From newly minted 13th Dimension contributor Hannah Means-Shannon:

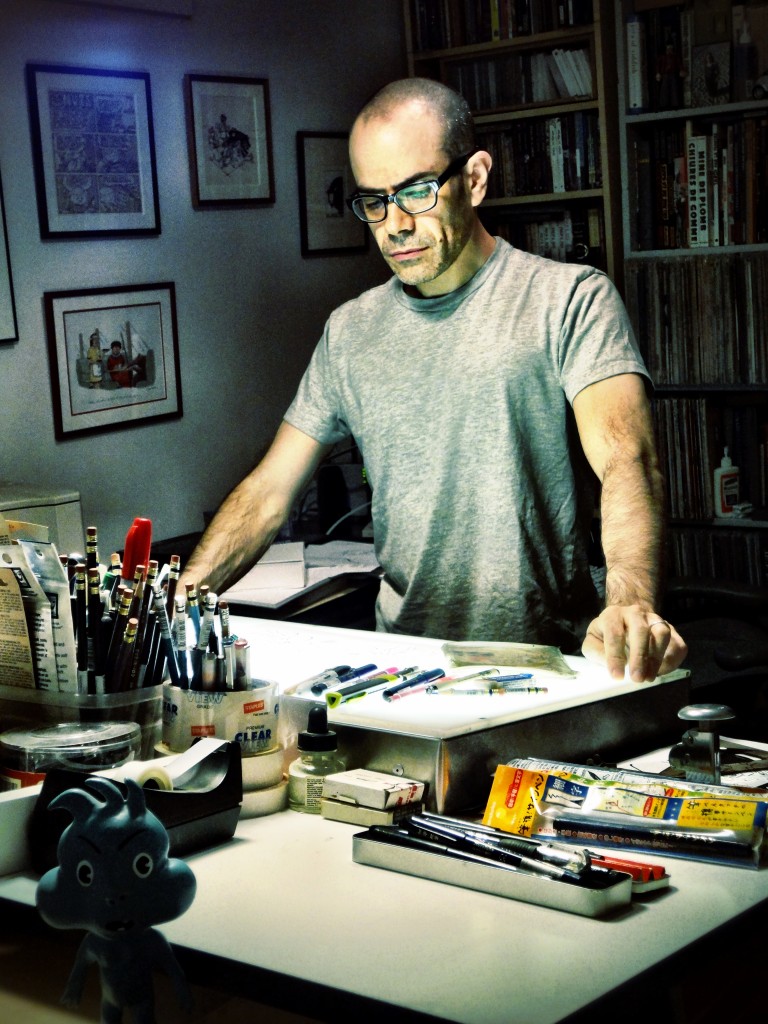

As cartoonist, satirist, and writer of both apocalyptic tales and expectation-defying horror stories, Bob Fingerman has a publication list long and diverse enough to represent an entire creative team, but his mobility is one of his defining features, and he continues to turn unexpected corners in his career.

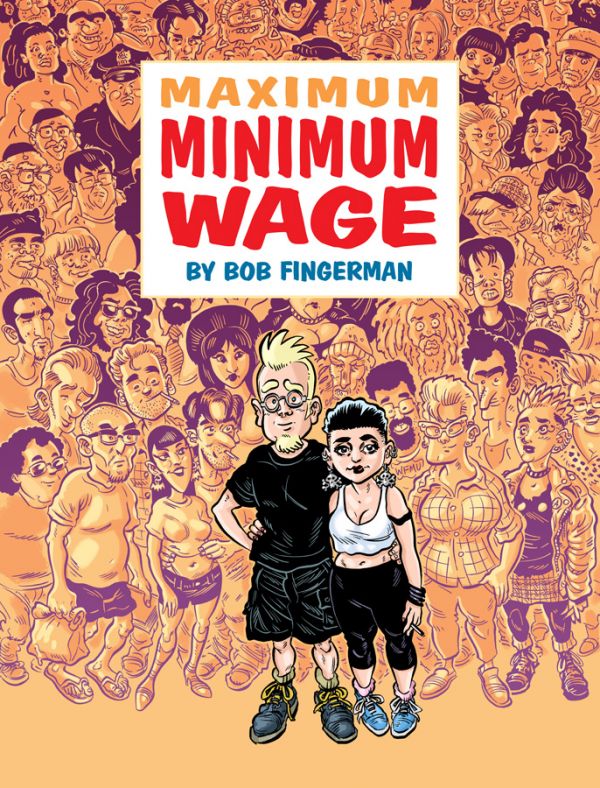

One of his earliest and most surprising changeovers came in the mid ‘90s when he moved from making mainstream comic books to producing a streamlined, challenging, and irrepressibly funny semi-autobiographical series of comics known as Minimum Wage. His jumping-off point made an indelible mark on comics in content and style, influencing the way professionals and fans thought about the medium and creating ripple effects still seen today.

When he announced that 2013 would see the release of a deluxe edition of the series from Image under the auspices of Fingerman’s mega-fan Robert Kirkman of The Walking Dead, there was definite shock, awe, and buzz. The newly remastered collection, “Maximum Minimum Wage,” has been one of the most anticipated releases of the season.

When it appeared, it elicited quite a crowd for Fingerman’s signing at Forbidden Planet off Union Square. It was one of those rare moments in comics when landmark work is acknowledged openly and receives the prestige format it’s been crying out for.

Fingerman’s roots in New York run deep. A student of the New York School of Visual Arts, Fingerman grew up in Queens and began working for the legendary Harvey Kurtzman in the mid ‘80s while still at school.

His early work consisted of parodies and satire, and he quickly branched out into work as an illustrator for Cracked Magazine, Screw, Heavy Metal, National Lampoon, and others. In the ‘90s he started working for Vertigo and Dark Horse, and spent a great deal of labor on a stylistically innovative social satire in graphic novel format, “White Like She.”

Though he was proud of the book, he had produced something so “technical and precise” that he felt the book no longer looked like his own work. The lengthy production process left him feeling “worn out” and in doubt about his future in comics.

For Minimum Wage, it all started with loose drawings in a sketchbook as he tried to decide where he was headed as an artist. Considering his own life experiences made him wonder if authentic stories might be better to tell than “generic” ones. He took a chance on blending biography with a sprinkling of fictional touch-ups to produce something that felt more immediate to his personality.

“I wanted to do a comic that finally felt like it could have only come from me”, Fingerman said about this turning point.

It may seem obvious to readers now that this was the golden key to producing a classic comic, a work so idiosyncratic that no one else could have done it before, but at the time of its release, Minimum Wage raised eyebrows as well as expectations. It struck a chord for up and coming creators who felt the same restlessness and limitation when it came to comics, encouraging them to be less proscriptive and forge their own path.

When Fingerman had finished the phase of the story he was happy with in Minimum Wage, he moved into prose, producing his first novel “Bottomfeeder,” a vampire story where he felt he could “play with language”, and his second, “Pariah,” an apocalyptic zombie tale.

Both works drew Fingerman’s attention to a new quest to find a way to incorporate humor into horror, something he feels is underrepresented in comics and prose, but is a little more accepted in experimental film.

Joss Whedon’s film “Cabin in the Woods,” for instance, was one of his favorite movies of 2012 because it traces the intersections between comedy and traditional horror motifs, and some of his favorite prose works are decidedly “over the top,” pushing the boundary between “sick” and “funny” from authors like Terry Southern, Bruce J. Friedman, and Chuck Palahniuk.

Though he’s never been one to work on novels and comic projects simultaneously, preferring to switch formats between major works, comics were never far from his mind while working on his prose.

The works of Robert Crumb, Dan Clowes, Ben Katchor, and the great European artist Moebius stayed with him. Often, his artistic influences dovetailed in theme with his prose explorations, like Richard Corben’s apocalyptic and fantastic work “Mutant World.” This cross-fertilization eventually led Fingerman to take up a semi-autobiographical mode in his illustrated novel about apocalyptic survival in “0From the Ashes.”

Working on the new edition of “Maximum Minimum Wage” has turned his attention back to comics as he ponders what’s next for his varied career.

“I’m not sure I’m done with the end of the world yet,” he said, since apocalypses keep cropping up in his works, but New York is a particular inspiration in returning to visual storytelling. It’s a stimulating place for Fingerman, where he still feels a thrill when he finds a street he hasn’t explored yet, and where both the gorgeous and hideous aspects of the city continue to inspire.

2013 has been a bumper year for Fingerman, bringing not only an outpouring of fan support for “Maximum Minimum Wage,” but also a summer exhibit of originals from the work at the Society of Illustrators. The opening featured an evening of discussion between Fingerman and friend Frank Conniff of “Mystery Science Theatre 3000” fame.

You can find out more about Fingerman at www.bobfingerman.com, and about Maximum Minimum Wage at http://maximum-minimum-wage.blogspot.com.