The documentary filmmaker who’s chronicled Grant Morrison, among many comics heavyweights, is now shooting a film on Neil Gaiman. He weighs in on The Sandman Overture and Gaiman’s approach to storytelling.

I’m currently working on a documentary about Neil Gaiman. I spent two weeks on the road filming material during Neil’s UK signing tour earlier this year, and have been editing that material since, and reading a lot of Gaiman writing as well. So, I was primed and ready to check out his new Sandman series, Overture.

Partially due to his general shift to prose, more than any other writer in comics, a new Neil Gaiman book feels like an event. When most big-name writers are doing three or four titles a month, Neil is doing a miniseries every two or three years. It’s legitimately exciting to have him back in comics, and the thought that in a year or so we could have not only new Sandman, but also new Miracleman/Marvelman, is a cause for real excitement. And, a large part of what’s exciting is that Neil’s approach to writing comics is so different from virtually everyone else out there.

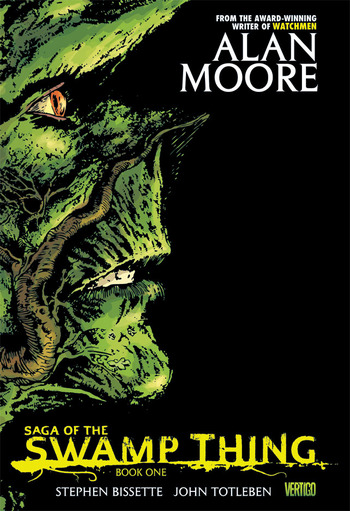

Most comics writers of the past 10 to 20 years have drawn their primary influence from cinema. In popular and influential books like The Authority or The Ultimates, the dominant method for designing the page is widescreen panels that mimic a movie screen. Thought balloons are almost non-existent and captions are used primarily for quick scene-setting, not extended narration. This new style was pioneered by Alan Moore in his influential ’80s works like V for Vendetta. Thought balloons can be goofy, and many ’60s and ’70s comics are so saturated in captions, you can barely read them, but to follow this one strain of Moore is to ignore his lyrical writing in Swamp Thing and Miracleman, where he used captions and narration to immerse the reader deeply in the story.

Sandman draws some of its characters, and its general storytelling style, from Moore’s Swamp Thing. But, it adds an emphasis on Gaiman’s love of story and storytelling. During his book tour, Gaiman read chapters from his books to an enraptured audience, and looking at this comic, you get that same sense of a master storyteller sitting down to spin a yarn for you.

Just compare the amount of text on any given page to that of a typical comic. Gaiman’s not afraid to sit back and tell you a story, and I find that very refreshing. Comics can do so much, but people often seem locked into this one specific style, a decompressed style that often results in comics that take about five minutes to read, and leave you with very little to chew over.

Reading Sandman the first time, what impressed me so much was the sheer amount of stories. There was the overall story of Dream and numerous smaller arcs within the series. Nothing out of the norm there. But within those arcs were standalone stories with fully developed worlds, many of which feature characters telling stories within those stories. This issue features a brief meditation on George Porticullis’ dreams, as well as the evocative opening on a plant universe. And, in each case, Gaiman uses just enough prose to get his points across, and lets the art handle the rest.

And that art, by JH Williams III, is amazing. I consider Williams not only the best comics artist working today, but the best ever in the medium. His ability to move between styles and experiment with page layout is unprecedented in the medium, and every single page both tells a story and is an amazing standalone work of art on its own merits.

To some extent, Overture suffers from the prequel problem of providing small interesting moments, but not the suspense of wondering where the story will go. But, the closing foldout splash page indicates some new territory to explore, and the promise of more small stories set in this world means that even if we know where the overall story is going, there’re going to be plenty of digressions to enjoy along the way.

Patrick Meaney, the co-founder and president of Respect! Films, has most recently completed docs on Warren Ellis and the Image Comics revolution of the ’90s. He’ll be stopping in here from time to time.