Because YOU demanded it!

—

Gotta love alternate realities, right? Stories that take the familiar, then spin them, oh, 45, 90 or 180 degrees.

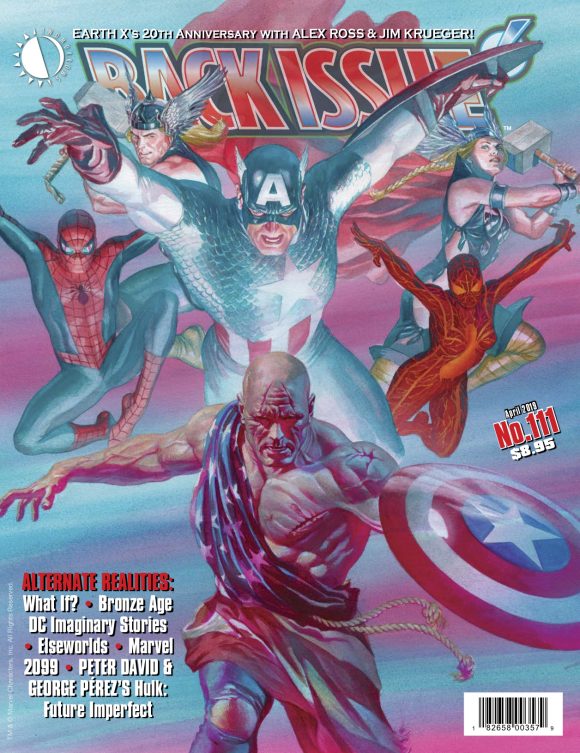

Well, Michael Eury’s Back Issue #111 — out March 13 — explores those roads less traveled, with histories of Marvel’s What If? and Earth-X, DC’s Elseworlds and “imaginary stories” — and more.

Just check out the table of contents:

So much fun.

Anyway, for our usual EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT, we’re gonna dive into John Wells’ look back at DC’s imaginary stories.

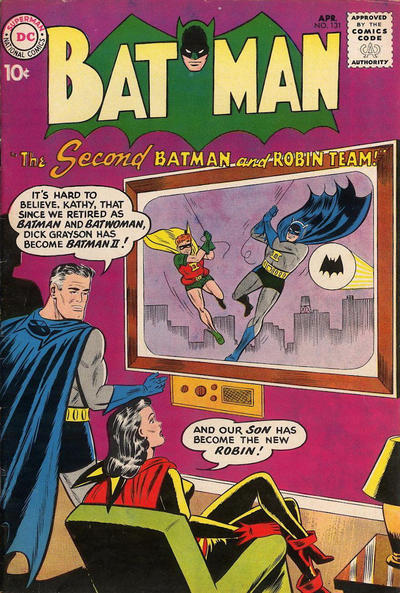

As a kid, I was a big fan of the “Batman and Robin II” tales that posited a world where Bruce Wayne and Kathy Kane wed and had an improbably red-headed son who became the next Boy Wonder to an adult Dick Grayson’s Caped Crusader. (The set-up laid the groundwork for Grant Morrison’s Dick Grayson/Damian Wayne spin decades later.) Those stories were reprinted in the ’70s and offered a tantalizing glimpse of what might be.

Wells gets into that, and more. So enjoy this piece — and make sure you check out the rest of it in the issue itself.

—

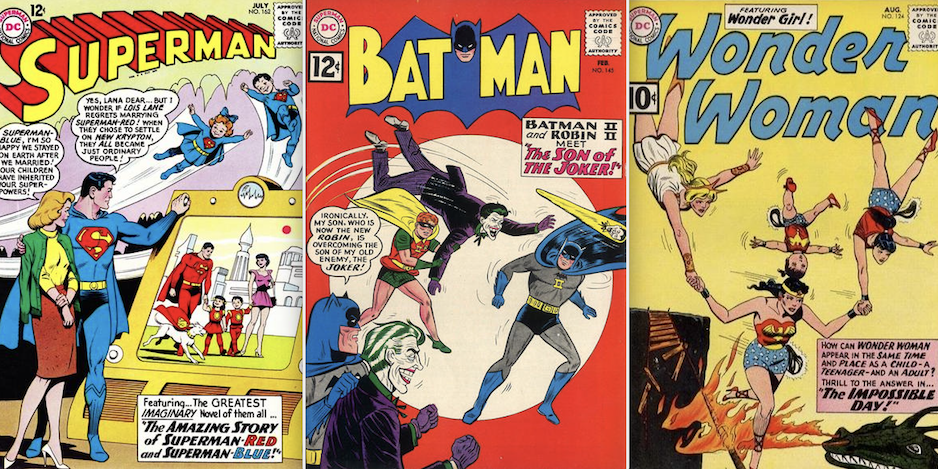

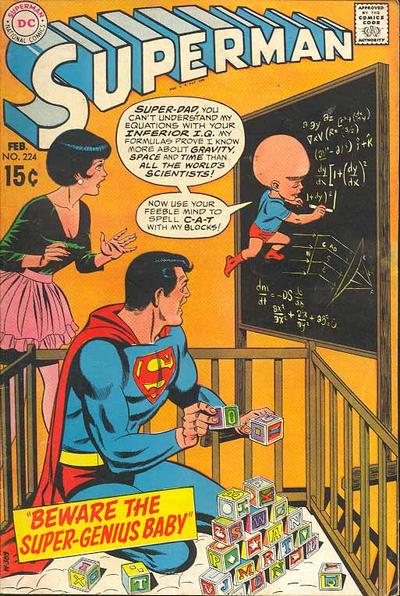

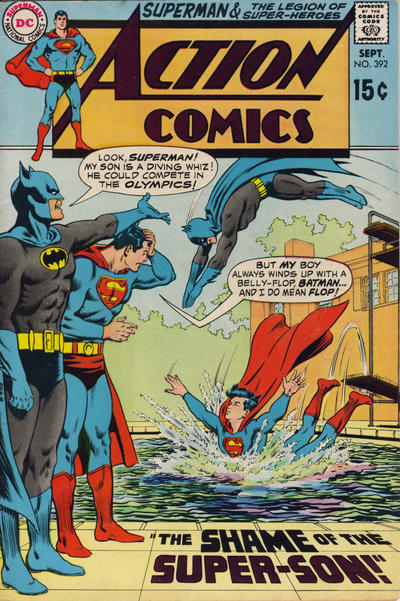

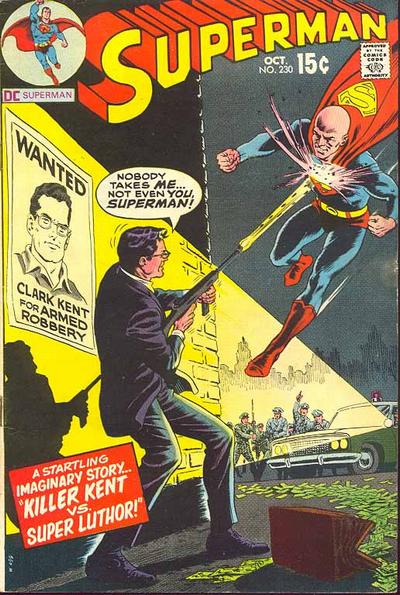

Left: Kurt Schaffenberger. Center: Sheldon Moldoff. Right: Ross Andru pencils, Mike Esposito inks.

By JOHN WELLS

What if Clark Kent and Lois Lane got married? Would the legacy of Batman be carried on by Dick Grayson? How would the world react to the death of Superman? By 1970, all of those questions had been asked and answered—sometimes on multiple occasions—in the pages of DC comic books by way of a concept that editor Mort Weisinger dubbed the “Imaginary Tale.”

The concept of alternate history was not new, even then. In Joanot Martorell’s Tirant lo Blanch (1490), the city of Constantinople did not fall to the Turks as it had in the reality of 1453. French writer Louis Geoffroy imagined Napoleon Bonaparte’s conquest of England in an 1836 tome and Noël Coward’s 1946 play Peace in Our Time posited Nazi occupation of the United Kingdom following victory in the Battle of Britain.

World War II figured into DC’s earliest alternate histories, starting with a two-page fantasy by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in Look Magazine (February 27, 1940) wherein Superman snatched up Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin for judgment by the League of Nations. Once the U.S. had actually joined the war effort, 1942’s Action Comics #52 and Batman #12 each grimly postulated a United States that had fallen to the Nazi scourge.

Meanwhile, Superman tilted toward lighter subject matter in several prototypical “imaginary tales.” Issue #19 (1942), for instance, had Clark Kent dreaming that Lois Lane had discovered his identity in one tale while another had them impossibly attending the then-new theatrical Superman cartoon. A 1943 story transplanted Lois and Clark to the Gay Nineties (Superman #24), while a 1944 episode sent the Man of Steel back in time as a “Stand-In for Hercules” (Superman #28).

—

Curt Swan pencils, Stan Kaye inks

SILVER AGE SUPPOSITIONS

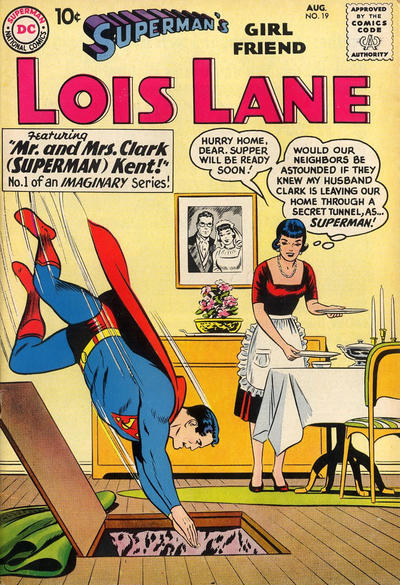

The potential of such out-of-continuity stories wasn’t truly recognized until the late 1950s, when the aforementioned Mort Weisinger launched an all-out campaign to expand and enrich the core details of the Superman series into a bigger, grander mythology. Along with establishing more malleable characters like Supergirl and locales like the Phantom Zone and Kandor, the veteran editor also realized there was nothing to stop him from running stories that completely broke away from its most enduring conventions. Hence, a series of stories where Lois and Clark were husband and wife (beginning in 1960’s Lois Lane #19), carefully identified as an “imaginary series” to preserve the sanctity of the Clark/Lois/Superman triangle in the official Superman continuity.

In 1983’s Amazing Heroes #29, cartoonist and future Image Comics co-founder Jim Valentino penned what still stands as the definitive study of this sub-category. “An imaginary story is any story which alters or in any way repudiates any preexisting continuity,” he wrote, “ergo creating a completely self-enclosed continuity in the process. In no way do the events in an imaginary tale affect or alter existent storylines; they are, in essence, purely speculative—or, if you will, fictitious.

“Imaginary tales can be further sub-divided into four basic categories of definition. The first of these four is the most numerous, and shall be termed ‘actual’ imaginary tales. These are stories which proclaim (usually on both the cover and splash page) that they are imaginary tales and, in fact, comply with the above definition.

Sheldon Moldoff

“‘Inferred’ imaginary tales are those not claiming to be so, yet which correlate to the above definition. ‘Recited’ imaginary tales are stories that use a narrative device to tell the story (such as Superman’s super-computer or Batman’s butler, Alfred). The [former] was used in Superman #132 [in 1959], the first imaginary tale [in the Silver Age revival of the concept]. The final and least common is the ‘false’ imaginary tale. Such stories claim on the cover and/or splash page to be imaginary tales, but do not create their own continuity or fail in any way to depart from pre-established continuity.”

The imaginary tale concept was an immediate hit, one that produced such classics as the tragic “Death of Superman” (1961’s Superman #149) and utopian “Amazing Story of Superman-Red and Superman-Blue” (1963’s Superman #162).

Wonder Woman writer/editor Robert Kanigher countered with a series of “impossible stories” that united the toddler, teenage and adult incarnations of the Amazing Amazon as side-by-side teammates with their mother (1961’s Wonder Woman #124 and others). Meanwhile, Batman editor Jack Schiff dabbled with the concept himself, notably in a recurring run of stories wherein an adult Robin and Bruce Wayne’s son became Batman and Robin II (1960’s Batman #131 and others).

There was an important distinction between the Kanigher and Schiff approaches and the Superman office. The former were less about “What if?” than simply ongoing alternate realities. With rare exceptions, each Weisinger imaginary tale stood on its own, positing a different scenario each time.

—

Curt Swan pencils, Jack Abel inks

WANTED: NEW IMAGINATION FOR IMAGINARY TALES

By the end of the 1960s, though, those scenarios had mostly been played out. The Wonder Family and second Batman and Robin team were long gone and virtually every Superman-related imaginary tale was another variation on a Lois Lane marriage and her offspring.

Such was the case with “Beware the Super-Genius Baby” (Superman #224, on sale in December 1969).

Scripted by Robert Kanigher, the plot involved evil scientist Professor Ulvo bathing a pregnant Lois in a ray that mutated her fetus into a super-genius with an oversized bald head to hold his prodigious brain. At a week old, the ungrateful brat was already lecturing Lois on her poor housekeeping and cooking while taking Superman to task for irresponsible behavior in stopping disasters.

Written as farce, Kanigher’s story would have benefited from the cartoony, expressive stylings of Kurt Schaffenberger, but the former Lois Lane artist was now assigned exclusively to the Supergirl feature in Adventure Comics. Instead, veteran penciller Curt Swan drew the script straight while inker George Roussos gave the finished product a frankly tired look.

Curt Swan pencils, Murphy Anderson inks

Kanigher’s next imaginary tale came off a bit better, illustrated this time by Ross Andru and Mike Esposito (Action Comics #391–392, on sale in June and July 1970). The subject was again Superman’s son, but this version of the character was as inferior to his famous father as the super-genius had been superior. Frustrated by Superboy Jr.’s well-intentioned bungling and Batman’s repeated needling about his own overachieving offspring, Superman finally snapped and used gold kryptonite to permanently remove the 14-year-old’s powers. In the second chapter, remorse set in and the Man of Steel ultimately used Kryptonian science to transfer his powers into Junior… at the expense of his own.

Uncharacteristically for imaginary tales, Kanigher played coy on the identity of Superman’s wife, directing that her face appear only in shadow and that she always wear a blonde wig lest she be assumed to be the dark-haired Lois or red-tressed Lana Lang.

The two-parter also represented the final two issues of Action Comics that Mort Weisinger ever edited. Retiring on April 1, 1970, Weisinger handed off the title to Murray Boltinoff while Julius Schwartz was slated to succeed him on Superman a few months later. Like Action, Weisinger’s run on Superman closed with a two-part imaginary tale in Issues #230 and #231. On sale in August and September 1970, the issues finished their production process in the hands of editorial assistant E. Nelson Bridwell. That explained such details as writer and artist credits on the stories, a rarity in the Weisinger era.

Curt Swan pencils, Murphy Anderson inks

Along with signature Superman writer Cary Bates and penciler Curt Swan, those credits included a fresh name in the form of Dan Adkins. A one-time assistant to the legendary Wally Wood, Adkins brought an inky polish to the two-parter that elevated the production as a whole. The splash page, for one, was an eye-catching composition that included Superman explaining the concept of an imaginary tale atop the Daily Planet globe above an Eisner-esque sculpture of the story’s title: “Killer Kent versus Super Luthor.”

In this reversal on the normal order of things, young Lex-El—bald after exposure to a radioactive mineral—fled to Earth with his father to escape the destruction of Krypton. In this account, Jor-El was actually responsible for the planet’s doom, unleashing an apocalypse because he insanely blamed the planet’s government for the accidental death of his wife Lara. Meanwhile on Earth, Jonathan and Martha Kent were no more respectable. Here, the couple were notorious Bonnie-and-Clyde-type bandits who were on the run from the police when a plummeting rocketship—guess who?—caused a fatal car crash. Inevitably, their son Clark grew up to fight the heroic Superman (a.k.a. Lex Luthor) but came to a tragic end.

At a collective 44 pages, the Super Luthor story was one of the longest imaginary tales to date, but it nonetheless had all the earmarks of a classic Weisinger-edited effort. The plot was packed with ironic parallels and twists that were best appreciated by readers familiar with the Superman mythology.

—

MORE

— BEFORE THE IMPLOSION: The Rise of DC’s DOLLAR COMICS

— 13 COVERS: A Marvel WHAT IF? Extravaganza

—

Back Issue #111 is due March 13. You can get it through your comics shop or directly from publisher TwoMorrows.

March 3, 2019

Well, imagine that. ^_^

March 4, 2019

Interestingly enough, many of the Wonder Family stories were NOT labeled “impossible” or had non-impossible introductions that were clearly false, such as Diana introducing a story of herself as a teenager, when that story showed her and Donna side by side. I think the series is enriched if we add the non-labeled stories to the mythos. I mean, there are some completely charming stories in there! I know that as a child I was captivated by the amazing Wonder Family. I also place Donna Troy’s first appearance as WW123, the point at which she forever after was treated as a separate character from Diana. It’s not her fault that various staffs were so uninterested in the Wonderverse that they didn’t realize what had been done.