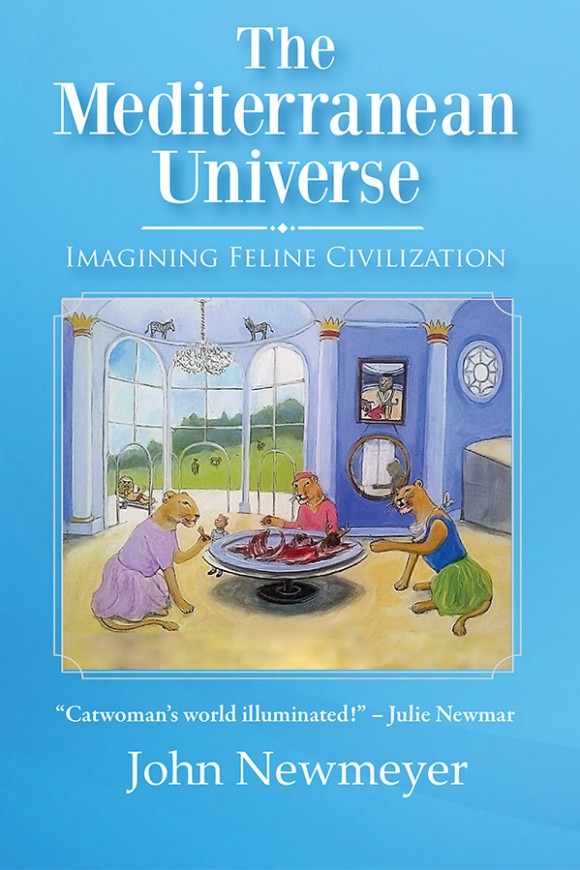

The great Miss Julie Newmar pens an homage to her brother John Newmeyer in this introduction to his new book The Mediterranean Universe: Imagining Feline Civilization. PLUS: An excerpt from one of Newmeyer‘s own essays!

The book, which is a lyrical rumination on cats (and dogs) and their meaning, is available at Amazon. We’re proud to publish Miss Newmar‘s introduction to the delightful volume, as well as give you a taste of John Newmeyer‘s own writing from a portion of Julie‘s favorite essay in the book. — Dan

By JULIE NEWMAR

“I’m gay,” my brother said to me.

“Oh!…. Okay!”

Honestly, I don’t remember that I even had a reaction to this news.

John was someone I always looked up to, even though he was eight and a half years younger than I.

We grew up in Los Feliz, a Los Angeles burb, the birthplace of Mickey Mouse and the location of the early Hollywood studios of Monogram Pictures and D. W. Griffith. The art of fencing was taught in the local dance rehearsal studios that fed the film business in those days.

The Red Line street car traversed Hollywood Boulevard long before today’s corporations memorialized themselves there. A great place to go for hot fudge sundaes with “hand-chopped” toasted almonds was C. C. Browns, next to Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

My two brothers and I walked to school and father taught engineering at Los Angeles City College on Vermont Avenue. He was head athletic and football coach there for twenty-five years and even had Esther Williams in one of his swim classes.

According to my mother, who’d had a brief career as an illustrious Ziegfeld girl, my brother taught himself to read at age three, was doing math at four, and astronomy by five. Alas by age seven he was showing signs of over-education, so mother took us both out of school (I was 16) to be shepherded on a grand tour of Europe. Her method of acculturation was by way of museums, cathedrals and catacombs. We traversed the whole continent and North Africa for a year in a jaunty little Hillman Minx motor car.

John kept logs – his room number, how many miles from the Toulouse to Gaillac. He got around on the Paris Metro by himself. He was our currency exchange point man. For him, life soon became the thrill of numbers. By high school, he was an honorary actuary. When I can’t find the answer to a problem, I call up my brother. He is the smartest person I know.

College at Caltech in the class of 1962, he remembers, had an especial esprit de corps. It was indeed the golden age of science and math during the Sputnik crisis. While many of his fellow scientists went on to help arm America’s master-of-the-universe complex, he needed a higher goal. By the time John was at Harvard, he’d gone from Physics to Psychology – getting his Ph.D by tutoring his way through college. From quarks to civil rights and later epidemiology, he had more to learn about the world.

The two of us existed halfway around different worlds the year of 1964. I was television’s Rhoda the Robot in My Living Doll (reflecting man’s passion for the perfectly controllable woman). It was the reign of baby talking blondes starting to have a brain. Rhoda had an IQ of 180. Television shows were literate then. John, in leisured contrast, sojourned his way across Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and worked on kibbutz in Israel.

Life had changed after Harvard; he moved to San Francisco and bought a Victorian mansion much against our father’s better judgment. “What do you want with that old thing?” It soon became a cooperative, governed and shared by gay men. Some of the most stimulating conversations could be heard on those Friday nights nearest the full moon for his Lunar Society dinner parties. There have been 356 dinners for which he shops, cooks and officiates in his own version of a new age salon. In ways, he is the 21st century Thomas Jefferson. A trendsetter of healthy rationality. His mentality is keenly attuned in contrast to his physical tempo, which seems almost lax. It is quite fascinating to sit in his Pacific Heights kitchen with the eleven-foot ceilings and be part of a resplendent cross-hatching of modern ideas.

Four years later, again opposing paternal advice, he purchased a thousand acres in California’s Napa Valley by engaging partners who have shared interests which match his intellectual curiosity. In time there was a vineyard producing fine Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs, under the name Olivia Brion. Now his wines are in the choice restaurants.

Portending the future, John has created a family. There is his daughter Elizabeth, a younger Julie Newmar? In looks perhaps. She is a biology major at Caltech. And Jack, fifteen, whose mother like our mother is from Minnesota, Garrison Keillor country.

“How did you do that?” I once asked. It was unstructured, I learned. “I put the word out. I put an ad in the Bay Area Reporter,” he said. “I interviewed four possible candidates and settled on the fourth.” The same was true of her choices; she chose the fourth, him.

“I wanted someone hard-headed,” he said, “feet on the ground, no divorce in the family and … not Hollywood.” The part I remember best was about the turkey baster, but he can tell you about that.

From John Newmeyer’s Facebook page: “I’ve built a “Cocktail Cruiser” for outings on the Long Lake at Green Valley Ranch. The craft runs quietly and smoothly, facilitating conversation and unspilled cocktails as the Napa landscape passes gently by.”

The tumultuous year of 1968 came along and as we were rafting down the Green River in Utah, he inspired me to campaign for Eugene McCarthy, something he had already done earlier that year. Politics became imminent in our lives; we had to change the world. I vividly remember the two of us jumping up and down on my bed to the dismay of our parents at my Harper Avenue duplex while watching a broadcast of a defeated Lyndon Johnson “retire himself” from the presidency.

John, by now an expert on substance abuse and the statistics of diseases, became the epidemiologist for San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic and the NIH, National Institutes for Health. He was also one of the first in the mid-nineties to expose the destructive effects of sugar and other “drugs that pretend not to be but really are” in his third book, The Mother of All Gateway Drugs. He has debunked the foolishness and waste that makes reactionaries feel good, but in actuality do little real good in their War on Drugs.

A favorite article “Policy Negation” is not only witty but well-informed wisdom for the ages. It is as if Jonathan Swift were writing for The New Yorker.

In his second book Road Grace, he writes eloquently about the gay universe in his essay “Alphabet of Gaydom.” His inamorato is forty-three years younger than he. John probably does know a thing or two.

His fourth book, now my favorite and most fun to read, is about – cats and dogs. I assure you I had no input!

Julie being escorted to the Castro Theatre in SF, where she received a Lifetime Achievement Award last year.

Two distinct qualities about my brother that perhaps should be known.

He never swears. He is downright easygoing. He is never in a rush and always has time for the other person. He is unperturbed by what rattles the rest of this world. It is easily noticeable how calm and inviolate it is to be in the space around him.

At other times, consternation arises, on the occasion when his cell phone rings, then all ears pick up. Immediate curiosity is aroused. What is heard is the raspy sound of an inquisitive but imperious cat from somewhere inside his clothing. Meeeouw… meeeeouw… meee…

—

And, now an excerpt from one of John Newmeyer‘s essays, in which he imagines a new breed of dog that seems familiarly feline …

NOTICE TO DOG LOVERS OF SAN FRANCISCO

AS YOU ARE NO DOUBT AWARE, THERE ARE MANY PROBLEMS IN OWNING A DOG IN A BOG CITY. IN RESPONSE TO THESE PROBLEMS, A NEW CLASS OF CANINE, THE SELF-WALKING DOG, HAS BEEN DEVELOPED. FOUR BREEDS OF THESE SELF-WALKING CLASS ARE OFFERED TO THE DOG-LOVING PUBLIC:

The self-walking dog has been specially bred for the following qualities:

CLEANLINESS. The conventional dog must be walked twice daily, and even then it is hard to find a suitable place for his excretions in the urban landscape. The Self-Walking Dog, however, is indeed self-walking: you simply let him out, and he will actually conceal his excretions underground. This miracle of behavoral engineering means that your neighbors will no longer mutter angrily about your dog’s fouling the streets. If all dog owners switched to one of the self-walking breeds, imagine how our city’s streets would be transformed!

QUIETNESS. The bark of the Self-Walking Dog is a melodious and agreeable sound, in the tenor to soprano range. Never again will your neighbors call you in the middle of the night* to complain about your dog’s howling.

*Except during mating season.

…

INDEPENDENCE. Your Self-Walking Dog will not embarrass you by fawning or obseqious behavior. Should you leave him alone in your apartment for a day or so, he will not howl in loneliness, but will amuse gimself by furniture acrobatics, window sitting, or fabric disassembling.

—

Sounds purr-fect! Again, you can order The Mediterranean Universe: Imagining Feline Civilization here. — Dan

Trackbacks/Pingbacks