The painter gets his first museum show — a posthumous salute at the Society of Illustrators that opens Wednesday, March 5.

Jeffrey Jones has been something of a mysterious figure in the world of genre art and Arnie Fenner, the director of Spectrum Fantastic Art, has written a moving tribute. Below is an abridged version that can also be found at the Society of Illustrators’ website. The full version can be found at the blog Muddy Colors.

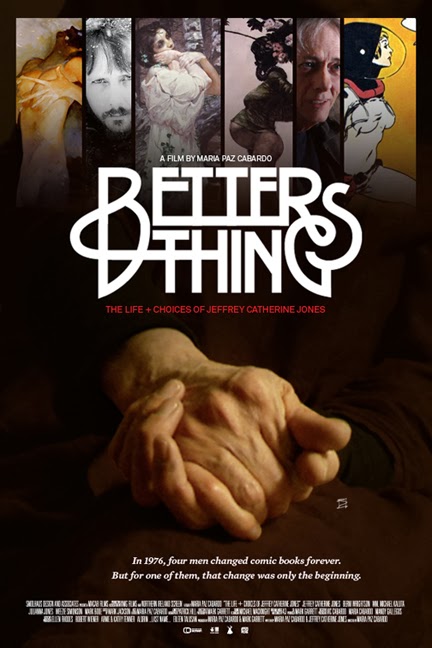

For more information, including hours, click here. The Society is located at 128 East 63rd St., New York, N.Y. Phone: 212-838-2560. On March 21, there will be a screen of a documentary on Jones: Better Things.

—

By ARNIE FENNER

I’ll be the first to admit that I did not really understand Jeffrey Jones. He was at once contradictory and perplexing and inexplicable as an artist and as a person; an odd amalgam of illustrator, cartoonist, and painter; a philosopher, a sly comedian, and a nerd. His transgender exploration only succeeded in making his story even more confusing. I always tended to think of Jeffrey as a fragile and somewhat lost soul, but—again, contradictorily—also as a person of great strength and resolve. The one certainty was that I liked Jeffrey: His art—whether created with paint, pencil, or pen—was inspiring, evocative, and memorable; as a person, he was thoughtful, humble, and kind.

Jeff started out as a science fiction fan—an amateur rocket enthusiast and avid reader of Heinlein, Bradury, Campbell, and Clarke—and honed his artistic skills drawing for fanzines like ERBdom, Amra, and Trumpet. He turned pro illustrating comic stories for Eerie, Creepy, and Flash Gordon as well as providing paintings for Red Shadows, a hardcover collection of Solomon Kane stories published by Donald M. Grant.

A move from Atlanta to New York with his wife, Mary Louise “Weezie” Alexander, led to a career creating paperback covers; he was fast, versatile, and had a style vaguely reminiscent of Frank Frazetta’s (who was much in demand, but rarely interested in increasing his workload), all of which made him extremely popular with art directors. Besides providing paintings for books by Fritz Lieber, Jack Vance, Andre Norton, and Robert E. Howard, he produced numerous romance, adventure, horror, and spy covers. Jeff also maintained a relationship with the comics industry and for a number of years provided monthly strips for National Lampoon and Heavy Metal. He produced some of his most accomplished paintings while a member of The Studio with Michael William Kaluta, Bernie Wrightson, and Barry Windsor-Smith, but the experience meant much less to him than it did to observers who desperately wished that they could have been a part of it.

In the late 1990s Jeffrey added “Catherine” to his name (though he never changed it legally), began dressing and living as a woman, and came to be described as “she” by many. Family and long-time friends, however, continued to call him “Jeff” and refer to him as “he.” I had asked Jeff how he wanted his nameplate to read on his Spectrum Grand Master Award and it says, per his instructions, “Jeffrey Jones.” “That’s how people know me,” he said. “That’s how I want to be remembered.”

The easiest thing some might say about Jeffrey is that he was born out of his time; others, of course, would agree with his occasional statement that he was born the wrong sex. He has always been portrayed as a brooding and mysterious talent, both troubled and romantic: the Byronic figure of the fantasy art world. And perhaps he was. But for my part, I’ll always remember Jeff as someone who was on a journey that was sometimes uplifting, sometimes terrifying, and sometimes heartbreaking—but he always had hope of finding a place where he felt he truly belonged. I hope finally, at long last, he has found the peace that he was looking for and so deserved.

Leave a comment!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks