A NEAL ADAMS CHRONICLES birthday tribute to Moore, who was born 70 years ago, on Nov. 18, 1953…

By PETER STONE

Every artist who came to Continuity Associates wanted Neal Adams to draw Watchmen. He would have made the project into a legendary event!

Neal could have pushed his way onto the project if he wanted to. In the end, though, it wasn’t his style. He looked at some of the pages and quickly praised Dave Gibbons for the amount of work, dedication and (in Neal’s mind) insanity of the pages. “The Owl guy is fat? I don’t understand,” he would say. “And look at all these panels! 9 panels a page! Every page. That’s crazy! I would never do that.”

However, Alan and Watchmen had changed how we viewed comics and what could be done with them. It wasn’t the first time, either.

In my first year of college, I could not have been a bigger comic-book fan. I read everything and anything, searching for the magic escape from real life to a dimension where heroes could be a normal kid bitten by a radioactive spider or could be a teenager who got headaches before learning he could fire blasts out of his eyes or was given a magic ring by a dying alien. I was a Marvel reader at heart, but it was Superman, Batman and the Justice League that got me into reading comics. So, I could go either way. It became a question of the quality of the work. (I loved X-Men, Teen Titans, Frank Miller’s Daredevil, Somerset Holmes by Bruce Jones, April Campbell and Brent Anderson, Jim Starlin’s Warlock, but knew nothing about comic strips or Moebius. My bad.)

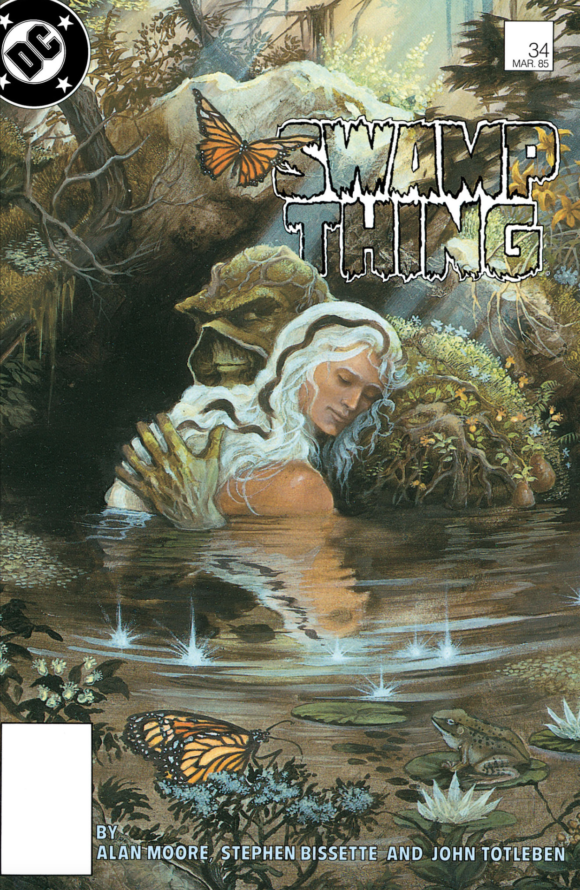

I remember walking to a friend’s dorm room, passing by an open door. Four seniors were hanging out talking animatedly about Swamp Thing by some guy named Alan Moore. I had not read it yet. Being an obnoxious freshman, I stopped to listen. They LOVED Swamp Thing and the conversation was super-intellectual. (Maybe it wasn’t, but I remember it being kind of over my 18-year-old head.) It was intense; sometimes everyone agreed, sometimes everyone was angry. I freakin’ loved it! One of them noticed me, asking me in. So, I stood in the back of the room listening. I remember making one comment, but it was based on reading Ronin by Miller so I was immediately shamed. I was told to start reading Swamp Thing right now! Right now! I left as they pulled out the weed.

The next day, the one guy who was the nicest saw me walking across a small courtyard toward my dorm room. He caught up with me, putting a comic in my hand.

“Dude! You HAVE TO read this,” he said.

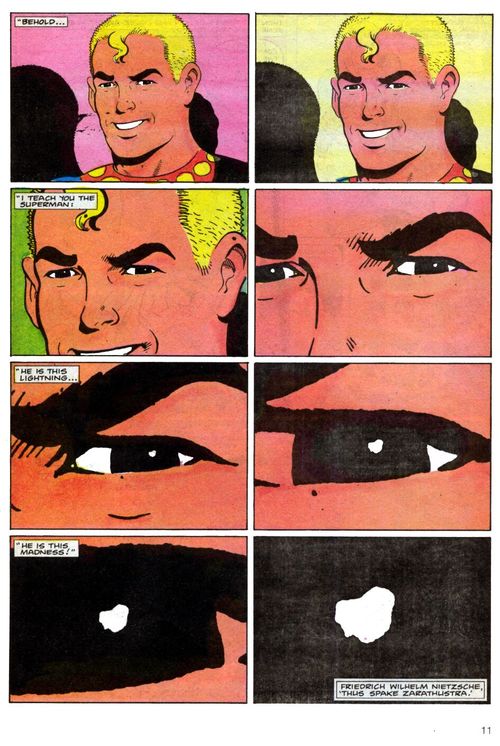

“Um. OK. Thanks,” I said. I flipped through the first few pages and the art looked like something from the 1950s. “Not really my thing,” I said as I saw the old-style art.

He looked me right in the eyes. “No. Right now.” He saw a bench nearby and dragged me to it. “Right. Now. Read this.”

I sat down, never one to disappoint anyone. I started reading. The first bunch of pages were ridiculous. Some musclebound dude fighting some science fiction bad guy from the ’50s. Then I turned the page and the words came up as the camera pulled into this foolish hero’s eyes. Captions featured Nietzsche’s “Behold! I teach you the Overman. He is that lightning, he is that madness.” Now it was getting interesting.

“A dream of snow and of fireballs. A dream of death and numbing vertigo. A DREAM OF FLYING!” Holy shit!

“There is no fear at first… only the eerie keening of the wind, the swirling, silent blizzard and the cold, sharp thrill of altitude.”

Damn, this guy could write!

I honestly don’t remember the next 10 minutes, but it literally changed my life. From the detonation of the atomic bomb on the first page and the death of Young Miracleman (who I didn’t know was really Young Marvelman) to watching poor, middle-aged Michael Moran wandering through life unable to remember his magic word… until he sees it written backward on a glass door and he becomes A GOD!

It was the closest thing I had ever encountered to a spiritual awakening/wish fulfillment/dream. (Until I met Neal Adams and Michael Golden and my personal god, Ernesto Infante.)

Years later, when people would cry in front of Neal, saying his work changed their lives or allowed them to become something greater, I understood it. I watched a handsome, African-American lawyer with a three-piece suit, Rolex and briefcase weep quietly in front of Neal because he had created John Stewart… and that he had become a better man because of those stories.

I didn’t think that kind of stuff happened – until it did.

It had happened to me. Just not in front of Alan Moore. After that moment, I bought everything I could find. (A big shout out to DC Comics and Karen Berger for finishing V for Vendetta; Eclipse Comics (Cat Yronwode and Dean Mullaney) for continuing the Miracleman epic; Moore and Alan Davis’ D.R. and Quinch for being one of the funniest things I’ve ever read; and Warrior magazine for giving Alan Moore to, well, me.)

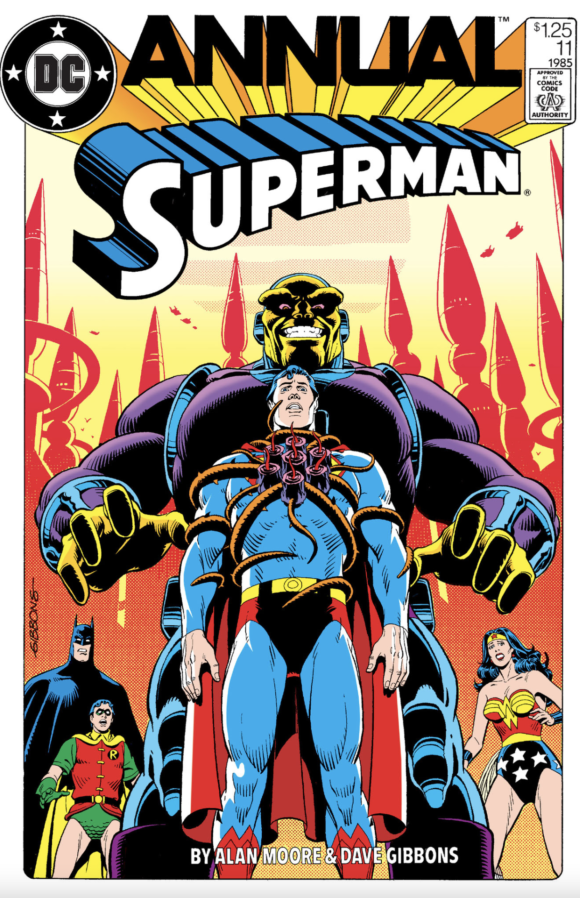

Then I got an internship (and later, a job) with one of the premiere comic artists in the history of the industry. I learned quickly to take the cotton out my ears and put it in my mouth. Who to talk about and who to NEVER bring up. Alan was one of those guys that hadn’t worked with Neal, or Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez or Russ Heath or Joe Kubert or Wally Wood. He was just one of those new guys. I personally never gave up Alan Moore because I was a devoted follower, but I didn’t talk about him much around the office. In private, I worshiped the man’s work. Every single time I thought his new project was going to let me down, he astonished me. I remember throwing his Superman Annual #11 across the room and realizing that I would never be as good as him. I remember reading his Swamp Thing “sex” issue, realizing that it wasn’t about sex at all. It was about two beings connecting in a way that I dreamed for.

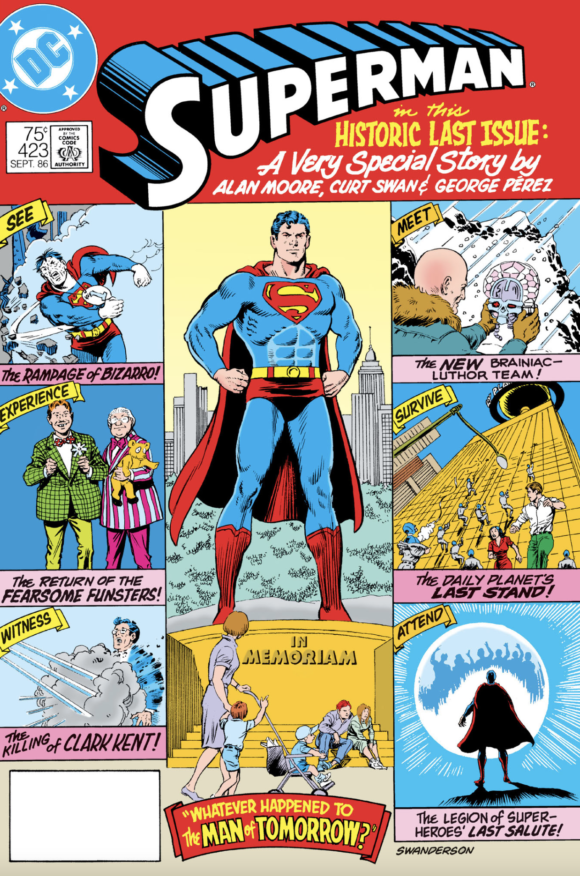

When Watchmen first hit the stands, I was working at Continuity, learning what an artist wanted from a comic story, not what a writer demanded. It was my impression that no one really knew what to expect from Watchmen. Alan Moore had finished his run on Swamp Thing, which was revolutionary to many fans, but there were many older fans who preferred Bernie Wrightson’s run and didn’t like Moore’s at all. However, combined with his short stories, Alan Moore had made a name for himself. The Green Lantern stories, the Superman Annual and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? He was rapidly building a very solid fan base.

I doubt Neal read much of his work, but those of us who were into Alan Moore were starting to understand he might be one of the most unique voices in comics in the ’80s. We all knew Frank Miller (whose Daredevil, Elektra, Wolverine, Ronin and Dark Knight Returns galvanized many of us into new ways of thinking) while some of us knew Archie Goodwin from Warren and DC. Many of us knew Chris Claremont and Marv Wolfman from the X-Men and New Teen Titans.

Once you started reading older material, Harvey Kurtzman became a true legend. How many writers could make you laugh like a fool and cry like a child with his parodies and war stories? Many of my friends and I had grown up on MASH so we were searching for that kind of story, but Harvey understood war and war stories better than the other guys who were doing them for DC. Guys like Robert Kanigher, Bob Haney, Sam Glanzman, even Bill Finger. None of them were bad writers, but Kurtzman… he was a level above.

Just like Alan Moore.

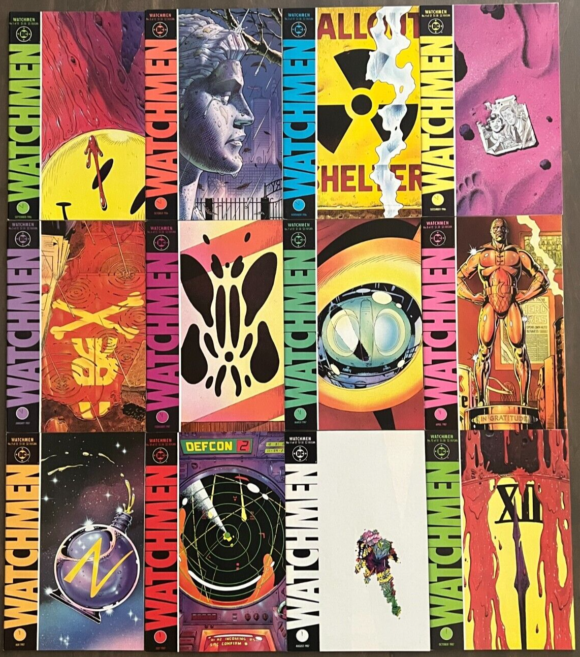

Then Watchmen hit. Moore was suddenly launched into the stratosphere of fandom. Many artists loved Dave Gibbons. Many fans loved colorist John Higgins. Neal… not a great fan, even though, years later, he learned to truly enjoy Gibbons as a hell of a nice guy and a good artist during their various cruises, conventions and dinners. He and Dave talked about art and style, allowing Neal to understand what Dave was trying to do — and how he worked his way through the dense scripts he had been given. Dave, to Neal, seemed to be an all-around great guy.

So many fans and artists asked Neal what Watchmen could have been if he drew it. He could have made those Charlton characters so much more heroic and wonderful. Neal’s response was that (generally) he was the reason that people bought his books. How could he subjugate his art style, his belief in mythic heroes, to tell a deconstructed story about heroes in a dark, realistic world. He generally disliked Watchmen. Again, it just wasn’t his thing. It wasn’t Jack Kirby’s thing either, I suspect.

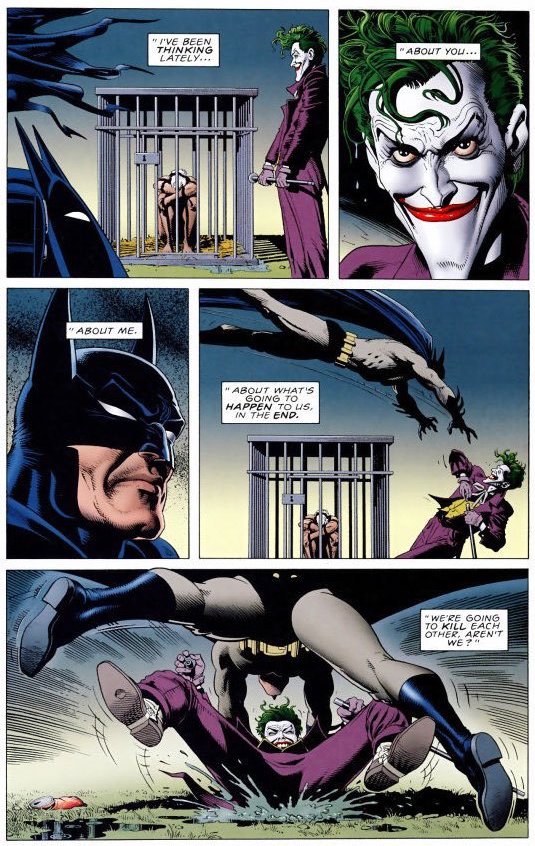

I asked him once if he liked The Killing Joke and he said no. He didn’t like it because the joke at the end wasn’t funny. At the time, I was blown away. I thought it was one of the most brilliant Batman stories ever. Now that I look back and I understand Neal better, I see what he was saying. Even Alan Moore has said he’s not a fan of his writing on that book. However, as a fan of that book, I will say that Christopher Nolan used an element of it for his Dark Knight movie. The Joker frequently asks, “Do you want to know how I got these scars?” Each time he tells a different story. Alan created that moment in my opinion. In The Killing Joke, the Joker refers to his past as multiple choice.

On an artistic note, Neal and I were both wonderfully happy to see Brian Bolland, years after the book’s 1988 publication, be able to color The Killing Joke the way he wanted to. Subtler tones, a softer, grayer palette, and an understanding of what he was trying to achieve with that book. The original printing will always exist so hardcore fans will be happy, but for those of us who recognize the brilliance of Brian’s work there will be his personal expression of how the book should have looked.

Ha! Sounds to me like someone else I know who recolored, re-inked and re-drew his classic Batman stories to the absolute horror of many older fans. And his initials are N-E-A-L A-D-A-M-S.

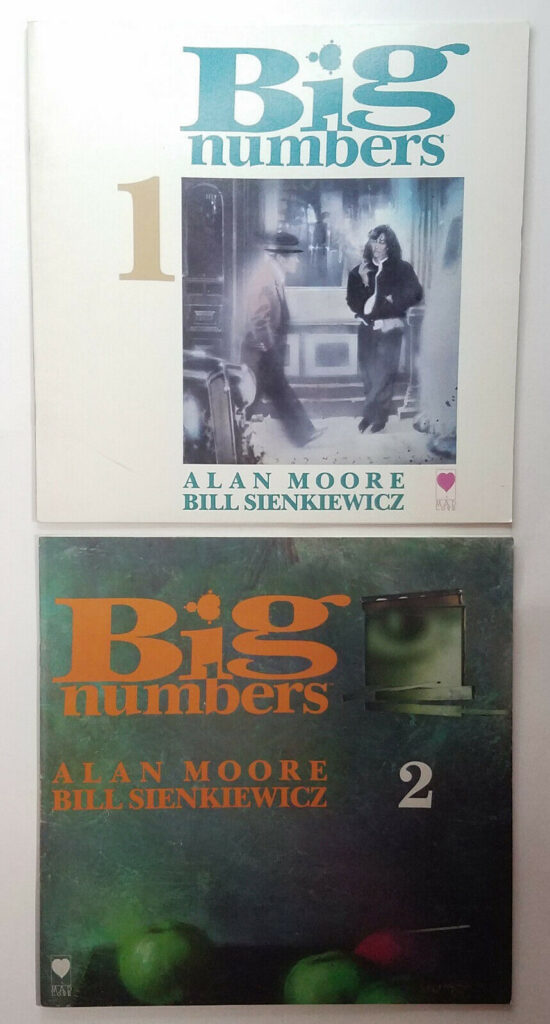

Later on, Bill Sienkiewicz painted two issues of Big Numbers, which could have been one of the greatest art jobs of his career, but I believe Mad Love ran out of money. Bill also painted Brought to Light from Eclipse Comics, a absolutely brilliant takedown of the CIA and America’s involvement in dirty wars.

Supreme, WildC.A.T.S, Voodoo, Glory, Youngblood, Lost Girls, Neonomicon, Tom Strong and so many more. Each one is brilliant in its own right. In my opinion, however, I believe one of his greatest stories was From Hell, a theoretical exploration of the “real” Jack the Ripper. Intense research into the crimes as well as the history and architecture of London itself makes this a story that eclipses almost anything he’s ever done. It also taught him about connecting the place where someone lives with the events happening there. (I’m guessing there, but I suspect he probably knew that already since he rarely leaves his hometown.)

Is there a writer in comics who has more movies and TV and video games made from his work? Swamp Thing. Watchmen. League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. From Hell. Constantine. Watchmen again (for HBO). And all the stuff people want to do, like more Constantine and Swamp Thing.

He certainly gives Neal and Frank a run for their money.

Is Moore a magician? Sure. Has he given up comics? Yep. Has he shaved in 20 years? Probably not. There is something Neal said to me early in my relationship with him that remains true today and always will be: “Separate the man from his art.”

So, Alan Moore looks weird and has mystic rings on his fingers. He doesn’t go to conventions. Barely signs anything. Writes very dense novels with no superheroes. Well… so what? His work has changed this industry. Some would say for the worse. People said the same thing about that young kid who took over The Spectre from the brilliant Murphy Anderson. His panels were angled and he drew in a far more realistic style. He certainly wasn’t the status quo. No, that kid shot the industry so far forward that we still haven’t recovered. That kid was Neal Adams.

Did Neal and Alan see the world the same way? Not a chance. But then again…

Who does?

—

MORE From THE NEAL ADAMS CHRONICLES

— TONY DeZUNIGA and the Deep Influence of Non-American Artists on American Comics. Click here.

— BERNIE WRIGHTSON: A Birthday Salute — From FRANKENSTEIN to SWAMP THING, and MORE. Click here.

—

Peter Stone is a writer and son-in-law of the late Neal Adams. Be sure to check out the family’s twice-weekly online Facebook auctions, as well as the NealAdamsStore.com, and their Burbank, California, comics shop Crusty Bunkers Comics and Toys.