A NEW THREE-PART SERIES: Comics are wonderful. But are they fine art? Historian Arlen Schumer argues very much in the affirmative.

Arlen Schumer will be speaking at EAST COAST COMICON — which 13th Dimension is sponsoring — and here’s a preview of his lecture, excerpted from his verbal/visual essay slated to appear later this year in the British hardcover anthology A-1.

—

By ARLEN SCHUMER

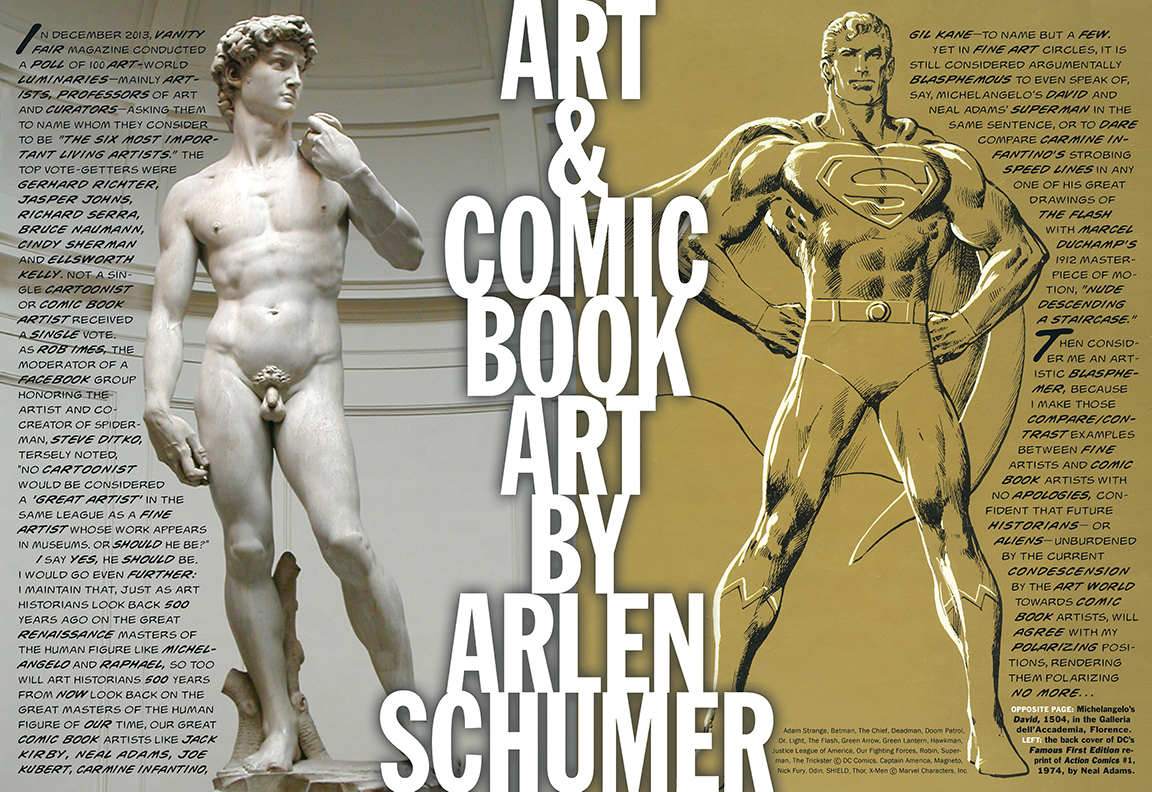

In December 2013, Vanity Fair magazine conducted a poll of 100 art-world luminaries — mainly artists, professors of art and curators—asking them to name whom they consider to be ”the six most important living artists.” The top vote-getters were Gerhard Richter, Jasper Johns, Richard Serra, Bruce Naumann, Cindy Sherman and Ellsworth Kelly. Not a single cartoonist or comic-book artist received a single vote. As Rob Imes, the moderator of a Facebook group honoring the artist and co-creator of Spider-Man, Steve Ditko, tersely noted, “No cartoonist would be considered a ‘great artist’ in the same league as a fine artist whose work appears in museums. Or should he be?”

I say yes, he should be. I would go even further: I maintain that, just as art historians look back 500 years ago on the great Renaissance masters of the human figure like Michelangelo and Raphael, so too will art historians 500 years from now look back on the great masters of the human figure of our time, our great comic book artists like Jack Kirby, Neal Adams, Joe Kubert, Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane—to name but a few.

Yet in fine art circles, it is still considered argumentally blasphemous to even speak of, say, Michelangelo’s David and Neal Adams’ Superman in the same sentence, or to dare compare Carmine Infantino’s strobing speed lines in any one of his great drawings of the Flash with Marcel Duchamp’s 1912 masterpiece of motion, Nude Descending a Staircase.

Then consider me an artistic blasphemer, because I make those compare/contrast examples between fine artists and comic book artists with no apologies, confident that future historians — or aliens — unburdened by the current condescension by the art world toward comic book artists, will agree with my polarizing positions, rendering them polarizing no more. . .

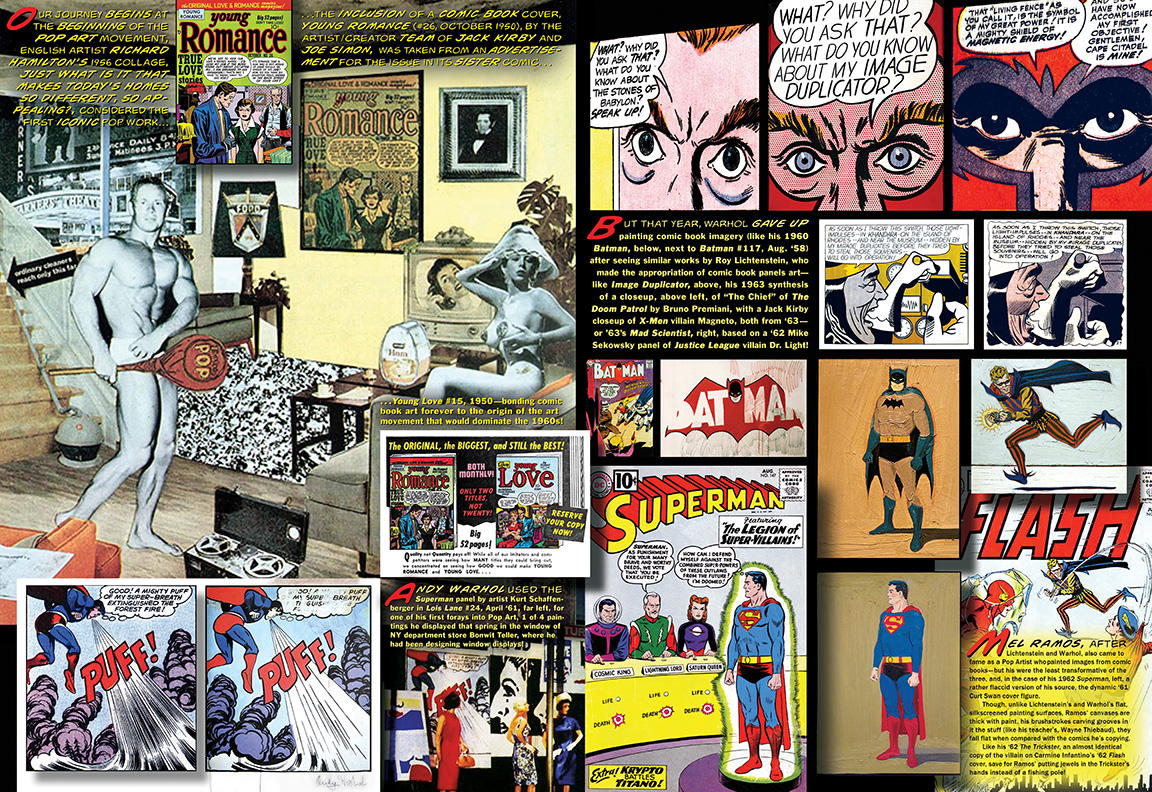

Our journey begins at the beginning of the Pop Art movement, English artist Richard Hamilton’s 1956 collage, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? Considered the first iconic Pop work, the inclusion of a comic book cover, Young Romance (#26, October 1950), by the artist/creator team of Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, was taken from an advertisement for the issue in its sister publication, Young Love #15, 1950—bonding comic book art forever to the origin of the new art that would dominate the 1960s.

Andy Warhol used a Superman panel (Lois Lane #24, April 1961) by artist Kurt Schaffenberger (1920-2002) for one of his first forays into Pop Art, his 1960 painting that he displayed in April ’61 with four others in the window of Bonwit Teller, a New York department store where he had been producing window displays.

But that year, Warhol gave up painting comic book imagery (like his 1960 Batman painting) after seeing similar works by Roy Lichtenstein, who made the appropriation of comic book panels art — like Image Duplicator, above, his 1963 synthesis of a closeup of the Chief of The Doom Patrol by Bruno Premiani (from My Greatest Adventure #84, Dec. ’63) with a Jack Kirby/Paul Reinman closeup of Magneto (from X-Men #1, Sept. ’63) — or ’63’s Mad Scientist, right, based on a Dr. Light panel (from Justice League of America #12, June ’62)!

Mel Ramos, after Lichtenstein and Warhol, came to fame as a Pop Artist who painted images from comic books — but his were the least transformative of the three, and, in the case of his 1962 Superman, a rather flaccid version of his source material, the dynamic Curt Swan (inked by Stan Kaye) Superman figure from issue #141 (Nov. ’60). Though, unlike Lichtenstein’s and Warhol’s flat, silkscreened painting surfaces, Ramos’ canvases are thick with paint, his brushstrokes carving grooves in the risen surface (like his teacher’s, Wayne Thiebaud), they nevertheless fall flat when compared with the comics he’s copying; to wit, his 1962

The Trickster is an almost identical copy of Carmine Infantino’s original Trickster (from the cover of The Flash #129, from the same year!) save for Ramos’ putting jewels in the villain’s hands instead of a fishing pole!

NEXT WEEK, PART 2 of “Art & Comic Book Art”: Infantino & Kirby vs. Duchamp & Picasso — strange but true!

—

See Arlen present Art & Comic Book Art as a VisuaLecture at the Gem City Comic Con March 28 and East Coast Comicon April 11! You can also buy his hardcover The Silver Age of Comic Book Art here.