touch with them and eventually you form clubs, and that led to the birth of Jerry Bails and this guy Roy Thomas putting out a magazine like I did years earlier with Mort Weisinger.

Thomas: We didn’t even get in touch through your books (directly), because that was before you gave full addresses. You actually sent me to Gardner Fox. Gave me Gardner Fox’s home address. Can you imagine someone today: “Can you give me the home address of this writer or artist?” (Laughter.)

—

GREEN LANTERN PANEL

Featuring Mart Nodell and Irwin Hasen. Moderated by Thomas.

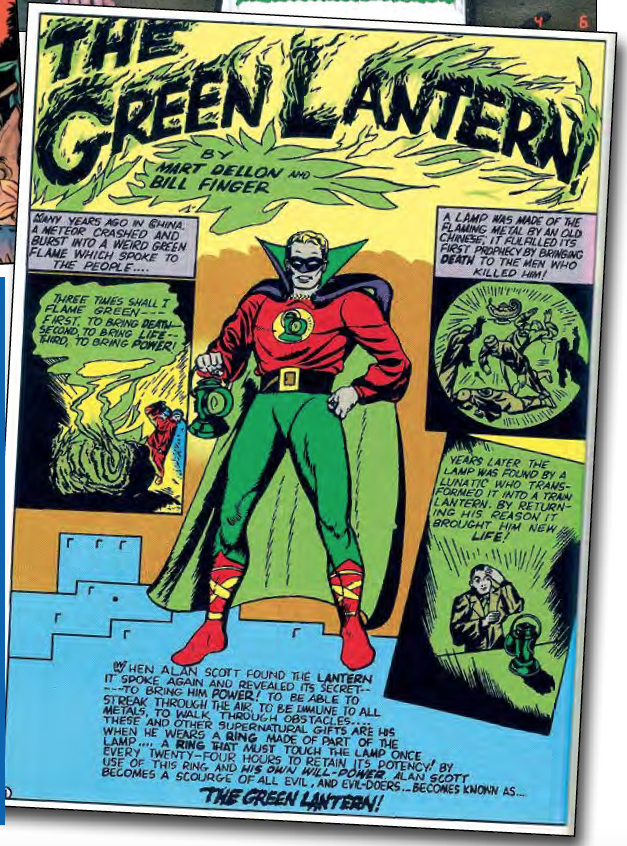

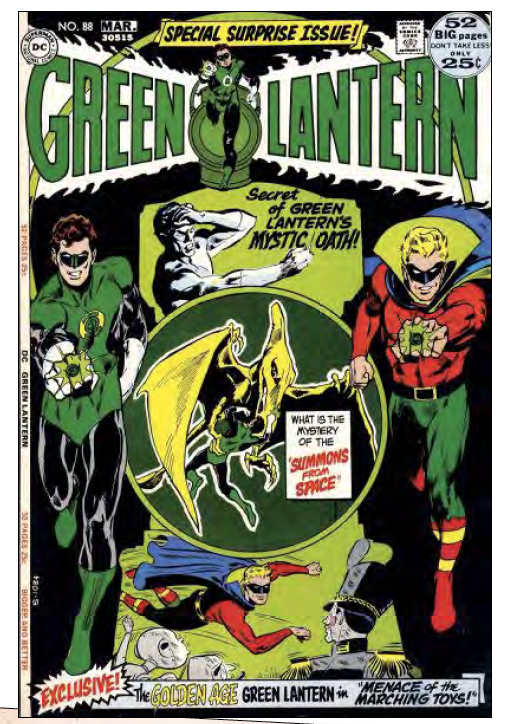

Thomas: … These are the two guys that carried the load for all those early, wonderful years of the Green Lantern, and whatever Julie said at the last panel about—I love Julie, but what he said at the last panel about only keeping the name of the Green Lantern or the Flash: not true. …

Julie and his people added a lot to the new Green Lantern and Flash, but what they kept, from both characters, was more than just the name, and, in the case of Green Lantern, more than just the color. What they kept was a concept… the concept of the man who finds a ring, however he finds it—it can be science-fiction or it can be fantasy, whatever—but who finds a ring that enables his will power and his mind to do almost anything he can think about. He has a weakness, but basically it makes him the next best thing to omnipotent, and yet still very human, because he’s not invulnerable like, say, Superman…

I wouldn’t want to take anything in the world away from Julie Schwartz, or John Broome, or my good friend, the late Gil Kane, but the fact remains, it all started back in 1940, ’41, with Mart Nodell, and [was] ably carried on by Irwin Hasen. So would you please welcome these two gentlemen…. (Applause.)

Why don’t you give us the short form of what happened? How did you create the idea of the Green Lantern?

Nodell originall used the pen name Dellon

Nodell: Well, in seeing the Green Lantern as another character, the first thing that I thought of was to have the idea of what I felt would be most important to me. If I could think of a number of ideas and put them together, it’d be best to do it with what I knew about. So first I thought of Greek mythology, Chinese folklore, Wagnerian opera, and—

Thomas: That’s the Ring Cycle of Wagner, right?…

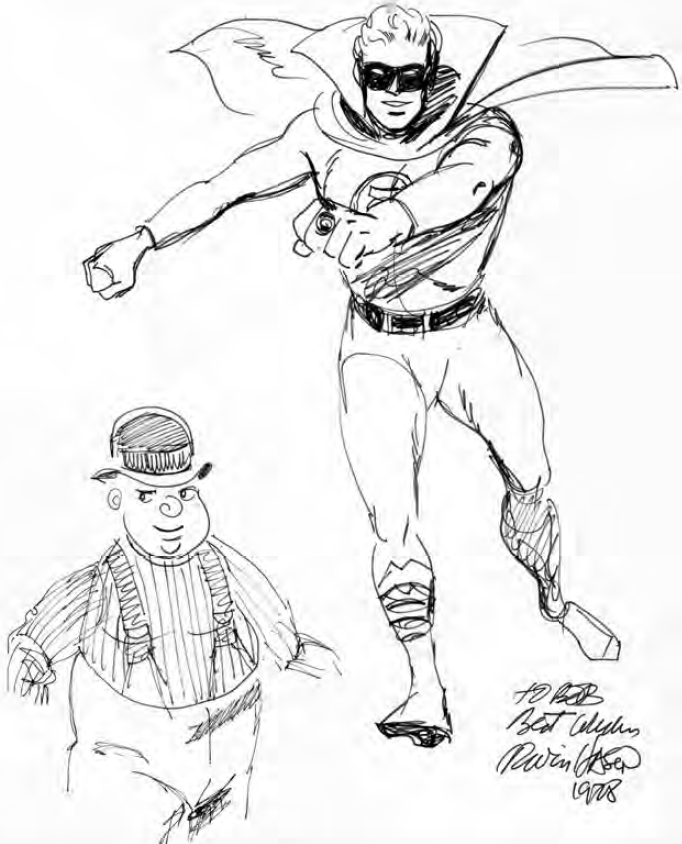

Nodell: Well, sure, you know it. Anyway, all that meant to me, first of all, was a meteor coming down in a small town in China, where there would be an explosion and there would be some metal. Secondly, the costume that I eventually worked out would be Greek-mythology-type… except that I thought of the motion picture characters who were great on swordsmanship, and I thought it’d be great to have part of the sleeve billow around. (To Irwin) You didn’t do that!

Hasen: (Mock startled) First of all, I didn’t know about that. Greek mythology and Chinese—to me it was making a living. I just did what he did, and I took— In those days you got an assignment from an editor, Sheldon Mayer; you’d come down to the office, and (writer) Bill Finger would be sitting there, and they would talk among themselves, and then he’d say to me, “Irwin, go home and do whatever you do.”

A GL/Doiby Dickles Hasen sketch from 1978

Nodell: Well, that’s what they did, but I didn’t work from that point of view at all. The only things that I did then was try to do something that— Superman had Krypton. Batman had a lot of mechanical things. So I thought the next thing would be a little bit different, so I thought “will power.” So, with will power, he could go through walls, he could fly, he could do various things. But that to me meant using the character in various ways, but I needed something additional, so I worked out the lantern… but the lantern was a green lantern.

I went down to the subway on the way home after I talked to Sheldon Mayer, and I thought of something that had to do with the fellow who was working on the tracks. And here he was waving a red lantern for the train not to come in, with a green lantern if it was OK to come in, all that kind of thing. So I decided that sounds like a workable title. So I just used the Green Lantern, and that, to me, was the character. But I didn’t want Super-MAN, Bat-MAN, so I thought maybe something else.

I also thought the lantern could be worked with the opera that you were referring to, the Ring Cycle operas—well, that was a character, a prince with unusual (abilities), where there were underground types… and he would have the ring… the ring would be his. So we used the ring as the actual way for him to fly off or to do anything else. As far as he was concerned, that was it.

Thomas: Well, the thing is that, in 1940, by this time, you’d had a year or two of what would later be called superheroes… Superman, and then Batman…. But there were already several new characters like that starting to come in, so I guess you had to have a gimmick.

Over at Timely, Bill Everett came up with an underwater hero, the Sub-Mariner. Carl Burgos came up with a guy who caught on fire. Over at Fawcett, they just copied Superman, and they had a very successful character in Captain Marvel, with all the originality that Captain Marvel also had, of course. But, unfortunately, by staying as close as they did, they got sued. Luckily, you were at the same company, so nobody was going to sue you. They wanted you to do a character. But they had to have a gimmick… and that’s why, I think, the Flash and Green Lantern, and then Wonder Woman as the female version of Superman, that’s why these characters lasted so long.

—

Audience Member: No doubt you’ve seen the Silver Age Green Lantern, Hal Jordan, who I think carried on the tradition honorably. What do you think of later versions of the character?

Nodell: Well, let’s look at it this way. The way I see it, there’s no one particular way. … Stores were different, telephones were different. There were no computers, calculators, things like that that are now in vogue… fax, and so on. Things are a lot different. So, therefore, why shouldn’t things progress? And that’s the way I’ve felt. The progression of how things may have been at that time. Different people think different ways. And different artists will think of things in a different way.

Neal Adams’ take on both characters

—

Audience Member: I was interested in the evolution of the costume—who designed the first Green Lantern costume, and how did it wind up being what it is today? The Green Lantern’s costume is so different from what it was originally.

Nodell: Entirely so. But I liked the original costume, with more color. It seemed to be a lot more fun, a lot more the different kind of character that would do different things. And there’s one thing I didn’t do. Now, even in making the character, drawing it, sketches of the character, for anyone who would look at the character, I didn’t have him take the cape and wind it around his face. I thought that would be fun, but they want to see his [facial] features, so I never did that.

—

MORE

— 100 COVERS: A JULIUS SCHWARTZ Centennial Celebration. Click here.

June 20, 2018

I wish I could have been at that event. However nothing can touch what happens in Alter Ego mag with every issue in terms of collecting historical conversations and experiences. And the issues with subscriptions come with a digital copy. Great for old eyes. Thanks Dan