One comics legend writes about another, here at 13th Dimension.

Jim Steranko is one of comics’ greatest artists ever — enormously popular and wildly influential to this very day. We’re also proud that he will be a guest at the EAST COAST COMICON on April 11-12 at the Meadowlands. You can meet him there and get tickets here.

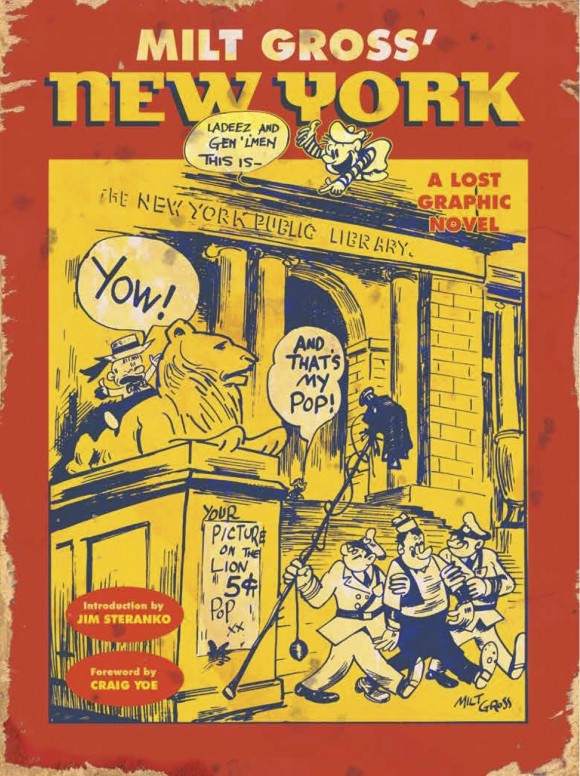

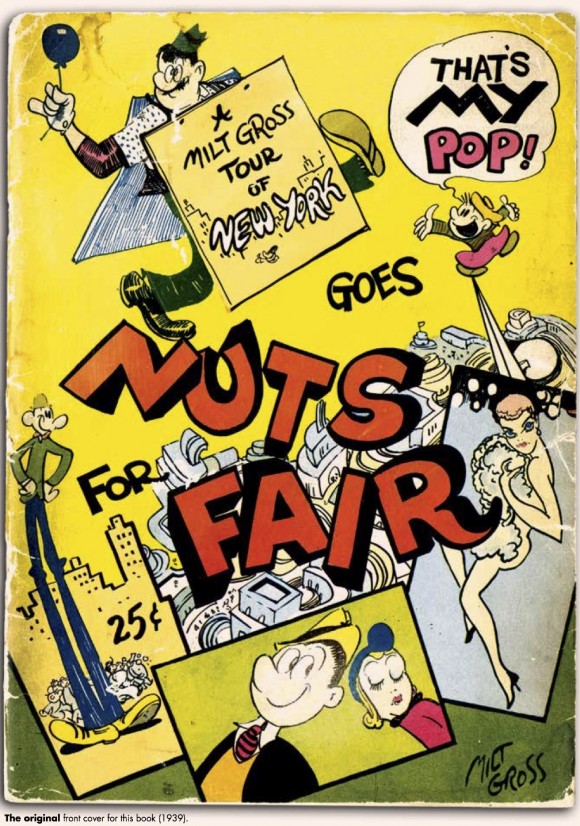

In this 13th Dimension EXCLUSIVE excerpt from the book MILT GROSS’ NEW YORK, published by IDW and Yoe Books, Steranko turns his learned eye toward one of comics’ great voices of the 20th century. The book, a lost graphic novel from 1939, is a real gem and can be ordered here as well as at many fine comic- and book-selling establishments, online and otherwise. This is a classic you DARE. NOT. MISS.

—

—

SPRIG IS COBE!

It was the line “Sprig is cobe!” that converted me.

As someone who has spent a significant slice of life at the typewriter facing the challenge of being entertaining, those three words made me a believer of its author’s brilliance. Or to put it another way, I was Grossed out! Or perhaps Grossed in!

Either way, I was hooked. Of course, I had already witnessed Milt Gross art in comicbooks, but it wasn’t until afterward when I discovered his literary skills that he pocketed my esteem. How had I missed the point? Born too late! When I discovered Gross’ comics’ work, he had already made his mark in animated films and published numerous books, then abandoned his unique Flatbush shtick to join a battalion of cartoonists in the four-color campaign of standard, straight-ahead humor, where the point men—Carl Barks, George Carlson, Jack Cole, Dick Briefer, Walt Kelly, Chad Grothkopf, Basil Wolverton, and a few others—presided with little satisfaction, compensation, or recognition.

Gross’ early strip efforts imitated those of his favorites—Bud Fisher to Rube Goldberg to Fontaine Fox—but weren’t yet true to his vision. Appropriately, the further he got away from those influences, the more his Gross instincts emerged. As a draftsman (and ersatz philosopher), he was at the opposite end of the spectrum from cartoonist Winsor McCay, for example. Gross’ panel and page composition was negligible, if it existed at all. But what he lacked in graphic virtuosity, he made up for in spades with staggering literary dexterity. His command of malaprops, fractured Yinglish, and fruitcake pronunciation is still unparalleled—the element which typifies his most memorable efforts.

His comicbook work was defined by a manic, over-the-top narrative style showcasing characters with skewed eyes, mouths under their ears, and sausage noses, all from the Catalog of Radically Grotesque Cartooning. It was the pratfall taken to its highest level—or perhaps what we’d now associate with personality disorders, such as IED (Intermittent Explosive Disorder). Distortion was so rampant, it flirted with surrealism—not to mention violence so aggrandized, it may have affronted even Chuck Jones! Was it his way of expressing the darkness that dwells in the hearts of most comedians? Possibly. But whatever it was, none did it bigger, broader, and better than Milt Gross.

His visuals were often as erratic as his characters’ demeanors, in part because his comicbook work paid less than his earlier film and magazine assignments—no layouts, no comps, a system used by many, if not most, artists of the period. Is there some crime in the concept that less pay engenders less effort? Much of Gross’ panel work suggests he never redrew an image, that the first thought in his head was what he pummeled onto the page.

Sacrilegious? We’re not talking nuclear warheads here, Shlomo! Did it work? Sometimes, but too often his pages, figures, and narratives appear to have been knocked out with assembly-line expedience. To make page rate and deadlines, he undoubtedly worked from minimal pencil layouts and finished with a scribbly pen line. The end result—never as precise as that of many peers—surprisingly added to the raw vitality and fireball velocity of the work. It is that bottom line by which Gross’ material will ultimately be assessed.

Yet for all his originality and drive, he ignited no major revolution and had few overt imitators, except perhaps Fred Schwab, Frank Owen, and Victor Pazmino. The problem with Gross’ pedal-to-the-metal approach was that he rarely embraced rising and falling dramatic structure (a pacing device used to build tension, and which holds all stories—from jokes to epics—together). Instead, Gross barreled full throttle through almost all his comicbook tales either unaware or unconcerned that when everything is lightning-paced, nothing is lightning paced—aka speed without variety is boring. Johnny One-Note! On the other hand, it is clear that Gross had tampered indiscriminately with the Laws of Dramatic Pacing. He simply had his own screwball timing—and he was unabashedly masterful at it!

Across the World Wars, the period Gross rose to prominence, Zukor, Laemmle, and Mayer dominated the Hollywood arena. Kern, Gershwin, and Berlin paved Tin Pan Alley with hits. Cantor, Jolson, Brice, and the Marx Brothers defined the national entertainment scene. Considering the manic energy Gross invested in his dialogue, it is not unreasonable to imagine him (a doppleganger for Chaplin) harboring a latent desire to be a performer on stage, rather than a paper practitioner. (At the time of his death in 1953, Gross developed and completed two episodes of a children’s TV show, of which he was host.) Perhaps that is a clue to why his execution of the phonetic resonance and beat of ethnic speech is still unequalled.

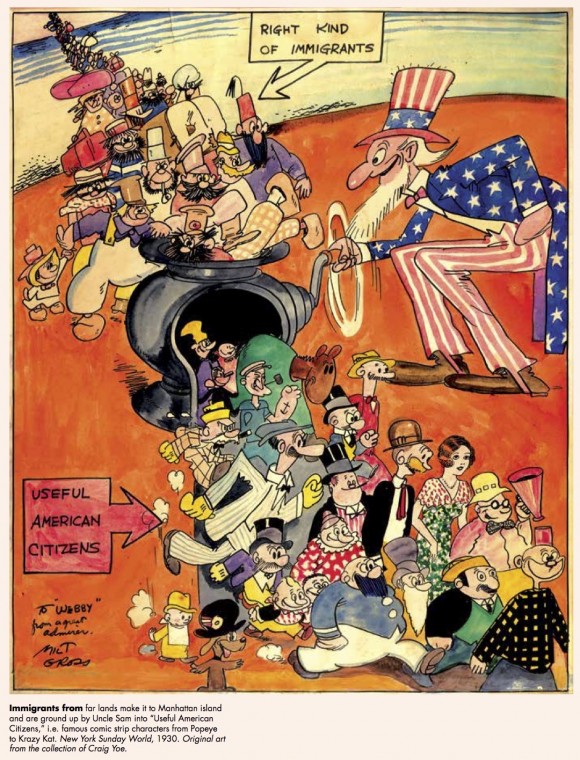

What the AMOS ‘N’ ANDY show was to blacks, Milt Gross’ oeuvre was to Jews. Both predicated their humor on ethnic backgrounds (even though the former’s creators, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, were as white as vanilla pudding), not uncommon in the vaudeville (“wodewheel” in the Gross Lexicon) era. Rampant PCness may hackle over his approach today, but there was never a mean-spirited syllable in his work. Instead, he invented his own ethnic stereotypes, and recruited them to introduce a goyish audience to the Yiddish idiom, to spread the word about Jewish geniality, warmth, and humor. And if that doesn’t cover it, he simply dropped into the classic literary tradition of writing about what he knew about!

Interestingly, he peppered little, if any, Yiddish into his work, preferring his cast to speak in English with dialect so inventively zany, it was often puzzling! Puzzling, but hysterical! Unpredictable and screwloose! In retrospect, it may have prompted one to wonder which took more time: Gross encrypting his dialogue or readers deciphering it! And maybe that was Gross’ point: to challenge and involve his audience so deeply they became his collaborators—basking in the satisfaction of decoding his insanity!

Those skills are evident in his prime 1920s volumes, NIZE BABY and DUNT ESK!!. The one in your hands might be called the Lost Gross, easily the most difficult of all to locate—until now. But I’ve said enough. It’s your turn to be Grossed out. Remember: Sprig is cobe!

—Steranko

—

JIM STERANKO is one of the most controversial figures in pop culture, with a dozen successful careers to his credit. As an illustrator, musician, art director, magician, designer, historian, escape artist, sideshow fire-eater, male model, pop-culture lecturer, and publisher, Steranko has cut a ferocious path through the entertainment arts. As artist-writer of Marvel’s S.H.I.E.L.D., CAPTAIN AMERICA, and X-MEN, he rocked the world with a revolutionary, new cinematic approach never before explored in comics’ history, including the creation of more than 150 original narrative techniques. In 1975, he authored the noir detective thriller RED TIDE, the First Modern Graphic Novel. As a filmmaker, Steranko collaborated with George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Francis Ford Coppola on some of their biggest hits. He has been cited by Michael Chabon as an inspiration for his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel THE AMAZING ADVENTURES OF KAVALIER & CLAY, by Jack Kirby as the model for Mister Miracle, and by WIZARD magazine as one of the Top Five Most Influential Comicbook Artists of All Time. He has won numerous awards in both Europe and America, lectured on popular culture, and exhibited his work at more than 300 exhibitions worldwide, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, and the Louvre in Paris.

April 5, 2015

I reserved my copy!