Two legends from beyond the grave…

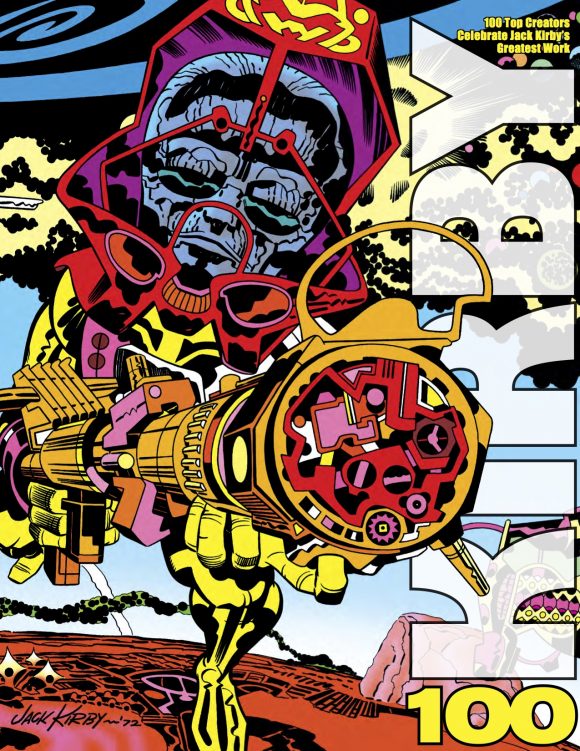

Back in August, we serialized TwoMorrows’ Kirby 100, a book in which 100 of today’s top artists — such as Walt Simonson, John Byrne, Mike Allred and Kelley Jones — paid tribute to the King on the occasion of his centennial. (Click here.)

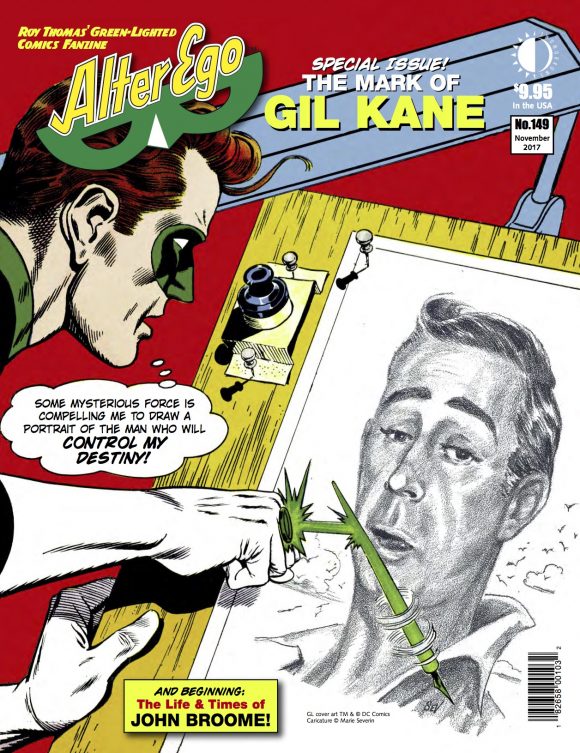

You can consider this kind of an addendum. See, Gil Kane is the subject of Alter Ego #149 — also from TwoMorrows — out 10/18. In the issue is an essay that Kane — one of my favorite artists — wrote more than 40 years ago about comics art and its practitioners. He had quite a bit to say about Kirby and in this EXCLUSIVE PREVIEW of the issue, you can read an excerpt below.

It’s fascinating to read what one legend wrote about another as contemporaries, especially when you consider that both were still deep in their careers. (Kane died in 2000; Kirby in 1994.)

Oh, and Kirby was only one part of the piece. Kane also hit on other major artists, like Hal Foster, Frank Frazetta, Winsor McCay and many others.

There’s a lot of other great stuff in rest of the issue, as well, including a pull-no-punches interview Kane gave 30 years ago.

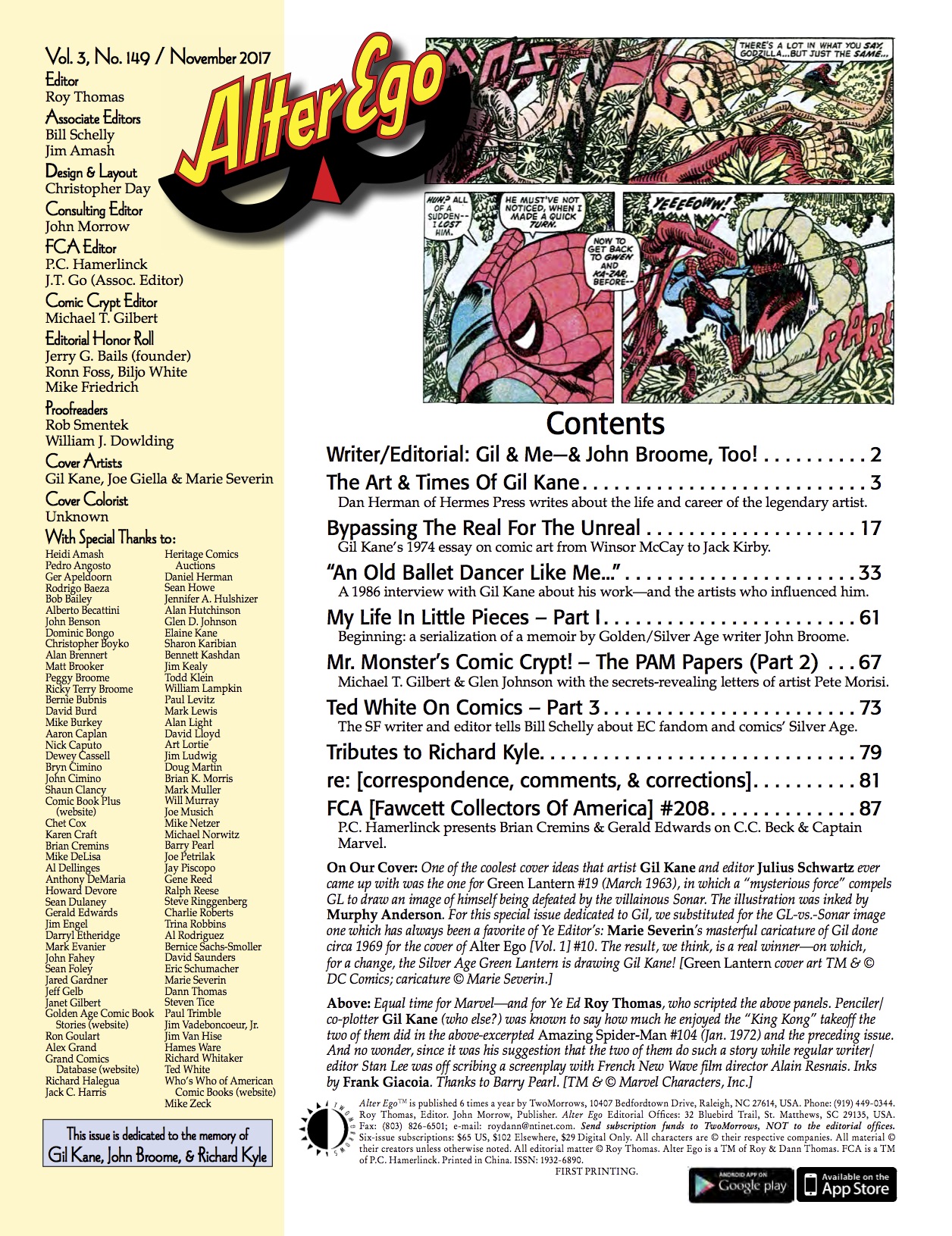

Here’s the complete table of contents:

Make sure you get your hands on the issue because this one’s packed. In the meantime, dig this excerpt:

—

By GIL KANE

One of the things that make Kirby virtually the supreme comic artist is that he is hardly ever compromised by some commonplace notion of draftsmanship. The people who make a fetish of literal form have the smallest grip on the whole idea of drama. They live and die by the external, the cosmetic effect. Thus someone in the Spanish School is elevated to a kind of deity level, while their work is anti-life. It is stillborn, while Kirby is absolutely raging with life.

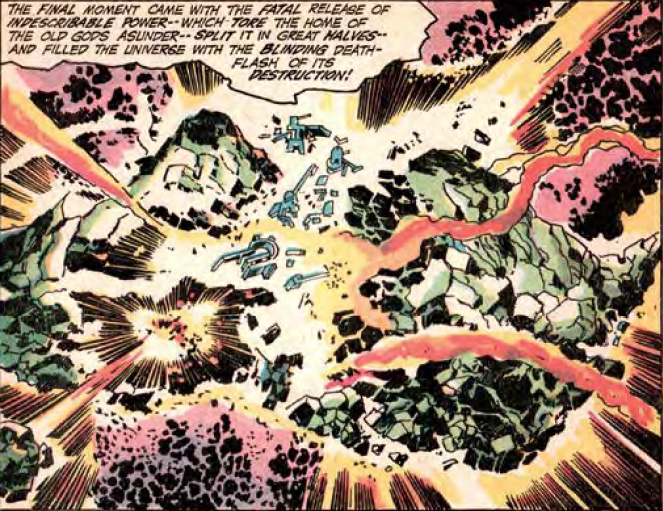

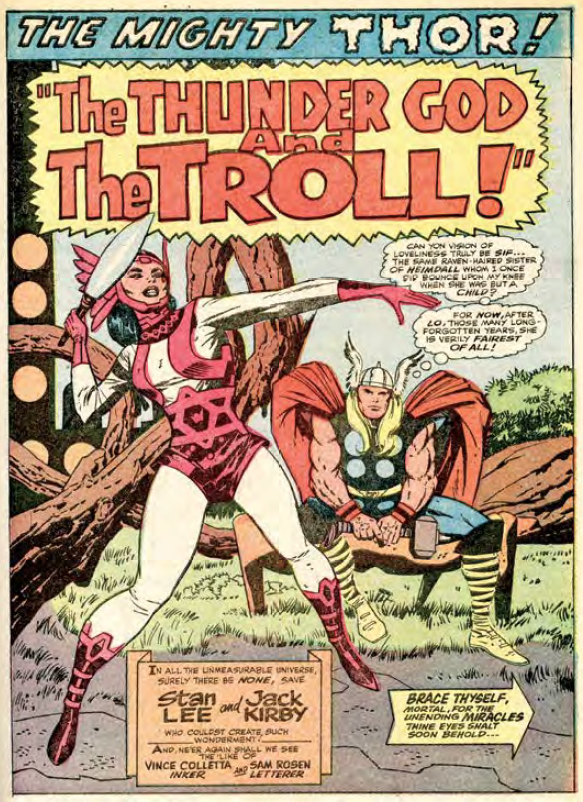

What Kirby does is to generate incredible vitality on each page. There are four or five high points in the last decade—the first year of The New Gods especially—where he had so much to give that he needed someone to channel it for him. It came out faster than it could be digested. There were four different storylines at once, all those fascinating characters he was not able to follow up on… Jack does his drawing on the basis of the very strong impressions he is continually registering; and what he draws communicates the impression better than a literal interpretation.

The New Gods

His drawings don’t depend on academic draftsmanship; they have a life of their own. He’s the one who started this whole business of distortion, the big hands and fists. And with him, they all work, they all have a dramatic quality that makes them believable, creating enormous power in his material. And his distortion is never questioned. I do more representational figures, but the same editor will accept Jack’s figures and constantly question mine.

Correct is not right; what Jack does is project his qualities, and his expressionism is better than the literal drawing of almost anyone in the business.

—

Along these lines, the one thing you can see in Jack’s work is an angry, repressed personality.

First there is the extreme explosiveness of his work—not merely explosive, but I mean there is a real nuclear situation on every page. Then there is his costuming: on every one of Kirby’s costumes there are belts and straps and restraints, leather buckles everywhere. There are times when he takes Odin and puts composition of symmetry and restrained power. His women are sort of sexually neutral. I don’t think Jack is very interested in drawing women, but give him a fist or a rock or a machine. If his women have any quality at all, it is a slightly maternal one.

—

Kirby is one of the few artists whose characters do not always have to be in a heroic posture—they can assume naturalistic attitudes. Reed Crandall and those artists “descended” from him find it almost impossible to draw a figure that is not heroically postured. (Hal) Foster, like Kirby, had naturalistic feel; (Burne) Hogarth never did.

Kirby represents the artist with the most flair for the material. He is by nature a dramatist; all of his skill supports drama, not drawing. Besides everything else, Jack has an enormous facility; he can create effects that drive a person mad. He can set up a free-standing sculpture or machine with staggering weight and impact. What kind of life can he have led to have this alien sense of phenomenology? Bottled up inside of Jack Kirby is enough natural force to light New York City. And it’s such a pity to see all that great stuff working without someone saying, “Easy, easy.” It has just never happened—they either suppressed him entirely or forced on him ideas that were never his own.

I just wish Jack were as excited now as when he first came to National. The pictures in Kamandi are far less vibrant than the New Gods material; I remember a fish-creature he did—I’ve never seen such force in my life!

Jack’s characters are so larger-than-life that ultimately they couldn’t fight the crime syndicate or even super-villains; they had to fight these cosmic figures in order to accommodate the dynamism.

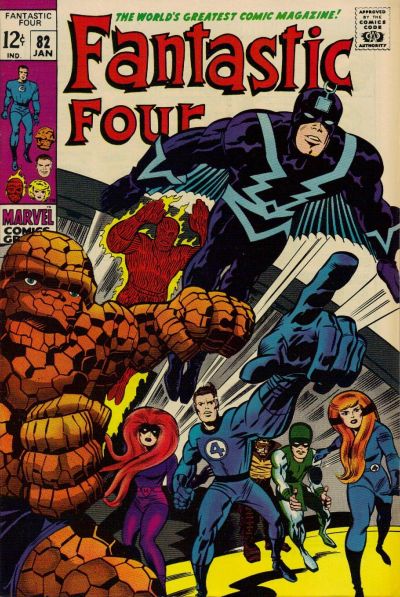

He is the only one that can handle that kind of story and make it believable. In order to do material about the cosmos, there has to be something monumental about the quality of the art. It is only externally that John Buscema resembles Jack: inside, he is much more like John Romita—attractive but not electric. His work doesn’t have the intensity, the convolution, the distortion; it doesn’t make the demands. They are constantly giving him material that he is not suited for. With The Fantastic Four John was not capable of that real freshness of perspective and insight that Jack managed to create with Galactus and a whole series of characters.

The first 100 issues are incredible, the most unparalleled sustained effort I have ever seen in comics.

—–

The complete essay first appeared in the April 1974 edition of The Harvard Journal of Pictorial Fiction.

Alter Ego #149 is out 10/18. You can get it from your comics shop or order it directly from TwoMorrows.

October 14, 2017

When Darkseid first appeared in Jack Kirby’s Fourth World stories, he was fully formed, much like Joker was in Batman #1. While Matt Wagner’s Grendel is a study in “formalized aggression”, Darkseid is a study in pitiless ambition; Darkseid does not have a merciful bone in his body. Darkseid’s quest for the Anti-Life Equation kept his ambitions in check under Kirby’s pen, subsequent creators have favored unleashing the Anti-Life Equation and lost focus on Darkseid himself. Jack Kirby understood that giving Darkseid what he wanted would mean the destruction of all sentient life; this understanding is what makes his Fourth World stories the greatest epic in mainstream comics 😀

October 15, 2017

Excellent analysis, Brad!

March 7, 2020

This is a pretty golden view on Gil Kane.