A birthday tribute to Stanley Kubrick…

—

UPDATED 7/26/23: The late Stanley Kubrick was born 95 years ago. Perfect time to re-present this piece from Jack Kirby’s centennial celebration in 2017. Dig it. — Dan

—

Rob Kelly’s REEL RETRO CINEMA offers new looks at old flicks — and their comic-book adaptations. Here, he takes on 2001: A Space Odyssey as part of our 13 DAYS OF KIRBY 100 celebration of the King’s centennial. For other REEL RETRO CINEMA columns, click here. or the complete 13 DAYS OF KIRBY 100 Index of stories and features, including essays by the likes of Alex Ross, John Byrne, Marie Severin, Kelley Jones and many others, click here.

By ROB KELLY

In 1968, Stanley Kubrick decided to slow things down.

As a new wave of directors and writers descended on Hollywood in the late 1960s, movies got faster and faster. Just a year earlier, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde ushered in a new level of hyped-up screen violence, and the film became a massive, groundbreaking hit.

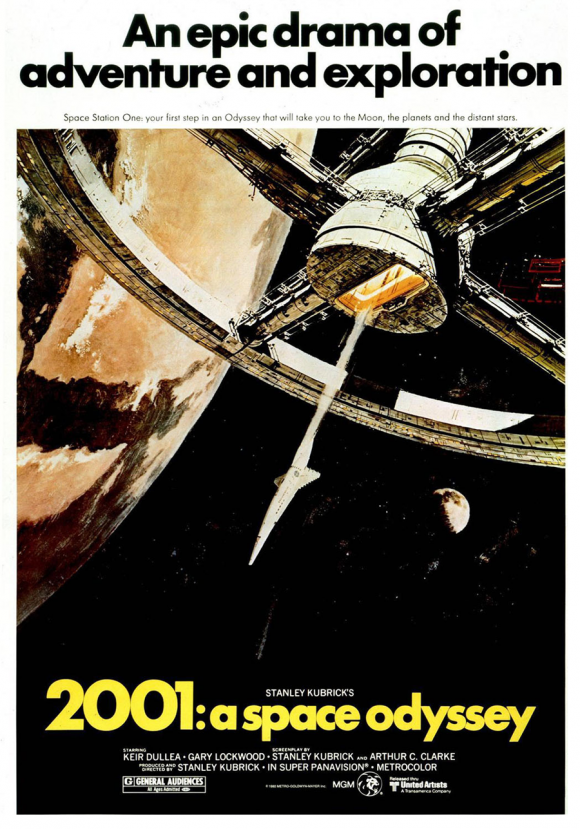

But Stanley Kubrick was never one for rushing. It had been a full four years since his last film, Dr. Strangelove, and when he returned to movie theaters it was with a film of breathtaking visuals and challenging ideas.

Loosely based on a short story of Arthur C. Clarke’s called The Sentinel, 2001: A Space Odyssey would open in our prehistoric past, focusing on a small tribe of hominids as they struggle to survive. Featuring no music and no dialogue, Kubrick was testing audiences’ patience and forcing them to accept the rhythms from the distant past he was trying to replicate. Eventually, however, something strange happens: A solid black monolith appears, which seems to guide the hominids into learning how to use bones as a weapon. One of them, in an orgiastic display of enlightenment, tosses a bone into the sky. We then make a flash cut to a space station orbiting Earth, a time jump of several hundred million years.

In its slow, methodical way, 2001 reveals its story. Another monolith, similar to the one that appeared in our prehistoric past, has been discovered on the moon. When a team of astronauts investigates, it emits a powerful high-pitched signal. We then jump another 18 months ahead, and two astronauts, Drs. David Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) are on a mission in deep space.

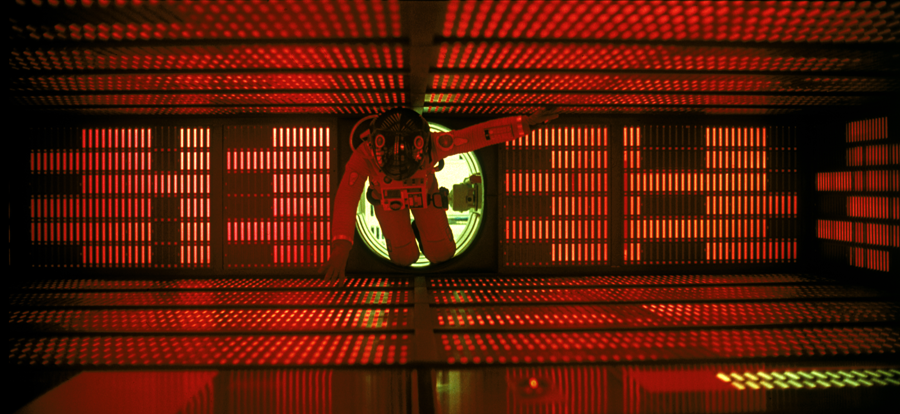

Controlling the higher functions of the ship is the computer system known as HAL, which is “foolproof and incapable of error.” It doesn’t take long for us to see how untrue that is, because eventually HAL decides that the mission is in danger, and kills Dr. Poole, and attempts to kill Bowman. Bowman manages to deactivate HAL, and then learns the true directive of the mission: to investigate a third monolith that has been discovered orbiting Jupiter.

Bowman’s ship is then pulled into a bewildering vortex of colored light, seemingly depositing him light years away. He awakens in a bedroom, decorated in a style humans would be familiar with. He soon sees what looks to be an older version of himself, and another monolith appears. When he reaches out to touch it, he is transformed into a fetus bathed in an orb of light. The fetus orbits Earth, gazing at it, as the film ends.

Film historians have been arguing for decades what Kubrick was trying to get at with 2001: A Space Odyssey. Indeed, even Arthur C. Clarke himself has expressed some bewilderment at what Kubrick did with his original story. Having seen the film multiple times now, the story seems remarkably straightforward: Intelligent life from outer space has been watching Earth, and every so often has been sending us these monoliths as a sort of outer-space version of a highway sign; they’re pointing us in a direction we need to go.

What’s so remarkable is the style that Kubrick employs in telling the story: Unconcerned with how fast movies were getting, he lets scenes play out at a pace that might, on first blush, seem boring, but achieve a real-world verisimilitude that makes 2001 feel almost like a documentary that just happens to take place in the future. Of all the science-fiction films I have seen, 2001: A Space Odyssey feels, to me, like the closest to what Earth’s future will actually be like.

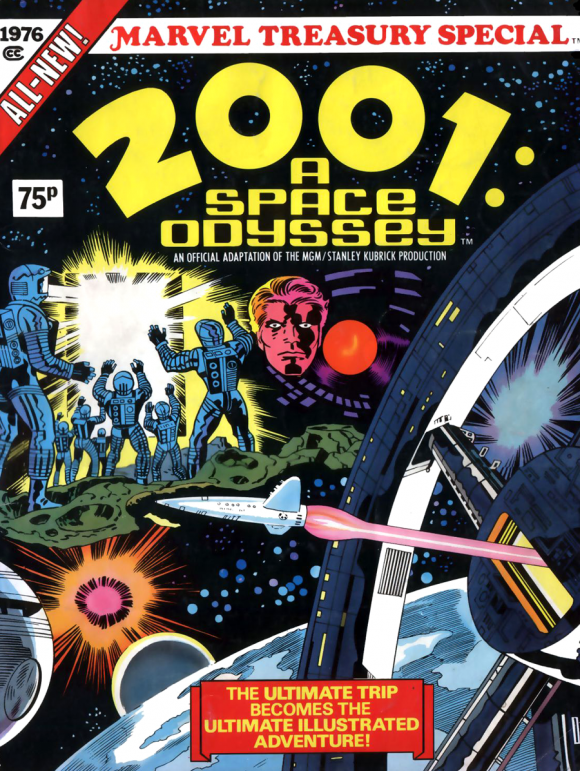

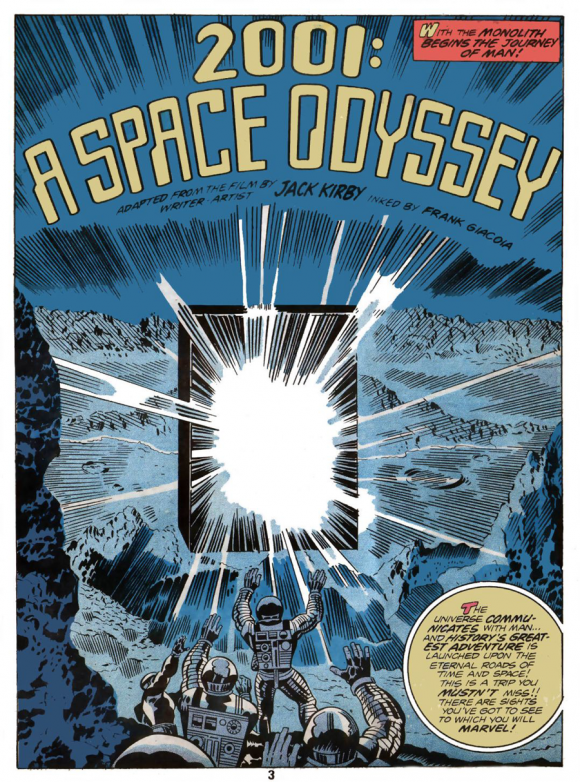

The esteem for 2001 only grew over time, and it didn’t take long for the general consensus to form that the film was a masterpiece. So you could imagine that, when Marvel Comics chose to adapt the movie into comic-book form in 1976, most comic-book creators would be pretty intimidated about taking it on. But Jack Kirby wasn’t easily—if ever—intimidated, so he was tasked with the job, the results of which were published as a treasury-sized comic, under the title Marvel Treasury Special.

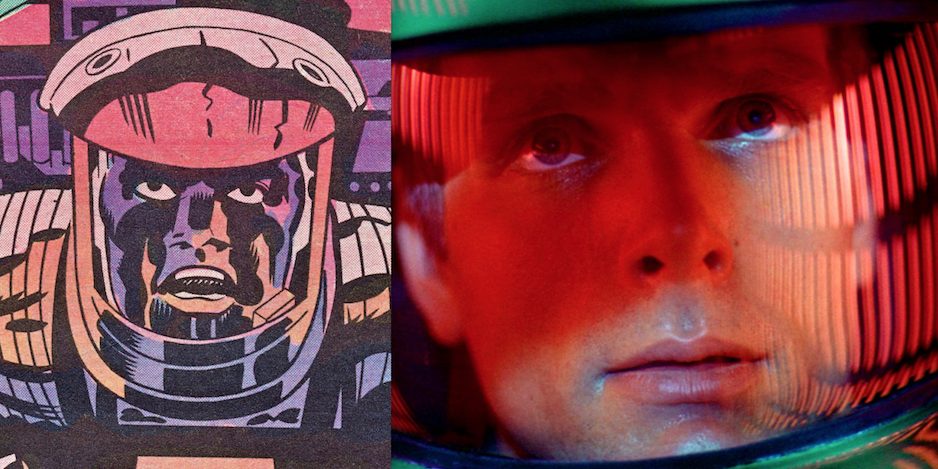

Kirby, whose work was not known for its quiet reserve, seems like an odd choice to adapt the work of Stanley Kubrick (what is it with teaming Kirby with people named Stanley?). In 2001: A Space Odyssey the comic, all of the themes that Kubrick left unspoken become spoken, with third-person narration explaining to us just what is happening. The book opens like the film, with an extended visit to prehistoric times. Eschewing Kubrick’s visuals, Kirby establishes his own particular POV, replicating the film’s most memorable sequences in his own inimitable way.

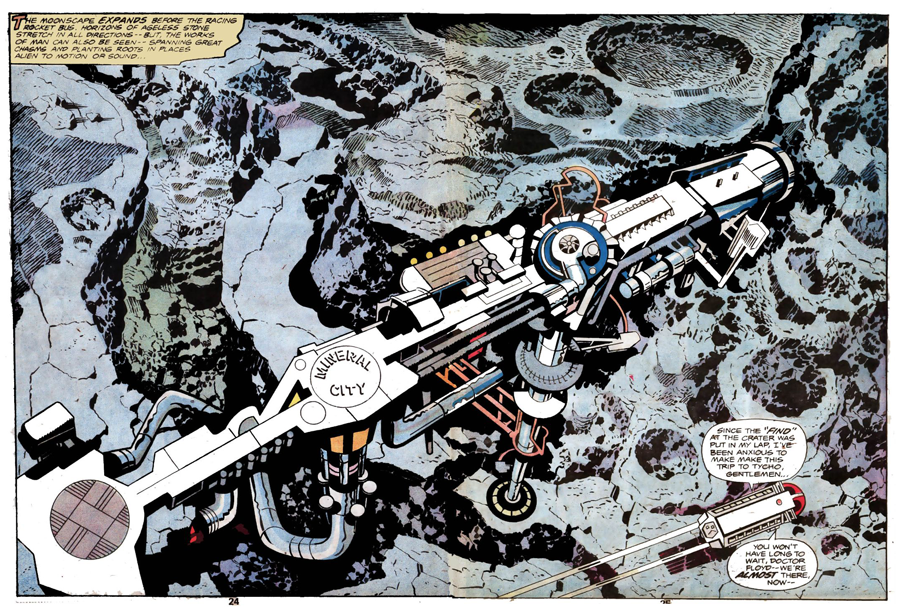

He also works in some of the futuristic collages he was experimenting with earlier in his career—Part 2 of the book (“The Thing on the Moon!”) is suitably jarring, as all of a sudden we’re met with quiet grays and right angles. Kirby, of course, was a master at visualizing impossibly complex machinery, and he achieves that here, as well. Bowman and Poole are leads right out of Kirby Central Casting—muscular, lantern-jawed Men of Action, so when HAL turns on them it’s unsettling. We’re not used to seeing Kirby heroes so outmatched like this. He lets it rip during the film’s final “Star Gate” sequence, filling the extra-large pages with swirls of color mixed with healthy doses of that trademark Kirby Krackle.

Does 2001: A Space Odyssey “work” as a comic book? Depends on how you look at it (literally). As a printed adaptation of Stanley Kubrick’s trippy exploration of deep space, you’d probably say no. Kubrick was such a master at combining visuals with sound that his films use every tool available to create a singular cinematic event. The man only directed a handful of movies in his five-decade career, but they are all distinctive and unlike anything else that had come before (and, in some cases, since). All of the subtlety that makes 2001 so mysteriously engaging is gone, replaced by bright colors and bombast.

Yet, I can’t dismiss Kirby’s version. Jack Kirby was no less a genius than Kubrick, and his comics didn’t look like anything else that had come before. Kirby doesn’t so much adapt Kubrick as he does transform it, and filter it through his unique artistic vision. While Kirby didn’t have the audio component Kubrick had to work with, he did have the opportunity that Kubrick didn’t have: to change the size of the frame. All of Kubrick’s beautiful imagery had to fit in the dimensions of a movie screen, while Kirby could—and did—change it up as the plot saw fit: Some panels are tiny and cramped, others are tall and narrow, and still others are double-page spreads which, when done as a treasury comic, immerses the reader into the world of deep space.

I’ve read the 2001: A Space Odyssey comic several times now and there’s just something about it that keeps me coming back to it. It’s a rare example of Kirby getting to do work at Marvel that wasn’t concerned with being part of a larger comic-book universe, so the world on display here is entirely his. This book isn’t Jack Kirby’s Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s simply Jack Kirby’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Kirby continued to play in this world when 2001: A Space Odyssey was turned into a regular series. In its 10 issues, Kirby would leave any vestiges of Kubrick and Clarke behind, completely transforming the world of the monoliths and Star Children into something that was uniquely (and often bizarrely) his. Once again not having to concern himself (yet) with a larger comic-book continuity, in some ways the 2001 regular series is Kirby at his most pure, throwing out ideas right and left and daring the reader to try and keep up, not unlike Stanley Kubrick.

While no one would put 2001: A Space Odyssey on a list of Kirby’s best, it offers the rare example of the King of Comics adapting the work of someone else at his level in terms of creative genius. The 2001 treasury comic is a trip worth taking, and you don’t even need a space suit.

—

MORE

— The Complete 13 DAYS OF KIRBY 100 Index of Stories and Features. Click here.

— The TOP 13 Issues of JACK KIRBY’s 1970s Return to MARVEL — RANKED. Click here.

—

Rob Kelly is a writer/artist/comics and film historian. He is the co-host of Aquaman and Firestorm: The Fire and Water Podcast, the host of The Film and Water Podcast, and the host of TreasuryCast. He can’t read lips.

July 30, 2021

I love reading this kind of love and passion for comic books!

July 28, 2023

I’ve always loved Aaron Stack’s odyssey through the Marvel Universe that concluded in X-51 #12 with the return of the monolith and a choice.

It was a satisfying full circle moment.

July 29, 2023

I love Jack’s 2001 series. It’s one of my favorites of his 70s works, there’s some great work from him there.